Edinburgh Research Explorer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geography, Background Information, Civil Parishes and Islands

Geography – Background Information – Civil Parishes and Islands Civil Parishes Geography Branch first began plotting postcode boundaries in 1973. In addition to the creation of postcode boundaries, Geography Branch also assigned each postcode to an array of Scottish boundary datasets including civil parish boundaries. From 1845 to 1930, civil parishes formed part of Scotland’s local government system. The parishes, which had their origins in the ecclesiastical parishes of the Church of Scotland, often overlapped the then existing county boundaries, largely because they reflected earlier territorial divisions. Parishes have had no direct administrative function in Scotland since 1930. In 1930, all parishes were grouped into elected district councils. These districts were abolished in 1975, and the new local authorities established in that year often cut across civil parish boundaries. In 1996, there was a further re-organisation of Scottish local government, and a number of civil parishes now lie in two or more council areas. There are 871 civil parishes in Scotland. The civil parish boundary dataset is the responsibility of Geography Branch. The initial version of the boundaries was first created in the mid-1960s. The boundaries were plotted on to Ordnance Survey 1:10,000 maps using the written descriptions of the parishes. In the late 1980s Geography Branch introduced a Geographic Information System (called ‘GenaMap’) to its working practices. At this point the manually-plotted civil parish boundaries were digitised using the GenaMap system. In 2006, GenaMap was replaced by ESRI’s ArcGIS product, and the civil parish boundaries were migrated to the new system. At this stage, the Ordnance Survey digital product MasterMap was made available as the background map for Geography Branch’s digitising requirements. -

What Is Neighbourhood Planning?

Neighbourhood Planning Policy Statement This Statement provides an introduction to Neighbourhood Planning and the policy context. The Statement is also intended to set out clearly what the council’s role is in Neighbourhood Planning and how decisions will be made in relation to the Council’s responsibilities for Neighbourhood Planning. Introduction The role of Strategic Planning is to ensure that future needs are planned for sustainably. To ensure that enough homes are built, enough employment land is available, that community needs are met and that we protect and enhance our environment taking into account climate change. When developing the Local Plan we aim to engage communities as far as practicable. The Statement of Community Involvement (SCI) sets out our commitment and method to engaging with communities. We have a Local Plan mailing list that members of the public, businesses, organisations etc can join if they wish to receive consultation notifications from Strategic Planning. However the Government has acknowledged that communities often feel that it is hard to have a meaningful say. In response to this the Government introduced Neighbourhood Planning through the Localism Act 2011 to give control and power to communities. Neighbourhood Planning is optional. Communities either through a Parish Council or establishing themselves as a Neighbourhood Forum can choose to prepare a Neighbourhood Plan and / or Neighbourhood Development Orders. What is Neighbourhood Planning? Neighbourhood Plans Parish Councils or neighbourhood forums can develop a shared vision and planning policies through a Neighbourhood Plan. A Neighbourhood Plan is a plan prepared by a community guiding future development and growth. The plan may contain a vision, aims, planning policies, or allocation of key sites for specific kinds of development. -

Thanington Without Civil Parish and Council As Seen

THANINGTON WITHOUT CIVIL PARISH AND COUNCIL AS SEEN FROM THEIR MINUTE BOOKS 1894-1994 - AN INITIAL ASSESSMENT By Clive. H. Church ‘Rufflands’ 72A New House Lane, Canterbury CT 4 7BJ 01227-458437 07950-666488 [email protected] Originally posted on the website of Thanington Without Civil Parish Council on 4 April 2005 in PDF and HMTL versions. Subsequently updated and illustrated in 2014. For the original see http://www.thanington-pc.gov.uk/pchistory/history.html 1 THANINGTON WITHOUT CIVIL PARISH AND COUNCIL, AS SEEN FROM THEIR MINUTE BOOKS, 1894-1994 Tracing the development of a parish and its council is not easy. Neither constituents nor historians pay them much attention. Despite its importance in the past, local government is not now well regarded thanks to the centralization and mediaization of British political culture. Moreover, although there are many sources, including the recollections of parishioners, they are often not easily available. And memories are often fallible. However, we can get some way towards understanding them through their minute books. For, while these are far from complete records, they do allow us an insight into the organization and attitudes of a council as it emerged from the changing pattern of local government in England. For civil parishes have never been able to decide their own organization. This has been laid down by national legislation. In other words, they are creatures of Parliament. In the case of Thanington Without the minute books allow us to trace the evolution of both the original Parish Meeting and its successor and, after 1935, of the Parish Council itself. -

