Urban Population Data 1801-1911

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geography, Background Information, Civil Parishes and Islands

Geography – Background Information – Civil Parishes and Islands Civil Parishes Geography Branch first began plotting postcode boundaries in 1973. In addition to the creation of postcode boundaries, Geography Branch also assigned each postcode to an array of Scottish boundary datasets including civil parish boundaries. From 1845 to 1930, civil parishes formed part of Scotland’s local government system. The parishes, which had their origins in the ecclesiastical parishes of the Church of Scotland, often overlapped the then existing county boundaries, largely because they reflected earlier territorial divisions. Parishes have had no direct administrative function in Scotland since 1930. In 1930, all parishes were grouped into elected district councils. These districts were abolished in 1975, and the new local authorities established in that year often cut across civil parish boundaries. In 1996, there was a further re-organisation of Scottish local government, and a number of civil parishes now lie in two or more council areas. There are 871 civil parishes in Scotland. The civil parish boundary dataset is the responsibility of Geography Branch. The initial version of the boundaries was first created in the mid-1960s. The boundaries were plotted on to Ordnance Survey 1:10,000 maps using the written descriptions of the parishes. In the late 1980s Geography Branch introduced a Geographic Information System (called ‘GenaMap’) to its working practices. At this point the manually-plotted civil parish boundaries were digitised using the GenaMap system. In 2006, GenaMap was replaced by ESRI’s ArcGIS product, and the civil parish boundaries were migrated to the new system. At this stage, the Ordnance Survey digital product MasterMap was made available as the background map for Geography Branch’s digitising requirements. -

Thanington Without Civil Parish and Council As Seen

THANINGTON WITHOUT CIVIL PARISH AND COUNCIL AS SEEN FROM THEIR MINUTE BOOKS 1894-1994 - AN INITIAL ASSESSMENT By Clive. H. Church ‘Rufflands’ 72A New House Lane, Canterbury CT 4 7BJ 01227-458437 07950-666488 [email protected] Originally posted on the website of Thanington Without Civil Parish Council on 4 April 2005 in PDF and HMTL versions. Subsequently updated and illustrated in 2014. For the original see http://www.thanington-pc.gov.uk/pchistory/history.html 1 THANINGTON WITHOUT CIVIL PARISH AND COUNCIL, AS SEEN FROM THEIR MINUTE BOOKS, 1894-1994 Tracing the development of a parish and its council is not easy. Neither constituents nor historians pay them much attention. Despite its importance in the past, local government is not now well regarded thanks to the centralization and mediaization of British political culture. Moreover, although there are many sources, including the recollections of parishioners, they are often not easily available. And memories are often fallible. However, we can get some way towards understanding them through their minute books. For, while these are far from complete records, they do allow us an insight into the organization and attitudes of a council as it emerged from the changing pattern of local government in England. For civil parishes have never been able to decide their own organization. This has been laid down by national legislation. In other words, they are creatures of Parliament. In the case of Thanington Without the minute books allow us to trace the evolution of both the original Parish Meeting and its successor and, after 1935, of the Parish Council itself. -

Foi Publishing Template

Freedom of Information Act Request Reference: F15/0323 Response Date: 21 December 2015 Thank you for your request for information. Your original request to Maldon District Council has been replicated below, together with the Council’s response: In accordance with the provisions of the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) 2000, I would like to make a formal request for the information set out below in relation to your local authority area (Maldon District Council). Civil parishes 1. Are there civil parishes in your local authority area? 2. If yes, is the entirety of your local authority area parished? 3. For each of parished parts of your local authority area, please provide the following information: a. The name of the civil parish. b. Whether it has a parish council or a parish meeting. c. Whether it is a precepting, group precepting, or non-precepting authority in the current financial year. d. If it has a parish council, what style (if any) does it have i.e. parish, town, community, village or city council? e. Elections: when, by year, (i) did they last take place, and (ii) are they next due to take place? (Please advise dates even if uncontested.) f. Are there individual (plural) wards within the parish, or is the whole parish one ward for the purposes of electing councillors? 4. If parts of your local authority area are unparished, please provide the following information in relation to each part: a. The name of the area which is unparished (i.e. name of town / village / community). b. Whether there is an established community forum (or similar) recognised by your local authority, for consultations etc. -

