Legal Malpractice in Texas Third Edition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

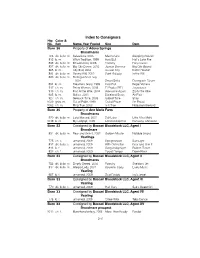

To Consignors Hip Color & No

Index to Consignors Hip Color & No. Sex Name,Year Foaled Sire Dam Barn 36 Property of Adena Springs Broodmares 735 dk. b./br. m. Salvadoria, 2005 Macho Uno Skipping Around 813 b. m. Witch Tradition, 1999 Holy Bull Hall's Lake Fire 833 dk. b./br. m. Beautiful Sky, 2003 Forestry Forty Carats 837 dk. b./br. m. Big City Danse, 2002 Joyeux Danseur Big City Bound 865 b. m. City Bird, 2004 Carson City Eishin Houlton 886 dk. b./br. m. Devine Will, 2002 Saint Ballado In the Will 889 dk. b./br. m. Distinguished Lady, 2004 Smart Strike Distinguish Forum 894 b. m. Dreamers Glory, 1999 Holy Bull Regal Victress 917 ch. m. Feisty Woman, 2003 El Prado (IRE) Joustabout 919 ch. m. First At the Wire, 2004 Awesome Again Zip to the Wire 925 b. m. Galica, 2001 Dixieland Brass Air Flair 927 ch. m. Getback Time, 2003 Gilded Time Shay 1029 gr/ro. m. Out of Pride, 1999 Out of Place I'm Proud 1062 ch. m. Ring True, 2003 Is It True Notjustanotherbird Barn 35 Property of Ann Marie Farm Broodmares 970 dk. b./br. m. Lake Merced, 2001 Salt Lake Little Miss Molly 1019 b. m. My Lollipop, 2005 Lemon Drop Kid Runaway Cherokee Barn 33 Consigned by Baccari Bloodstock LLC, Agent I Broodmare 831 dk. b./br. m. Bear and Grin It, 2002 Golden Missile Notable Sword Yearlings 775 ch. c. unnamed, 2009 Speightstown Surf Light 832 dk. b./br. c. unnamed, 2009 With Distinction Bear and Grin It 846 b. f. unnamed, 2009 Songandaprayer Broken Flower 892 ch. -

22 February Playlist

89.1 WBSD FM 400 McCanna Parkway, Burlington, WI 53105 Current Playlist: 22 February, 2021 General Manager: Thomas Gilding, email [email protected] Music Director: Heather Gilding, email [email protected] WBSD is not taking music calls at this time. Email the GM and he will get back to you. Added This Week Barry Gibb Greenfields: The Gibb Brothers Songbook, Vol. 1/Butterfly Capitol Barry Gibb Greenfields: The Gibb Brothers Songbook, Vol. 1/Run To Me Capitol Barry Gibb Greenfields: The Gibb Brothers Songbook, Vol. 1/To Love Somebody Capitol Alpha Cat Pearl Harbor 2020/Once Upon A Time Independent Langhorne Slim Strawberry Mansion/Dreams Dualtone Bruce Sudano Spirals Vol. 2…Time the Space In Between/It Don’t Take Much(Because I Do) Independent Dropped This Week Aliensdontringdoorbells Arrival/Story Independent Roan Yellowthorn Rediscovered/We Just Disagree Blue Elan Last Bees featuring Ian Ash single/Earlier Grave Independent Jesse Malin Lust for Love/Todd Youth Wicked Cool Pineapple Thief Versions of the Truth/Demons Independent Mike Edel En Masse/Good About Everything Independent Spins this Past Week 1 25 Stephen Kellogg 2021/I’ve Had Enough Independent 2 24 Juni Ata Saudade/Not Going Anywhere Independent 3 23 Andrew Cassara Freak On Repeat/Bad Bad Independent 3 23 Nude Party Midnight Manor/Cities New West 5 22 Travis 10 Songs/The Only Thing BMG 5 22 Gorillaz Song Machine/The Valley of the Pagans Parlophone/Warner 5 22 Taylor Swift Folklore/August Republic 8 21 Guided By Voices Styles We Paid For/Megaphone Riley Independent 8 21 Smashing -

