Flora of a Cool Temperate Forest Around Restoration Center for Endangered Species, Yeongyang

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UPDATED 18Th February 2013

7th February 2015 Welcome to my new seed trade list for 2014-15. 12, 13 and 14 in brackets indicates the harvesting year for the seed. Concerning seed quantity: as I don't have many plants of each species, seed quantity is limited in most cases. Therefore, for some species you may only get a few seeds. Many species are harvested in my garden. Others are surplus from trade and purchase. OUT: Means out of stock. Sometimes I sell surplus seed (if time allows), although this is unlikely this season. NB! Cultivars do not always come true. I offer them anyway, but no guarantees to what you will get! Botanical Name (year of harvest) NB! Traditional vegetables are at the end of the list with (mostly) common English names first. Acanthopanax henryi (14) Achillea sibirica (13) Aconitum lamarckii (12) Achyranthes aspera (14, 13) Adenophora khasiana (13) Adenophora triphylla (13) Agastache anisata (14,13)N Agastache anisata alba (13)N Agastache rugosa (Ex-Japan) (13) (two varieties) Agrostemma githago (13)1 Alcea rosea “Nigra” (13) Allium albidum (13) Allium altissimum (Persian Shallot) (14) Allium atroviolaceum (13) Allium beesianum (14,12) Allium brevistylum (14) Allium caeruleum (14)E Allium carinatum ssp. pulchellum (14) Allium carinatum ssp. pulchellum album (14)E Allium carolinianum (13)N Allium cernuum mix (14) E/N Allium cernuum “Dark Scape” (14)E Allium cernuum ‘Dwarf White” (14)E Allium cernuum ‘Pink Giant’ (14)N Allium cernuum x stellatum (14)E (received as cernuum , but it looks like a hybrid with stellatum, from SSE, OR KA A) Allium cernuum x stellatum (14)E (received as cernuum from a local garden centre) Allium clathratum (13) Allium crenulatum (13) Wild coll. -

Systematic Studies of the South African Campanulaceae Sensu Stricto with an Emphasis on Generic Delimitations

Town The copyright of this thesis rests with the University of Cape Town. No quotation from it or information derivedCape from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of theof source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non-commercial research purposes only. University Systematic studies of the South African Campanulaceae sensu stricto with an emphasis on generic delimitations Christopher Nelson Cupido Thesis presented for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of Botany Town UNIVERSITY OF CAPECape TOWN of September 2009 University Roella incurva Merciera eckloniana Microcodon glomeratus Prismatocarpus diffusus Town Wahlenbergia rubioides Cape of Wahlenbergia paniculata (blue), W. annularis (white) Siphocodon spartioides University Rhigiophyllum squarrosum Wahlenbergia procumbens Representatives of Campanulaceae diversity in South Africa ii Town Dedicated to Ursula, Denroy, Danielle and my parents Cape of University iii Town DECLARATION Cape I confirm that this is my ownof work and the use of all material from other sources has been properly and fully acknowledged. University Christopher N Cupido Cape Town, September 2009 iv Systematic studies of the South African Campanulaceae sensu stricto with an emphasis on generic delimitations Christopher Nelson Cupido September 2009 ABSTRACT The South African Campanulaceae sensu stricto, comprising 10 genera, represent the most diverse lineage of the family in the southern hemisphere. In this study two phylogenies are reconstructed using parsimony and Bayesian methods. A family-level phylogeny was estimated to test the monophyly and time of divergence of the South African lineage. This analysis, based on a published ITS phylogeny and an additional ten South African taxa, showed a strongly supported South African clade sister to the campanuloids. -