Edinburgh Research Explorer

Edinburgh Research Explorer Getting involved in plan-making Citation for published version: Brookfield, K 2016, 'Getting involved in plan-making: Participation in neighbourhood planning in England', Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, vol. 35, no. 3, pp. 397–416. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263774X16664518 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1177/0263774X16664518 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 30. Sep. 2021 Getting involved in plan-making: participation in neighbourhood planning in England Abstract Neighbourhood planning, introduced through the Localism Act 2011, was intended to provide communities in England with new opportunities to plan and manage development. All communities were presented as being readily able to participate in this new regime with Ministers declaring it perfectly conceived to encourage greater involvement from a wider range of people. Set against such claims, whilst addressing significant gaps in the evidence, this paper provides a critical review of participation in neighbourhood planning, supported by original empirical evidence drawn from case study research. -

Parish' and 'City' -- a Shifting Identity: Salisbury 1440-1600

Early Theatre 6.1(2003) audrey douglas ‘Parish’ and ‘City’ – A Shifting Identity: Salisbury 1440–1600 The study and documentation of ceremony and ritual, a broad concern of Records of Early English Drama, has stimulated discussion about their purpose and function in an urban context. Briefly, in academic estimation their role is largely positive, both in shaping civic consciousness and in harmonizing diverse classes and interests while – as a convenient corollary – simultaneously con- firming local hierarchies. Profitable self-promotion is also part of this urban picture, since ceremony and entertainment, like seasonal fairs, potentially attracted interest from outside the immediate locality. There are, however, factors that compromise this overall picture of useful urban concord: the dominance of an urban elite, for instance, may effectually be stabilized, promoted, or even disguised by ceremony and ritual; on the other hand, margi- nalized groups (women and the poor) have normally no place in them at all.l Those excluded from participation in civic ritual and ceremonial might, nevertheless, be to some extent accommodated in the pre-Reformation infra- structure of trade guilds and religious guilds. Both organizational groups crossed social and economic boundaries to draw male and female members together in ritual and public expression of a common purpose and brotherhood – signalling again (in customary obit, procession, and feasting) harmony and exclusivity, themes with which, it seems, pre-Reformation urban life was preoccupied. But although women were welcome within guild ranks, office was normally denied them. Fifteenth-century religious guilds also saw a decline in membership drawn from the poorer members of society, with an overall tendency for a dominant guild to become identified with a governing urban elite.2 Less obvious perhaps, but of prime importance to those excluded from any of the above, was the parish church itself, whose round of worship afforded forms of ritual open to all. -

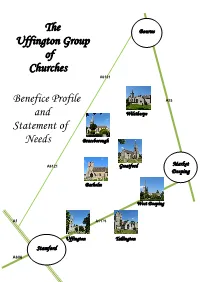

The Uffington Group of Churches Benefice Profile and Statement Of

The Bourne Uffington Group of Churches A6121 Benefice Profile A15 and Wilsthorpe Statement of Needs Braceborough A6121 Greatford Market Deeping Barholm West Deeping A1 A1175 Uffington Tallington Stamford A606 Introduction Thank you for taking an interest in the Uffington Group of Churches. If you are reading this to see whether you might be interested in becoming our next Rector, we hope you will find it helpful. If you are reading this for any other reason, we hope you will find this profile interesting, and if you are in the area, or might just be passing through, we hope that you might wish to come and see us. We hope that our new Rector will be able to inspire us in three key areas of our discipleship growth plans: drawing more of our villagers, especially from the missing generations, to respond to the message of the gospel (ie making more Christ-like Christians, as Bishop Edward King might have said); enhancing the faith of current members of our congregations (responding to the need for more Christ-like Christians, as Bishop Edward King did say); ensuring that our seven churches are not only kept open and functioning, but are made more attractive focal points for the lives of our parishioners and communities. We believe that such a person is likely to be: someone who will prayerfully seek to preach, teach and share scriptural truth; willing to grasp the nature of rural ministry; able to preserve the identity of each parish while maintaining coherence of the Group; comfortable with a range of worship and broad expression of faith; able to develop and communicate an inspirational vision for building God’s work amongst all ages in the Group and in each parish; able to lead, cultivate and enthuse teams of volunteers involved in the ministry, administration and upkeep of the seven churches; open, approachable and supportive, and willing to be visible at community events in all the villages; keen to guide and support the Christian ethos of the Uffington Church of England Primary School, being a regular visitor to the school and ex-officio governor. -

Researching Irish and Scots-Irish Ancestors an INTRODUCTION to the SOURCES and the ARCHIVES

