Scotland Research Outline

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

34 Dirleton Avenue, North Berwick, East Lothian, Eh39 4Bh Former Macdonald Marine Hotel Staff Accommodation Building

34 DIRLETON AVENUE, NORTH BERWICK, EAST LOTHIAN, EH39 4BH FORMER MACDONALD MARINE HOTEL STAFF ACCOMMODATION BUILDING FOR SALE PRIME DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY Prime development opportunity in highly desirable coastal town of North Berwick Non-listed building occupying a generous plot of 0.5 acres (0.20 ha) Potential for redevelopment to high quality apartments, single house or flatted development (subject to planning) 25-miles from Edinburgh City Centre Moments from world-renowned golf courses and High Street amenities Total Gross Internal Area approximately 846.28 sq m (9,108 sq ft) Inviting offers over £1,353,000 ex VAT FOR SALE | PRIME DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY ALLIED SURVEYORS SCOTLAND | 2 LOCATION AND SITUATION North Berwick is one of Scotland’s most affluent coastal towns with a population of approximately 14,000 people. With its world-renowned links golf courses, vibrant town centre and white sandy beaches, the East Lothian town is highly sought after by visitors, residents and investors. Situated approximately 25 miles east of Scotland’s capital city, Edinburgh, it benefits from close proximity to the A1 trunk road. The town’s train station, meanwhile, provides regular direct services to Edinburgh Waverley, talking around 30 minutes to reach the city centre. The subjects are situated in a residential district on Dirleton Avenue, the principal route leading into and out of North Berwick, at the crossroads with Hamilton Road. The property is less than 1-mile away from the town’s High Street where a wide range of amenities are on offer including many independent shops, restaurants, galleries, coffee houses and boutiques. FOR SALE | PRIME DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY ALLIED SURVEYORS SCOTLAND | 3 DESCRIPTION The subjects comprise a second smaller access further a substantial four-storey down Hamilton Road leading to a single garage and driveway. -

2 Legal System of Scotland

Legal System of 2 Scotland Yvonne McLaren and Josephine Bisacre This chapter discusses the formal sources of Scots law – answering the question of where the law gets its binding authority from. The chapter considers the role played by human rights in the Scottish legal system and their importance both for individuals and for businesses. While most com- mercial contracts are fulfilled and do not end up in court, some do, and sometimes businesses are sued for negligence, and they may also fall foul of the criminal law. Therefore the latter part of the chapter discusses the civil and criminal courts of Scotland and the personnel that work in the justice system. The Scottish legal system is also set in its UK and European context, and the chapter links closely with Chapters 3 and 4, where two rather dif- ferent legal systems – those in Dubai and Malaysia – are explored, in order to provide some international comparisons. The formal sources of Scots Law: from where does the law derive its authority? What is the law and why should we obey it? These are important ques- tions. Rules come in many different guises. There are legal rules and other rules that may appear similar in that they invoke a sense of obligation, such as religious rules, ethical or moral rules, and social rules. People live by religious or moral codes and consider themselves bound by them. People honour social engagements because personal relationships depend on this. However, legal rules are different in that the authority of the state is behind them and if they are not honoured, ultimately the state will step in 20 Commercial Law in a Global Context and enforce them, in the form of civil remedies such as damages, or state- sanctioned punishment for breach of the criminal law. -

A Soldier Fights for Three Separate but Sometimes Associated Reasons: for Duty, for Payment and for Cause

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Stirling Online Research Repository The press and military conflict in early modern Scotland by Alastair J. Mann A soldier fights for three separate but sometimes associated reasons: for duty, for payment and for cause. Nathianiel Hawthorne once said of valour, however, that ‘he is only brave who has affections to fight for’. Those soldiers who are prepared most readily to risk their lives are those driven by political and religious passions. From the advent of printing to the present day the printed word has provided governments and generals with a means to galvanise support and to delineate both the emotional and rational reasons for participation in conflict. Like steel and gunpowder, the press was generally available to all military propagandists in early modern Europe, and so a press war was characteristic of outbreaks of civil war and inter-national war, and thus it was for those conflicts involving the Scottish soldier. Did Scotland’s early modern soldiers carry print into battle? Paul Huhnerfeld, the biographer of the German philosopher and Nazi Martin Heidegger, provides the curious revelation that German soldiers who died at the Russian front in the Second World War were to be found with copies of Heidegger’s popular philosophical works, with all their nihilism and anti-Semitism, in their knapsacks.1 The evidence for such proximity between print and combat is inconclusive for early modern Scotland, at least in any large scale. Officers and military chaplains certainly obtained religious pamphlets during the covenanting period from 1638 to 1651. -

