Pan Troglodytes, Chimpanzee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

10 Sota3 Chapter 7 REV11

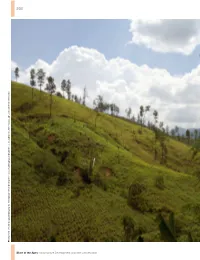

200 Until recently, quantifying rates of tropical forest destruction was challenging and laborious. © Jabruson 2017 (www.jabruson.photoshelter.com) forest quantifying rates of tropical Until recently, Photo: State of the Apes Infrastructure Development and Ape Conservation 201 CHAPTER 7 Mapping Change in Ape Habitats: Forest Status, Loss, Protection and Future Risk Introduction This chapter examines the status of forested habitats used by apes, charismatic species that are almost exclusively forest-dependent. With one exception, the eastern hoolock, all ape species and their subspecies are classi- fied as endangered or critically endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) (IUCN, 2016c). Since apes require access to forested or wooded land- scapes, habitat loss represents a major cause of population decline, as does hunting in these settings (Geissmann, 2007; Hickey et al., 2013; Plumptre et al., 2016b; Stokes et al., 2010; Wich et al., 2008). Until recently, quantifying rates of trop- ical forest destruction was challenging and laborious, requiring advanced technical Chapter 7 Status of Apes 202 skills and the analysis of hundreds of satel- for all ape subspecies (Geissmann, 2007; lite images at a time (Gaveau, Wandono Tranquilli et al., 2012; Wich et al., 2008). and Setiabudi, 2007; LaPorte et al., 2007). In addition, the chapter projects future A new platform, Global Forest Watch habitat loss rates for each subspecies and (GFW), has revolutionized the use of satel- uses these results as one measure of threat lite imagery, enabling the first in-depth to their long-term survival. GFW’s new analysis of changes in forest availability in online forest monitoring and alert system, the ranges of 22 great ape and gibbon spe- entitled Global Land Analysis and Dis- cies, totaling 38 subspecies (GFW, 2014; covery (GLAD) alerts, combines cutting- Hansen et al., 2013; IUCN, 2016c; Max Planck edge algorithms, satellite technology and Insti tute, n.d.-b). -

Identification of Subspecies and Parentage Relationship by Means of DNA Fingerprinting in Two Exemplary of Pan Troglodytes (Blumenbach, 1775) (Mammalia Hominidae)

Biodiversity Journal , 2018, 9 (2): 107–114 DOI: 10.31396/Biodiv.Jour.2018.9.2.107.114 Identification of subspecies and parentage relationship by means of DNA fingerprinting in two exemplary of Pan troglodytes (Blumenbach, 1775) (Mammalia Hominidae) Viviana Giangreco 1, Claudio Provito 1, Luca Sineo 2, Tiziana Lupo 1, Floriana Bonanno 1 & Stefano Reale 1* 1Istituto Zooprofilattico Sperimentale della Sicilia “A. Mirri”, Via G. Marinuzzi 3, 90129 Palermo, Italy 2Biologia animale e Antropologia, Dip. STEBICEF, Via Archirafi 18, 90123 Palermo, Italy *Corresponding author, e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Four chimpanzee subspecies (Mammalia Hominidae) are commonly recognised: the West - ern Chimpanzee, P. troglodytes verus (Schwarz, 1934), the Nigeria-Cameroon Chim - panzee, P. troglodytes ellioti, the Central Chimpanzee, P. troglodytes troglodytes (Blumenbach, 1799), and the Eastern Chimpanzee, P. troglodytes schweinfurthii (Giglioli, 1872). Recent studies on mitochondrial DNA show the incorporation of P. troglodytes schweinfurthii in P. troglodytes troglodytes , suggesting the existence of only two sub - species: P. troglodytes troglodytes in Central and Eastern Africa and P. troglodytes verus- P. troglodytes ellioti in West Africa. The aim of the present study is twofold: first, to identify the correct subspecies of two chimpanzee samples collected in a Biopark structure in Carini (Sicily, Italy), and second, to verify whether there was a kinship relationship be - tween the two samples through techniques such as DNA barcoding and microsatellite analysis. DNA was extracted from apes’ buccal swabs, the cytochrome oxidase subunit 1 (COI) gene was amplified using universal primers, then purified and injected into capillary electrophoresis Genetic Analyzer ABI 3130 for sequencing. The sequence was searched on the NCBI Blast database. -

