MA Thesis Gordon 05.19.10 Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trees, Knots, and Outriggers

Trees, Knots, and Outriggers Studies in Environmental Anthropology and Ethnobiology General Editor: Roy Ellen, FBA Professor of Anthropology, University of Kent at Canterbury Interest in environmental anthropology has grown steadily in recent years, refl ecting na- tional and international concern about the environment and developing research priorities. This major new international series, which continues a series fi rst published by Harwood and Routledge, is a vehicle for publishing up-to-date monographs and edited works on particular issues, themes, places or peoples which focus on the interrelationship between society, culture and environment. Relevant areas include human ecology, the perception and representation of the environment, ethno-ecological knowledge, the human dimension of biodiversity conservation and the ethnography of environmental problems. While the un- derlying ethos of the series will be anthropological, the approach is interdisciplinary. Volume 1 Volume 12 The Logic of Environmentalism: Anthropology, Unveiling the Whale: Discourses on Whales Ecology and Postcoloniality and Whaling Vassos Argyrou Arne Kalland Volume 2 Volume 13 Conversations on the Beach: Fishermen’s Virtualism, Governance and Practice: Vision and Knowledge, Metaphor and Environmental Change Execution in Environmental Conservation in South India Edited by James G. Carrier and Paige West Götz Hoeppe Volume 14 Volume 3 Ethnobotany in the New Europe: People, Health Green Encounters: Shaping and Contesting and Wild Plant Resources Environmentalism in Rural Costa Rica Edited by Manuel Pardo-de-Santayana, Andrea Luis A. Vivanco Pieroni and Rajindra K. Puri Volume 4 Volume 15 Local Science vs. Global Science: Approaches Urban Pollution: Cultural Meanings, Social to Indigenous Knowledge in International Practices Development Edited by Eveline Dürr and Rivke Jaffe Edited by Paul Sillitoe Volume 16 Volume 5 Weathering the World: Recovery in the Wake of the Sustainability and Communities of Place Tsunami in a Tamil Fishing Village Edited by Carl A. -

Pacific News from Manoa

UNIVERSITY Of HAWAII LIBRARY .. ~· ... .. Pacific News from Manoa NEWSLETTER OF THE CENTER FOR PACIAC ISLANDS STUDIES, UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I Australia and Indonesia; Ethnobotany; Geography of NOVEMBER 2002 CPIS Hawai'i; Hawai'i: Center of the Pacific; Maritime CONFERENCE TO LOOK AT l\1YTH, Archaeology Survey Techniques, and Samoan and TERRORISM, AND JUSTICE Hawaiian language courses. This year's annual conference at the Center for In addition to credit and noncredit courses, Pacific Islands Studies focuses on "Myth, Justice, and Outreach College puts on a number of public Terrorism" in film and literature from the Pacific programs. Included among these this summer is a and Asia. The conference will be held 5-8 November sneak preview of selected scenes from Fire in the 2002 in Honolulu in cooperation with the Hawai 'i Womb, a new movie by CPIS faculty member Vilsoni International Film Festival, the UH Department of HERENIKO and Jeannette Paulson HERENIKO. The English's Fall Festival of Writing, and NETPAC screenings, which are free of charge, are at 7:00 pm (Network for the Promotion of Asia/Pacific Film). In on 6 and 7 June in the Yukiyoshi Room (Krauss 12). addition to films from the Pacific and Asia, including For information on UH summer session activities, several Hawai 'i premieres, the conference will feature see the website at http://www.summer.hawaii.edu or interviews with filmmakers and panels that explore request a catalog by calling 808-956-5666. themes of terrorism and justice in film and literature. Vilsoni HERENIKO and Ruth HSU are the conference CPIS WELCOMES NEW AFFILIATE convenors. -

Paleoethnobotany of Kilgii Gwaay: a 10,700 Year Old Ancestral Haida Archaeological Wet Site

