The Parish Map

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

City of Manhattan Voting Precincts

R i v R o e c r k y B F e C o n i r A B C D E F G H I r d d J K L M N 3rd Pl L8 Colgate Ter G9 Hanly St L4 Margot Ln G5 Princeton Pl F9 Tex Winter Dr H5 R A College Ave H5 Harahey Rdg F2 Marion Ave G2 Pullman Lndg D6 Thackrey St I8 H d o Abbey Cir E3 College Heights Cir H7 Harland Dr B8 Marlatt Ave D1/G2 Purcells Mill K4 Thomas Cir K6 ll ow Tree Abbott Cir D4 College Heights Rd I7 Harris Ave I7 Marque Hill Rd F1 Purple Aster Pl B5 Thurston St K7 Rd Ln ell Adams St N9 College View Rd H7 Harry Rd I6 Mary Kendal Ct F4 Q Tiana Ter G4 urc P Faith Evangelical Agriculture Rd I4 Collins Ln J12 Hartford Rd H6 Matter Dr K2 Quivera Cir I7 Timberlane Dr G7 CITY OF MANHATTAN VOTING PRECINCTS Agronomy Central Rd H4 Colorado St K9 Hartman Pl H6 Max Cir E11 Quivera Dr I7 Timberwick Pl F8 Top Of the Free Church Agronomy Farm Rd H4 Columbine Ct N5 Harvard Pl F9 McCain Ln K6 R Tobacco Cir B4 World Dr k Agronomy Field Rd H4 Commons Pl G10 Harvey Cir N5 McCall Pl M7 Rangeview Ln B4 Tobacco Rd B4 Airport Rd A12 Concord Cir D5 Harvey Dr M5 McCall Rd N7 Ranser Rd G5 Todd Rd H6 Valleydale Shady C 1 n 1 V a L Dr Valley Dr se Alabama Ln F5 Concord Ln D5 Haustead Ct B8 McCollum St I7 Raspberry Cir M4 Tomahawk Cir F2 Hill Valley Dr a m d en l t R Alecia Dr G2 Conley Cir F11 Haventon Ct A8 McCullough Pl N7 Raspberry Dr M4 Tonga St F12 n le d o G1 y M1 Allen Rd L5 Connecticut Ave G7 Haventon Dr A8 McDowell Ave F4 Ratone Ln L7 Travers Dr B2 p Green Valle y w A1 B1 C1 D1 w E1 F1 H1 I1 ood K1 L1 N1 Allison Ave G11 Conrow Dr F6 Hawthorne Wds Cir E4 Meade Cir G4 Ratone -

Geography, Background Information, Civil Parishes and Islands

Geography – Background Information – Civil Parishes and Islands Civil Parishes Geography Branch first began plotting postcode boundaries in 1973. In addition to the creation of postcode boundaries, Geography Branch also assigned each postcode to an array of Scottish boundary datasets including civil parish boundaries. From 1845 to 1930, civil parishes formed part of Scotland’s local government system. The parishes, which had their origins in the ecclesiastical parishes of the Church of Scotland, often overlapped the then existing county boundaries, largely because they reflected earlier territorial divisions. Parishes have had no direct administrative function in Scotland since 1930. In 1930, all parishes were grouped into elected district councils. These districts were abolished in 1975, and the new local authorities established in that year often cut across civil parish boundaries. In 1996, there was a further re-organisation of Scottish local government, and a number of civil parishes now lie in two or more council areas. There are 871 civil parishes in Scotland. The civil parish boundary dataset is the responsibility of Geography Branch. The initial version of the boundaries was first created in the mid-1960s. The boundaries were plotted on to Ordnance Survey 1:10,000 maps using the written descriptions of the parishes. In the late 1980s Geography Branch introduced a Geographic Information System (called ‘GenaMap’) to its working practices. At this point the manually-plotted civil parish boundaries were digitised using the GenaMap system. In 2006, GenaMap was replaced by ESRI’s ArcGIS product, and the civil parish boundaries were migrated to the new system. At this stage, the Ordnance Survey digital product MasterMap was made available as the background map for Geography Branch’s digitising requirements. -