List of the Old Parish Registers of Scotland 758-811

List of the Old Parish Registers Midlothian (Edinburgh) OPR MIDLOTHIAN (EDINBURGH) 674. BORTHWICK 674/1 B 1706-58 M 1700-49 D - 674/2 B 1759-1819 M 1758-1819 D 1784-1820 674/3 B 1819-54 M 1820-54 D 1820-54 675. CARRINGTON (or Primrose) 675/1 B 1653-1819 M - D - 675/2 B - M 1653-1819 D 1698-1815 675/3 B 1820-54 M 1820-54 D 1793-1854 676. COCKPEN* 676/1 B 1690-1783 M - D - 676/2 B 1783-1819 M 1747-1819 D 1747-1813 676/3 B 1820-54 M 1820-54 D 1832-54 RNE * See Appendix 1 under reference CH2/452 677. COLINTON (or Hailes) 677/1 B 1645-1738 M - D - 677/2 B 1738-1819* M - D - 677/3 B - M 1654-1819 D 1716-1819 677/4 B 1815-25* M 1815-25 D 1815-25 677/5 B 1820-54*‡ M 1820-54 D - 677/6 B - M - D 1819-54† RNE 677/7 * Separate index to B 1738-1851 677/8 † Separate index to D 1826-54 ‡ Contains index to B 1852-54 Surname followed by forename of child 678. CORSTORPHINE 678/1 B 1634-1718 M 1665-1718 D - 678/2 B 1709-1819 M - D - 678/3 B - M 1709-1819 D 1710-1819 678/4 B 1820-54 M 1820-54 D 1820-54 List of the Old Parish Registers Midlothian (Edinburgh) OPR 679. CRAMOND 679/1 B 1651-1719 M - D - 679/2 B 1719-71 M - D - 679/3 B 1771-1819 M - D - 679/4 B - M 1651-1819 D 1816-19 679/5 B 1819-54 M 1819-54 D 1819-54* * See library reference MT011.001 for index to D 1819-54 680. -

Carment's Directory for Dalkeith And

ti i^^mtmi^ki ^1 o m h . PUBLICATION. § FIFTEENTH YEAR OF §\ \ .1 ^^^ l.^j GARMENT'S DIRECTORY hx §alkit| anb district, AND YEAR BOOK FOR •^ 1S9Q. *^ S'R.ICE-THIK.ElEI'lLllTCE. ,^9^^^^^^^:, DALKEITH. Founded 1805, The Oldest Scottish Insurance Office. GALEDONIAK INSURANCE COMPANY. INCOME, £628,674. FUNDS, £2,042,554, CLAIMS PAID EXCEED £5,500,000. LIFE ASSUEANCES AEE GRANTED WITH AND WITHOUT MEDICAL EXAMINATION ON VERY LIBERAL TERMS. Bonuses may le applied to make a whole-cf-life policy pay able diiriiig lifetime. Intermediate Bonuses are allowed. Perfect Non-forfeitable System. Policies in most cases unrestricted as regards Occupation and Foreign Residence or Travel. Claims payable 10 days after proof of death and title. FIRE DEPARTMENT. Security of the Highest Order. Moderate Premiums. Losses Promptly Settled. Surveys made J^ree of Charge. Head Office : 19 aEORGB STREET, EDINBURGH. Agents- IN Dalkeith— GEORGE JACK, S.S.C, Fairfield Place. JOHN GARMENT, 67 High Street. COLIN COCHRANE, Painter, 16 South Street. GEORGE PORTEOUS, 70 High Street ADVERTISEMENTS The Largest and Finest Selection of Music and Musical Instruments in the Kingdom. IMPORTANT. CHEAP AND GOOD PIANOS. THOROUGHLY GUARANTEED. An impression having got abroad that Paterson & Sons only deal in the Higher Class Pianos, they respectfully inform the Public that they keep always in Stock the Largest Selection in Town of the Cheaper Class of Good Sound Cottage Pianos, both New and Second H.and^ and their extensive deahngs with t^^e! • Che^^er Makers of the Best Class, eiiS^lgj;hg,isi|v^b, meet the Require- ments of all Mt^nding Bu^Vrs. -

