Chief Joseph Hatchery Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BRIDGEPORT STATE PARK Chief Joseph Dam, Washington

BRIDGEPORT STATE PARK Chief Joseph Dam, Washington Sun Shelter and Play Area Group Camp Fire Circle Bridgeport State Park, located on systems; landscaping; and the Columbia River at Chief Joseph sprinkler irrigation. Osborn Pacific Dam, was an existing development Group provided complete design composed of a boat launch, services followed by completion campground, temporary of bid documents for the park and administration area, and day-use recreation amenity features, and group-use areas. The park was buildings, landscape architecture, created subsequent to the Chief and sprinkler irrigation. Joseph Dam construction and was Subconsultants provided civil, Picnic Shelter built by the U.S. Army Corps of structural, mechanical, and Engineers. The park is maintained electrical engineering. Site: Approximately 400 acres of rolling and operated by Washington State arid topography on shore of Rufus Parks. Woods Lake. Approximately 30 acres Project: is developed. Osborn Pacific Group Inc. was Bridgeport State Park Services: Client: retained by the U.S. Army Corps of Final design, construction documents, US Army Corps of Engineers, Seattle and cost estimate of park and Engineers to provide design District recreation amenity features, buildings, services and prepared construction Location: landscape architecture, and sprinkler documents for a $1.4 million park Chief Joseph Dam, Columbia River, irrigation. Contract administration expansion project. Features Washington and coordination for civil, structural, mechanical, and electrical included: upgrading and expanding engineering. recreation vehicle campground area, day-use picnic area and swim beach development; group camp area development; pedestrian and handicapped access trails; ranger residence; maintenance building; restrooms and shelters; roads; water, sanitary, and electrical . -

Coe Portland District (Nwp) Hydropower Projects

Updated March 30, 2021. Use the appropriate district distribution list below when submitting a System Operational Request (SOR). COE PORTLAND DISTRICT (NWP) HYDROPOWER PROJECTS COE SEATTLE DISTRICT (NWS) HYDROPOWER PROJECTS Bonneville Dam & Lake on Columbia River Libby Dam & Lake Koocanusa on Kootenai River The Dalles Dam & Lake Celilo on Columbia River Hungry Horse Dam & Lake on South Fork Flathead River John Day Dam & Lake Umatilla on Columbia River Albeni Falls Dam & Pend Oreille Lake on Pend Oreille River Chief Joseph Dam and Rufus Woods Lake on Columbia River Corps of Engineers Northwestern Division (NWD) Corps of Engineers Northwestern Division (NWD) SEATTLE DISTRICT (NWS) PORTLAND DISTRICT (NWP) TO: TO: BG Pete Helmlinger COE-NWD-ZA Commander BG Pete Helmlinger COE-NWD-ZA Commander COL Alexander Bullock COE-NWS Commander COL Mike Helton COE-NWP Commander Jim Fredericks COE-NWD-PDD Chief Jim Fredericks COE-NWD-PDD Chief Steven Barton COE-NWD-PDW Chief Steven Barton COE-NWD-PDW Chief Tim Dykstra COE-NWD-PDD Tim Dykstra COE-NWD-PDD Julie Ammann COE-NWD-PDW-R Julie Ammann COE-NWD-PDW-R Doug Baus COE-NWD-PDW-R Doug Baus COE-NWD-PDW-R Aaron Marshall COE-NWD-PDW-R Aaron Marshall COE-NWD-PDW-R Lisa Wright COE-NWD-PDW-R Lisa Wright COE-NWD-PDW-R Jon Moen COE-NWS-ENH-W Tammy Mackey COE-NWP-OD Mary Karen Scullion COE-NWP-EC-HR Lorri Gray USBR-PN Regional Director Lorri Gray USBR-PN Regional Director John Roache USBR-PN-6208 John Roache USBR-PN-6208 Joel Fenolio USBR-PN-6204 Joel Fenolio USBR-PN-6204 John Hairston BPA Administrator Kieran Connolly BPA-PG-5 John Hairston BPA Administrator Scott Armentrout BPA-E-4 Kieran Connolly BPA-PG-5 Jason Sweet BPA-PGB-5 Scott Armentrout BPA-E-4 Eve James BPA-PGPO-5 Jason Sweet BPA-PGB-5 Tony Norris BPA-PGPO-5 Eve James BPA-PGPO-5 Scott Bettin BPA-EWP-4 Tony Norris BPA-PGPO-5 Tribal Liaisons: Jr. -