Ebola & Great Apes

Ebola & Great Apes Ebola is a major threat to the survival of African apes There are direct links between Ebola outbreaks in humans and the contact with infected bushmeat from gorillas and chimpanzees. In the latest outbreak in West Africa, Ebola claimed more than 11,000 lives, but the disease has also decimated great ape populations during previous outbreaks in Central Africa. What are the best strategies for approaching zoonotic diseases like Ebola to keep both humans and great apes safe? What is Ebola ? Ebola Virus Disease, formerly known as Ebola Haemorrhagic Fever, is a highly acute, severe, and lethal disease that can affect humans, chimpanzees, and gorillas. It was discovered in 1976 in the Democratic Republic of Congo and is a Filovirus, a kind of RNA virus that is 50-100 times smaller than bacteria. • The initial symptoms of Ebola can include a sudden fever, intense weakness, muscle pain and a sore throat, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). Subsequent stages include vomiting, diarrhoea and, in some cases, both internal and external bleeding. • Though it is believed to be carried in bat populations, the natural reservoir of Ebola is unknown. A reservoir is the long-term host of a disease, and these hosts often do not contract the disease or do not die from it. • The virus is transmitted to people from wild animals through the consumption and handling of wild meats, also known as bushmeat, and spreads in the human population via human-to-human transmission through contact with bodily fluids. • The average Ebola case fatality rate is around 50%, though case fatality rates have varied from 25% to 90%. -

Proposal for Inclusion of the Chimpanzee

CMS Distribution: General CONVENTION ON MIGRATORY UNEP/CMS/COP12/Doc.25.1.1 25 May 2017 SPECIES Original: English 12th MEETING OF THE CONFERENCE OF THE PARTIES Manila, Philippines, 23 - 28 October 2017 Agenda Item 25.1 PROPOSAL FOR THE INCLUSION OF THE CHIMPANZEE (Pan troglodytes) ON APPENDIX I AND II OF THE CONVENTION Summary: The Governments of Congo and the United Republic of Tanzania have jointly submitted the attached proposal* for the inclusion of the Chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) on Appendix I and II of CMS. *The geographical designations employed in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the CMS Secretariat (or the United Nations Environment Programme) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The responsibility for the contents of the document rests exclusively with its author. UNEP/CMS/COP12/Doc.25.1.1 PROPOSAL FOR THE INCLUSION OF CHIMPANZEE (Pan troglodytes) ON APPENDICES I AND II OF THE CONVENTION ON THE CONSERVATION OF MIGRATORY SPECIES OF WILD ANIMALS A: PROPOSAL Inclusion of Pan troglodytes in Appendix I and II of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals. B: PROPONENTS: Congo and the United Republic of Tanzania C: SUPPORTING STATEMENT 1. Taxonomy 1.1 Class: Mammalia 1.2 Order: Primates 1.3 Family: Hominidae 1.4 Genus, species or subspecies, including author and year: Pan troglodytes (Blumenbach 1775) (Wilson & Reeder 2005) [Note: Pan troglodytes is understood in the sense of Wilson and Reeder (2005), the current reference for terrestrial mammals used by CMS). -

The Evolutionary History of Human and Chimpanzee Y-Chromosome Gene Loss

The Evolutionary History of Human and Chimpanzee Y-Chromosome Gene Loss George H. Perry,* à Raul Y. Tito,* and Brian C. Verrelli* *Center for Evolutionary Functional Genomics, The Biodesign Institute, Arizona State University, Tempe; School of Life Sciences, Arizona State University, Tempe; and àSchool of Human Evolution and Social Change, Arizona State University, Tempe Recent studies have suggested that gene gain and loss may contribute significantly to the divergence between humans and chimpanzees. Initial comparisons of the human and chimpanzee Y-chromosomes indicate that chimpanzees have a dis- proportionate loss of Y-chromosome genes, which may have implications for the adaptive evolution of sex-specific as well as reproductive traits, especially because one of the genes lost in chimpanzees is critically involved in spermatogenesis in humans. Here we have characterized Y-chromosome sequences in gorilla, bonobo, and several chimpanzee subspecies for 7 chimpanzee gene–disruptive mutations. Our analyses show that 6 of these gene-disruptive mutations predate chimpan- zee–bonobo divergence at ;1.8 MYA, which indicates significant Y-chromosome change in the chimpanzee lineage Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/mbe/article/24/3/853/1246230 by guest on 23 September 2021 relatively early in the evolutionary divergence of humans and chimpanzees. Introduction The initial comparisons of human and chimpanzee Comparative analyses of single-nucleotide differences (Pan troglodytes) Y-chromosome sequences revealed that between human and chimpanzee genomes typically show although there are no lineage-specific gene-disruptive mu- estimates of approximately 1–2% divergence (Watanabe tations in the X-degenerate portion of the Y-chromosome et al. 2004; Chimpanzee Sequencing and Analysis Consor- fixed within humans, surprisingly, 4 genes, CYorf15B, tium 2005). -

