Technosexualities and the Desire for Machinic Bodies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

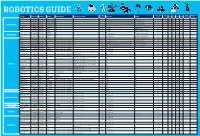

Robotics Section Guide for Web.Indd

ROBOTICS GUIDE Soldering Teachers Notes Early Higher Hobby/Home The Robot Product Code Description The Brand Assembly Required Tools That May Be Helpful Devices Req Software KS1 KS2 KS3 KS4 Required Available Years Education School VEX 123! 70-6250 CLICK HERE VEX No ✘ None No ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ Dot 70-1101 CLICK HERE Wonder Workshop No ✘ iOS or Android phones/tablets. Apps are also available for Kindle. Free Apps to download ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ Dash 70-1100 CLICK HERE Wonder Workshop No ✘ iOS or Android phones/tablets. Apps are also available for Kindle. Free Apps to download ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ Ready to Go Robot Cue 70-1108 CLICK HERE Wonder Workshop No ✘ iOS or Android phones/tablets. Apps are also available for Kindle. Free Apps to download ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ Codey Rocky 75-0516 CLICK HERE Makeblock No ✘ PC, Laptop Free downloadb ale Mblock Software ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ Ozobot 70-8200 CLICK HERE Ozobot No ✘ PC, Laptop Free downloads ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ Ohbot 76-0000 CLICK HERE Ohbot No ✘ PC, Laptop Free downloads for Windows or Pi ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ SoftBank NAO 70-8893 CLICK HERE No ✘ PC, Laptop or Ipad Choregraph - free to download ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ Robotics Humanoid Robots SoftBank Pepper 70-8870 CLICK HERE No ✘ PC, Laptop or Ipad Choregraph - free to download ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ Robotics Ohbot 76-0001 CLICK HERE Ohbot Assembly is part of the fun & learning! ✘ PC, Laptop Free downloads for Windows or Pi ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ FABLE 00-0408 CLICK HERE Shape Robotics Assembly is part of the fun & learning! ✘ PC, Laptop or Ipad Free Downloadable ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ VEX GO! 70-6311 CLICK HERE VEX Assembly is part of the fun & learning! ✘ Windows, Mac, -

Martine Rothblatt

For more information contact us on: North America 855.414.1034 International +1 646.307.5567 [email protected] Martine Rothblatt Topics Activism and Social Justice, Diversity and Inclusion, Health and Wellness, LGBTQIA+, Lifestyle, Science and Technology Travels From Maryland Bio Martine Rothblatt, Ph.D., MBA, J.D. is one of the most exciting and innovative voices in the world of business, technology, and medicine. She was named by Forbes as one of the "100 Greatest Living Business Minds of the past 100 years" and one of America's Self-Made Women of 2019. After graduating from UCLA with a law and MBA degree, Martine served as President & CEO of Dr. Gerard K. O’Neill’s satellite navigation company, Geostar. The satellite system she launched in 1986 continues to operate today, providing service to certain government agencies. She also created Sirius Satellite Radio in 1990, serving as its Chairman and CEO. In the years that followed, Martine Rothblatt’s daughter was diagnosed with life-threatening pulmonary hypertension. Determined to find a cure, she left the communications business and entered the world of medical biotechnology. She earned her Ph.D. in medical ethics at the Royal London College of Medicine & Dentistry and founded the United Therapeutics Corporation in 1996. The company focuses on the development and commercialization of page 1 / 4 For more information contact us on: North America 855.414.1034 International +1 646.307.5567 [email protected] biotechnology in order to address the unmet medical needs of patients with chronic and life-threatening conditions. Since then, she has become the highest-paid female CEO in America. -

A Production Process for Developing a Web Series, Snaptv

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations Office of aduateGr Studies 12-2017 A PRODUCTION PROCESS FOR DEVELOPING A WEB SERIES, SNAPTV Toebey T. Caldwell Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd Part of the Acting Commons, Dramatic Literature, Criticism and Theory Commons, Other Theatre and Performance Studies Commons, Performance Studies Commons, Playwriting Commons, and the Television Commons Recommended Citation Caldwell, Toebey T., "A PRODUCTION PROCESS FOR DEVELOPING A WEB SERIES, SNAPTV" (2017). Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations. 588. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd/588 This Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Office of aduateGr Studies at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A PRODUCTION PROCESS FOR DEVELOPING A WEB SERIES, SNAPTV A Project Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies: Film Theory and Media Production by Toebey Ty Caldwell December 2017 A PRODUCTION PROCESS FOR DEVELOPING A WEB SERIES, SNAPTV A Project Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Toebey Ty Caldwell December 2017 Approved by: Kathryn Ervin, Committee Chair, Theatre Arts Andre Harrington, Theatre Arts C. Rod Metts, Communication Studies © 2017 Toebey Ty Caldwell ABSTRACT My project for this Interdisciplinary Master’s Program, studying Film Theories and Media Production methods, details “A Production Process for Creating a Web Series, called SNAPtv”. -