Parish of Saline

PARISH OF SALINE. THIS PARISH, containing the village of its own name, is on the west border of the County. It is bounded by Clackmannanshire and the Culross district of Perthshire on the west, by a detached portion of Torryburn and part of Kinross-shire on the north, by Dunfermline and Carnock on the east, and by Carnock, part of Clackmannanshire, and the Culross district of Perthshire, on the south. Its length west-ward is about five and a half miles, and its extreme breadth, including a detached section, is five miles. The detached section to the south has been exchanged, Quoad Sacra, for another detached portion of Torryburn, situated to the north of Saline; but, Quoad Civilia, the detached portions are still connected with the original parishes. The eastern district, comprising about one half of the entire area, is of an upland character, rising into a lofty ridge called the Saline Hills, several peaks of which are upwards of 1000 feet high; the highest being Saline Hill, which is 1178 feet above the level of the sea. This district, though chiefly pastoral, and partly marshy, includes some good arable tracts. The soil of the western half, which is comparatively level, is generally a mixture of clay and loam, incumbent on till, yet in some places very fertile. Coal, limestone, and iron-stone, abound; and mining operations are actively carried on. The antiquities are two Roman Camps and two old Towers. Roads traverse the Parish both from north to south and from east to west; and the Oakley station of the Stirling and Dunfermline Railway is on the south border. -

THE MYTHOLOGY, TRADITIONS and HISTORY of Macdhubhsith

THE MYTHOLOGY, TRADITIONS and HISTORY OF MacDHUBHSITH ― MacDUFFIE CLAN (McAfie, McDuffie, MacFie, MacPhee, Duffy, etc.) VOLUME 2 THE LANDS OF OUR FATHERS PART 2 Earle Douglas MacPhee (1894 - 1982) M.M., M.A., M.Educ., LL.D., D.U.C., D.C.L. Emeritus Dean University of British Columbia This 2009 electronic edition Volume 2 is a scan of the 1975 Volume VII. Dr. MacPhee created Volume VII when he added supplemental data and errata to the original 1792 Volume II. This electronic edition has been amended for the errata noted by Dr. MacPhee. - i - THE LIVES OF OUR FATHERS PREFACE TO VOLUME II In Volume I the author has established the surnames of most of our Clan and has proposed the sources of the peculiar name by which our Gaelic compatriots defined us. In this examination we have examined alternate progenitors of the family. Any reader of Scottish history realizes that Highlanders like to move and like to set up small groups of people in which they can become heads of families or chieftains. This was true in Colonsay and there were almost a dozen areas in Scotland where the clansman and his children regard one of these as 'home'. The writer has tried to define the nature of these homes, and to study their growth. It will take some years to organize comparative material and we have indicated in Chapter III the areas which should require research. In Chapter IV the writer has prepared a list of possible chiefs of the clan over a thousand years. The books on our Clan give very little information on these chiefs but the writer has recorded some probable comments on his chiefship. -

Etymology of the Principal Gaelic National Names

^^t^Jf/-^ '^^ OUTLINES GAELIC ETYMOLOGY BY THE LATE ALEXANDER MACBAIN, M.A., LL.D. ENEAS MACKAY, Stirwng f ETYMOLOGY OF THK PRINCIPAL GAELIC NATIONAL NAMES PERSONAL NAMES AND SURNAMES |'( I WHICH IS ADDED A DISQUISITION ON PTOLEMY'S GEOGRAPHY OF SCOTLAND B V THE LATE ALEXANDER MACBAIN, M.A., LL.D. ENEAS MACKAY, STIRLING 1911 PRINTKD AT THE " NORTHERN OHRONIOLB " OFFICE, INYBRNESS PREFACE The following Etymology of the Principal Gaelic ISTational Names, Personal Names, and Surnames was originally, and still is, part of the Gaelic EtymologicaJ Dictionary by the late Dr MacBain. The Disquisition on Ptolemy's Geography of Scotland first appeared in the Transactions of the Gaelic Society of Inverness, and, later, as a pamphlet. The Publisher feels sure that the issue of these Treatises in their present foim will confer a boon on those who cannot have access to them as originally published. They contain a great deal of information on subjects which have for long years interested Gaelic students and the Gaelic public, although they have not always properly understood them. Indeed, hereto- fore they have been much obscured by fanciful fallacies, which Dr MacBain's study and exposition will go a long way to dispel. ETYMOLOGY OF THE PRINCIPAI, GAELIC NATIONAL NAMES PERSONAL NAMES AND SURNAMES ; NATIONAL NAMES Albion, Great Britain in the Greek writers, Gr. "AXfSiov, AX^iotv, Ptolemy's AXovlwv, Lat. Albion (Pliny), G. Alba, g. Albainn, * Scotland, Ir., E. Ir. Alba, Alban, W. Alban : Albion- (Stokes), " " white-land ; Lat. albus, white ; Gr. dA</)os, white leprosy, white (Hes.) ; 0. H. G. albiz, swan. -