Dispersion of Vascular Plant in Mt. Huiyangsan, Korea

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Journal of Korean Nature Vol. 3, No. 1 1-10, 2010 Dispersion of Vascular Plant in Mt. Huiyangsan, Korea Hyun-Tak Shin1, Sung-Tae Yoo2, Byung-Do Kim2, and Myung-Hoon YI3* 1Gyeongsangnam-do Forest Environment Research Institute, Jinju 660-871, Korea 2Daegu Arboretum 284 Daegok-Dong Dalse-Gu Daegu 704-310, Korea 3Department of Landscape Architecture, Graduate School, Yeungnam University, Gyeongsan 712-749, Korea Abstract: We surveyed that vascular plants can be classified into 90 families and 240 genus, 336 species, 69 variants, 22 forms, 3 subspecies, total 430 taxa. Dicotyledon plant is 80.9%, monocotyledon plant is 9.8%, Pteridophyta is 8.1%, Gymnosermae is 1.2% among the whole plant family. Rare and endangered plants are Crypsinus hastatus, Lilium distichum, Viola albida, Rhododendron micranthum, totalling four species. Endemic plants are Carex okamotoi, Salix koriyanagi for. koriyanagi, Clematis trichotoma, Thalictrum actaefolium var. brevistylum, Galium trachyspermum, Asperula lasiantha, Weigela subsessilis, Adenophora verticillata var. hirsuta, Aster koraiensis, Cirsium chanroenicum and Saussurea seoulensis total 11 taxa. Specialized plants are 20 classification for I class, 7 classifications for the II class, 7 classifications for the III class, 2 classification for the IV class, and 1 classification for the V class, total 84 taxa. Naturalized plants specified in this study are 10 types but Naturalization rate is not high compared to the area of BaekDu-DaeGan. This survey area is focused on the center of BaekDu- DaeGan, and it has been affected by excessive investigations and this area has been preserved as Buddhist temples' woods. -

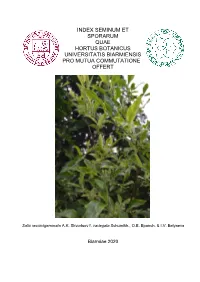

Index Seminum Et Sporarum Quae Hortus Botanicus Universitatis Biarmiensis Pro Mutua Commutatione Offert

INDEX SEMINUM ET SPORARUM QUAE HORTUS BOTANICUS UNIVERSITATIS BIARMIENSIS PRO MUTUA COMMUTATIONE OFFERT Salix recurvigemmata A.K. Skvortsov f. variegata Schumikh., O.E. Epanch. & I.V. Belyaeva Biarmiae 2020 Federal State Autonomous Educational Institution of Higher Education «Perm State National Research University», A.G. Genkel Botanical Garden ______________________________________________________________________________________ СПИСОК СЕМЯН И СПОР, ПРЕДЛАГАЕМЫХ ДЛЯ ОБМЕНА БОТАНИЧЕСКИМ САДОМ ИМЕНИ А.Г. ГЕНКЕЛЯ ПЕРМСКОГО ГОСУДАРСТВЕННОГО НАЦИОНАЛЬНОГО ИССЛЕДОВАТЕЛЬСКОГО УНИВЕРСИТЕТА Syringa vulgaris L. ‘Красавица Москвы’ Пермь 2020 Index Seminum 2020 2 Federal State Autonomous Educational Institution of Higher Education «Perm State National Research University», A.G. Genkel Botanical Garden ______________________________________________________________________________________ Дорогие коллеги! Ботанический сад Пермского государственного национального исследовательского университета был создан в 1922 г. по инициативе и под руководством проф. А.Г. Генкеля. Здесь работали известные ученые – ботаники Д.А. Сабинин, В.И. Баранов, Е.А. Павский, внесшие своими исследованиями большой вклад в развитие биологических наук на Урале. В настоящее время Ботанический сад имени А.Г. Генкеля входит в состав регионального Совета ботанических садов Урала и Поволжья, Совет ботанических садов России, имеет статус научного учреждения и особо охраняемой природной территории. Основными научными направлениями работы являются: интродукция и акклиматизация растений, -

