Through Rocl<Y Reach

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bald Eagle Wintering Activity Rocky Reach Reservoir

Bald Eagle Wintering Activity Summary, 2011 - 2012 Bald Eagle Wintering Activity Rocky Reach Reservoir 2011 - 2012 Public Utility District No. 1 of Chelan County Fish & Wildlife Department Wenatchee, WA 98807-1231 Bald Eagle Wintering Activity Summary, 2011 - 2012 INTRODUCTION The Public Utility District No. 1 of Chelan County (Chelan PUD) owns and operates the Rocky Reach Hydroelectric Project along the Columbia River in central Washington. This project operates under Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) license #2145-060. Rocky Reach Dam was licensed in 1957 and began generating electricity in 1961. The operating license was renewed in 2009. As prescribed in the Rocky Reach Wildlife Habitat Management Plan required by Article 403 of the Rocky Reach license, Chelan PUD continues to monitor numbers of wintering eagles along Rocky Reach Reservoir (Chelan PUD 2010). This annual report summarizes data collected on wintering bald eagles for the winter of 2011 - 2012. HISTORY From 1975 – 1984, the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) conducted monthly aerial surveys for wintering bald eagles along the mid-Columbia River, including Rocky Reach Reservoir (Fielder and Starkey 1980). In 1985, Chelan PUD began regularly monitoring eagles during the winter months along Rocky Reach Reservoir. The bald eagle was delisted on August 9, 2007. As a result, Chelan PUD reduced the monitoring effort from weekly to monthly during the winter months (November – March). This frequency of monitoring exceeds the level suggested in the bald eagle post-delisting monitoring plan (USFWS 2009) and should provide sufficient trend information into the future. Winter surveys allow Chelan PUD to determine distribution of wintering eagles along the Reservoir and to determine the age ratio of sub-adults: adults. -

2009 Rocky Reach and Rocky Island Fish Passage Plan, Article 402, 03

March 30, 2009 To: Bryan Nordlund National Marine Fisheries Service 510 Desmond Drive SE, Suite 103 Lacey, WA 98503 Dear Mr. Nordlund, Public Utility District No.1 of Chelan County (Chelan) respectfully submits this final 2009 Fish Passage Plan (FPP). The section pertaining to the Rocky Reach Hydroelectric Project, FERC No. 2145, is submitted in accordance with License Article No. 408 of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) Order, issued April 12, 2002, amending the license for the Rocky Reach project authorizing the installation of a permanent juvenile fish bypass system. On February 19, 2009, FERC issued a new 43-year operating license for the Rocky Reach Project. Article 402 of the new license requires that …. “Within six months of the issuance date of license and by February 15 each year thereafter, the licensee shall file for Commission approval an operations plan.” The purpose of the new annual Rocky Reach operations plan, we believe, will be to supplant the former FPP, requiring all of the current reporting contents of that plan, but may also require additional information on fisheries and water-quality-related criteria and protocols. Please contact me with any questions or concerns that you might have. Respectfully yours, Barry G. Keesee Fisheries Studies Coordinator (509) 661-4763 Rocky Reach and Rock Island Fish Passage Plan 2009 Final Prepared by Thaddeus R. Mosey Steve L. Hemstrom Barry G. Keesee Fish and Wildlife Department Public Utility District No. 1 of Chelan County Wenatchee, WA 98801 March 31, 2009 Table of Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………………. 1 Overview…………………………………………………………………… 1 Emergency Deviations from the Fish Passage Plan (FPP)………………… 1 Spill…………………………………………………………………………. -

Chief Joseph Hatchery Program

Chief Joseph Hatchery Program Draft Environmental Impact Statement DOE/EIS-0384 May 2007 Chief Joseph Hatchery Program Responsible Agency: U.S. Department of Energy, Bonneville Power Administration (BPA) Title of Proposed Project: Chief Joseph Hatchery Program Cooperating Tribe: Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation State Involved: Washington Abstract: The Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS) describes a Chinook salmon hatchery production program sponsored by the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation (Colville Tribes). BPA proposes to fund the construction, operation and maintenance of the program to help mitigate for anadromous fish affected by the Federal Columbia River Power System dams on the Columbia River. The Colville Tribes want to produce adequate salmon to sustain tribal ceremonial and subsistence fisheries and enhance the potential for a recreational fishery for the general public. The DEIS discloses the environmental effects expected from facility construction and program operations and a No Action alternative. The Proposed Action is to build a hatchery near the base of Chief Joseph Dam on the Columbia River for incubation, rearing and release of summer/fall and spring Chinook. Along the Okanogan River, three existing irrigation ponds, one existing salmon acclimation pond, and two new acclimation ponds (to be built) would be used for final rearing, imprinting and volitional release of chinook smolts. The Chief Joseph Dam Hatchery Program Master Plan (Master Plan, Northwest Power and Conservation Council, May 2004) provides voluminous information on program features. The US Army Corps of Engineers, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission, Oroville-Tonasket Irrigation District, and others have cooperated on project design and siting. -