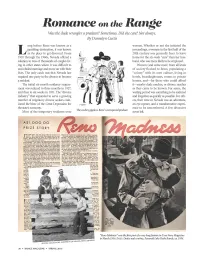

Romance on Tlw Range Was the Dude Wrangler a Predator? Sometimes

Romance on tlw Range Was the dude wrangler a predator? Sometimes. Did she care? Not always. By Donnelyn Curtis ong before Reno was known as a women. Whether or not she initiated the gambling destination, it was known proceedings, a woman in the first half of the L as the place to get divorced. From 20th century was generally freer to leave 1910 through the 1960s, Nevada offered a home for the six-week "cure" than her hus solution to tens of thousands of couples liv band, who was more likely to be employed. ing in other states where it was difficult to Women (and some men) from all levels end a failed marriage and move on with their of society flocked to Reno, populating a lives. The only catch was that Nevada law "colony" with its own culture, living in required one party in the divorce to become hotels, boardinghouses, rooms in private a resident. homes, and- for those who could afford The initial six-month residency require it- nearby dude ranches, or divorce ranches ment was reduced to three months in 1927, as they came to be known. For some, the and then to six weeks in 1931. The "divorce waiting period was something to be endured industry" that expanded to serve a growing and forgotten as quickly as possible. For oth number of migratory divorce seekers cush ers, their time in Nevada was an adventure, ioned the blow of the Great Depression for an eye-opener, and a transformative experi the state's economy. ence to be remembered. -

Podcasts and Convergent Digital Media Michael Dwyer, Arcadia University

Podcasts and Convergent Digital Media Michael Dwyer, Arcadia University What is a podcast, anyway? Is it a textual form? A genre of audio recording? A distribution method? And what was a podcast ten years ago? Are they different now from how they were then? How so? Why? Those are important questions. But it appears that media studies, as a discipline, has yet to pursue them in any sustained way. The word “podcast” has appeared in Cinema Journal in only 11 pieces, mostly in announcements and citations. In Velvet Light Trap, the word’s appeared twice. Major academic publishers like Routledge have only a few podcasting monographs, mostly of the how-to variety. Run a search on the term “podcast” on Flow and you get 41 results. A single television series like Battlestar Galactica, by contrast, returns 46 results. What might explain this relative silence from a group of scholars whose animating purpose is the study of popular media? I am reminded, as I often am, of Tim Anderson’s 2009 Velvet Light Trap essay “A Skip in the Record of Media Studies.” In it, Anderson argues that media studies' failure to fully embrace the study of sound media has "unwittingly articulated blind spots that make it unable to fully understand what is at stake today" (104). Consider, for example the roundtable prompt that animates our discussion, which articulates a desire to consider podcasts “alongside other popular forms, such as web series and online television,” but not sound media. If media studies scholars want to understand podcasts (and I think we all here sincerely do) we need to understand them in relation to media industries like radio, pop music, and sound recording as well as screen media. -

Cybernetic Human HRP-4C: a Humanoid Robot with Human-Like Proportions

Cybernetic Human HRP-4C: A humanoid robot with human-like proportions Shuuji KAJITA, Kenji KANEKO, Fumio KANEIRO, Kensuke HARADA, Mitsuharu MORISAWA, Shin’ichiro NAKAOKA, Kanako MIURA, Kiyoshi FUJIWARA, Ee Sian NEO, Isao HARA, Kazuhito YOKOI, Hirohisa HIRUKAWA Abstract Cybernetic human HRP-4C is a humanoid robot whose body dimensions were designed to match the average Japanese young female. In this paper, we ex- plain the aim of the development, realization of human-like shape and dimensions, research to realize human-like motion and interactions using speech recognition. 1 Introduction Cybernetics studies the dynamics of information as a common principle of com- plex systems which have goals or purposes. The systems can be machines, animals or a social systems, therefore, cybernetics is multidiciplinary from its nature. Since Norbert Wiener advocated the concept in his book in 1948[1], the term has widely spreaded into academic and pop culture. At present, cybernetics has diverged into robotics, control theory, artificial intelligence and many other research fields, how- ever, the original unified concept has not yet lost its glory. Robotics is one of the biggest streams that branched out from cybernetics, and its goal is to create a useful system by combining mechanical devices with information technology. From a practical point of view, a robot does not have to be humanoid; nevertheless we believe the concept of cybernetics can justify the research of hu- manoid robots for it can be an effective hub of multidiciplinary research. WABOT-1, -