Thanington Without Civil Parish and Council As Seen

THANINGTON WITHOUT CIVIL PARISH AND COUNCIL AS SEEN FROM THEIR MINUTE BOOKS 1894-1994 - AN INITIAL ASSESSMENT By Clive. H. Church ‘Rufflands’ 72A New House Lane, Canterbury CT 4 7BJ 01227-458437 07950-666488 [email protected] Originally posted on the website of Thanington Without Civil Parish Council on 4 April 2005 in PDF and HMTL versions. Subsequently updated and illustrated in 2014. For the original see http://www.thanington-pc.gov.uk/pchistory/history.html 1 THANINGTON WITHOUT CIVIL PARISH AND COUNCIL, AS SEEN FROM THEIR MINUTE BOOKS, 1894-1994 Tracing the development of a parish and its council is not easy. Neither constituents nor historians pay them much attention. Despite its importance in the past, local government is not now well regarded thanks to the centralization and mediaization of British political culture. Moreover, although there are many sources, including the recollections of parishioners, they are often not easily available. And memories are often fallible. However, we can get some way towards understanding them through their minute books. For, while these are far from complete records, they do allow us an insight into the organization and attitudes of a council as it emerged from the changing pattern of local government in England. For civil parishes have never been able to decide their own organization. This has been laid down by national legislation. In other words, they are creatures of Parliament. In the case of Thanington Without the minute books allow us to trace the evolution of both the original Parish Meeting and its successor and, after 1935, of the Parish Council itself. -

The Medieval English Borough

THE MEDIEVAL ENGLISH BOROUGH STUDIES ON ITS ORIGINS AND CONSTITUTIONAL HISTORY BY JAMES TAIT, D.LITT., LITT.D., F.B.A. Honorary Professor of the University MANCHESTER UNIVERSITY PRESS 0 1936 MANCHESTER UNIVERSITY PRESS Published by the University of Manchester at THEUNIVERSITY PRESS 3 16-324 Oxford Road, Manchester 13 PREFACE its sub-title indicates, this book makes no claim to be the long overdue history of the English borough in the Middle Ages. Just over a hundred years ago Mr. Serjeant Mere- wether and Mr. Stephens had The History of the Boroughs Municipal Corporations of the United Kingdom, in three volumes, ready to celebrate the sweeping away of the medieval system by the Municipal Corporation Act of 1835. It was hardly to be expected, however, that this feat of bookmaking, good as it was for its time, would prove definitive. It may seem more surprising that the centenary of that great change finds the gap still unfilled. For half a century Merewether and Stephens' work, sharing, as it did, the current exaggera- tion of early "democracy" in England, stood in the way. Such revision as was attempted followed a false trail and it was not until, in the last decade or so of the century, the researches of Gross, Maitland, Mary Bateson and others threw a fiood of new light upon early urban development in this country, that a fair prospect of a more adequate history of the English borough came in sight. Unfortunately, these hopes were indefinitely deferred by the early death of nearly all the leaders in these investigations. -

Foi Publishing Template

Freedom of Information Act Request Reference: F15/0323 Response Date: 21 December 2015 Thank you for your request for information. Your original request to Maldon District Council has been replicated below, together with the Council’s response: In accordance with the provisions of the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) 2000, I would like to make a formal request for the information set out below in relation to your local authority area (Maldon District Council). Civil parishes 1. Are there civil parishes in your local authority area? 2. If yes, is the entirety of your local authority area parished? 3. For each of parished parts of your local authority area, please provide the following information: a. The name of the civil parish. b. Whether it has a parish council or a parish meeting. c. Whether it is a precepting, group precepting, or non-precepting authority in the current financial year. d. If it has a parish council, what style (if any) does it have i.e. parish, town, community, village or city council? e. Elections: when, by year, (i) did they last take place, and (ii) are they next due to take place? (Please advise dates even if uncontested.) f. Are there individual (plural) wards within the parish, or is the whole parish one ward for the purposes of electing councillors? 4. If parts of your local authority area are unparished, please provide the following information in relation to each part: a. The name of the area which is unparished (i.e. name of town / village / community). b. Whether there is an established community forum (or similar) recognised by your local authority, for consultations etc. -

Edinburgh Research Explorer

Edinburgh Research Explorer Getting involved in plan-making Citation for published version: Brookfield, K 2016, 'Getting involved in plan-making: Participation in neighbourhood planning in England', Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, vol. 35, no. 3, pp. 397–416. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263774X16664518 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1177/0263774X16664518 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 30. Sep. 2021 Getting involved in plan-making: participation in neighbourhood planning in England Abstract Neighbourhood planning, introduced through the Localism Act 2011, was intended to provide communities in England with new opportunities to plan and manage development. All communities were presented as being readily able to participate in this new regime with Ministers declaring it perfectly conceived to encourage greater involvement from a wider range of people. Set against such claims, whilst addressing significant gaps in the evidence, this paper provides a critical review of participation in neighbourhood planning, supported by original empirical evidence drawn from case study research. -