2018 Integrated Resource Plan

DRAFT 2018 Integrated Resource Plan Public Utility District No. 1 of Benton County PREPARED IN COLLABORATION WITH Resolution No. XXXX Contents Chapter 1: Executive Summary ..................................................................................................................... 1 Obligations and Resources ........................................................................................................................ 1 Preferred Portfolio .................................................................................................................................... 4 Chapter 2: Load Forecast .............................................................................................................................. 6 Chapter 3: Current Resources ....................................................................................................................... 7 Overview of Existing Long-term Purchased Power Agreements ............................................................... 7 Frederickson 1 Generating Station ........................................................................................................ 7 Nine Canyon Wind ................................................................................................................................. 7 White Creek Wind Generation Project .................................................................................................. 8 Packwood Lake Hydro Project .............................................................................................................. -

May 12, 2021 – 5:30 PM Douglas County Public Services Building Hearing Room 140 19Th Street NW, East Wenatchee, WA

AGENDA Wednesday – May 12, 2021 – 5:30 PM Douglas County Public Services Building Hearing Room 140 19th Street NW, East Wenatchee, WA NOTICE, in consideration of the current COVID-19 pandemic the meeting is closed to in person attendance. The meeting will be held via Zoom teleconference, attend by phone at 1-253-215-8782, Meeting ID: 937 9170 7816, Password: 520623 or online at: https://zoom.us/j/93791707816?pwd=c25FOGo4QlpUZ3BzME0xek1TMy9hQT09 I. CALL MEETING TO ORDER – Roll Call of Planning Commissioners II. ADMINISTRATIVE PROCEDURES a) Review minutes of the April 14, 2021 Planning Commission meeting. III. CITIZEN COMMENT The planning commission will allocate 15 minutes for citizen comments regarding items not related to the current agenda. IV. OLD BUSINESS - NONE V. NEW BUSINESS a) A joint Douglas County, WA Department of Ecology public hearing on limited amendments to Douglas County Shoreline Master Program. The proposed amendments are the result of the periodic review process required by RCW Chapter 90.58.080(4). b) A public hearing to consider adopting City of East Wenatchee Ordinances 2021-05, 2021-06 and 2021-08 regarding amendments to the Greater East Wenatchee Area Comprehensive Plan and Municipal Code as they apply to the unincorporated portions of the City’s urban growth area. VI. Adjourn Planning Commission meeting materials available at: http://www.douglascountywa.net/311/Planning-Commission DOUGLAS COUNTY TRANSPORTATION & LAND SERVICES 140 19TH STREET NW, SUITE A • EAST WENATCHEE, WA 98802 PHONE: 509/884-7173 • FAX: 509/886-3954 www.douglascountywa.net Douglas County Planning Commission ACTION MINUTES Wednesday, April 14, 2021 Meeting held via Zoom online meeting platform I. -

Dams and Hydroelectricity in the Columbia

COLUMBIA RIVER BASIN: DAMS AND HYDROELECTRICITY The power of falling water can be converted to hydroelectricity A Powerful River Major mountain ranges and large volumes of river flows into the Pacific—make the Columbia precipitation are the foundation for the Columbia one of the most powerful rivers in North America. River Basin. The large volumes of annual runoff, The entire Columbia River on both sides of combined with changes in elevation—from the the border is one of the most hydroelectrically river’s headwaters at Canal Flats in BC’s Rocky developed river systems in the world, with more Mountain Trench, to Astoria, Oregon, where the than 470 dams on the main stem and tributaries. Two Countries: One River Changing Water Levels Most dams on the Columbia River system were built between Deciding how to release and store water in the Canadian the 1940s and 1980s. They are part of a coordinated water Columbia River system is a complex process. Decision-makers management system guided by the 1964 Columbia River Treaty must balance obligations under the CRT (flood control and (CRT) between Canada and the United States. The CRT: power generation) with regional and provincial concerns such as ecosystems, recreation and cultural values. 1. coordinates flood control 2. optimizes hydroelectricity generation on both sides of the STORING AND RELEASING WATER border. The ability to store water in reservoirs behind dams means water can be released when it’s needed for fisheries, flood control, hydroelectricity, irrigation, recreation and transportation. Managing the River Releasing water to meet these needs influences water levels throughout the year and explains why water levels The Columbia River system includes creeks, glaciers, lakes, change frequently. -