Regional Pacific Lamprey Workshop Mtg Minutes 060816

Final Regional Pacific Lamprey Workshop Minutes To: Aquatic SWG Parties Date: July 12, 2016 From: Kristi Geris (Anchor QEA, LLC) Re: Final Minutes of the Regional Pacific Lamprey Workshop The Regional Pacific Lamprey Workshop was held at Douglas PUD headquarters in East Wenatchee, Washington, on Wednesday, June 8, 2016, from 9:00 a.m. to 2:30 p.m. Attendees are listed in Attachment A of these workshop minutes. I. Summary of Discussions 1. Welcome, Introductions, and Workshop Goals (John Ferguson): John Ferguson (Aquatic Settlement Work Group [SWG] Chairman) welcomed the attendees (attendees are listed in Attachment A) and opened the meeting. Ferguson said the purpose for this Regional Pacific Lamprey Workshop is to address scientific uncertainties regarding the causes of poor adult Pacific lamprey passage over Wells Dam and to facilitate regional collaboration in addressing Pacific Lamprey in the Mid‐Columbia River Basin. Ferguson said the goals of today’s workshop include: 1) identifying critical uncertainties that need resolution; 2) discussing and possibly adjusting 2016 Pacific lamprey study designs for Wells and Rocky Reach reservoirs; 3) establishing the scientific foundation for longer term studies; 4) partitioning out adult Pacific lamprey presence and premature mortality; 5) determining more accurate passage enumeration and efficiencies; 6) aiding the prioritization of available study fish; and 7) beginning development of a more integrated approach to Pacific lamprey passage investigations at Mid‐Columbia River dams. Ferguson said today is the first of several discussions aimed at improving the Pacific lamprey resource within the respective jurisdictions of Grant, Chelan, and Douglas PUDs. He indicated the focus of today’s workshop is passage through the Rocky Reach Reservoir and Wells Dam; the Aquatic SWG will focus on fish exiting Wells Dam and migrating through the Wells Reservoir at future meetings. -

Dams and Hydroelectricity in the Columbia

COLUMBIA RIVER BASIN: DAMS AND HYDROELECTRICITY The power of falling water can be converted to hydroelectricity A Powerful River Major mountain ranges and large volumes of river flows into the Pacific—make the Columbia precipitation are the foundation for the Columbia one of the most powerful rivers in North America. River Basin. The large volumes of annual runoff, The entire Columbia River on both sides of combined with changes in elevation—from the the border is one of the most hydroelectrically river’s headwaters at Canal Flats in BC’s Rocky developed river systems in the world, with more Mountain Trench, to Astoria, Oregon, where the than 470 dams on the main stem and tributaries. Two Countries: One River Changing Water Levels Most dams on the Columbia River system were built between Deciding how to release and store water in the Canadian the 1940s and 1980s. They are part of a coordinated water Columbia River system is a complex process. Decision-makers management system guided by the 1964 Columbia River Treaty must balance obligations under the CRT (flood control and (CRT) between Canada and the United States. The CRT: power generation) with regional and provincial concerns such as ecosystems, recreation and cultural values. 1. coordinates flood control 2. optimizes hydroelectricity generation on both sides of the STORING AND RELEASING WATER border. The ability to store water in reservoirs behind dams means water can be released when it’s needed for fisheries, flood control, hydroelectricity, irrigation, recreation and transportation. Managing the River Releasing water to meet these needs influences water levels throughout the year and explains why water levels The Columbia River system includes creeks, glaciers, lakes, change frequently. -

