Sex Robot and Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 the Erotic Ronald De Sousa and Arina Pismenny [Penultimate

The Erotic Ronald de Sousa and Arina Pismenny [Penultimate version of chapter (in English) in J. Deonna and E. Tieffenbach (ed.) A Small Treatise on Values (Petit Traité des Valeurs). Paris: Editions d’Ithaque. Consult published version to quote.] Nowadays, the erotic is everywhere: the term is applied to works of art, advertising, clothing, gestures, and many other things. It is not, however, always used appropriately. The erotic, for example, is sometimes confused with what triggers sexual arousal. Causing sexual arousal is not sufficient, however, because direct stimulation, by genital friction or brain probe, would not plausibly be called erotic. Neither is it necessary: for just as one may understand why something is funny without being moved to laughter, so one might perceive that something is erotic without experiencing any arousal. What, then, is the erotic, and in what sense can one say that it is a value? The erotic, value, and teleology Is the erotic a value? Or does it have value? If something is a value, its presence can confer some degree of importance on other things. If it has a value, then its benefits derive ultimately from some characteristic which itself has intrinsic value. What nobody cares or could care about is necessarily devoid of it; thus, in order to understand the erotic as a value, we must understand to what states of mind and to what mechanism it is linked, as well as how we care about it and for what reason. Although the erotic cannot be identified with either arousal or desire, the three are evidently linked. -

List of Paraphilias

List of paraphilias Paraphilias are sexual interests in objects, situations, or individuals that are atypical. The American Psychiatric Association, in its Paraphilia Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, Fifth Edition (DSM), draws a Specialty Psychiatry distinction between paraphilias (which it describes as atypical sexual interests) and paraphilic disorders (which additionally require the experience of distress or impairment in functioning).[1][2] Some paraphilias have more than one term to describe them, and some terms overlap with others. Paraphilias without DSM codes listed come under DSM 302.9, "Paraphilia NOS (Not Otherwise Specified)". In his 2008 book on sexual pathologies, Anil Aggrawal compiled a list of 547 terms describing paraphilic sexual interests. He cautioned, however, that "not all these paraphilias have necessarily been seen in clinical setups. This may not be because they do not exist, but because they are so innocuous they are never brought to the notice of clinicians or dismissed by them. Like allergies, sexual arousal may occur from anything under the sun, including the sun."[3] Most of the following names for paraphilias, constructed in the nineteenth and especially twentieth centuries from Greek and Latin roots (see List of medical roots, suffixes and prefixes), are used in medical contexts only. Contents A · B · C · D · E · F · G · H · I · J · K · L · M · N · O · P · Q · R · S · T · U · V · W · X · Y · Z Paraphilias A Paraphilia Focus of erotic interest Abasiophilia People with impaired mobility[4] Acrotomophilia -

2018 Juvenile Law Cover Pages.Pub

2018 JUVENILE LAW SEMINAR Juvenile Psychological and Risk Assessments: Common Themes in Juvenile Psychology THURSDAY MARCH 8, 2018 PRESENTED BY: TIME: 10:20 ‐ 11:30 a.m. Dr. Ed Connor Connor and Associates 34 Erlanger Road Erlanger, KY 41018 Phone: 859-341-5782 Oppositional Defiant Disorder Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Conduct Disorder Substance Abuse Disorders Disruptive Impulse Control Disorder Mood Disorders Research has found that screen exposure increases the probability of ADHD Several peer reviewed studies have linked internet usage to increased anxiety and depression Some of the most shocking research is that some kids can get psychotic like symptoms from gaming wherein the game blurs reality for the player Teenage shooters? Mylenation- Not yet complete in the frontal cortex, which compromises executive functioning thus inhibiting impulse control and rational thought Technology may stagnate frontal cortex development Delayed versus Instant Gratification Frustration Tolerance Several brain imaging studies have shown gray matter shrinkage or loss of tissue Gray Matter is defined by volume for Merriam-Webster as: neural tissue especially of the Internet/gam brain and spinal cord that contains nerve-cell bodies as ing addicts. well as nerve fibers and has a brownish-gray color During his ten years of clinical research Dr. Kardaras discovered while working with teenagers that they had found a new form of escape…a new drug so to speak…in immersive screens. For these kids the seductive and addictive pull of the screen has a stronger gravitational pull than real life experiences. (Excerpt from Dr. Kadaras book titled Glow Kids published August 2016) The fight or flight response in nature is brief because when the dog starts to chase you your heart races and your adrenaline surges…but as soon as the threat is gone your adrenaline levels decrease and your heart slows down. -