Researching Irish and Scots-Irish Ancestors AN INTRODUCTION TO THE SOURCES AND THE ARCHIVES Ulster Historical Foundation Charity Registration No. NIC100280 Interest in researching Irish ancestors has never been greater. Given Ireland’s history of emigration, it is hardly surprising to find that around the world tens of millions of people have a family connection with the island. Much of this interest comes from Britain, the USA, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. What follows is a very basic introduction to researching Irish ancestors. It highlights what the major sources are and where they can be found. Prior to 1922 Ireland was under one jurisdiction and so where we refer to Ireland we mean the entire island. Where we are referring specifically to Northern Ireland or the Republic of Ireland we will try to make this clear. SOME BACKGROUND INFORMATION Exploding a myth an elderly person’s reminiscences prove to be an accurate A popular misconception about researching Irish ancestors is recollection of the facts. A family Bible is another possible that it is a fruitless exercise because so many records were source of information on your ancestors. Gathering this destroyed. There is no denying that the loss of so many information before you visit the archives can save a great deal records in the destruction of the Public Record Office, of time. Once you find out what you do know you will then Dublin, in 1922 was a catastrophe as far as historical and be aware of the gaps and will have a clearer idea of what you genealogical research is concerned. -

Parish Register Guide Entries for Painswick, Harescombe, Haresfield, Brookthorpe

East Dean ............................................................................................................................................................................................3 Eastington (Near Northleach) ...............................................................................................................................................................5 Eastington, Nr Stonehouse (St Michael) ..............................................................................................................................................7 Eastleach .............................................................................................................................................................................................9 Eastleach Martin (St Mary) ................................................................................................................................................................. 11 Eastleach Turville (St Andrew) ........................................................................................................................................................... 13 Ebrington (St Ethelburga) ................................................................................................................................................................... 15 Edge (St John the Baptist) ................................................................................................................................................................. 17 Edgeworth (St Mary) -

The Role and Effectiveness of Parish Councils in Gloucestershire

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by University of Worcester Research and Publications The Role and Effectiveness of Parish Councils in Gloucestershire: Adapting to New Modes of Rural Community Governance Nicholas John Bennett Coventry University and University of Worcester April 2006 Thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Philosophy 2 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER TITLE PAGE NO. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 8 ABSTRACT 9 1 INTRODUCTION – Research Context, Research Aims, 11 Thesis Structure 2 LITERATURE REVIEW I: RURAL GOVERNANCE 17 Section 2.1: Definition & Chronology 17 Section 2.2 : Theories of Rural Governance 27 3 LITERATURE REVIEW II: RURAL GOVERNANCE 37 Section 3.1: The Role & Nature of Partnerships 37 Section 3.2 : Exploring the Rural White Paper 45 Section 3.3 : The Future Discourse for Rural Governance 58 Research 4 PARISH COUNCILS IN ENGLAND/INTRODUCTION TO 68 STUDY REGION 5 METHODOLOGY 93 6 COMPOSITION & VIBRANCY OF PARISH COUNCILS 106 IN GLOUCESTERSHIRE 7 ISSUES & PRIORITIES FOR PARISH COUNCILS 120 8 PARISH COUNCILS - ROLES, NEEDS & CONFLICTS 138 9 CONCLUSIONS 169 BIBLIOGRAPHY 190 ANNEXES 1 Copy of Parish Council Postal Questionnaire 200 2 Parish Council Clerk Interview Sheet & Observation Data 210 Capture Sheet 3 Listing of 262 Parish Councils in the administrative 214 county of Gloucestershire surveyed (Bolded parishes indicate those who responded to survey) 4 Sample population used for Pilot Exercise 217 5 Listing of 10 Selected Case Study Parish Councils for 218 further observation, parish clerk interviews & attendance at Parish Council Meetings 4 LIST OF MAPS, TABLES & FIGURES MAPS TITLE PAGE NO. -