Das Runde Muss Ins Eckige

Monatszeitschrift für Luzern und die Zentralschweiz mit Kulturkalender NO. 7 Juli /August 2011 CHF 7.50 www.null41.ch LUZERN HAT EIN NEUES STADION ECKIGE INS MUSS RUNDE DAS SEITE 6 DAS ABO- e: Daniela Kienzler / Fotografi tbs-identity.ch GEFÜHL. Zum Beispiel mit unserem TANZ-ABO. Seien Sie besonders LUZERNER günstig dabei, wenn Bewegung auf die Bühne kommt: Mit zwei Tanzpremieren und je einer Vorstellung im UG und im Südpol. THEATER... www.luzernertheater.ch 2 Neue Website! LuTh_Kuma_Abo_201112.indd 1 14.06.11 12:15 EDITORIAL SCHNABEL AUFREISSEN «Wo sind denn all jene, die sind glücklich über den Na- sonst immer den Schnabel turrasen und hoffnungsfroh aufreissen?», fragt Walti be- angesichts des zweiten Ya- rechtigterweise unter www. kin beim FCL. Doch auch kulturagenda2020.ch. Auf Befürchtungen über zu viel der Plattform der IG Kultur Lifestyle auf der Allmend kann man seit Mai loswer- und generell einen Graben den, was man zur Luzerner zwischen Clubführung und Kultur schon immer sagen Fans sind unüberhörbar. wollte – ob motzen oder Kreativ umgestaltete FCL- konstruktive Vorschläge, al- Werbeplakate zeugten da- les ist erlaubt, und gute Ide- von («Football is Life, not Manuel Sanmartin, Spanien, 63. Nicht fussballinteressiert. en fliessen vielleicht in die Lifestyle!»). Arbeit am neuen Kulturstandortbericht ein. Die Eröffnung des Stadions war für uns Anlass für Nie war es einfacher, seine Meinung am richtigen eine Porträtserie über die wahren Helden des neu- Ort loszuwerden. Umso erstaunlicher also, wie en Tempels: die Arbeiter, die ihn gebaut haben. Die wenig auf der Website derzeit passiert. Die einzige Bilder von Marco Sieber entstanden spontan und wirkliche Debatte drehte sich um das Niveau der unverfälscht auf der Baustelle. -

The Next Akron' 14-35 'The Akron We Know' As Told by 34 Different People 17 How to Know When You've Hit Rock Bottom 24-29 a Shopper's Guide to Akron Made Awesome

DECEMBER 2016 • VOL 2 • ISSUE #12 • THEDEVILSTRIP.COM 10 Where to find 'The Next Akron' 14-35 'The Akron We Know' as told by 34 different people 17 How to know when you've hit rock bottom 24-29 A Shopper's Guide to Akron Made Awesome FREE A PROGRAM OF FOUNDING PARTNERS SUPPORTED BY More than 40 experiences Huntington Bank fireworks at 9 p.m. and midnight Free parking and METRO shuttles New attractions Wesley Bright & the Honeytones at the Akron Civic Theatre Jul Big Green on the Mill Street Main Stage The Chardon Polka Band at the JSK Center Learn a little about a lot from eight inspirational Akronites at PechaKucha Saturday, December 31 Returning crowd favorites Silent Disco is back and bigger from 6 p.m.-midnight than ever Dance the night away at Admission $ Greystone Hall with Akron Big Band buttons available for 10 Bundle up and enjoy horse drawn at Acme Fresh Market, sleigh rides on Main Street FirstMerit Bank branches and Goodyear Ice Sculpture Garden with carving demos and firstnightakron.org special appearances Follow us on #firstnightakron17 Discover Downtown Akron Passports also available for $15 and include admission to PLATINUMFirst Night PARTNERSAkron 2017. table of contents table of 18 contents 14 THE ARTS 13 Author Corey Sheldon gives us a peek into the Valley of Progress 14 Humans of Akron know art. The Devil Strip 12 E. Exchange Street 2nd Floor CULTURE CLUB Akron, Ohio 44308 17 Humans of Akron recover, too. Publisher: Chris “no carny-handed mango man” Horne Email: [email protected] 18 Humans of Akron have culture Phone: 330-555-GHOSTBUSTERS 13 22 Art Director: Alesa “doesn’t sleep” Upholzer Managing Editor: ENTREPRENEURSHIP M. -

APRIL 29, 2005 Political Leaders Speak at Martinsville Campus PC VIRUS RAVAGES Politics