The Influence of Anonymity on Participation in Online Communities

Thèse de doctorat de l’UTT Malte PASKUDA The Influence of Anonymity on Participation in Online Communities Spécialité : Ingénierie Sociotechnique des Connaissances, des Réseaux et du Développement Durable 2016TROY0033 Année 2016 THESE pour l’obtention du grade de DOCTEUR de l’UNIVERSITE DE TECHNOLOGIE DE TROYES Spécialité : INGENIERIE SOCIOTECHNIQUE DES CONNAISSANCES, DES RESEAUX ET DU DEVELOPPEMENT DURABLE présentée et soutenue par Malte PASKUDA le 24 octobre 2016 The Influence of Anonymity on Participation in Online Communities JURY M. M. BAKER DIRECTEUR DE RECHERCHE CNRS Président (Rapporteur) Mme N. GAUDUCHEAU MAITRE DE CONFERENCES Examinateur Mme M. LEWKOWICZ PROFESSEUR DES UNIVERSITES Directeur de thèse M. M. PRILLA PROFESSOR Rapporteur M. M. ROHDE DOKTOR Examinateur Acknowledgements Myriam Lewkowicz Michael Baker Michael Prilla Nadia Gauducheau Markus Rohde Michel Marcoccia Valentin Berthou Matthieu Tixier Hassan Atifi Ines Di Loreto Karine Lan Lorraine Tosi Aurlien Bruel Khuloud Abou Amsha Josslyn Beltran Madrigal Les membres de lquipe Tech-CICO et les membres du projet TOPIC trouvent ici mes remerciements les plus sincres. Abstract This work presents my PhD thesis about the influence of anonymity on par- ticipation in online environments. The starting point of this research was the observation of the design process of an online platform for informal caregivers. I realized that there is no knowledge about the practical effects that an anony- mous identity system would have. This thesis contains the subsequent literature review, which has been synthesized into a model that shows which participation factors might be influenced by anonymity. Three studies on existing online en- vironments have been conducted: One on Youtube, where there was a change in the comment system forbidding anonymous comments; one on Quora, where users can choose to answer questions anonymously; and one on Hacker News, where users choose how many identity factors they want to present and which name they use. -

Fetishism and the Culture of the Automobile

FETISHISM AND THE CULTURE OF THE AUTOMOBILE James Duncan Mackintosh B.A.(hons.), Simon Fraser University, 1985 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Communication Q~amesMackintosh 1990 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY August 1990 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL NAME : James Duncan Mackintosh DEGREE : Master of Arts (Communication) TITLE OF THESIS: Fetishism and the Culture of the Automobile EXAMINING COMMITTEE: Chairman : Dr. William D. Richards, Jr. \ -1 Dr. Martih Labbu Associate Professor Senior Supervisor Dr. Alison C.M. Beale Assistant Professor \I I Dr. - Jerry Zqlove, Associate Professor, Department of ~n~lish, External Examiner DATE APPROVED : 20 August 1990 PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENCE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University the right to lend my thesis or dissertation (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Title of Thesis/Dissertation: Fetishism and the Culture of the Automobile. Author : -re James Duncan Mackintosh name 20 August 1990 date ABSTRACT This thesis explores the notion of fetishism as an appropriate instrument of cultural criticism to investigate the rites and rituals surrounding the automobile. -

1 the Erotic Ronald De Sousa and Arina Pismenny [Penultimate

The Erotic Ronald de Sousa and Arina Pismenny [Penultimate version of chapter (in English) in J. Deonna and E. Tieffenbach (ed.) A Small Treatise on Values (Petit Traité des Valeurs). Paris: Editions d’Ithaque. Consult published version to quote.] Nowadays, the erotic is everywhere: the term is applied to works of art, advertising, clothing, gestures, and many other things. It is not, however, always used appropriately. The erotic, for example, is sometimes confused with what triggers sexual arousal. Causing sexual arousal is not sufficient, however, because direct stimulation, by genital friction or brain probe, would not plausibly be called erotic. Neither is it necessary: for just as one may understand why something is funny without being moved to laughter, so one might perceive that something is erotic without experiencing any arousal. What, then, is the erotic, and in what sense can one say that it is a value? The erotic, value, and teleology Is the erotic a value? Or does it have value? If something is a value, its presence can confer some degree of importance on other things. If it has a value, then its benefits derive ultimately from some characteristic which itself has intrinsic value. What nobody cares or could care about is necessarily devoid of it; thus, in order to understand the erotic as a value, we must understand to what states of mind and to what mechanism it is linked, as well as how we care about it and for what reason. Although the erotic cannot be identified with either arousal or desire, the three are evidently linked. -