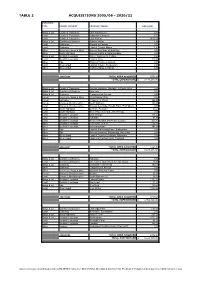

Table 2-Acquisitions (Web Version).Xlsx TABLE 2 ACQUISITIONS 2005/06 - 2020/21

TABLE 2 ACQUISITIONS 2005/06 - 2020/21 PURCHASE TYPE FOREST DISTRICT PROPERTY NAME AREA (HA) Bldgs & Ld Cowal & Trossachs Edra Farmhouse 2.30 Land Cowal & Trossachs Ardgartan Campsite 6.75 Land Cowal & Trossachs Loch Katrine 9613.00 Bldgs & Ld Dumfries & Borders Jufrake House 4.86 Land Galloway Ground at Corwar 0.70 Land Galloway Land at Corwar Mains 2.49 Other Inverness, Ross & Skye Access Servitude at Boblainy 0.00 Other North Highland Access Rights at Strathrusdale 0.00 Bldgs & Ld Scottish Lowlands 3 Keir, Gardener's Cottage 0.26 Land Scottish Lowlands Land at Croy 122.00 Other Tay Rannoch School, Kinloch 0.00 Land West Argyll Land at Killean, By Inverary 0.00 Other West Argyll Visibility Splay at Killean 0.00 2005/2006 TOTAL AREA ACQUIRED 9752.36 TOTAL EXPENDITURE £ 3,143,260.00 Bldgs & Ld Cowal & Trossachs Access Variation, Ormidale & South Otter 0.00 Bldgs & Ld Dumfries & Borders 4 Eshiels 0.18 Bldgs & Ld Galloway Craigencolon Access 0.00 Forest Inverness, Ross & Skye 1 Highlander Way 0.27 Forest Lochaber Chapman's Wood 164.60 Forest Moray & Aberdeenshire South Balnoon 130.00 Land Moray & Aberdeenshire Access Servitude, Raefin Farm, Fochabers 0.00 Land North Highland Auchow, Rumster 16.23 Land North Highland Water Pipe Servitude, No 9 Borgie 0.00 Land Scottish Lowlands East Grange 216.42 Land Scottish Lowlands Tulliallan 81.00 Land Scottish Lowlands Wester Mosshat (Horberry) (Lease) 101.17 Other Scottish Lowlands Cochnohill (1 & 2) 556.31 Other Scottish Lowlands Knockmountain 197.00 Other Tay Land at Blackcraig Farm, Blairgowrie -

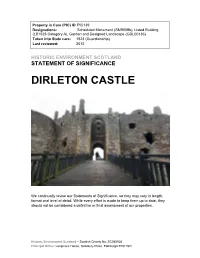

Dirleton Castle

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC 139 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM90096), Listed Building (LB1525 Category A), Garden and Designed Landscape (GDL00136) Taken into State care: 1923 (Guardianship) Last reviewed: 2012 HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT SCOTLAND STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE DIRLETON CASTLE We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH DIRLETON CASTLE SYNOPSIS Dirleton Castle, in the heart of the pretty East Lothian village of that name, is one of Scotland's oldest masonry castles. Built around the middle of the 13th century, it remained a noble residence for four centuries. Three families resided there, and each has left its mark on the fabric – the de Vauxs (13th century – the cluster of towers at the SW corner), the Haliburtons (14th/15th century – the entrance gatehouse and east range) and the Ruthvens (16th century – the Ruthven Lodging, dovecot and gardens). The first recorded siege of Dirleton Castle was in 1298, during the Wars of Independence with England. The last occurred in 1650, following Oliver Cromwell’s invasion. However, Dirleton was primarily a residence of lordship, not a garrison stronghold, and the complex of buildings that we see today conveys clearly how the first castle was adapted to suit the changing needs and fancies of their successors. -