Paleoethnobotany of Kilgii Gwaay: a 10,700 year old Ancestral Haida Archaeological Wet Site by Jenny Micheal Cohen B.A., University of Victoria, 2010 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Anthropology Jenny Micheal Cohen, 2014 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. Supervisory Committee Paleoethnobotany of Kilgii Gwaay: A 10,700 year old Ancestral Haida Archaeological Wet Site by Jenny Micheal Cohen B.A., University of Victoria, 2010 Supervisory Committee Dr. Quentin Mackie, Supervisor (Department of Anthropology) Dr. Brian David Thom, Departmental Member (Department of Anthropology) Dr. Nancy Jean Turner, Outside Member (School of Environmental Studies) ii Abstract Supervisory Committee Dr. Quentin Mackie, Supervisor (Department of Anthropology) Dr. Brian David Thom, Departmental Member (Department of Anthropology) Dr. Nancy Jean Turner, Outside Member (School of Environmental Studies) This thesis is a case study using paleoethnobotanical analysis of Kilgii Gwaay, a 10,700- year-old wet site in southern Haida Gwaii to explore the use of plants by ancestral Haida. The research investigated questions of early Holocene wood artifact technologies and other plant use before the large-scale arrival of western redcedar (Thuja plicata), a cultural keystone species for Haida in more recent times. The project relied on small- scale excavations and sampling from two main areas of the site: a hearth complex and an activity area at the edge of a paleopond. The archaeobotanical assemblage from these two areas yielded 23 plant taxa representing 14 families in the form of wood, charcoal, seeds, and additional plant macrofossils. -

Eugene S. Hunn Bibliography Anthropology Books and Museum

1 Eugene S. Hunn Bibliography Anthropology Books and Museum Catalogs Hunn, Eugene S. 1977. Tzeltal Folk Zoology: The Classification of Discontinuities in Nature. Academic Press, New York. Hunn, Eugene, with Constance Baltuck. 1981. A Photocopy Collection of Native Plants of Washington, 1981. Seattle: Thomas Burke Memorial Washington State Museum. Hunn, Eugene S. 1982. Birding in Seattle and King County. Seattle Audubon Society, Seattle, Washington. Williams, Nancy M., and Eugene S. Hunn, eds. 1982. Resource Managers: North American and Australian Hunter-Gatherers. American Association for the Advancement of Science Selected Symposia Series. Westview Press. Boulder, Colorado. Paperback edition published by the Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, Canberra, Australia, 1986. Hunn, Eugene S. 1990. Nch'i-Wana, “The Big River”: Mid-Columbia Indians and Their Land. University of Washington Press, Seattle, Washington. Paperback edition, 1991. Governor's Writers Award, 1992. Second printing, 1995. Hunn, Eugene S., Darryll R. Johnson, Priscilla N. Russell, and Thomas F. Thornton. 2004. The Huna Tlingit People’s Traditional Use of gull Eggs and the Establishment of Glacier Bay National Park. Technical Report NPS D-121. Seattle, WA: National Park Service. Hunn, Eugene S. 2008. A Zapotec Natural History: Trees, Herbs, and Flowers, Birds, Beasts, and Bugs in the Life of San Juan Gbëë, with CD Rom. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. Association of American Publishers Prose Award for excellence in Archaeology & Anthropology, 2008. Johnson, Leslie Main, and Eugene S. Hunn, eds. 2010. Landscape Ethnoecology: Concepts of Biotic and Physical Space. Volume 14, Studies in Environmental Anthropology and Ethnobiology. New York and Oxford: Berghahn Books. E. N. Anderson, Deborah M. -