Preview from Notesale.Co.Uk Page 1 of 3

PARAPHILIAS DESCRIPTIONS A Abasiophilia love of (or sexual attraction to) people who use leg braces or other orthopaedic appliances Acousticophilia sexual arousal from certain sounds Acrotomophilia love of (or sexual attraction to) amputees Agalmatophilia sexual attraction to statues or mannequins or immobility Algolagnia sexual pleasure from pain Amaurophilia Sexual arousal by a partner whom one is unable to see due to artificial means, such as being blindfolded or having sex in total darkness. (See: sensory deprivation) Andromimetophilia love of women dressed as men Preview from Notesale.co.uk Apodysophilia desire to undress, see also nudism Apotemnophilia desire to have (or sexual arousal fromPage having) a healthy 1 appendageof 3 (limb, digit, or male genitals) amputated Aquaphilia arousal from water and/or in watery environments, including bathtubs or swimming pools Aretifism sexual attraction to people who are without footwear, in contrast to retifism Asphyxiophilia sexual attraction to asphyxia; also called breath control play; including autoerotic asphyxiation; see medical warnings Autogynephilia love of oneself as a woman (also see Blanchard, Bailey, and Lawrence theory for discussion on controversy) B Biastophilia sexual pleasure from committing rape C Celebriphilia pathological desire to have sex with a celebrity Coprophilia sexual attraction to (or pleasure from) feces Crush fetish sexual arousal from seeing small creatures being crushed by members of the opposite sex, or being crushed oneself D Dacryphilia sexual pleasure in eliciting tears from others or oneself Dendrophilia sexual attraction to trees and other large plants, popularized by the movie "Superstar" with Molly Shannon Diaper fetishism sexual arousal from diapers E Emetophilia (a.k.a. -

A Submissive's Initiative BDSM Checklist

A submissive’s Initiative BDSM Checklist Use this checklist to either gauge your own interests or sit down and go over it with your partner and discuss each topic together. For each activity, there are three answers. The first answer should be, if you’ve ever tried that activity before • Yes = I have participated in this activity before • No = I have not participated in this activity before The second answer should be your interest in engaging in that activity on a scale of 0 – 5. • 0 = I have no interest/don’t like this. • 1 = Not very interesting/don’t really enjoy this too much. • 2 = This is alright. • 3 = This is nice/fun/interesting • 4 = I really enjoy/think I’ll enjoy this activity • 5 = I LOVE THIS/CAN’T WAIT TO TRY THIS The third Answer would be to write any explanations or more information after your answers. Remember, the more information you have the safer/hotter/more fun things will be. Examples: Flogging: Yes/5 - I especially love to be flogged on my back!!! Tickling: Yes/5 - My feet are my most ticklish place but I didn’t tell you that! SEX: Boxing / Closeting: Anal Sex: Caging: Armpit Sex: Cock Bondage: Ass Cheek Sex: Cuffs Leather: Butt Plugs: Cuffs Metal: Dildo – Anal: Duct Tape: Dildo – Oral: Full Head Hoods: Genital Intercourse: Gags – ball type: Hand Job: Gags – bits: Including others: Gags – cloth: Licking: Gags – inflatable: Massage: Gags – phallic: Oral Sex: Gags – tap: Strap On: Gas Masks: Swinging: Gates of Hell: Teasing: Harnessing – leather: Vibrators: Harnessing – rope: BONDAGE: Headphone/Earplugs: Blindfolds: -

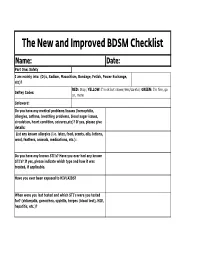

The New and Improved BDSM Checklist

The New and Improved BDSM Checklist Name: Date: Part One: Safety I am mainly into: (D/s, Sadism, Masochism, Bondage, Fetish, Power Exchange, etc)? RED: Stop; YELLOW: I'm ok but slower/less/careful; GREEN: I'm fine, go Saftey Codes: on, more Safeword: Do you have any medical problems/issues (hemophilia, allergies, asthma, breathing problems, blood sugar issues, circulation, heart condition, seizures,etc)? If yes, please give details: List any known allergies (i.e. latex, food, scents, oils, lotions, wool, feathers, animals, medications, etc.): Do you have any known STI's? Have you ever had any known STI's? If yes, please indicate which type and how it was treated, if applicable. Have you ever been exposed to HIV/AIDS? When were you last tested and which STI's were you tested for? (chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis, herpes (blood test), HIV, hepatitis, etc.)? Have you received any STI vaccinations (i.e. hepatitis A & B or HPV)? How often do you practice safe sex (always, most of the time, some of the time, never)? Please explain reasons for not doing so. Medications: Have you taken any medication, including Asprin within the last 4-6 hours (Asprin changes your blood's clotting time). Please include a list of all prescription and over the counter medications you are currently taking: Visible brusies, cuts, or marks must be avoided (yes or no)? Please list any no hit zones, if any: Do you have any phobias or fears that the Dom/Domme should be aware of (blood, needles, enclosed areas, etc.)? Do you want aftercare (yes, no, only in certain circumstances, unsure, etc.)? Please explain. -