Foi-17-02802

Annex B Deputy First Minister’s briefing for James Wolffe meeting on 3 March 2016: Meeting with James Wolffe QC, Dean of Faculty of Advocates 14:30, 3 March 2016 Key message Support efforts to improve the societal contribution made by the courts. In particular the contribution to growing the economy Who James Wolffe QC, Dean of Faculty of Advocates What Informal meeting, principally to listen to the Dean’s views and suggestions Where Parliament When Date Thursday 3 March 2016 Time 14:30 pm Supporting Private Office indicated no officials required officials Briefing and No formal agenda agenda Annex A: Background on Faculty and biography of Mr Wolffe Annex B: Key lines Annex C: Background issues Copy to: Cabinet Secretary for Justice Minister for Community Safety and Legal Affairs DG Learning and Justice DG Enterprise, Environment and Innovation Neil Rennick, Director Justice Jan Marshall [REDACTED] Nicola Wisdahl Cameron Stewart [REDACTED] John McFarlane, Special Adviser Communications Safer & Stronger St Andrew’s House, Regent Road, Edinburgh EH1 3DG www.scotland.gov.uk MEETING WITH JAMES WOLFFE QC ANNEX A Background The Faculty of Advocates is an independent body of lawyers who have been admitted to practise as Advocates before the Courts of Scotland. The Faculty has been in existence since 1532 when the College of Justice was set up by Act of the Scots Parliament, but its origins are believed to predate that event. It is self- regulating, and the Court delegates to the Faculty the task of preparing Intrants for admission as Advocates. This task involves a process of examination and practical instruction known as devilling, during which Intrants benefit from intensive structured training in the special skills of advocacy. -

Post-Office Annual Directory

frt). i pee Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/postofficeannual182829edin n s^ 'v-y ^ ^ 9\ V i •.*>.' '^^ ii nun " ly Till [ lililiiilllliUli imnw r" J ifSixCtitx i\ii llatronase o( SIR DAVID WEDDERBURN, Bart. POSTMASTER-GENERAL FOR SCOTLAND. THE POST OFFICE ANNUAL DIRECTORY FOR 18^8-29; CONTAINING AN ALPHABETICAL LIST OF THE NOBILITY, GENTRY, MERCHANTS, AND OTHERS, WITH AN APPENDIX, AND A STREET DIRECTORY. TWENTY -THIRD PUBLICATION. EDINBURGH : ^.7- PRINTED FOR THE LETTER-CARRIERS OF THE GENERAL POST OFFICE. 1828. BALLAN'fVNK & CO. PRINTKBS. ALPHABETICAL LIST Mvtt% 0quaxt&> Pates, kt. IN EDINBURGH, WITH UEFERENCES TO THEIR SITUATION. Abbey-Hill, north of Holy- Baker's close, 58 Cowgate rood Palace BaUantine's close, 7 Grassmrt. Abercromby place, foot of Bangholm, Queensferry road Duke street Bangholm-bower, nearTrinity Adam square. South Bridge Bank street, Lawnmarket Adam street, Pleasance Bank street, north, Mound pi. Adam st. west, Roxburgh pi. to Bank street Advocate's close, 357 High st. Baron Grant's close, 13 Ne- Aird's close, 139 Grassmarket ther bow Ainslie place, Great Stuart st. Barringer's close, 91 High st. Aitcheson's close, 52 West port Bathgate's close, 94 Cowgate Albany street, foot of Duke st. Bathfield, Newhaven road Albynplace, w.end of Queen st Baxter's close, 469 Lawnmar- Alison's close, 34 Cowgate ket Alison's square. Potter row Baxter's pi. head of Leith walk Allan street, Stockbridge Beaumont place, head of Plea- Allan's close, 269 High street sance and Market street Bedford street, top of Dean st.