Foi Publishing Template

Freedom of Information Act Request Reference: F15/0323 Response Date: 21 December 2015 Thank you for your request for information. Your original request to Maldon District Council has been replicated below, together with the Council’s response: In accordance with the provisions of the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) 2000, I would like to make a formal request for the information set out below in relation to your local authority area (Maldon District Council). Civil parishes 1. Are there civil parishes in your local authority area? 2. If yes, is the entirety of your local authority area parished? 3. For each of parished parts of your local authority area, please provide the following information: a. The name of the civil parish. b. Whether it has a parish council or a parish meeting. c. Whether it is a precepting, group precepting, or non-precepting authority in the current financial year. d. If it has a parish council, what style (if any) does it have i.e. parish, town, community, village or city council? e. Elections: when, by year, (i) did they last take place, and (ii) are they next due to take place? (Please advise dates even if uncontested.) f. Are there individual (plural) wards within the parish, or is the whole parish one ward for the purposes of electing councillors? 4. If parts of your local authority area are unparished, please provide the following information in relation to each part: a. The name of the area which is unparished (i.e. name of town / village / community). b. Whether there is an established community forum (or similar) recognised by your local authority, for consultations etc. -

Parish' and 'City' -- a Shifting Identity: Salisbury 1440-1600

Early Theatre 6.1(2003) audrey douglas ‘Parish’ and ‘City’ – A Shifting Identity: Salisbury 1440–1600 The study and documentation of ceremony and ritual, a broad concern of Records of Early English Drama, has stimulated discussion about their purpose and function in an urban context. Briefly, in academic estimation their role is largely positive, both in shaping civic consciousness and in harmonizing diverse classes and interests while – as a convenient corollary – simultaneously con- firming local hierarchies. Profitable self-promotion is also part of this urban picture, since ceremony and entertainment, like seasonal fairs, potentially attracted interest from outside the immediate locality. There are, however, factors that compromise this overall picture of useful urban concord: the dominance of an urban elite, for instance, may effectually be stabilized, promoted, or even disguised by ceremony and ritual; on the other hand, margi- nalized groups (women and the poor) have normally no place in them at all.l Those excluded from participation in civic ritual and ceremonial might, nevertheless, be to some extent accommodated in the pre-Reformation infra- structure of trade guilds and religious guilds. Both organizational groups crossed social and economic boundaries to draw male and female members together in ritual and public expression of a common purpose and brotherhood – signalling again (in customary obit, procession, and feasting) harmony and exclusivity, themes with which, it seems, pre-Reformation urban life was preoccupied. But although women were welcome within guild ranks, office was normally denied them. Fifteenth-century religious guilds also saw a decline in membership drawn from the poorer members of society, with an overall tendency for a dominant guild to become identified with a governing urban elite.2 Less obvious perhaps, but of prime importance to those excluded from any of the above, was the parish church itself, whose round of worship afforded forms of ritual open to all. -

Stages for Preparing a Neighbourhood Plan

Stages for Preparing a Neighbourhood Plan Stage one The process is instigated by the Parish/Town Council or Neighbourhood Forum. Parish/Town Councils or Neighbourhood Forums should discuss their initial ideas with the Local Planning Authority to address any questions or concerns before coming forward for designation. The Planning Policy department will provide free advice to those seeking to establish a neighbourhood area. Stage two Designation of a Neighbourhood Area Parish or Town Councils or community groups wishing to be designated as a Neighbourhood Forum should submit a formal application to the Local Authority. This application should contain the following: For Parish/Town Councils: A map illustrating the proposed Neighbourhood Plan area (area boundary should be marked in red and any settlement boundary within the boundary identified should be marked in black). A statement explaining why this area is considered appropriate to be designated a Neighbourhood Area. A statement identifying that the Parish/Town Council are a ‘relevant body’ in accordance with 61G(2) of Schedule 9 of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990. For Neighbourhood Forums: The name of the proposed Neighbourhood Forum. A copy of the written constitution of the proposed neighbourhood forum A map illustrating the proposed neighbourhood plan area and the name of that area (area boundary should be marked in red and any settlement boundary within the boundary identified should be marked in black). The contact details of at least one member of the proposed forum to be made public. A statement explaining how the Neighbourhood Forum has satisfied the following requirements: That it is established for the express purpose of promoting or improving the social, economic and environmental well being of the area to be designated as Neighbourhood Area. -

Where Next for Neighbourhood Plans?