Address Munging: the Practice of Disguising, Or Munging, an E-Mail Address to Prevent It Being Automatically Collected and Used

Address Munging: the practice of disguising, or munging, an e-mail address to prevent it being automatically collected and used as a target for people and organizations that send unsolicited bulk e-mail address. Adware: or advertising-supported software is any software package which automatically plays, displays, or downloads advertising material to a computer after the software is installed on it or while the application is being used. Some types of adware are also spyware and can be classified as privacy-invasive software. Adware is software designed to force pre-chosen ads to display on your system. Some adware is designed to be malicious and will pop up ads with such speed and frequency that they seem to be taking over everything, slowing down your system and tying up all of your system resources. When adware is coupled with spyware, it can be a frustrating ride, to say the least. Backdoor: in a computer system (or cryptosystem or algorithm) is a method of bypassing normal authentication, securing remote access to a computer, obtaining access to plaintext, and so on, while attempting to remain undetected. The backdoor may take the form of an installed program (e.g., Back Orifice), or could be a modification to an existing program or hardware device. A back door is a point of entry that circumvents normal security and can be used by a cracker to access a network or computer system. Usually back doors are created by system developers as shortcuts to speed access through security during the development stage and then are overlooked and never properly removed during final implementation. -

Romantic Realism

Romantic Realism http://www.thebookoflife.org/romantic-realism/ INTRODUCTION: We expect love to be the source of our greatest joys. But it is – of course – in practice, one of the most reliable routes to misery. Few forms of suffering are ever as intense as those we experience in relationships. Viewed from outside, love could be mistaken for a practice focused almost entirely on the generation of despair. We should, at least, try to understand our sorrows. Understanding does not magically remove problems, but it sets them in context, reduces our sense of isolation and persecution and helps us to accept that certain griefs are highly normal. The purpose of this essay is to help us develop an emotional skill we term Romantic Realism, defined as a correct awareness of what can legitimately be expected of love and the reasons why we will for large stretches of our lives be very disappointed by it, for no especially sinister or personal reasons. The problems begin because, despite all the statistics, we are inveterate optimists about how love should go. No amount of information seems able to shake us from our faith in love. A thousand divorces pass our doors; none seem relevant to us. We see relationship difficulties unfold around us all the time. But we retain a remarkable capacity to discount negative information. Despite the evidence of failures and loneliness, we cling to some highly ambitious background ideas of what relationships should be like – even if we have in reality never seen such unions in train anywhere near us. The ideal relationship is the equivalent of the snow leopard; our loyalty to it as a realistic possibility cannot be based on the evidence of our own experience. -

History of Robotics: Timeline

History of Robotics: Timeline This history of robotics is intertwined with the histories of technology, science and the basic principle of progress. Technology used in computing, electricity, even pneumatics and hydraulics can all be considered a part of the history of robotics. The timeline presented is therefore far from complete. Robotics currently represents one of mankind’s greatest accomplishments and is the single greatest attempt of mankind to produce an artificial, sentient being. It is only in recent years that manufacturers are making robotics increasingly available and attainable to the general public. The focus of this timeline is to provide the reader with a general overview of robotics (with a focus more on mobile robots) and to give an appreciation for the inventors and innovators in this field who have helped robotics to become what it is today. RobotShop Distribution Inc., 2008 www.robotshop.ca www.robotshop.us Greek Times Some historians affirm that Talos, a giant creature written about in ancient greek literature, was a creature (either a man or a bull) made of bronze, given by Zeus to Europa. [6] According to one version of the myths he was created in Sardinia by Hephaestus on Zeus' command, who gave him to the Cretan king Minos. In another version Talos came to Crete with Zeus to watch over his love Europa, and Minos received him as a gift from her. There are suppositions that his name Talos in the old Cretan language meant the "Sun" and that Zeus was known in Crete by the similar name of Zeus Tallaios.