Nuisance Sex Behaviors ❖ ❖ ❖

04-Holmes-45515.qxd 5/28/2008 3:12 PM Page 63 4 Nuisance Sex Behaviors ❖ ❖ ❖ There are many sexual behaviors that are completely abhorrent to the senses of most Americans. These practices become more visible as scores of sex offenders are placed in correctional institutions through- out the United States. Sex offenders in prisons currently number more than 234,000 (Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2004). The preponderance of those offenders are involved in rape and other violent sex crimes. However, there is a growing amount Erotolalia of serious literature that suggests that Deriving major sexual satisfaction from many rapists, lust murderers, and sexu- talking about or listening to talk about sex ally motivated serial murderers have Erotomania histories of sexual behavior that reflect A compulsive interest in sexual matters patterns that in the past have been con- sidered only nuisances—not behaviors to become seriously concerned about (Holmes & Holmes, 2001; Masters & Robertson, 1990; McCarthy, 1984). Rosenfield (1985), for example, found that 62% of sex offenders in a prison sample revealed deviant sexual acts other than those for which they were sent to prison. This position will be reinforced by other stud- ies we will cite later in this chapter. They admitted to sex acts such as incest, frottage, voyeurism, and bestiality. Sexual acts that cause no obvious physical harm to the practitioner or the victim we term nuisance sex behaviors. This chapter is devoted to discussion of these activities. 63 04-Holmes-45515.qxd 5/28/2008 3:12 PM Page 64 64 SEX CRIMES Nuisance sex behaviors are often viewed in a less serious fashion than sex crimes that cause serious trauma and death. -

PORNOGRAPHY AS a CONTRIBUTORY RISK FACTOR in the PSYCHO-SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT of VIOLENT SEX OFFENDERS Thomas J

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Spring 5-2007 CRIMINAL SEXUALITY AND PSYCHOPATHOLOGY: PORNOGRAPHY AS A CONTRIBUTORY RISK FACTOR IN THE PSYCHO-SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT OF VIOLENT SEX OFFENDERS Thomas J. Tiefenwerth University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Applied Behavior Analysis Commons, Clinical Psychology Commons, Criminology Commons, Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons, Domestic and Intimate Partner Violence Commons, and the Legal Theory Commons Recommended Citation Tiefenwerth, Thomas J., "CRIMINAL SEXUALITY AND PSYCHOPATHOLOGY: PORNOGRAPHY AS A CONTRIBUTORY RISK FACTOR IN THE PSYCHO-SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT OF VIOLENT SEX OFFENDERS" (2007). Dissertations. 1255. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/1255 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi CRIMINAL SEXUALITY AND PSYCHOPATHOLOGY: PORNOGRAPHY AS A CONTRIBUTORY RISK FACTOR IN THE PSYCHO-SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT OF VIOLENT SEX OFFENDERS by Thomas J. Tiefenwerth A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Studies Office of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Appr< May 2007 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. COPYRIGHT BY THOMAS J. TIEFENWERTH 2007 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. The University of Southern Mississippi CRIMINAL SEXUALITY AND PSYCHOPATHOLOGY: PORNOGRAPHY AS A CONTRIBUTORY RISK FACTOR IN THE PSYCHO-SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT OF VIOLENT SEX OFFENDERS by Thomas J. -

Intimate Relationships with Artificial Partners

Intimate relationships with artificial partners Citation for published version (APA): Levy, D. (2007). Intimate relationships with artificial partners. Datawyse / Universitaire Pers Maastricht. https://doi.org/10.26481/dis.20071011dl Document status and date: Published: 01/01/2007 DOI: 10.26481/dis.20071011dl Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Please check the document version of this publication: • A submitted manuscript is the version of the article upon submission and before peer-review. There can be important differences between the submitted version and the official published version of record. People interested in the research are advised to contact the author for the final version of the publication, or visit the DOI to the publisher's website. • The final author version and the galley proof are versions of the publication after peer review. • The final published version features the final layout of the paper including the volume, issue and page numbers. Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. If the publication is distributed under the terms of Article 25fa of the Dutch Copyright Act, indicated by the “Taverne” license above, please follow below link for the End User Agreement: www.umlib.nl/taverne-license Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us at: [email protected] providing details and we will investigate your claim. -

Amputee Fetishism Acrotomophilia Is an Intense Desire for One's Partner to Be an Amputee