Chapter 22 Mid-Columbia Recovery Unit—Mainstem Upper Columbia River Critical Habitat Unit

Bull Trout Final Critical Habitat Justification: Rationale for Why Habitat is Essential, and Documentation of Occupancy Chapter 22 Mid-Columbia Recovery Unit—Mainstem Upper Columbia River Critical Habitat Unit 575 Bull Trout Final Critical Habitat Justification Chapter 22 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service September 2010 Chapter 22. Mainstem Upper Columbia River Critical Habitat Unit The Mainstem Upper Columbia River CHU is essential for maintaining bull trout distribution within this unique geographic region of the Mid-Columbia RU and conserving the fluvial migratory life history types exhibited by many of the populations from adjacent core areas. It is essential for conservation by maintaining broad distribution within the Mid-Columbia RU across Washington, Idaho, and Oregon. Its location between Chief Joseph Dam in the most northern geographical area and John Day Dam in the most southern area provides key connectivity for the Mid-Columbia River RU. It is essential for maintaining distribution and genetic contributions to the Lower Columbia and Snake River Mainstems and 13 CHUs. Bull trout are known to reside year-round as sub-adults and adults, but spawning adults may utilize the mainstem Columbia River for up to at least 9 months as well. Several studies in the upper Columbia and lower Snake Rivers indicate migration between the Mainstem Upper Columbia River CHU and core areas, generally during periods of cooler water temperatures. FMO habitat provided by the mainstem Columbia River is essential for conservation because it supports the expression of the fluvial migratory life history forms for multiple core areas. In addition, there are several accounts of amphidromous life history forms present between Yakima and John Day Rivers that may still have the potential to express anadromy (see Appendix 1 for more detailed information). -

Coe Portland District (Nwp) Hydropower Projects

To submit a System Operational Request (SORs), please use the distribution list below for the relevant hydropower project. Updated September 3, 2019. COE PORTLAND DISTRICT (NWP) HYDROPOWER PROJECTS COE SEATTLE DISTRICT (NWS) HYDROPOWER PROJECTS Bonneville Dam & Lake on Columbia River Libby Dam & Lake Koocanusa on Kootenai River The Dalles Dam & Lake Celilo on Columbia River Hungry Horse Dam & Lake on South Fork Flathead River John Day Dam & Lake Umatilla on Columbia River Albeni Falls Dam & Pend Oreille Lake on Pend Oreille River Chief Joseph Dam and Rufus Woods Lake on Columbia River Corps of Engineers Northwestern Division (NWD) PORTLAND DISTRICT (NWP) Corps of Engineers Northwestern Division (NWD) TO: SEATTLE DISTRICT (NWS) BG Pete Helmlinger COE-NWD-ZA Commander TO: COL Aaron Dorf COE-NWP Commander BG Pete Helmlinger COE-NWD-ZA Commander Jim Fredericks COE-NWD-PDD Chief COL Mark Geraldi COE-NWS Commander Steven Barton COE-NWD-PDW Chief Jim Fredericks COE-NWD-PDD Chief Tim Dykstra COE-NWD-PDD Steven Barton COE-NWD-PDW Chief Julie Ammann COE-NWD-PDW-R Tim Dykstra COE-NWD-PDD Doug Baus COE-NWD-PDW-R Julie Ammann COE-NWD-PDW-R Aaron Marshall COE-NWD-PDW-R Doug Baus COE-NWD-PDW-R Tammy Mackey COE-NWP-OD Aaron Marshall COE-NWD-PDW-R Mary Karen Scullion COE-NWP-EC-HR Logan Osgood-Zimmerman COE-NWS-ENH-W Lorri Gray USBR-PN Regional Director Lorri Gray USBR-PN Regional Director John Roache USBR-PN-6208 John Roache USBR-PN-6208 Joel Fenolio USBR-PN-6204 Joel Fenolio USBR-PN-6204 Elliot Mainzer BPA Administrator Elliot Mainzer BPA Administrator Kieran Connolly BPA-PG-5 Kieran Connolly BPA-PG-5 Scott Armentrout BPA-E-4 Scott Armentrout BPA-E-4 Jason Sweet BPA-PGB-5 Jason Sweet BPA-PGB-5 Eve James BPA-PGPO-5 Eve James BPA-PGPO-5 Tony Norris BPA-PGPO-5 Tony Norris BPA-PGPO-5 Scott Bettin BPA-EWP-4 Scott Bettin BPA-EWP-4 Tribal Liaisons: Paul Cloutier (NWD), Jr. -