THE NATION'S OLDEST NOW ON THE WEB! COUNTRY DAY SCHOOL http://record.pingry.org NEWSPAPER VOLUME CXXXI, NUMBER 4 The Pingry School, Martinsville, New Jersey APRIL 29, 2005 Political Leaders Speak at Martinsville Campus PC VIRUS RAVAGES politics. Max Cooper (V) asked both parties. By CAROLINE SAVELLO (VI) know why you want to get into of his visits are to the districtʼs the former governor what it was Despite her conservative po- politics. Understand the issues public schools. In fact, Rep. Frel- SCHOOL COMPUTERS with like to be interviewed by Ali G, litical leanings, Ms. Whitmanʼs DARINA SHTRAKHMAN (III) that you care about and find inghuysen says he visits about 90 a satirical character created by message of forward-thinking out about local campaigns. Get schools in the area each year, in It has hardly been “politics comedian Sacha Cohen Brown. politics and the countryʼs future to know people; let them get to addition to local universities such OVER SPRING BREAK as usual” at Pingry over the past According to the showʼs official appealed to the common political know you. Make sure youʼre part as Fairleigh-Dickinson, Drew, month. A succession of national website, Ms. Whitman chatted ground among students rather of the discussion.” and Rutgers. By MELISSA LOEWINGER (IV) with Brown about “solar energy than their partisan interests. Ms. Congressman Rodney Frel- politicians and guest lecturers has The 20 seniors enrolled in the The W32.Mytob@mm vi- Whitman said that her new book, inghuysen, the Republican rep- brought citizen action and public AP Government class discussed rus entered and infected the policy issues to the forefront of “Itʼs My Party, Too: The Battle resentative of the 11th District of government and public policy for the Heart of the GOP and the schoolʼs entire computer sys- assemblies and classes. -

Song Machine

UNDER EMBARGO UNTIL 9.00AM (UK TIME) – FRIDAY 23 OCTOBER 2020 SONG MACHINE NEW ALBUM – OUT NOW LIVE DATES ANNOUNCED LIVE CHAT TODAY TUNE IN HERE “…a fluent, brilliant whole.” – 4/5 stars – THE GUARDIAN “Song Machine... is the most cohesive Gorillaz album since Demon Dayz... sparkling with energy and invention…” – 4/5 stars – MOJO UNDER EMBARGO UNTIL 9.00AM (UK TIME) – FRIDAY 23 OCTOBER 2020 23rd October 2020: Song Machine: Season One - Strange Timez – the highly-anticipated new album from Gorillaz has finally arrived! LISTEN HERE. With seven episodes available to date, each with its very own video following the adventures of Noodle, 2D, Murdoc and Russel in the studio and across the world, the complete Season One collection is available now for the first time. Today also sees the biggest virtual band in the world announce a string of live shows, with a global live streaming performance in December and a run of dates next year. The SONG MACHINE TOUR will see Gorillaz broadcast their first show since 2018 live on 12th and 13th December, ahead of a visit to Köln, Berlin and Luxembourg next summer, with a homecoming show at The O2, London on 11th August 2021. Ticket info here. Finally, tune in later today to join Damon Albarn, Remi Kabaka and a selection of the featured artists who appear on Song Machine for a live chat at 1700 BST, Friday 23rd October. WATCH HERE. SONG MACHINE LIVE on 12th and 13th December (2020) is Gorillaz’ first live performance since 2018 and will be broadcast live around the world with three separate shows taking place across three time zones through the magic of LIVENow. -

Table of Contents Pagan Songs and Chants Listed Alphabetically By

Vella Rose’s Pagan Song Book August 2014 Edition This is collection of songs and chants has been created for educational purposes for pagan communities. I did my best to include the name of the artists who created the music and where the songs have been recorded (please forgive me for any errors). This is a work in progress, started over 12 years ago, a labor of love, that has no end. There are and have been many wonderful artists who have created music for our community. Please honor them by acknowledging them if you include their songs in your rituals or song circles. Many of the songs are available on the web, some additional resources are included in Appendix A to help you find them. Blessings and thanks to all. NOTE: Page numbers only works to 170 – then something went wrong and I can’t figure it out, sorry. Table of Contents Pagan Songs and Chants Listed Alphabetically By Title p. 2 - 160 Appendix A – Additional Resources p. 161 Appendix B – Song lists from select albums p. 163 Appendix C – Songs and Chants for Moons and Sabbats Appendix D – Songs and Chants for Winter and Yule Appendix E – Songs for Goddesses Index – Alphabetical listings by First Lines (verses and chorus) 1 Vella Rose’s Pagan Song Book August 2014 Alphabetical Listing of Songs by Title A Circle is Cast By Anna Dempska, Recorded on “A Circle is Cast” by Libana (1988). A circle is cast, again, and again, and again, and again. (repeats) ***** ***** ***** ***** ***** ***** ***** ***** ***** ***** ***** ***** ***** ***** ***** ***** Air Flies to the Fire Recorded on “Good Where We Been” by Shemmaho. -