Parish' and 'City' -- a Shifting Identity: Salisbury 1440-1600

Early Theatre 6.1(2003) audrey douglas ‘Parish’ and ‘City’ – A Shifting Identity: Salisbury 1440–1600 The study and documentation of ceremony and ritual, a broad concern of Records of Early English Drama, has stimulated discussion about their purpose and function in an urban context. Briefly, in academic estimation their role is largely positive, both in shaping civic consciousness and in harmonizing diverse classes and interests while – as a convenient corollary – simultaneously con- firming local hierarchies. Profitable self-promotion is also part of this urban picture, since ceremony and entertainment, like seasonal fairs, potentially attracted interest from outside the immediate locality. There are, however, factors that compromise this overall picture of useful urban concord: the dominance of an urban elite, for instance, may effectually be stabilized, promoted, or even disguised by ceremony and ritual; on the other hand, margi- nalized groups (women and the poor) have normally no place in them at all.l Those excluded from participation in civic ritual and ceremonial might, nevertheless, be to some extent accommodated in the pre-Reformation infra- structure of trade guilds and religious guilds. Both organizational groups crossed social and economic boundaries to draw male and female members together in ritual and public expression of a common purpose and brotherhood – signalling again (in customary obit, procession, and feasting) harmony and exclusivity, themes with which, it seems, pre-Reformation urban life was preoccupied. But although women were welcome within guild ranks, office was normally denied them. Fifteenth-century religious guilds also saw a decline in membership drawn from the poorer members of society, with an overall tendency for a dominant guild to become identified with a governing urban elite.2 Less obvious perhaps, but of prime importance to those excluded from any of the above, was the parish church itself, whose round of worship afforded forms of ritual open to all. -

Appendix-D Methodology of Standardised Acceptance Rates

Appendix D: Methodology of standardised acceptance rates calculation and administrative area geography and Registry population groups in England & Wales Chapter 4, on the incidence of new patients, includes Greater London is subdivided into the London an analysis of standardised acceptance rates in Eng- Boroughs and the City of London. land & Wales for areas covered by the Registry. The methodology is described below. This methodology is also used in Chapter 5 for analysis of prevalent Unitary Authorities patients. Table D.1: Unitary Authorities Code UA name Patients 00EB Hartlepool 00EC Middlesbrough All new cases accepted onto RRT in each year 00EE Redcar and Cleveland recorded by the Registry were included. Each 00EF Stockton-on-Tees patient’s postcode was matched to a 2001 Census 00EH Darlington output area. In 2003 there were only 14 patients 00ET Halton with postcodes that had no match; there was no 00EU Warrington obvious clustering by renal unit. 00EX Blackburn with Darwen 00EY Blackpool Geography: Unitary 00FA Kingston upon Hull, City of Authorities, Counties and other 00FB East Riding of Yorkshire 00FC North East Lincolnshire areas 00FD North Lincolnshire 00FF York In contrast to 2002 contiguous ‘county’ areas were 00FK Derby not derived by merging Unitary Authorities (UAs) 00FN Leicester with a bordering county. For example, Southampton 00FP Rutland UA and Portsmouth UA were kept separate from 00FY Nottingham Hampshire county. The final areas used were Metro- 00GA Herefordshire, County of politan counties, Greater London districts, Welsh 00GF Telford and Wrekin areas, Shire counties and Unitary Authorities – these 00GL Stoke-on-Trent different types of area were called ‘Local Authority 00KF Southend-on-Sea (LA) areas’. -

English Hundred-Names

l LUNDS UNIVERSITETS ARSSKRIFT. N. F. Avd. 1. Bd 30. Nr 1. ,~ ,j .11 . i ~ .l i THE jl; ENGLISH HUNDRED-NAMES BY oL 0 f S. AND ER SON , LUND PHINTED BY HAKAN DHLSSON I 934 The English Hundred-Names xvn It does not fall within the scope of the present study to enter on the details of the theories advanced; there are points that are still controversial, and some aspects of the question may repay further study. It is hoped that the etymological investigation of the hundred-names undertaken in the following pages will, Introduction. when completed, furnish a starting-point for the discussion of some of the problems connected with the origin of the hundred. 1. Scope and Aim. Terminology Discussed. The following chapters will be devoted to the discussion of some The local divisions known as hundreds though now practi aspects of the system as actually in existence, which have some cally obsolete played an important part in judicial administration bearing on the questions discussed in the etymological part, and in the Middle Ages. The hundredal system as a wbole is first to some general remarks on hundred-names and the like as shown in detail in Domesday - with the exception of some embodied in the material now collected. counties and smaller areas -- but is known to have existed about THE HUNDRED. a hundred and fifty years earlier. The hundred is mentioned in the laws of Edmund (940-6),' but no earlier evidence for its The hundred, it is generally admitted, is in theory at least a existence has been found. -