Idaho Falls Power

INTRODUCTION The first public utility in America began over Although Idaho Falls was not the first community to own and 120 years ago. The efforts of the early electrical operate its municipal utility, it is one of the oldest public power pioneers have allowed the nation’s municipal utilities communities in the Northwest. The city of Idaho Falls is to give inexpensive, reliable electric power to millions celebrating the past 100 years of providing its residents of Americans in the twentieth century. Today municipal ownership in its electric power system. This report municipal utilities give over 2,000 communities a will provide some interesting facts about the pioneers who sense of energy independence and autonomy they can installed a tiny electric generator on an irrigation canal in the carry into the twenty-first century. fall of 1900, establishing the beginning of the Idaho Falls municipal utility. Lucille Keefer pictured in front of the falls, is one of the more endearing images of Idaho Falls’ hydroelectric history. The Pennsylvania-born school teacher was the wife of the project’s construction superintendent. THE CANAL ERA The original 1900 power plant generated electricity from the water tumbling out of an irrigation ditch. When the Utah and Northern Railroad extended its tracks During the 1880s and 1890s, lumberyards, flourmills, to the rapids on the Snake River in 1879, the small town livestock auction houses, newspapers, banks, and clothing of Eagle Rock (now Idaho Falls) was established. The stores sprouted up along the railroad tracks. Population turn of the century not only brought more people to the surged as merchants and professionals flocked to the city to newly formed community but new developments as well. -

NMFS National Marine Fisheries Service

20120307-5193 FERC PDF (Unofficial) 3/7/2012 4:54:15 PM 20120307-5193 FERC PDF (Unofficial) 3/7/2012 4:54:15 PM 20120307-5193 FERC PDF (Unofficial) 3/7/2012 4:54:15 PM 20120307-5193 FERC PDF (Unofficial) 3/7/2012 4:54:15 PM 20120307-5193 FERC PDF (Unofficial) 3/7/2012 4:54:15 PM Table of Contents LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................................................... 4 LIST OF TABLES ........................................................................................................................ 5 TERMS AND ABBREVIATIONS .............................................................................................. 6 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................... 11 1.1 BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................................................ 11 1.2 CONSULTATION HISTORY .................................................................................................................................. 11 1.3 PROPOSED ACTION .......................................................................................................................................... 11 1.4 ACTION AREA ................................................................................................................................................. 12 2. ENDANGERED SPECIES ACT: BIOLOGICAL OPINION AND INCIDENTAL TAKE STATEMENT ................................................................................................................ -

Wells Hydroelectric Project Total Dissolved Gas Abatement Plan 2013 Annual Report

Wells Hydroelectric Project Total Dissolved Gas Abatement Plan 2013 Annual Report Public Utility District No. 1 of Douglas County 1151 Valley Mall Parkway East Wenatchee, WA 98802-4331 Prepared for: Pat Irle Hydropower Projects Manager Washington Department of Ecology 15 W. Yakima Avenue, Suite 200 Yakima, WA 98902-3452 January 2013 This page intentionally left blank TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Project Description ........................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Fixed Monitoring Site Locations .................................................................................................... 1 1.3 Regulatory Framework .................................................................................................................. 2 1.4 2013 Gas Abatement Plan Approach ............................................................................................ 3 1.4.1 Operational ........................................................................................................................... 3 1.4.2 Structural ............................................................................................................................... 3 1.4.3 Consultation .......................................................................................................................... 4 2 OPERATIONS ........................................................................................................... -