Paraphilias Amputee fetishism Acrotomophilia is an intense desire for one's partner to be an amputee. Apotemnophilia is an intense desire to be an amputee. Boxing Helena Grindhouse Amputee fetishism in Literature Flannery O’Connor’s short story “Good Country People” features a character whose prosthetic leg is stolen. The man who steals her leg travels about the country stealing people’s prosthetics limbs– legs, a glass eye. Venus de Milo Statuephilia also called agalmatophilia, or Pygmalionism after the myth of Pygmalion, is an uncommon sexual fetish that involves sexual attraction to statues or dolls. Pygmalion & Galatea by Jean-Leon Gerome 19th C Schediaphilia (aka toonophilia) sexual attraction to cartoon or anime characters. Galactophilia: (a.k.a lactophilia) sexual attraction to human milk or lactating women “Roman Charity” Story known from old paintings showing a young woman nourishing an imprisoned old man by suckling him. Also, The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck & The White Hotel by D.M. Thomas Symphorophili a: sexual attraction with stage- managing a disaster, such as a traffic accident Urolagnia (also known as urophilia or undinism) sexual pleasure from urine & urination. Havelock Ellis - British sexologist who was aroused by seeing women urinate. Suggested Rembrandt also enjoyed the practice, claiming it explained the golden tones of his paintings. Voyeurism: sexual pleasure from observing other people. Zoophilia An affinity or sexual attraction by a human to a non-human animal. Europa & the Bull Moreau, 1869 The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife, an 1820 woodcut depicting a woman dreaming of a sexual encounter with a pair of octopi. -

The Kinky Renaissance’S Seminar, I Will Take on the Art of Edging As My Foray Into Early Modern Modes of Contemporary Kink Culture

Beatrice Bradley Early Modern Money Shots In The Color of Kink, Ariane Cruz writes of the tension between the so-called “money shot” and bareback sex, asking, “if the money shot depends on visual proof of pleasure in the projection of semen on the body and the practice of bareback sex is contingent upon ejaculate deposited inside the body, how can bareback porn reconcile this representational quandary—rendering visible what is invisible while remaining a kind of ‘visual archive’ of bareback sex itself?” This paper takes as its focus “this representational quandary” in early modern contexts, from the Bower of Bliss to Venus and Adonis: I chart the movement between stylized representations of sweat and tears projected on the body—the pearly sweat, for example, that adorns Acrasia—and the tactile melting such fluids produce, hands joined in sweaty rapture or Venus’s tears dissolving on her cheeks. I read the pearly liquid that decorates bodies in my text of focus as in fact analogous to the contemporary slang of the pearl necklace, and I argue that clasped moist hands function to make legible to a reader the fluidic exchange of sexual activity that is otherwise hidden, interior. In even the most explicit forms of pornography, fluidic exchange—rather than the projection of fluid—is almost always hidden from sight, deposited rather than external. Although I focus primarily on the early modern literary, I also ask us to retheorize in the contemporary the projection of fluid on a body and its visual impact. Erika Lyn Carbonara “The Happiest State that Ever Man Was Born to”: Contextualizing Cuckoldry within the Kinky Early Modern In Thomas Middleton’s city comedy A Chaste Maid in Cheapside, marital norms are stretched to the extreme: a husband-and-wife must separate because of their fecundity, a Cambridge-educated man is betrothed to a Welsh prostitute, and, notably, the Allwits’ curious extramarital relationship with Sir Walter Whorehound, who enjoys a sexual relationship with Mrs. -

Bodily Fluids in Antiquity

BODILY FLUIDS IN ANTIQUITY From ancient Egypt to Imperial Rome, from Greek medicine to early Christianity, this volume examines how human bodily fluids influenced ideas about gender, sexuality, politics, emotions, and morality, and how those ideas shaped later European thought. Comprising 24 chapters across seven key themes—language, gender, eroticism, nutrition, dissolution, death, and afterlife—this volume investigates bodily fluids in the context of the current sensory turn. It asks fundamental questions about physicality and fluidity: how were bodily fluids categorised and differentiated? How were fluids trapped inside the body perceived, and how did this perception alter when those fluids were externalised? Do ancient approaches complement or challenge our modern sensibilities about bodily fluids? How were religious practices influenced by attitudes towards bodily fluids, and how did religious authorities attempt to regulate or restrict their appearance? Why were some fluids taboo and others cherished? In what ways were bodily fluids gendered? Offering a range of scholarly approaches and voices, this volume explores how ideas about the body and the fluids it contained and externalised are culturally conditioned and ideologically determined. The analysis encompasses the key geographic centres of the ancient Mediterranean basin, including Greece, Rome, Byzantium, and Egypt. By taking a longue durée perspective across a richly intertwined set of territories, this collection is the first to provide a comprehensive, wide-ranging study of bodily fluids in the ancient world. Bodily Fluids in Antiquity will be of particular interest to academic readers working in the fields of classics and its reception, archaeology, anthropology, and ancient to Early Modern history. It will also appeal to more general readers with an interest in the history of the body and history of medicine.