Rock Album Discography Last Up-Date: September 27Th, 2021

Rock Album Discography Last up-date: September 27th, 2021 Rock Album Discography “Music was my first love, and it will be my last” was the first line of the virteous song “Music” on the album “Rebel”, which was produced by Alan Parson, sung by John Miles, and released I n 1976. From my point of view, there is no other citation, which more properly expresses the emotional impact of music to human beings. People come and go, but music remains forever, since acoustic waves are not bound to matter like monuments, paintings, or sculptures. In contrast, music as sound in general is transmitted by matter vibrations and can be reproduced independent of space and time. In this way, music is able to connect humans from the earliest high cultures to people of our present societies all over the world. Music is indeed a universal language and likely not restricted to our planetary society. The importance of music to the human society is also underlined by the Voyager mission: Both Voyager spacecrafts, which were launched at August 20th and September 05th, 1977, are bound for the stars, now, after their visits to the outer planets of our solar system (mission status: https://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/mission/status/). They carry a gold- plated copper phonograph record, which comprises 90 minutes of music selected from all cultures next to sounds, spoken messages, and images from our planet Earth. There is rather little hope that any extraterrestrial form of life will ever come along the Voyager spacecrafts. But if this is yet going to happen they are likely able to understand the sound of music from these records at least. -

Download/Cp282.Pdf 25 Xxi the Words of Dr

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Beer, Blood, and the Bible: Economics, Politics, and Geolinguistic Praxis in Kongo-Ngola (Congo-Angola) Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/15b4x1sj Author Davis IV, Edward C Publication Date 2018 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Beer, Blood & the Bible: Economics, Politics & Geolinguistic Praxis in Kongo-Ngola (Congo-Angola) By Edward C. Davis IV A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in African American Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Sam Mchombo, Chair Professor G. Ugo Nwokeji Professor Laura Nader Spring 2018 Beer, Blood & the Bible: Economics, Politics & Geolinguistic Praxis in Kongo-Ngola (Congo-Angola) © 2018 Edward C. Davis IV ALL RIGHTS RESERVED 1 Abstract Beer, Blood & the Bible: Economics, Politics & Geolinguistic Praxis in Kongo-Ngola (Congo-Angola) by Edward C. Davis IV Doctor of Philosophy in African American Studies Professor Sam Mchombo, Chair This dissertation argues that educational praxis rooted in local epistemologies can combat the erosion of ethno-histories and provide quotidian securities for quality, tranquil lives free of war and exploitative practices of extraction and overuse of the land for non-subsistence purposes, which deny basic human life to those on the ground. Colonial ethnocide, linguicide, and epistemicide serve as the central focus of this study, which uses mixed anthropological methods to investigate economic production, political history, and cultural transmission, with the goal of advancing language revitalization efforts concerning native epistemologies within the multidisciplinary fields of Africana, African, Black, African American, and African diaspora studies. -

The Bard Observer

OBSERVER: ISSUE 5, VOLUME 19. APRIL 19, 2005 IN THIS ISSUE: - A Look Into Bard Counseling Services. Page2. - C~lumbia Controversy: Key Participants · Speak Out. Page 4. - Free Speech, The SJB and Bard College. Page 14. THE BARD OBSERVER April 19th, 2005 11i4't'ti CONCERNS OVER COUNSELING SERVICES: Bard's Emergency Psychiatric Evaluation Policy BY MICHAEL BE HABIB Rumors abound about the procedures in place had just woken up, that was one of my more patient, it's out-patient, can't you just bill as if it pot, I hate drugs, and they refused to answer ro help and protect Bard students with mental sarcastic days." Repeated questions from the were a consultation,' and no, they can't," she when I asked 'What are you testing me for?' • illnesses or instabilities. According ro the counselor about hearing voices resulted in says. Ms. Stawinski also says that Bard would The four other students also report that the received wisdom regarding treatment of mental Jordan caustically responding, "I hear you so I like its provider to cover in-patient mental hospital was not forthc ming in revealing the health issues at Bard, rhe college's procedures guess I'm not deaf." In response to the stock health care bur that would increase their premi nature of their blood rests. are necessary, benevolent, and up-to-date. questions about eating and sleeping Jordan says ums and higher premiums for the college would According to Jordan and her mother However, several students have shared griev she factually explained that she has a pituitary mean higher tuition for students. -