American Fern Journal

AMERICAN FERN JOURNAL QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN FERN SOCIETY Broad-Scale Integrity and Local Divergence in the Fiddlehead Fern Matteuccia struthiopteris (L.) Todaro (Onocleaceae) DANIEL M. KOENEMANN Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden, 1500 North College Avenue, Claremont, CA 91711-3157, e-mail: [email protected] JACQUELINE A. MAISONPIERRE University of Vermont, Department of Plant Biology, Jeffords Hall, 63 Carrigan Drive, Burlington, VT 05405, e-mail: [email protected] DAVID S. BARRINGTON University of Vermont, Department of Plant Biology, Jeffords Hall, 63 Carrigan Drive, Burlington, VT 05405, e-mail: [email protected] American Fern Journal 101(4):213–230 (2011) Broad-Scale Integrity and Local Divergence in the Fiddlehead Fern Matteuccia struthiopteris (L.) Todaro (Onocleaceae) DANIEL M. KOENEMANN Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden, 1500 North College Avenue, Claremont, CA 91711-3157, e-mail: [email protected] JACQUELINE A. MAISONPIERRE University of Vermont, Department of Plant Biology, Jeffords Hall, 63 Carrigan Drive, Burlington, VT 05405, e-mail: [email protected] DAVID S. BARRINGTON University of Vermont, Department of Plant Biology, Jeffords Hall, 63 Carrigan Drive, Burlington, VT 05405, e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT.—Matteuccia struthiopteris (Onocleaceae) has a present-day distribution across much of the north-temperate and boreal regions of the world. Much of its current North American and European distribution was covered in ice or uninhabitable tundra during the Pleistocene. Here we use DNA sequences and AFLP data to investigate the genetic variation of the fiddlehead fern at two geographic scales to infer the historical biogeography of the species. Matteuccia struthiopteris segregates globally into minimally divergent (0.3%) Eurasian and American lineages. -

Annual Benefit Plant Sale 2016 Wildflower

Annual Benefit Plant Sale 2016 Wildflower Gardening on a higher level Celebration Sunday April 24th 10 am - 4 pm 6penG tKe Ga\ in natiYe plant paraGise anG enMo\ JarGeninJ Gemonstrations liYe performanFes plant JiYeawa\s anG free aGmission Mt. Cuba Center opens on April 1st. Visit our website for more information www.mtFubaFenter.orJ 1 %arle\ Mill 5G. +oFNessin '( 1 .. 2 2015 SPRING PLANT SALE CATALOG WEBSITE: http://ag.udel.edu/udbg/events/annualsale.html 2015 SPRING PLANT SALE CATALOG WEBSITE: http://ag.udel.edu/udbg/events/annualsale.html 3 WELCOME to the 24th annual UDBG benefit plant sale, the major source of UDBG funding each year. At the Botanic Gardens, 2016 BENEFIT PLANT SALE CATALOG our primary focus is always students and learning, and 2015 was a great year. Students are integral to almost everything we do, from project installation to plant collections care, to grounds mainte- nance, plant records management, and plant propagation, to name but a few responsibilities. They are undergraduates, graduate stu- dents, master gardeners, and volunteers, and their work is seen and appreciated by industry professionals and visitors. While the sale is a key fundraiser, I hope it is also educational for our customers. This catalog is as much an educational reference as it is a sales inventory; new plants are featured along with old favorites, and the ornamental qualities of less familiar plants are highlighted through our specially selected, featured plants. I greatly appreciate the long-term support of our Friends members. In recognition and appreciation of this support, we will again offer members 10% off their entire purchase under $100, 15% off their purchase of $100 but less than $200, and 20% off their purchase of $200 or more, all plants, all day on Members Day, Thursday only. -