Tanzania Chimpanzee Conservation Action Plan 2018-2023

Tanzania Chimpanzee Conservation Action Plan 2018-2023 This plan is written in collaboration with various institutions that have interest and are working tirelessly in conserving chimpanzees in Tanzania. Editorial list i. Dr. Edward Kohi ii. Dr. Julius Keyyu iii. Dr. Alexander Lobora iv. Ms. Asanterabi Kweka v. Dr. Iddi Lipembe vi. Dr. Shadrack Kamenya vii. Dr. Lilian Pintea viii. Dr. Deus Mjungu ix. Dr. Nick Salafsky x. Dr. Flora Magige xi. Dr. Alex Piel xii. Ms. Kay Kagaruki xiii. Ms. Blanka Tengia xiv. Mr. Emmanuel Mtiti Published by: Tanzania Wildlife Research Institute (TAWIRI) Citation: TAWIRI (2018) Tanzania Chimpanzee Conservation Action Plan 2018-2023 TAWIRI Contact: [email protected] Cover page photo: Chimpanzee in Mahale National Park, photo by Simula Maijo Peres ISBN: 978-9987-9567-53 i Acknowledgements On behalf of the Ministry of Natural Resource and Tourism (MNRT), Wildlife Division (WD), Tanzania National Parks (TANAPA), and Tanzania Wildlife Authority (TAWA), the Tanzania Wildlife Research Institute (TAWIRI) wishes to express its gratitude to organizations and individuals who contributed to the development of this plan. We acknowledge the financial support from the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and the U.S Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) for the planning process. Special thanks are extended to the Jane Goodall Institute (JGI) and Kyoto University for their long-term chimpanzee research in the country that has enhanced our understanding of the species behaviour, biology and ecology, thereby greatly contributing to the development process of this conservation action plan. TAWIRI also wishes to acknowledge contributions by Conservation Breeding Specialist Group - Species Survival Commission of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), Evaluation and Research Technologies for Health, Inc. -

February1 19 Heterochromatin Sup Tables

Table S1. Data used in this study. The individual number of reads for each data file (after filtering) are available in the repository file “rcounts”. number of Sample Sample libraries Species M:F* Subspecies M:F* insert size size size (technical replicates) Diverse human populations from HGDP 9 9:0 9 Human (Homo sapiens) 18 14:4 Families of human trios 9 5:4 9 Nigeria-Cameroon chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes ellioti)4 1:3 4 200-233 Eastern chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii) 6 2:4 35 212-507 Central chimpanzee(Pan troglodytes troglodytes) 4 1:3 19 434-501 Western chimpanzee(Pan troglodytes verus) 4 3:1 21 211-492 Chimpanzee(Pan troglodytes) 19 10:9 Hybrid of Western and Central chimpanzee(Pan troglodytes1 verus/troglodytes)1:0 4 214-387 Bonobo (Pan paniscus) 13 2:11 Bonobo (Pan paniscus) 69 532 Eastern lowland gorilla Gorilla (Gorilla) 27 6:21 (Gorilla beringei graueri) 3 2:1 18 472 Cross river gorilla(Gorilla gorilla diehli) 1 0:1 4 450 Western lowland gorilla(Gorilla gorilla gorilla) 23 4:19 82 522 Sumatran orangutan (Pongo abelii) 5 1:4 Sumatran orangutan(Pongo abelii) 5 1:4 24 460-506 Bornean orangutan(Pongo pygmaeus) 5 1:4 Bornean orangutan(Pongo pygmaeus) 5 1:4 15 463-503 * M:F represents the ratio of males to females. Human trios Source amplification Read length sequencer Son77 family Illumina platinumPCR- 101 HiSeq2000 Daughter78 family Illumina platinumPCR- 101 HiSeq2000 Ashkenazi family GIAB PCR- 150 trimmed to 100 HiSeq2500 Table S2. 39 abundant repeated motifs. List of repeated motifs that are potential derivatives List -