Gitksan Plant Classification and Nomenclature

Journal of Ethnobiology 19(2): 179-218 Winler 1999 GITKSAN PLANT CLASSIFICATION AND NOMENCLATURE LESLIE MAIN JOHNSON Department ofAnthropology, University ofAlberta Edmonton, Alberta, Canada T6G 2H4 ABSTRACT.- The Gitksan of northwestern British Columbia are speakers of an Interior Tsimshianic language. They live in a mountainous, densely forested environment transitional between the Northwest Coast and the Boreal interior plateau. Traditionally the Gitksan pursued a mixed fishing/hunting/ gathering subsistence strategy. The Gitksan have a roughly hierarchical classification of plants. The general domain 'plant kingdom' or 'floral form' is recognized but not overtly labelled. Within this, several broad groupings of the life form sort can be distinguished. Three of these are large groupings composed ofa number of named subordinate generics: gan 'trees,' sgan 'plants,' and maa'y 'berry' or 'fruit plants.' 'Plants' include a diverse mixture of forms ranging from small trees to some perennial herbs, and prostrate sub-shrubs. The 'plant' and the 'berry' groups overlap extensively. The remainder are residual taxa which are empty, containing few or no named subtypes, though encompassing morphological and taxonomically diverse forms: habasxw'grass' or'hay,' 'yens 'leaves' or 'herbaceous plants,' majagalee 'flowers,' umhlw 'moss,' and.gayda ts'uuts 'fungi.' A mixture of morphologic and utilitarian characters seems to underlie the system of plant classification. The relationship of partonomy to utility and classification is explored. Ninety distinct generics have been documented. Eighty-four represent vascular plants and six represent mosses, fungi and lichens. Keywords: classification, Gitksan, ethnobotany, Canada, Northwest Coast RFSUMEN.- Los Gitksan hablan una Iengua tsimsiana interior. Viven en una region montaflosa y de bosques densos. -

An Earthly Cosmology

Forum on Religion and Ecology Indigenous Traditions and Ecology Annotated Bibliography Abram, David. Becoming Animal: An Earthly Cosmology. New York and Canada: Vintage Books, 2011. As the climate veers toward catastrophe, the innumerable losses cascading through the biosphere make vividly evident the need for a metamorphosis in our relation to the living land. For too long we’ve ignored the wild intelligence of our bodies, taking our primary truths from technologies that hold the living world at a distance. Abram’s writing subverts this distance, drawing readers ever closer to their animal senses in order to explore, from within, the elemental kinship between the human body and the breathing Earth. The shape-shifting of ravens, the erotic nature of gravity, the eloquence of thunder, the pleasures of being edible: all have their place in this book. --------. The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in a More-than-Human World. New York: Vintage, 1997. Abram argues that “we are human only in contact, and conviviality, with what is not human” (p. ix). He supports this premise with empirical information, sensorial experience, philosophical reflection, and the theoretical discipline of phenomenology and draws on Merleau-Ponty’s philosophy of perception as reciprocal exchange in order to illuminate the sensuous nature of language. Additionally, he explores how Western civilization has lost this perception and provides examples of cultures in which the “landscape of language” has not been forgotten. The environmental crisis is central to Abram’s purpose and despite his critique of the consequences of a written culture, he maintains the importance of literacy and encourages the release of its true potency. -

Download Download

Ames, Kenneth M. and Herbert D.G. Maschner 1999 Peoples of BIBLIOGRAPHY the Northwest Coast: Their Archaeology and Prehistory. Thames and Hudson, London. Abbas, Rizwaan 2014 Monitoring of Bell-hole Tests at Amoss, Pamela T. 1993 Hair of the Dog: Unravelling Pre-contact Archaeological Site DhRs-1 (Marpole Midden), Vancouver, BC. Coast Salish Social Stratification. In American Indian Linguistics Report on file, British Columbia Archaeology Branch, Victoria. and Ethnography in Honor of Lawrence C. Thompson, edited by Acheson, Steven 2009 Marpole Archaeological Site (DhRs-1) Anthony Mattina and Timothy Montler, pp. 3-35. University of Management Plan—A Proposal. Report on file, British Columbia Montana Occasional Papers No. 10, Missoula. Archaeology Branch, Victoria. Andrefsky, William, Jr. 2005 Lithics: Macroscopic Approaches to Acheson, S. and S. Riley 1976 Gulf of Georgia Archaeological Analysis (2nd edition). Cambridge University Press, New York. Survey: Powell River and Sechelt Regional Districts. Report on Angelbeck, Bill 2015 Survey and Excavation of Kwoiek Creek, file, British Columbia Archaeology Branch, Victoria. British Columbia. Report in preparation by Arrowstone Acheson, S. and S. Riley 1977 An Archaeological Resource Archaeology for Kanaka Bar Indian Band, and Innergex Inventory of the Northeast Gulf of Georgia Region. Report on file, Renewable Energy, Longueuil, Québec. British Columbia Archaeology Branch, Victoria. Angelbeck, Bill and Colin Grier 2012 Anarchism and the Adachi, Ken 1976 The Enemy That Never Was. McClelland & Archaeology of Anarchic Societies: Resistance to Centralization in Stewart, Toronto, Ontario. the Coast Salish Region of the Pacific Northwest Coast. Current Anthropology 53(5):547-587. Adams, Amanda 2003 Visions Cast on Stone: A Stylistic Analysis of the Petroglyphs of Gabriola Island, B.C. -