Where Next for Neighbourhood Plans? Can they withstand the external pressures? October 2018 Where next for neighbourhood plans? Can they withstand the external pressures? October 2018 Published by: National Association of Local Councils (NALC) 109 Great Russell Street, London, WC1B 3LD. 020 7637 1865 [email protected] www.nalc.gov.uk The authors of this report were: LILLIAN BURNS NALC National Assembly member and ANDY YUILLE Planning and environment consultant and PhD researcher Every effort has been made to ensure that the contents of this publication were correct at the time of printing. NALC does not undertake any liability for any error or omission. c NALC 2018 All rights reserved. All images except maps on pages 4 and 14 and infographics on pages 29 and 30 from Shutterstock. 2 Where next for neighbourhood plans? Can they withstand the external pressures? October 2018 PREFACE The National Association of Local Councils (NALC)1 has been hugely supportive of the concept of Neighbourhood Planning since its inception. We produced training materials including ‘How to shape where you live: a guide to neighbourhood planning’ jointly with the Campaign to Protect Rural England (CPRE) in 20122 and the ‘Good Councillors Guide to Neighbourhood Planning’ in 20173. Our County Associations have held neighbourhood planning seminars, often working with Community Councils and/or CPRE branches, and more than 2,000 Town and Parish Councils have engaged in the neighbourhood planning process4. Over 90% of NPs are led by Local Councils)4. The Commission on the Future of Localism estimated, in the ‘People Power’ report they published in 5 February that the communities involved in the process represented some 12 million people. -

A Review of Forum Governance Christopher Mountain Urban

Can you trust your Neighbourhood Forum? A review of Forum Governance Christopher Mountain Urban & Regional Planning MA University of Westminster Dissertation August 2019 1 Abstract Neighbourhood planning is the newest and most local tier of the English planning system. Since its introduction in 2011 it has unarguably changed the complexion of the planning system across much of the country. Despite widespread take-up, the process divides opinion. Neighbourhood Forums; the community groups that lead the neighbourhood planning process in areas with no civic town or parish council, have been one of the most contentious elements of a regime that, for the first time, enables local people to write their own statutory land use planning policies. Through neighbourhood planning, Forums have enormous potential to bring about significant spatial and social changes. Over 200 Forums are now established, predominantly in urban areas, with around 2,400 town or parish councils leading the process in more rural areas. If full coverage of Forums was achieved, around 66% of the population would be covered by their influence. In this context, this study draws on evidence from the first ever wide-spread survey of Forum governance, analysis of previously unreleased data on Forum skills and deprivation and feedback from Forums themselves. It aims to test the undercurrent of concerns that Forums can’t be trusted by getting under the skin of how these groups are run and makes recommendations based on current practice to improve Forum governance at a time when many will be considering whether to seek formal ‘re-designation’ for a further five-year term. -

Planning in Your Neighbourhood

Annex 1 The Royal Borough of Kingston upon Thames Draft Neighbourhood Planning Guidance A step-by-step guide for producing a Neighbourhood Plan and other options available through Neighbourhood Planning March 2016 1 Annex 1 2 Annex 1 Contents Foreword 1. You and the planning system 2. Forming a Neighbourhood Forum 3. Preparing your Neighbourhood Plan 4. Getting your Neighbourhood Plan adopted 5. Implementing your Neighbourhood Plan 6. Other alternatives 7. Support and advice Appendix 1: Glossary of planning terms 3 Annex 1 PAGE LEFT BLANK FOR PRINTING 4 Annex 1 [Foreword by Portfolio Holder for Regeneration] . 5 Annex 1 1. You and the planning system What is the planning system? The statutory town and country planning system in England is designed to regulate and control the development of land and buildings in the public interest. The modern planning system was introduced by the Town and Country Planning Act of 1947. There have been a series of further Acts over the succeeding years, with the main ones in use today being: the four 1990 Acts; the Planning and Compulsory Purchase Acts of 1991 and 2004; the Planning Act of 2008; and the planning provisions of the Localism Act 2011 – which allows the creation of Neighbourhood Plans. Supplementing the Acts are various Statutory Instruments, Ministerial Statements, and the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) and Planning Practice Guidance. The Planning Acts have included a presumption in favour of development since 1947. Development is defined in the 1990 Act as “the carrying out of building, engineering, mining or other operations in, on, over or under land” (known as operational development) or “the making of any material change of use of any buildings or other land”. -