Year Surname Age Born Sx Relationstataddress Civil Parish

Year Surname Age Born Sx Relation StatAddress Civil parish CTY Birthplace Occupation Notes PIN Serial Birth places & occupations in blue 1911 census taken from 1901 census 1841 STRONACH George 15 1826 M Servant Auchinhove,Auchterless Auchterless ABD Scotland farm labourer G115 10001 1841 STRONACH Alexander 30 1811 M Head M Lower Denburn,Old Machar Bon Accord ABD Scotland labourer A139 10002 1841 STRONACH Elizabeth (X) 28 1813 F Wife M Lower Denburn,Old Machar Bon Accord ABD Scotland E020 10003 1841 STRONACH Francis 14 1827 M Lower Denburn,Old Machar Bon Accord ABD Scotland F107 10004 1841 STRONACH Janet 12 1829 F Lower Denburn,Old Machar Bon Accord ABD Scotland J289 10005 1841 STRONACH Ann 6 1835 F Lower Denburn,Old Machar Bon Accord ABD Scotland A411 10006 1841 STRONACH Christian 2 1839 F Lower Denburn,Old Machar Bon Accord ABD Scotland C203 10007 1841 STRONACH Robert 62 1779 M Head M Windmill Brae,Old Machar Bon Accord ABD Scotland labourer R101 10008 1841 STRONACH Barbara (ROSS) 49 1792 F Wife M Windmill Brae,Old Machar Bon Accord ABD Scotland B107 10009 1841 STRONACH Janet 19 1822 F Daughter Windmill Brae,Old Machar Bon Accord ABD Scotland J267 10010 1841 STRONACH Barbara 13 1828 F Daughter Windmill Brae,Old Machar Bon Accord ABD Scotland B115 10011 1841 STRONACH Ann 9 1832 F Daughter Windmill Brae,Old Machar Bon Accord ABD Scotland A401 10012 1841 STRONACH George 20 1821 M Servant Meikle Newton,Clatt Clatt ABD Aberdeenshire farm labourer G113 10013 1841 STRONACH Alexander 25 1816 M Servant Easter Anchmenzie Clatt ABD Glass, Aberdeenshire -

Battle Civil Parish

Battle Civil Parish Neighbourhood Plan 2019-2028 PLAN PROPOSAL SUBMISSION Published by Battle Town Council for the Regulation 15 Plan Proposal Submission under the Neighbourhood Planning (General) Regulations 2012 and in accordance with EU Directive 2001/42 NOVEMBER 2020 Table of Contents FOREWORD 4 SECTION 1: Introduction and Background 5 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Neighbourhood Area 1.3 The Planning Policy Context SECTION 2: Process Summary 9 2.1 The Plan Process 2.2 Community Engagement 2.3 Evidence Base Overview SECTION 3: The Parish background 11 3.1 Spatial Characteristics of the Parish 3.2 Economy 3.3 Population and households 3.4 Households 3.5 Transport 3.6 Conservation Area 3.7 Development from an Historic Perspective – The Town of Battle 3.8 Facilities and Services 3.9 Constraints 3.10 SWOT Analysis of Battle SECTION 4: Vision and Objectives 35 4.1 Vision 4.2 Objectives SECTION 5: Neighbourhood Plan Policies 38 5.1 Housing and Development 5.2 Infrastructure 5.3 Environment 5.4 Economy and Tourism SECTION 6: Implementation, Monitoring and Review 60 SECTION 7: Community Aspirations 61 For purposes of this Plan the use of appendix, annexe and schedule are used as follows: An appendix is included at the end of the plan because it is too large for the body of the plan but needs to be referenced for clarity. The aim of the appendices is to add greater details, visuals and aid for better understanding. An annexe is a standalone document/report which can be read in its own right but supports the main document. -

St Albans the Urban Area of St Albans, Sandridge Civil Parish and Part Of

St Albans The urban area of St Albans, Sandridge Civil Parish and part of the Civil Parishes of St Michael and Colney Heath in the District of St Albans and within the boundaries given below. North: The northern boundary is defined by the meeting of St Albans with Redbourn and Wheathampstead Civil Parish boundaries. It takes the following route:- From the River Ver due east of Punchbowl Lane a line to Horse and Jockey Farm , passing immediately north of Childwick Stud. South on the Harpenden Road to Ayre’s End Lane, and from the south side of the Lane, east to the junction of Sandridge Road (B651) and Dyke Lane, skirting north of Pismire Spring, Pudler’s Wood and Round Wood. Dyke Lane, Beech-Hyde Farm and a line to Sandridge Civil Parish boundary at Colman Green Spring. East: Samdridge and Colney Heath Civil Parish boundaries from Coleman Green to the North Orbital Road (A405). South: From Sleapshyde Farm on the Colney Heath C.P. boundary, the A405 to the link road with Tyttenhanger Lane, Highfield Lane and Hill End Lane to the London Road (A1081). London Road and Milehouse Lane to the north end of Cottonmill Lane; the footpath across the Golf Course northwest to near the end of Riverside Road, then southwest to pass between Boleyn Drive and Monks Close to the railway. The railway to Abbey Station. West: From Abbey Station, Holywell Hill to the River Ver, the Ver to Bluehouse Hill, then Redbourn Road to Bow Bridge. The River Ver from Bow Bridge to due east of Punch Bowl Lane.