Full Article

Phytotaxa 233 (1): 027–048 ISSN 1179-3155 (print edition) www.mapress.com/phytotaxa/ PHYTOTAXA Copyright © 2015 Magnolia Press Article ISSN 1179-3163 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.233.1.2 Taxonomy and phylogeny of Cercospora spp. from Northern Thailand JEERAPA NGUANHOM1, RATCHADAWAN CHEEWANGKOON1, JOHANNES Z. GROENEWALD2, UWE BRAUN3, CHAIWAT TO-ANUN1* & PEDRO W. CROUS2,4 1Department of Entomology and Plant Pathology, Faculty of Agriculture, Chiang Mai University, 50200, Thailand *email: [email protected] 2CBS-KNAW Fungal Biodiversity Centre, Uppsalalaan 8, 3584 CT Utrecht, The Netherlands 3Martin-Luther-Universität, Institut für Biologie, Bereich Geobotanik und Botanischer Garten, Herbarium, Neuwerk 21, 06099 Halle (Saale), Germany 4Department of Microbiology and Plant Pathology, Forestry and Agricultural Biotechnology Institute, University of Pretoria, Pretoria 0002, South Africa Abstract The genus Cercospora represents a group of important plant pathogenic fungi with a wide geographic distribution, being commonly associated with leaf spots on a broad range of plant hosts. The goal of the present study was to conduct a mor- phological and molecular phylogenetic analysis of the Cercospora spp. occurring on various plants growing in Northern Thailand, an area with a tropical savannah climate, and a rich diversity of vascular plants. Sixty Cercospora isolates were collected from 29 host species (representing 16 plant families). Partial nucleotide sequence data for two gene loci (ITS and cmdA), were generated for all isolates. Results from this study indicate that members of the genus Cercospora vary regarding host specificity, with some taxa having wide host ranges, and others being host-specific. Based on cultural, morphological and phylogenetic data, four new species of Cercospora could be identified: C. -

210 Part 319—Foreign Quarantine Notices

§ 318.82–3 7 CFR Ch. III (1–1–03 Edition) The movement of plant pests, means of 319.8–20 Importations by the Department of conveyance, plants, plant products, and Agriculture. other products and articles from Guam 319.8–21 Release of cotton and covers after into or through any other State, Terri- 18 months’ storage. 319.8–22 Ports of entry or export. tory, or District is also regulated by 319.8–23 Treatment. part 330 of this chapter. 319.8–24 Collection and disposal of waste. 319.8–25 Costs and charges. § 318.82–3 Costs. 319.8–26 Material refused entry. All costs incident to the inspection, handling, cleaning, safeguarding, treat- Subpart—Sugarcane ing, or other disposal of products or ar- 319.15 Notice of quarantine. ticles under this subpart, except for the 319.15a Administrative instructions and in- services of an inspector during regu- terpretation relating to entry into Guam larly assigned hours of duty and at the of bagasse and related sugarcane prod- usual places of duty, shall be borne by ucts. the owner. Subpart—Citrus Canker and Other Citrus PART 319—FOREIGN QUARANTINE Diseases NOTICES 319.19 Notice of quarantine. Subpart—Foreign Cotton and Covers Subpart—Corn Diseases QUARANTINE QUARANTINE Sec. 319.24 Notice of quarantine. 319.8 Notice of quarantine. 319.24a Administrative instructions relating 319.8a Administrative instructions relating to entry of corn into Guam. to the entry of cotton and covers into Guam. REGULATIONS GOVERNING ENTRY OF INDIAN CORN OR MAIZE REGULATIONS; GENERAL 319.24–1 Applications for permits for impor- 319.8–1 Definitions. -