Downloaded from the DRS Website At

Quincy Chute Hydroelectric Project Wanapum Dam Seattle Spokane Grant County Potholes Priest Rapids East Canal Dam Headworks Nine Canyon Wind Farm WANAPUM DAM QUINCY CHUTE HYDROELECTRIC PROJECT Generation Units . 10. Rated Capacity . 1,203.6. MW Rated Capacity . 9.4. MW Concrete/Earthfill Length . 8,637. FT First Power Generation . .1985 Rated Head . 80 FT Construction Started . .1959 First Power Generation . .1963 POTHOLES EAST CANAL HEADWORKS PROJECT PRIEST RAPIDS DAM Rated Capacity . 6.5. MW First Power Generation . .1990 Generation Units . 10. Rated Capacity . 950. MW Concrete/Earthfill Length . 10,103. FT NINE CANYON WIND PROJECT Rated Head . 78 FT Construction Started . .1956 12 .5% of Project Peak Capacity . .12 MW First Power Generation . .1959 First Power Generation . .2003 ELECTRIC SYSTEM Overhead Distribution Lines . 2,795 MILES Underground Distribution Lines . 1,102. MILES Overhead Transformers . .24,477 Padmount Transformers . 9,935 115kV Transmission Lines . 282. MILES 230kV Transmission Lines . 202. MILES ACTIVE METERS Residential . 39,103. Irrigation . 5,193 Industrial . 122 Commercial . 7,248 Large Commercial . 107 Street Light and Other . .439 Total Active Meters . 52,212. SUBSTATIONS Distribution . 49 Transmission . 5. Transmission/Distribution . 3. HIGH SPEED NETWORK Customers with fiber-optic availability . .33,149 Customers using fiber-optic service . 19,043 Customers using wireless service . 290 As of Dec. 31, 2019 Grant PUD was established by local residents in 1938 to provide power service to all of the county’s residents. We honor the resolve of our founders through our guiding vision, mission and values. VISION Excellence in service and leadership. We continually ask how we can improve service quality, reliability and stewardship of our resources in the most cost-effective manner . -

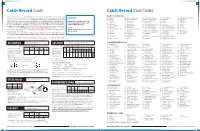

Catch Record Cards & Codes

Catch Record Cards Catch Record Card Codes The Catch Record Card is an important management tool for estimating the recreational catch of PUGET SOUND REGION sturgeon, steelhead, salmon, halibut, and Puget Sound Dungeness crab. A catch record card must be REMINDER! 824 Baker River 724 Dakota Creek (Whatcom Co.) 770 McAllister Creek (Thurston Co.) 814 Salt Creek (Clallam Co.) 874 Stillaguamish River, South Fork in your possession to fish for these species. Washington Administrative Code (WAC 220-56-175, WAC 825 Baker Lake 726 Deep Creek (Clallam Co.) 778 Minter Creek (Pierce/Kitsap Co.) 816 Samish River 832 Suiattle River 220-69-236) requires all kept sturgeon, steelhead, salmon, halibut, and Puget Sound Dungeness Return your Catch Record Cards 784 Berry Creek 728 Deschutes River 782 Morse Creek (Clallam Co.) 828 Sauk River 854 Sultan River crab to be recorded on your Catch Record Card, and requires all anglers to return their fish Catch by the date printed on the card 812 Big Quilcene River 732 Dewatto River 786 Nisqually River 818 Sekiu River 878 Tahuya River Record Card by April 30, or for Dungeness crab by the date indicated on the card, even if nothing “With or Without Catch” 748 Big Soos Creek 734 Dosewallips River 794 Nooksack River (below North Fork) 830 Skagit River 856 Tokul Creek is caught or you did not fish. Please use the instruction sheet issued with your card. Please return 708 Burley Creek (Kitsap Co.) 736 Duckabush River 790 Nooksack River, North Fork 834 Skokomish River (Mason Co.) 858 Tolt River Catch Record Cards to: WDFW CRC Unit, PO Box 43142, Olympia WA 98504-3142.