West African Chimpanzees

Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan West African Chimpanzees Compiled and edited by Rebecca Kormos, Christophe Boesch, Mohamed I. Bakarr and Thomas M. Butynski IUCN/SSC Primate Specialist Group IUCN The World Conservation Union Donors to the SSC Conservation Communications Programme and West African Chimpanzees Action Plan The IUCN Species Survival Commission is committed to communicating important species conservation information to natural resource managers, decision makers and others whose actions affect the conservation of biodiversity. The SSC’s Action Plans, Occasional Papers, newsletter Species and other publications are supported by a wide variety of generous donors including: The Sultanate of Oman established the Peter Scott IUCN/SSC Action Plan Fund in 1990. The Fund supports Action Plan development and implementation. To date, more than 80 grants have been made from the Fund to SSC Specialist Groups. The SSC is grateful to the Sultanate of Oman for its confidence in and support for species conservation worldwide. The Council of Agriculture (COA), Taiwan has awarded major grants to the SSC’s Wildlife Trade Programme and Conser- vation Communications Programme. This support has enabled SSC to continue its valuable technical advisory service to the Parties to CITES as well as to the larger global conservation community. Among other responsibilities, the COA is in charge of matters concerning the designation and management of nature reserves, conservation of wildlife and their habitats, conser- vation of natural landscapes, coordination of law enforcement efforts, as well as promotion of conservation education, research, and international cooperation. The World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) provides significant annual operating support to the SSC. -

Behavior on Tour and Non-Tour Days at Chimpanzee Sanctuary Northwest

Central Washington University ScholarWorks@CWU All Master's Theses Master's Theses Spring 2016 Comparison of Chimpanzee (Pan Troglodytes) Behavior on Tour and Non-Tour Days at Chimpanzee Sanctuary Northwest Allison A. Farley Central Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/etd Part of the Animal Sciences Commons, and the Other Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Farley, Allison A., "Comparison of Chimpanzee (Pan Troglodytes) Behavior on Tour and Non-Tour Days at Chimpanzee Sanctuary Northwest" (2016). All Master's Theses. 425. https://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/etd/425 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses at ScholarWorks@CWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@CWU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMPARISON OF CHIMPANZEE (PAN TROGLODYTES) BEHAVIOR ON TOUR AND NON-TOUR DAYS AT CHIMPANZEE SANCTUARY NORTHWEST __________________________________ A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty Central Washington University __________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science Primate Behavior and Ecology ___________________________________ by Allison Ann Farley May 2016 CENTRAL WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY Graduate Studies We hereby approve the thesis of Allison Ann Farley Candidate for the degree of Master of Science APPROVED FOR THE GRADUATE FACULTY ______________ _________________________________________ -

African Great Apes Update

African Great Apes Update Recent News from the WWF African Great Apes Programme © WWF / PJ Stephenson Number 1 – January 2005 Cover photo: Project staff from the Wildlife Conservation Society marking a Cross River gorilla nest in the proposed gorilla sanctuary at Kagwene, Mbulu Hills, Cameroon (see story on page 7). This edition of African Great Apes Update was edited by PJ Stephenson. The content was compiled by PJ Stephenson & Alison Wilson. African Great Apes Update provides recent news on the conservation work funded by the WWF African Great Apes Programme. It is aimed at WWF staff and WWF's partners such as range state governments, international and national non-governmental organizations, and donors. It will be published at least once per year. Published in January 2005 by WWF - World Wide Fund for Nature (formerly World Wildlife Fund), CH-1196, Gland, Switzerland Any reproduction in full or in part of this publication must mention the title and credit the above-mentioned publisher as the copyright owner. No photographs from this publication may be reproduced on the internet without prior authorization from WWF. The material and the geographical designations in this report do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of WWF concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. © text 2005 WWF All rights reserved In 2002, WWF launched a new African Great Apes Programme to respond to the threats facing chimpanzees, bonobos, and western and eastern gorillas. Building on more than 40 years of experience in great ape conservation, WWF’s new initiative aims to provide strategic field interventions to help guarantee a future for these threatened species. -

