The Role and Effectiveness of Parish Councils in Gloucestershire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Humberside Police Use Multi-WAN Solutions to Improve Connectivity Between Force and Central Command for Real-Time Decisions with HD Video

WIRED BROADCAST • CLIENT STORIES SERIES Humberside Police use multi-WAN solutions to improve connectivity between force and central command for real-time decisions with HD video Established in 1974 and located in Northeast England, Humberside Police serves the people of Northern Lincolnshire, Hull, and the East Riding of Yorkshire. Humberside Police has over 4,000 employees across 18 police stations and covers an area of more than 3,500 square kilometres spread over a diverse terrain. Challenge Humberside Police needed a technology solution to transmit HD video reliably from any location to the command center for real-time decisions in operations situation monitoring. Single-SIM routers had proven to be unreliable due to limitations in cellular coverage, bandwidth, and signal strength. Also, line of sight was not always available to enable satellite connections. These limitations were showstoppers for Humberside. While the police team may not know in advance where they’ll be deployed, they do need to be sure they’ll have reliable high-bandwidth connectivity wherever they are called. +44 (0) 20 3376 7710 +1 (813) 895 3799 (US) © 2020 WIRED BROADCAST LTD [email protected] BEROL HOUSE, 25 ASHLEY ROAD, LONDON N17 9LJ Solution In 2015, Gary Woolston, Technical Support Manager at Humberside, Results learned of Wired Broadcast’s multi- WAN ofering at the Security & Policing tradeshow. Soon after, Humberside purchased three multi-WAN devices, using SIMs from Vodafone, EE, 02, Cellular carrier coverage, bandwidth, and Three. “We had tested numerous » Improved cellular carrier and signal strength are no longer service providers, but they all had coverage, bandwidth, an issue for Humberside Police. -

Defibrillators in the Cirencester Area (GL7)

Defibrillators in the Cirencester Area (GL7) Location Location detail Location Area Post Code Ampney Crucis Primary School School Lane School Lane Ampney Crucis GL7 5SD Ampney Crucis Village Hall Main Street Ampney Crucis GL7 5RY Friends of Ampney St Mary Ampney St Mary Red Telephone Box Ampney St Mary GL7 5SP Bibury Trout Farm Rack Isle Building Bibury GL7 5NL 31 Morestall Drive Fixed to outside of building Chesterton Cirencester GL7 1TF Ashcroft Church Fixed to outside of building Ashcroft Road Cirencester GL7 1RA Baunton Telephone Box Baunton 7 Mill View Cirencester GL7 7BB Bibury Football Club Bibury Aldsworth Road Cirencester GL7 5PB Chesterton Primary School Apsley Road Entrance Hall Cirencester GL71SS Cirencester Baptist Church Fixed to outside of building Chesterton Lane Cirencester GL7 1YE Cirencester College (David Building) Stroud Road Cirencester GL7 1XA Cirencester Deer Park School Stroud Road Sports Department Cirencester GL7 1XB Cirencester Deer Park School Stroud Road Caretaker's Office Cirencester GL7 1XB Coln St Aldwyn Telephone Box Coln St Aldwyns Outside Old Post Office Cirencester GL7 5AA Dot Zinc Cecily Hill The Castle Cirencester GL7 2EF Housing 21 - Mulberry Court Middle Mead Cirencester GL7 1GG Kemble and Ewen The Tavern Kemble Station Road Cirencester GL7 6AX Market Place On railing by Noticeboard Market Place Cirencester GL7 2NW Masonic Hall The Avenue Cirencester GL7 1EH Last Updated: 18/07/19 Defibrillators in the Cirencester Area (GL7) Location Location detail Location Area Post Code Morestall Drive 31 Morestall -