Id40 2020 Kw 50

ID40 REDAKTION Hofweg 61a · D-22085 Hamburg T 040 - 369 059 0 WEEK 50 [email protected] · www.trendcharts.de 03.12.2020 Approved for publication on Tuesday, 08.12.2020 THIS LAST WEEKS IN PEAK WEEK WEEK CHARTS ARTIST TITLE LABEL/DISTRIBUTOR POSITION 01 01 06 Maximo Park Baby, Sleep Prolifica/[PIAS] Cooperative/[PIAS]/Rough Trade 01 02 04 07 Tocadisco In Love With An Alien Toca45/Zebralution 02 03 05 06 Django Django Spirals (MGMT Remix) Because/Caroline/Universal 03 04 02 09 Idles War Partisan/[PIAS]/Rough Trade 01 05 10 07 Roosevelt Feels Right Greco Roman/City Slang/Rough Trade 03 06 NEW Tocadisco Herz Explodiert Toca45/Zebralution 06 07 07 05 Gorillaz Ft. Beck The Valley Of The Pagans Parlophone UK/WMI/Warner 03 08 17 10 The Smashing Pumpkins Cyr Sumerian/ADA 02 09 06 10 Deftones Genesis Reprise/WMI/Warner 04 10 03 06 King Gizzard & The Lizard Wizard Automation KGLW/Caroline/Universal 03 11 08 02 Royal Blood Trouble's Coming Black Mammoth/Warner UK/WMI/Warner 08 12 12 08 The Medicine Dolls Danger! Danger! Disco! Just Music 11 13 11 04 Jake Bugg All I Need RCA/Sony 07 14 22 04 Sleaford Mods Ft. Billy Nomates Mork N Mindy Rough Trade Records/Beggars Group/375 Media 14 15 13 08 Romy Lifetime Young Turks/Beggars Group/Rough Trade 08 16 26 02 > Architects Animals Epitaph/375 Media 16 17 14 09 Fotos Das Verlangen [PIAS] Recordings/[PIAS]/Rough Trade 14 18 15 07 AC/DC Shot In The Dark Columbia/Sony 11 19 21 03 Soft Kill Pretty Face Cercle Social 19 20 19 05 The Screenshots Manchmal Musikbetrieb R.O.C.K./The Orchard 19 21 09 05 Psychedelic -

1 February Playlist

89.1 WBSD FM 400 McCanna Parkway, Burlington, WI 53105 Current Playlist: 1 February, 2021 General Manager: Thomas Gilding, email [email protected] Music Director: Heather Gilding, email [email protected] WBSD is not taking music calls at this time. Email the GM and he will get back to you. Added This Week Kurt Vile Speed, Sound, Lonely KV/Speed of the Sound of Loneliness Matador Paul Boddy & Slidewinder Blues Band Friends of Tuesday/Makin’ Me Cry Independent Cat Ridgeway Nice to Meet You/Giving You Up Independent Hold Steady Open Door Policy/Family Farm Independent/Thirty Tigers Hiss Golden Messenger Single/Sanctuary Merge Diane Warren The Cave Sessions Vol. 1/Times Like This BMG Dropped This Week Mihali Breathe and Let Go/Over Land and Sea Independent Avett Brothers The Third Gleam/Back Into the Light Independent Alanis Morissette Such Pretty Forks in the Road/Ablaze Independent/Thirty Tigers Juni Ata Saudad/I’ll Try Anything Twice Independent Screaming Orphans Sunshine and Moss/Every Woman Garden Independent Katie Pruitt Single/Look the Other Way Rounder/Concord Midnight Callers Jem Records Celebrates John Lennon/Jealous Guy Jem Loft Club Dreaming the Impossible/You Are the Sun Independent Spins this Past Week 1 23 Gorillaz Song Machine/The Valley of the Pagans Parlophone/Warner 2 22 Nude Party Midnight Manor/Cities New West 2 22 Cliff Hillis Life Gets Strange/Let’s Pretend Independent 2 22 Second Hand Mojo Open Up Your Mind/Open Up Your Mind Independent 2 22 Juni Ata Saudade/Not Going Anywhere Independent 6 21 Tobin Sprout Empty Horses/Every