The Sampling Scheme Matters: Pan Troglodytes Troglodytes and P

AMERICAN JOURNAL OF PHYSICAL ANTHROPOLOGY 156:181–191 (2015) The Sampling Scheme Matters: Pan troglodytes troglodytes and P. t. schweinfurthii Are Characterized by Clinal Genetic Variation Rather Than a Strong Subspecies Break Tillmann Funfst€ uck,€ 1* Mimi Arandjelovic,1 David B. Morgan,2 Crickette Sanz,3 Patricia Reed,2 Sarah H. Olson,2 Ken Cameron,2 Alain Ondzie,4 Martine Peeters,5 and Linda Vigilant1* 1Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Deutscher Platz 6, 04103 Leipzig, Germany 2Wildlife Conservation Society, Global Conservation, 2300 Southern Boulevard, New York, NY 10460, USA 3Department of Anthropology, Washington University, 1 Brookings Drive, Saint Louis, MO 63130, USA 4Wildlife Conservation Society, Congo Program, 151 Ave Charles de Gaulle, Brazzaville, Republic of Congo 5UMI233, TransVIHMI, Institut de Recherche pour le Developpement (IRD) and Universite Montpellier 1, Montpel- lier, France KEY WORDS genetic differentiation; isolation by distance; structure; microsatellites; genotyping ABSTRACT Populations of an organism living in were sampled across large parts of their range and analyzed marked geographical or evolutionary isolation from other them together with 283 published eastern chimpanzee geno- populations of the same species are often termed subspecies types from known localities. We observed a clear signal of and expected to show some degree of genetic distinctiveness. isolation by distance across both subspecies. Further, we Thecommonchimpanzee(Pan troglodytes) is currently found that a large proportionofcomparisonsbetween described as four geographically delimited subspecies: the groups taken from the same subspecies showed higher western (P. t. verus), the nigerian-cameroonian (P. t. ellioti), genetic differentiation than the least differentiated the central (P. t. troglodytes) and the eastern (P. -

The Critically Endangered Western Chimpanzee Declines by 80%

Received: 10 February 2017 | Revised: 9 May 2017 | Accepted: 3 June 2017 DOI: 10.1002/ajp.22681 RESEARCH ARTICLE The Critically Endangered western chimpanzee declines by 80% Hjalmar S. Kühl1,2 | Tenekwetsche Sop1,2 | Elizabeth A. Williamson3 | Roger Mundry1 | David Brugière4 | Genevieve Campbell5 | Heather Cohen1 | Emmanuel Danquah6 | Laura Ginn7 | Ilka Herbinger8 | Sorrel Jones9,10 | Jessica Junker1 | Rebecca Kormos11 | Celestin Y. Kouakou12,13,14 | Paul K. N’Goran15 | Emma Normand12 | Kathryn Shutt-Phillips16 | Alexander Tickle1 | Elleni Vendras1,17 | Adam Welsh1 | Erin G. Wessling1 | Christophe Boesch1,12 1 Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig, Germany 2 German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv), Halle-Jena-Leipzig, Leipzig, Germany 3 Faculty of Natural Sciences, University of Stirling, Scotland, UK 4 Projets Biodiversité et Ressources Naturelles BRL Ingénierie, Nimes Cedex, France 5 The Biodiversity Consultancy Ltd, Cambridge, UK 6 Department of Wildlife and Range Management, Faculty of Renewable Natural Resources, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana 7 Anthropology Centre for Conservation, Environment and Development, Oxford Brookes University, Oxford, UK 8 WWF Germany, Berlin, Germany 9 RSPB Centre for Conservation Science, The Lodge, Sandy, Beds, UK 10 Royal Holloway University of London, Egham Hill, Egham, UK 11 Department of Integrative Biology, University of California, Berkeley, California 12 Wild Chimpanzee Foundation, Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire 13 Université Jean Lorougnon Guédé, Daloa, Côte d’Ivoire 14 Centre Suisse de Recherches Scientifiques en Côte d’Ivoire, Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire 15 WWF International Regional Office for Africa, Yaoundé, Cameroon 16 Fauna and Flora International, David Attenborough Building, Cambridge, UK 17 Regional Environmental Center for Eastern and Central Europe, Warsaw, Poland Correspondence African large mammals are under extreme pressure from unsustainable hunting and Hjalmar S.