Rocky Reach Pacific Lamprey Management Plan

ROCKY REACH PACIFIC LAMPREY MANAGEMENT PLAN Final Draft ROCKY REACH HYDROELECTRIC PROJECT FERC Project No. 2145 September 623, 2005 Public Utility District No. 1 of Chelan County Wenatchee, Washington Pacific Lamprey Management Plan TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................................................1 SECTION 1: INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................................................3 SECTION 2: BACKGROUND..............................................................................................................................4 2.1 Life History ....................................................................................................................................................4 2.2 Species Status.................................................................................................................................................4 2.3 Adult Fishway Counts....................................................................................................................................4 2.4 Spawning and Rearing ...................................................................................................................................5 SECTION 3: STUDIES AND EVALUATION OF PROJECT EFFECTS........................................................6 3.1 Adult Lamprey Telemetry Study....................................................................................................................6 -

Rocky Reach Dam: Operational and Structural Total Dissolved Gas Management

Rocky Reach Dam: Operational and Structural Total Dissolved Gas Management by Michael L. Schneider and Steven C. Wilhelms U.S. Army Engineer Research and Development Center 3909 Halls Ferry Road Vicksburg, MS 39180 For Chelan County Public Utility District No. 1 327 N. Wenatchee Ave., PO Box 1231 Wenatchee, WA 98807 Table of Contents Table of Contents............................................................................................................2 List of Tables ..................................................................................................................3 Preface............................................................................................................................6 Background.....................................................................................................................7 Objective.........................................................................................................................7 Approach ........................................................................................................................7 Project Description..........................................................................................................9 General TDG Exchange Description.......................................................................... 10 Forebay ................................................................................................................. 11 Spillway............................................................................................................... -

NMFS National Marine Fisheries Service

20120307-5193 FERC PDF (Unofficial) 3/7/2012 4:54:15 PM 20120307-5193 FERC PDF (Unofficial) 3/7/2012 4:54:15 PM 20120307-5193 FERC PDF (Unofficial) 3/7/2012 4:54:15 PM 20120307-5193 FERC PDF (Unofficial) 3/7/2012 4:54:15 PM 20120307-5193 FERC PDF (Unofficial) 3/7/2012 4:54:15 PM Table of Contents LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................................................... 4 LIST OF TABLES ........................................................................................................................ 5 TERMS AND ABBREVIATIONS .............................................................................................. 6 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................... 11 1.1 BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................................................ 11 1.2 CONSULTATION HISTORY .................................................................................................................................. 11 1.3 PROPOSED ACTION .......................................................................................................................................... 11 1.4 ACTION AREA ................................................................................................................................................. 12 2. ENDANGERED SPECIES ACT: BIOLOGICAL OPINION AND INCIDENTAL TAKE STATEMENT ................................................................................................................ -

Wells Hydroelectric Project Total Dissolved Gas Abatement Plan 2013 Annual Report

Wells Hydroelectric Project Total Dissolved Gas Abatement Plan 2013 Annual Report Public Utility District No. 1 of Douglas County 1151 Valley Mall Parkway East Wenatchee, WA 98802-4331 Prepared for: Pat Irle Hydropower Projects Manager Washington Department of Ecology 15 W. Yakima Avenue, Suite 200 Yakima, WA 98902-3452 January 2013 This page intentionally left blank TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Project Description ........................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Fixed Monitoring Site Locations .................................................................................................... 1 1.3 Regulatory Framework .................................................................................................................. 2 1.4 2013 Gas Abatement Plan Approach ............................................................................................ 3 1.4.1 Operational ........................................................................................................................... 3 1.4.2 Structural ............................................................................................................................... 3 1.4.3 Consultation .......................................................................................................................... 4 2 OPERATIONS ........................................................................................................... -

Rock Island Land Management Plan

A guide to Chelan PUD’s program for managing the lands and shorelines within the Rock Island Hydroelectric Project Boundary ROCK ISLAND HYDROELECTRIC PROJECT FERC Project No. 943 Public Utility District No. 1 of Chelan County Wenatchee, Washington Prepared with assistance from Kleinschmidt Associates Gresham, Oregon December 2013 Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................1 6.2 Geology and Soils ........................................................35 INTRODUCTION ..............................................................3 6.3 Water Quality ..............................................................36 1.1 Project Structures, Operation, and Boundary .....................3 6.4 Aquatic Resources ........................................................37 1.2 Project Licensing History ..................................................4 6.5 Aquatic Habitat ............................................................41 1.3 FERC Regulatory Setting, Requirements 6.6 Terrestrial ....................................................................42 and Authorizations .........................................................5 6.7 Land Use .....................................................................43 1.4 Other Regulatory Jurisdictions and Management Initiatives ...................................................6 6.8 Cultural Resources ........................................................43 6.9 Recreation ...................................................................44 PURPOSE, -