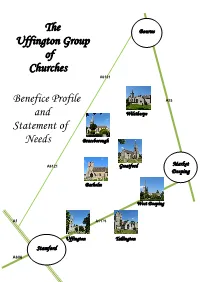

The Uffington Group of Churches Benefice Profile and Statement Of

The Bourne Uffington Group of Churches A6121 Benefice Profile A15 and Wilsthorpe Statement of Needs Braceborough A6121 Greatford Market Deeping Barholm West Deeping A1 A1175 Uffington Tallington Stamford A606 Introduction Thank you for taking an interest in the Uffington Group of Churches. If you are reading this to see whether you might be interested in becoming our next Rector, we hope you will find it helpful. If you are reading this for any other reason, we hope you will find this profile interesting, and if you are in the area, or might just be passing through, we hope that you might wish to come and see us. We hope that our new Rector will be able to inspire us in three key areas of our discipleship growth plans: drawing more of our villagers, especially from the missing generations, to respond to the message of the gospel (ie making more Christ-like Christians, as Bishop Edward King might have said); enhancing the faith of current members of our congregations (responding to the need for more Christ-like Christians, as Bishop Edward King did say); ensuring that our seven churches are not only kept open and functioning, but are made more attractive focal points for the lives of our parishioners and communities. We believe that such a person is likely to be: someone who will prayerfully seek to preach, teach and share scriptural truth; willing to grasp the nature of rural ministry; able to preserve the identity of each parish while maintaining coherence of the Group; comfortable with a range of worship and broad expression of faith; able to develop and communicate an inspirational vision for building God’s work amongst all ages in the Group and in each parish; able to lead, cultivate and enthuse teams of volunteers involved in the ministry, administration and upkeep of the seven churches; open, approachable and supportive, and willing to be visible at community events in all the villages; keen to guide and support the Christian ethos of the Uffington Church of England Primary School, being a regular visitor to the school and ex-officio governor. -

Researching Irish and Scots-Irish Ancestors an INTRODUCTION to the SOURCES and the ARCHIVES

Researching Irish and Scots-Irish Ancestors AN INTRODUCTION TO THE SOURCES AND THE ARCHIVES Ulster Historical Foundation Charity Registration No. NIC100280 Interest in researching Irish ancestors has never been greater. Given Ireland’s history of emigration, it is hardly surprising to find that around the world tens of millions of people have a family connection with the island. Much of this interest comes from Britain, the USA, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. What follows is a very basic introduction to researching Irish ancestors. It highlights what the major sources are and where they can be found. Prior to 1922 Ireland was under one jurisdiction and so where we refer to Ireland we mean the entire island. Where we are referring specifically to Northern Ireland or the Republic of Ireland we will try to make this clear. SOME BACKGROUND INFORMATION Exploding a myth an elderly person’s reminiscences prove to be an accurate A popular misconception about researching Irish ancestors is recollection of the facts. A family Bible is another possible that it is a fruitless exercise because so many records were source of information on your ancestors. Gathering this destroyed. There is no denying that the loss of so many information before you visit the archives can save a great deal records in the destruction of the Public Record Office, of time. Once you find out what you do know you will then Dublin, in 1922 was a catastrophe as far as historical and be aware of the gaps and will have a clearer idea of what you genealogical research is concerned. -

Parish Register Guide Entries for Painswick, Harescombe, Haresfield, Brookthorpe

East Dean ............................................................................................................................................................................................3 Eastington (Near Northleach) ...............................................................................................................................................................5 Eastington, Nr Stonehouse (St Michael) ..............................................................................................................................................7 Eastleach .............................................................................................................................................................................................9 Eastleach Martin (St Mary) ................................................................................................................................................................. 11 Eastleach Turville (St Andrew) ........................................................................................................................................................... 13 Ebrington (St Ethelburga) ................................................................................................................................................................... 15 Edge (St John the Baptist) ................................................................................................................................................................. 17 Edgeworth (St Mary)