Fieldways, 3 Whitewater Road, Leighterton, Tetbury

Fieldways, 3 Whitewater Road, Leighterton, Tetbury, Gloucestershire, GL8 8UJ Semi-Detached Period Home Mature Wrap Around Garden Edge of village position 3 Receptions 4 Bedrooms 3 Bathrooms Integral Self-Contained Flat 4 The Old School, High Street, Sherston, SN16 0LH Garage & Parking James Pyle Ltd trading as James Pyle & Co. Registered in England & Wales No: 08184953 Rural Outlook Approximately 0.18 acres Price Guide: £750,000 Approximately 1,884 sq ft ‘Positioned on the rural edge of Leighterton with countryside views, this delightful semi- detached period home is set amongst mature wrap around gardens’ The Property There are four bedrooms over the first floor Wotton-under-Edge. The village has a Tenure & Services all with a countryside outlook. The pretty church, duck pond and popular Fieldways is a delightful semi-detached northern wing of the first floor is currently primary school as well as the well-regarded We understand the property is Freehold period home set amongst open farmland on arranged as a self-contained flat complete Royal Oak pub. Both the market town of with oil fired central heating, mains the rural edge of the popular village of with a kitchenette, living room, shower Tetbury and Wotton-under-Edge have a drainage and water. Leighterton. Believed to date back to 1890 room and bedroom. The flat has been used broad range of shops and amenities for as formerly five workers cottages then later for BnB and is equally useful for a everyday needs as well as a number of Directions extended and split into two dwellings, the dependant relative. -

The Byre Manor Farm Yard, Ampney St Mary, Cirencester, Gloucestershire GL7 5SP the Byre £725,000 Manor Farm Yard Ampney St Mary Cirencester Gloucestershire GL7 5SP

The Byre Manor Farm Yard, Ampney St Mary, Cirencester, Gloucestershire GL7 5SP The Byre £725,000 Manor Farm Yard Ampney St Mary Cirencester Gloucestershire GL7 5SP Manor Farm Barns is an exceptional development of just three conversions of former agricultural barns. Centrally located within the heart of this desirable village, the properties are Listed Grade II for their historical importance. The developers have skilfully, yet sympathetically converted the three individual barns providing bright and spacious accommodation for modern day living. The re-development of these traditional barns blends perfectly within the village’s conservation area. Utilising traditional materials each barn has been converted with its own individual specification and set in their own landscaped gardens. THE BYRE A unique period home that has been beautifully converted offering flexible accommodation. The entrance hall leads into the fabulous kitchen, cloakroom and steps lead up to the open plan living area with stairwell to first floor and two large windows onto the parking area. The kitchen oozes light from a selection of windows and glazed doors that overlook the heavily planted garden, with space for dining, the kitchen provides a good selection of fitted units and island. Off the kitchen lies the home office or occasional bedroom four. There is a principal bedroom with en suite shower room on the ground floor. To the first floor, two further double bedrooms are located one with en suite wet room and a further bathroom. The property has a paved terrace, planted garden enclosed by estate fencing and ample parking. AMPNEY ST MARY The neighbouring villages of Ampney Crucis 1.4 miles and Poulton COMMUNICATION Set away from main roads, the charming hamlet of Ampney St Mary 1.4 miles each offer a public house, there is a community shop in BY TRAIN lies approximately 4 miles to the east of Cirencester. -

4542 the London Gazette, 21 August, 1953

4542 THE LONDON GAZETTE, 21 AUGUST, 1953 Railway Line by way of an overhead reinforced Standish—Hope Cottage, Gloucester Road, Stone- concrete footbridge with approaches. house. A certified copy of the Order and of the map con- Tirley—Torsend Cottage, Tirley. tained in the Order as confirmed by the Minister has Twigworth—c/o Mr. E. J. Jones, Far End, Twig- been deposited at the Council Offices, Argyle Road* worth. Sevenoaks, and will be open for inspection free of Upton St. Leonards—'Village Hall, Upton St. charge between the hours of 9 a.m. and 5.30 p.m. on Leonards. Weekdays and between 9 a.m. and 12 noon on Westbury-on-Severn—Lecture Hall, Westbury-on- Saturday. Severn. The Order becomes operative as from 'the 21st Whitminster—c/o iMr. A. E. Wyer, The Garage, day of August, 1953, but if any person aggrieved Whitminster. by the Order desires to question the validity thereof In exceptional circumstances special arrangements or of any provision contained therein on the grounds will be made for the draft map and statement to be that it is not within the powers of the National Parks inspected out of office hours. and Access to the Countryside Act, 1949, or on the Any objection or representation with respect to ground -that any requirement of the Act or any the draft map or statement may be sent in writ- regulation made thereunder has not been complied ing to the undersigned before the 30th day of April, with in relation to the approval of the Order he 1954, and any such objection or representation should may. -

In 1968. the Report Consists of the Following Parts: L the Northgate Turnpike Roads 2 Early Administration and the Turnpike Trust