Article 1. General Provisions

Article 1. General Provisions ― 1 ― Article 1. General Provisions 1. General Principles This Food Code shall be principally interpreted and applied by general provisions, except as otherwise specified. 1) This Food Code contains the following items. (1) Standard about methods of manufacturing, processing, using, cooking, storing foods and specification about food components under the regulations of Paragraph 1 in Article 7 of Food Sanitation Act. (2) Standard about manufacturing methods of utensil, container, packaging and specification about utensil, container, packaging and their raw materials under the regulations of Paragraph 1 in Article 9 of Food Sanitation Act. (3) Labeling standard about food, food additives, utensil, container, packaging and GMO under the regulations of Paragraph 1 in Article 10 of Food Sanitation Act. 2) Weights and measures shall be applied by the metric system and are indicated in following codes. (1) Length : m, cm, mm,μ m, nm (2)Volume:L,mL,μ L (3)Weight : kg, g, mg,μ g, ng, pg (4) Area : cm 2 (5) Calorie : kcal, kj 3) Weight percentage is indicated with the symbol of %. However, material content (g) in 100 mL solution is indicated with w/v% and material content (mL) in 100 mL solution with v/v%. Weight parts per million may be indicated with the symbol of mg/kg, ppm, or mg/L. 4) Temperature indication adopts Celsius(℃ ) type. 5) Standard temperature is defined as 20℃ , and ordinary temperature as 15~25 ℃ , and room temperature as 1~3 5℃ , and slightly warm temperature as 30~40℃ . 6) Except as otherwise specified, cold water is defined as waterof15℃ orlower,hotwater aswaterof60~70 ℃ , boiling water as water of about 100℃ , and heating temperature "in/under water bath" is, except as otherwise specified, defined as about 100℃ and water bath can be replaced with steam bath of about 100℃ . -

Comparative Morphology and Anatomy of Non-Rheophytic and Rheophytic Types of Adenophora Triphylla Var

American Journal of Plant Sciences, 2012, 3, 805-809 805 http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ajps.2012.36097 Published Online June 2012 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ajps) Comparative Morphology and Anatomy of Non-Rheophytic and Rheophytic Types of Adenophora triphylla var. japonica (Campanulaceae) Kyohei Ohga1, Miwako Muroi1, Hiroshi Hayakawa1, Jun Yokoyama2, Katsura Ito1, Shin-Ichi Tebayashi1, Ryo Arakawa1, Tatsuya Fukuda1* 1Faculty of Agriculture, Kochi University, Kochi, Japan; 2Faculty of Science, Yamagata University, Yamagata, Japan. Email: [email protected] Received April 10th, 2012; revised April 30th, 2012; accepted May 18th, 2012 ABSTRACT The morphology and anatomy of leaves of rheophytic and non-rheophytic types of Adenophora triphylla (Thunb.) ADC var. japonica (Regel) H. Hara were compared in order to clarify how leaf characteristics differ. Our results revealed that the leaf of the rheophytic type of A. triphylla var. japonica was narrower than the leaf of the non-rheophytic type be- cause of fewer cells that were also smaller. Moreover, surprisingly, the rheophytic ecotype of A. triphylla var. japonica was thinner than that of the non-rheophytic type, although the general tendency is that the rheophytic leaf is thicker than the closely related non-rheophytic species, suggesting that the rheophytic type of A. triphylla var. japonica adapts dif- ferently, as compared to other rheophytic plants, to solar radiation and evaporation. Keywords: Rheophyte; Leaf; Ecotype; Adenophora triphylla var. japonica 1. Introduction leaf modification from fern to angiosperm (Osmunda lancea Thunb. (Osmundaceae): [5]; Aster microcephalus (Miq.) Morphological diversity is a special feature of angios- Franch. et Sav. var. ripensis Makino (Asteraceae): [6]; perms, and a key challenge in biology is to understand Dendranthema yoshinaganthum Makino ex Kitam. -

Global Survey of Ex Situ Betulaceae Collections Global Survey of Ex Situ Betulaceae Collections