Anglo – Saxon Society

ABSTRACT This booklet will enable you to revise the key aspects of Paper 2 Anglo – Saxon England, some of which you may remember from year 9. After you have completed this booklet, there will be some more to revise Anglo – Saxon England before we move onto Norman England from 1066. Ms Marsh ANGLO – SAXON SOCIETY GCSE History Paper 2 How did Anglo – Saxon kings demonstrate their power? L.O: Explain key features of Anglo – Saxon kings 1. Which last Anglo – Saxon king ruled between 1042 - 1066? 2. Which people were the biggest threat to the Anglo – Saxons? 3. Who was at the top of Anglo – Saxon society? (Answers at the end of the booklet) Recap! The social hierarchy of Anglo – Saxon England meant that there were clear roles for everyone in society. The hierarchy was based on servitude – this meant that everyone had to do some sort of role to support the country. The king was the ultimate source of authority. This meant that all his decisions were final, partly due to the belief that God had chosen the king so any challenge to the king would be seen as a challenge to God. We call this belief anointed by God. Even though there were earldoms that were extremely powerful (see map below), most earls relied on the king to grant them their power and then maintain this power. Ultimately, the king could reduce the power of his earls or completely remove them. Edward the Confessor tried to do this in 1051, when he felt Earl Godwin had become too powerful – even though it ultimately failed, as Earl Godwin was allowed to regain his earldom, it demonstrates to us the huge power of the king. -

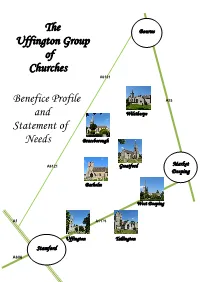

The Uffington Group of Churches Benefice Profile and Statement Of

The Bourne Uffington Group of Churches A6121 Benefice Profile A15 and Wilsthorpe Statement of Needs Braceborough A6121 Greatford Market Deeping Barholm West Deeping A1 A1175 Uffington Tallington Stamford A606 Introduction Thank you for taking an interest in the Uffington Group of Churches. If you are reading this to see whether you might be interested in becoming our next Rector, we hope you will find it helpful. If you are reading this for any other reason, we hope you will find this profile interesting, and if you are in the area, or might just be passing through, we hope that you might wish to come and see us. We hope that our new Rector will be able to inspire us in three key areas of our discipleship growth plans: drawing more of our villagers, especially from the missing generations, to respond to the message of the gospel (ie making more Christ-like Christians, as Bishop Edward King might have said); enhancing the faith of current members of our congregations (responding to the need for more Christ-like Christians, as Bishop Edward King did say); ensuring that our seven churches are not only kept open and functioning, but are made more attractive focal points for the lives of our parishioners and communities. We believe that such a person is likely to be: someone who will prayerfully seek to preach, teach and share scriptural truth; willing to grasp the nature of rural ministry; able to preserve the identity of each parish while maintaining coherence of the Group; comfortable with a range of worship and broad expression of faith; able to develop and communicate an inspirational vision for building God’s work amongst all ages in the Group and in each parish; able to lead, cultivate and enthuse teams of volunteers involved in the ministry, administration and upkeep of the seven churches; open, approachable and supportive, and willing to be visible at community events in all the villages; keen to guide and support the Christian ethos of the Uffington Church of England Primary School, being a regular visitor to the school and ex-officio governor. -

Researching Irish and Scots-Irish Ancestors an INTRODUCTION to the SOURCES and the ARCHIVES

Researching Irish and Scots-Irish Ancestors AN INTRODUCTION TO THE SOURCES AND THE ARCHIVES Ulster Historical Foundation Charity Registration No. NIC100280 Interest in researching Irish ancestors has never been greater. Given Ireland’s history of emigration, it is hardly surprising to find that around the world tens of millions of people have a family connection with the island. Much of this interest comes from Britain, the USA, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. What follows is a very basic introduction to researching Irish ancestors. It highlights what the major sources are and where they can be found. Prior to 1922 Ireland was under one jurisdiction and so where we refer to Ireland we mean the entire island. Where we are referring specifically to Northern Ireland or the Republic of Ireland we will try to make this clear. SOME BACKGROUND INFORMATION Exploding a myth an elderly person’s reminiscences prove to be an accurate A popular misconception about researching Irish ancestors is recollection of the facts. A family Bible is another possible that it is a fruitless exercise because so many records were source of information on your ancestors. Gathering this destroyed. There is no denying that the loss of so many information before you visit the archives can save a great deal records in the destruction of the Public Record Office, of time. Once you find out what you do know you will then Dublin, in 1922 was a catastrophe as far as historical and be aware of the gaps and will have a clearer idea of what you genealogical research is concerned.