Reprinted from: Gloucestershire Society for Industrial Archaeology Journal for 1971 pages 1-58 [This edition was reprinted in 1987 by the Author in Hong Kong with corrections and revised pagination] THE NQRIH§AIE.IHBNBlKE N SPRY For more than one hundred and seventy years the road from the city of Gloucester to the top of Birdlip Hill, and the road which branched eastwards from it up Crickley Hill towards Oxford and later London, was maintained from the proceeds of the various turnpikes or toll gates along it. This report examines the history and administration of these roads from their earliest period to the demise of the Turnpike Trust in l87l and also details excavations across the road at Wotton undertaken in 1968. The report consists of the following Parts: l The Northgate Turnpike roads 2 Early administration and the Turnpike Trust 3 Tolls, exemptions and traffic 4 Road materials 5 Excavations at Wotton 1968 I Summary II The Excavations III Discussion References 1 IHE.NQBIH§AIE.BQADfi The road to Gloucester from Cirencester and the east is a section of the Roman road known as Ermine Street. The line of this road from Brockworth to Wotton has been considered to indicate a Severn crossing at Kingsholm one Km north of Gloucester, where, as late as the seventeenth century, a major branch of the river flowed slightly west of modern Kingsholm. The extent of early Roman archaeological material from Kingsholm makes it likely to have been a military site early in the Roman period. (l) Between Wotton Hill and Kingsholm this presumed line is lost; the road possibly passed through the grounds of Hillfield House and along the ridge, now marked by Denmark Road, towards the river. -

Implementing Community Led Care in the Non-Linked Isles of Orkney

Implementing Community Led Care In the Non-Linked Isles of Orkney 1 This project is a result of a partnership between Voluntary Action Orkney, Highlands and Islands Enterprise, Robert Gordon University, and the island development trusts of Eday, Hoy, Sanday, Shapinsay, Stronsay, Rousay Egilsay and Wyre and the Community Council of Papa Westray. This project was funded through the Aspiring Communities Fund, a Scottish Government fund delivered with European Social Funds. Report prepared by Rosie Alexander, Research Officer With the support of Dr Sue Barnard, Academic Supervisor Report Published: 14th May 2018 Enquiries about this report should be directed to: [email protected] The researchers would like to express their grateful thanks to all who supported with this project, taking the time to meet with the research team, discuss existing health and care services, and share ideas for future developments. 2 Contents 1. Executive Summary ............................................................................................................ 4 2. Context and methodology .................................................................................................. 9 3. The landscape of Health and Care ................................................................................... 10 3.1 Key Policy Drivers in Health and Care ......................................................................... 10 3.2 Home Care ................................................................................................................. -

Lower Field Barn READY TOKEN • NR AMPNEY ST MARY • CIRENCESTER • GLOUCESTERSHIRE Lower Field Barn READY TOKEN • NR AMPNEY ST MARY CIRENCESTER • GLOUCESTERSHIRE

Lower Field Barn READY TOKEN • NR AMPNEY ST MARY • CIRENCESTER • GLOUCESTERSHIRE Lower Field Barn READY TOKEN • NR AMPNEY ST MARY CIRENCESTER • GLOUCESTERSHIRE A fabulous Cotswold stone barn conversion situated in a peaceful rural location with views over the Coln Valley. Entrance hall • Sitting room • Kitchen/breakfast room Cloakroom • Utility room • Drawing room Master bedroom with en-suite bathroom and dressing room 4 further bedrooms • Shower room Parking • Double garage with store room Gardens • Paddocks • 2 stables In all about 3 acres (1.23 ha) Cirencester 4 miles • Fairford 5 miles Kemble Station (Paddington 80 minutes) 9 miles Swindon (Paddington 55 minutes) 17 miles • M4 (J15) 20 miles M5 (J11A) 19 miles • Cheltenham 20 miles (All distances and times are approximate) These particulars are intended only as a guide and must not be relied upon as statements of fact. Your attention is drawn to the Important Notice on the last page of the text. Gloucestershire • Lower Field Barn is situated in a wonderful rural position at the • Kemble Railway Station, about 11 miles away, provides • The property is not listed and was converted 12 years ago to end of a long drive about ½ a mile from the hamlet of Ready an efficient train service to London Paddington. Swindon provide a particularly light and airy country home. Token which is close to the sought after villages of Barnsley and also provides an excellent service with high speed trains to • The accommodation is arranged over three floors and is ideal Bibury. Both villages have a number of local amenities including Paddington taking about 55 minutes. -