Global Survey of Ex situ Betulaceae Collections Global Survey of Ex situ Betulaceae Collections By Emily Beech, Kirsty Shaw and Meirion Jones June 2015 Recommended citation: Beech, E., Shaw, K., & Jones, M. 2015. Global Survey of Ex situ Betulaceae Collections. BGCI. Acknowledgements BGCI gratefully acknowledges the many botanic gardens around the world that have contributed data to this survey (a full list of contributing gardens is provided in Annex 2). BGCI would also like to acknowledge the assistance of the following organisations in the promotion of the survey and the collection of data, including the Royal Botanic Gardens Edinburgh, Yorkshire Arboretum, University of Liverpool Ness Botanic Gardens, and Stone Lane Gardens & Arboretum (U.K.), and the Morton Arboretum (U.S.A). We would also like to thank contributors to The Red List of Betulaceae, which was a precursor to this ex situ survey. BOTANIC GARDENS CONSERVATION INTERNATIONAL (BGCI) BGCI is a membership organization linking botanic gardens is over 100 countries in a shared commitment to biodiversity conservation, sustainable use and environmental education. BGCI aims to mobilize botanic gardens and work with partners to secure plant diversity for the well-being of people and the planet. BGCI provides the Secretariat for the IUCN/SSC Global Tree Specialist Group. www.bgci.org FAUNA & FLORA INTERNATIONAL (FFI) FFI, founded in 1903 and the world’s oldest international conservation organization, acts to conserve threatened species and ecosystems worldwide, choosing solutions that are sustainable, based on sound science and take account of human needs. www.fauna-flora.org GLOBAL TREES CAMPAIGN (GTC) GTC is undertaken through a partnership between BGCI and FFI, working with a wide range of other organisations around the world, to save the world’s most threated trees and the habitats which they grow through the provision of information, delivery of conservation action and support for sustainable use. -

Nuclear and Plastid DNA Phylogeny of the Tribe Cardueae (Compositae

1 Nuclear and plastid DNA phylogeny of the tribe Cardueae 2 (Compositae) with Hyb-Seq data: A new subtribal classification and a 3 temporal framework for the origin of the tribe and the subtribes 4 5 Sonia Herrando-Morairaa,*, Juan Antonio Callejab, Mercè Galbany-Casalsb, Núria Garcia-Jacasa, Jian- 6 Quan Liuc, Javier López-Alvaradob, Jordi López-Pujola, Jennifer R. Mandeld, Noemí Montes-Morenoa, 7 Cristina Roquetb,e, Llorenç Sáezb, Alexander Sennikovf, Alfonso Susannaa, Roser Vilatersanaa 8 9 a Botanic Institute of Barcelona (IBB, CSIC-ICUB), Pg. del Migdia, s.n., 08038 Barcelona, Spain 10 b Systematics and Evolution of Vascular Plants (UAB) – Associated Unit to CSIC, Departament de 11 Biologia Animal, Biologia Vegetal i Ecologia, Facultat de Biociències, Universitat Autònoma de 12 Barcelona, ES-08193 Bellaterra, Spain 13 c Key Laboratory for Bio-Resources and Eco-Environment, College of Life Sciences, Sichuan University, 14 Chengdu, China 15 d Department of Biological Sciences, University of Memphis, Memphis, TN 38152, USA 16 e Univ. Grenoble Alpes, Univ. Savoie Mont Blanc, CNRS, LECA (Laboratoire d’Ecologie Alpine), FR- 17 38000 Grenoble, France 18 f Botanical Museum, Finnish Museum of Natural History, PO Box 7, FI-00014 University of Helsinki, 19 Finland; and Herbarium, Komarov Botanical Institute of Russian Academy of Sciences, Prof. Popov str. 20 2, 197376 St. Petersburg, Russia 21 22 *Corresponding author at: Botanic Institute of Barcelona (IBB, CSIC-ICUB), Pg. del Migdia, s. n., ES- 23 08038 Barcelona, Spain. E-mail address: [email protected] (S. Herrando-Moraira). 24 25 Abstract 26 Classification of the tribe Cardueae in natural subtribes has always been a challenge due to the lack of 27 support of some critical branches in previous phylogenies based on traditional Sanger markers.