Downloaded from the DRS Website At

Quincy Chute Hydroelectric Project Wanapum Dam Seattle Spokane Grant County Potholes Priest Rapids East Canal Dam Headworks Nine Canyon Wind Farm WANAPUM DAM QUINCY CHUTE HYDROELECTRIC PROJECT Generation Units . 10. Rated Capacity . 1,203.6. MW Rated Capacity . 9.4. MW Concrete/Earthfill Length . 8,637. FT First Power Generation . .1985 Rated Head . 80 FT Construction Started . .1959 First Power Generation . .1963 POTHOLES EAST CANAL HEADWORKS PROJECT PRIEST RAPIDS DAM Rated Capacity . 6.5. MW First Power Generation . .1990 Generation Units . 10. Rated Capacity . 950. MW Concrete/Earthfill Length . 10,103. FT NINE CANYON WIND PROJECT Rated Head . 78 FT Construction Started . .1956 12 .5% of Project Peak Capacity . .12 MW First Power Generation . .1959 First Power Generation . .2003 ELECTRIC SYSTEM Overhead Distribution Lines . 2,795 MILES Underground Distribution Lines . 1,102. MILES Overhead Transformers . .24,477 Padmount Transformers . 9,935 115kV Transmission Lines . 282. MILES 230kV Transmission Lines . 202. MILES ACTIVE METERS Residential . 39,103. Irrigation . 5,193 Industrial . 122 Commercial . 7,248 Large Commercial . 107 Street Light and Other . .439 Total Active Meters . 52,212. SUBSTATIONS Distribution . 49 Transmission . 5. Transmission/Distribution . 3. HIGH SPEED NETWORK Customers with fiber-optic availability . .33,149 Customers using fiber-optic service . 19,043 Customers using wireless service . 290 As of Dec. 31, 2019 Grant PUD was established by local residents in 1938 to provide power service to all of the county’s residents. We honor the resolve of our founders through our guiding vision, mission and values. VISION Excellence in service and leadership. We continually ask how we can improve service quality, reliability and stewardship of our resources in the most cost-effective manner . -

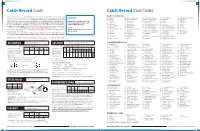

Catch Record Cards & Codes

Catch Record Cards Catch Record Card Codes The Catch Record Card is an important management tool for estimating the recreational catch of PUGET SOUND REGION sturgeon, steelhead, salmon, halibut, and Puget Sound Dungeness crab. A catch record card must be REMINDER! 824 Baker River 724 Dakota Creek (Whatcom Co.) 770 McAllister Creek (Thurston Co.) 814 Salt Creek (Clallam Co.) 874 Stillaguamish River, South Fork in your possession to fish for these species. Washington Administrative Code (WAC 220-56-175, WAC 825 Baker Lake 726 Deep Creek (Clallam Co.) 778 Minter Creek (Pierce/Kitsap Co.) 816 Samish River 832 Suiattle River 220-69-236) requires all kept sturgeon, steelhead, salmon, halibut, and Puget Sound Dungeness Return your Catch Record Cards 784 Berry Creek 728 Deschutes River 782 Morse Creek (Clallam Co.) 828 Sauk River 854 Sultan River crab to be recorded on your Catch Record Card, and requires all anglers to return their fish Catch by the date printed on the card 812 Big Quilcene River 732 Dewatto River 786 Nisqually River 818 Sekiu River 878 Tahuya River Record Card by April 30, or for Dungeness crab by the date indicated on the card, even if nothing “With or Without Catch” 748 Big Soos Creek 734 Dosewallips River 794 Nooksack River (below North Fork) 830 Skagit River 856 Tokul Creek is caught or you did not fish. Please use the instruction sheet issued with your card. Please return 708 Burley Creek (Kitsap Co.) 736 Duckabush River 790 Nooksack River, North Fork 834 Skokomish River (Mason Co.) 858 Tolt River Catch Record Cards to: WDFW CRC Unit, PO Box 43142, Olympia WA 98504-3142.