Annual Report 2016–2017

Annual Report 2016–2017 Annual Report 2016–2017 Published pursuant to section 18 of the Judiciary and Courts (Scotland) Act 2008 Laid before the Scottish Parliament by the Scottish Ministers SG/2017/132 © Judicial Appointments Board for Scotland (JABS) copyright 2017 The text in this document (this excludes, where present, the Royal Arms and all departmental or agency logos) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium provided that it is reproduced accurately and not in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as JABS copyright and the document title specified. Where third party material has been identified, permission from the respective copyright holder must be sought. Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at: Judicial Appointments Board for Scotland Thistle House 91 Haymarket Terrace Edinburgh EH12 5HD E-mail: [email protected] This publication is only available on our website at www.judicialappointments.scot Published by the Judicial Appointments Board for Scotland, September 2017 Designed in the UK by LBD Creative Ltd Annual Report 2016–2017 Contents Our aims ii Foreword 1 Introduction and Membership 3 Committees and Groups 6 Diversity 11 Appointment Rounds 12 Meetings and Outreach 20 Tribunals 21 Complaints 22 Freedom of Information 23 Secretariat 24 Website 25 Financial Statement 26 Annex 1: Board Members and Lay Selection Panel Members 27 Annex 2: Board Member Attendance 33 i i JUDICIAL APPOINTMENTS BOARD FOR SCOTLAND Our aims are: To attract applicants of the highest calibre, to encourage diversity in the range of those available for selection, and to recommend applicants for appointment to judicial office on merit through processes that are fair, transparent and command respect. -

BGS Report, Single Column Layout

Mineral Resource Information in Support of National, Regional and Local Planning Humberside (comprising East Riding of Yorkshire, North Lincolnshire, North East Lincolnshire and City of Kingston upon Hull). Commissioned Report CR/04/227N BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY COMMISSIONED REPORT CR/04/227N Mineral Resource Information in Support of National, Regional and Local Planning Humberside (comprising East Riding of Yorkshire, North Lincolnshire, North east Lincolnshire and City of Kingston upon Hull) D J Harrison, F M McEvoy, P J Henney, D G Cameron, E J Steadman, S F Hobbs, N A Spencer, D J Evans, G K Lott, E M Bartlett, M H Shaw, D E Highley and T B Colman The National Grid and other Ordnance Survey data are used This report accompanies the 1:100 000 scale map: Humberside with the permission of the Mineral Resources Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. Licence No: 100017897/2005. Keywords Mineral resources, mineral planning, East Yorkshire and Humberside. Front cover Excavator working bed of sand from recent Blown Sand (Recent) at Cove Farm Quarry near Haxey. Bibliographical reference HARRISON, D J, and 12 others, 2005. Mineral Resource Information in Support of National, Regional and Local Planning - East Yorkshire and Humberside. British Geological Survey Commissioned Report, CR/04/227N. 18pp © Crown Copyright 2005. Keyworth, Nottingham British Geological Survey 2005 BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY The full range of Survey publications is available from the BGS British Geological Survey offices Sales Desks at Nottingham, Edinburgh and London; see contact details below or shop online at www.geologyshop.com Keyworth, Nottingham NG12 5GG The London Information Office also maintains a reference 0115-936 3241 Fax 0115-936 3488 collection of BGS publications including maps for consultation. -

GLOUCESTERSHIRE Extracted from the Database of the Milestone Society

Entries in red - require a photograph GLOUCESTERSHIRE Extracted from the database of the Milestone Society National ID Grid Reference Road No. Parish Location Position GL_AVBF05 SP 102 149 UC road (was A40) HAMPNETT West Northleach / Fosse intersection on the verge against wall GL_AVBF08 SP 1457 1409 A40 FARMINGTON New Barn Farm by the road GL_AVBF11 SP 2055 1207 A40 BARRINGTON Barrington turn by the road GL_AVGL01 SP 02971 19802 A436 ANDOVERSFORD E of Andoversford by Whittington turn (assume GL_SWCM07) GL_AVGL02 SP 007 187 A436 DOWDESWELL Kilkenny by the road GL_BAFY07 ST 6731 7100 A4175 OLDLAND West Street, Oldland Common on the verge almost opposite St Annes Drive GL_BAFY07SL ST 6732 7128 A4175 OLDLAND Oldland Common jct High St/West Street on top of wall, left hand side GL_BAFY07SR ST 6733 7127 A4175 OLDLAND Oldland Common jct High St/West Street on top of wall, right hand side GL_BAFY08 ST 6790 7237 A4175 OLDLAND Bath Road, N Common; 50m S Southway Drive on wide verge GL_BAFY09 ST 6815 7384 UC road SISTON Siston Lane, Webbs Heath just South Mangotsfield turn on verge GL_BAFY10 ST 6690 7460 UC road SISTON Carsons Road; 90m N jcn Siston Hill on the verge GL_BAFY11 ST 6643 7593 UC road KINGSWOOD Rodway Hill jct Morley Avenue against wall GL_BAGL15 ST 79334 86674 A46 HAWKESBURY N of A433 jct by the road GL_BAGL18 ST 81277 90989 A46 BOXWELL WITH LEIGHTERTON near Leighterton on grass bank above road GL_BAGL18a ST 80406 89691 A46 DIDMARTON Saddlewood Manor turn by the road GL_BAGL19 ST 823 922 A46 BOXWELL WITH LEIGHTERTON N of Boxwell turn by the road GL_BAGL20 ST 8285 9371 A46 BOXWELL WITH LEIGHTERTON by Lasborough turn on grass verge GL_BAGL23 ST 845 974 A46 HORSLEY Tiltups End by the road GL_BAGL25 ST 8481 9996 A46 NAILSWORTH Whitecroft by former garage (maybe uprooted) GL_BAGL26a SO 848 026 UC road RODBOROUGH Rodborough Manor by the road Registered Charity No 1105688 1 Entries in red - require a photograph GLOUCESTERSHIRE Extracted from the database of the Milestone Society National ID Grid Reference Road No. -

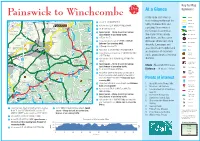

Painswick to Winchcombe Cycle Route

Great Comberton A4184 Elmley Castle B4035 Netherton B4632 B4081 Hinton on the Green Kersoe A38 CHIPPING CAMPDEN A46(T) Aston Somerville Uckinghall Broadway Ashton under Hill Kemerton A438 (T) M50 B4081 Wormington B4479 Laverton B4080 Beckford Blockley Ashchurch B4078 for Tewkesbury Bushley B4079 Great Washbourne Stanton A38 A38 Key to Map A417 TEWKESBURY A438 Alderton Snowshill Day A438 Bourton-on-the-Hill Symbols: B4079 A44 At a Glance M5 Teddington B4632 4 Stanway M50 B4208 Dymock Painswick to WinchcombeA424 Linkend Oxenton Didbrook A435 PH A hilly route from start to A Road Dixton Gretton Cutsdean Hailes B Road Kempley Deerhurst PH finish taking you through the Corse Ford 6 At fork TL SP BRIMPSFIELD. B4213 B4211 B4213 PH Gotherington Minor Road Tredington WINCHCOMBE Farmcote rolling Cotswold hills and Tirley PH 7 At T junctionB4077 TL SP BIRDLIP/CHELTENHAM. Botloe’s Green Apperley 6 7 8 9 10 Condicote Motorway Bishop’s Cleeve PH Several capturing the essence of Temple8 GuitingTR SP CIRENCESTER. Hardwicke 22 Lower Apperley Built-up Area Upleadon Haseld Coombe Hill the Cotswold countryside. Kineton9 Speed aware – Steep descent on narrow B4221 River Severn Orchard Nook PH Roundabouts A417 Gorsley A417 21 lane. Beware of oncoming traffic. The route follows mainly Newent A436 Kilcot A4091 Southam Barton Hartpury Ashleworth Boddington 10 At T junction TL. Lower Swell quiet lanes, and has some Railway Stations B4224 PH Guiting Power PH Charlton Abbots PH11 Cross over A 435 road SP UPPER COBERLEY. strenuous climbs and steep B4216 Prestbury Railway Lines Highleadon Extreme Care crossing A435. Aston Crews Staverton Hawling PH Upper Slaughter descents.