Archaeologists and Indigenous Traditional Knowledge in British Columbia

Archaeologists and Indigenous Traditional Knowledge in British Columbia by Eric Simons B.A. (Archaeology) Simon Fraser University, 2014 B.F.A. (Visual Arts) Simon Fraser University, 2006 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Archaeology Faculty of Environment © Eric Simons SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2017 Copyright in this work rests with the author. Please ensure that any reproduction or re-use is done in accordance with the relevant national copyright legislation. Approval Name: Eric Simons Degree: Master of Arts Title: Archaeologists and Indigenous Traditional Knowledge in British Columbia Examining Committee: Chair: Catherine D’Andrea Professor George Nicholas Senior Supervisor Professor Dana Lepofsky Supervisor Professor Annie Ross External Examiner Honorary Associate Professor School of Social Science The University of Queensland, Australia Date Defended/Approved: July 21, 2017 ii Ethics Statement iii Abstract Archaeologists who study the past histories and lifeways of Indigenous cultures have long used Indigenous traditional knowledge as a source of historical information. Initially, archaeologists primarily accessed traditional knowledge second-hand, attempting to extract historical data from ethnographic sources. However, as archaeologists increasingly work with (and sometimes for) Indigenous communities, they have the opportunity to access traditional knowledge directly. Traditional knowledge is a powerful resource for archaeology, but working with it raises significant socio-political issues. Additionally, integrating traditional knowledge with archaeology’s interpretive frameworks can present methodological and epistemological challenges. This thesis examines the implications of archaeologists’ engagement with traditional knowledge in British Columbia, Canada, where changes at both a disciplinary and broader societal level indicate that archaeologists will increasingly need to find effective and ethical ways to work with traditional knowledge (and knowledge-holders). -

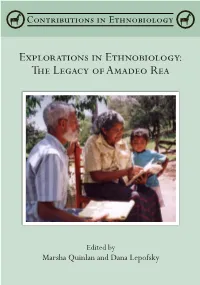

Explorations in Ethnobiology: the Legacy of Amadeo Rea

Explorations in Ethnobiology: The Legacy of Amadeo Rea Edited by Marsha Quinlan and Dana Lepofsky Explorations in Ethnobiology: The Legacy of Amadeo Rea Edited by Marsha Quinlan and Dana Lepofsky Copyright 2013 ISBN-10: 0988733013 ISBN-13: 978-0-9887330-1-5 Library of Congress Control Number: 2012956081 Society of Ethnobiology Department of Geography University of North Texas 1155 Union Circle #305279 Denton, TX 76203-5017 Cover photo: Amadeo Rea discussing bird taxonomy with Mountain Pima Griselda Coronado Galaviz of El Encinal, Sonora, Mexico, July 2001. Photograph by Dr. Robert L. Nagell, used with permission. Contents Preface to Explorations in Ethnobiology: The Legacy of Amadeo Rea . i Dana Lepofsky and Marsha Quinlan 1 . Diversity and its Destruction: Comments on the Chapters . .1 Amadeo M. Rea 2 . Amadeo M . Rea and Ethnobiology in Arizona: Biography of Influences and Early Contributions of a Pioneering Ethnobiologist . .11 R. Roy Johnson and Kenneth J. Kingsley 3 . Ten Principles of Ethnobiology: An Interview with Amadeo Rea . .44 Dana Lepofsky and Kevin Feeney 4 . What Shapes Cognition? Traditional Sciences and Modern International Science . .60 E.N. Anderson 5 . Pre-Columbian Agaves: Living Plants Linking an Ancient Past in Arizona . .101 Wendy C. Hodgson 6 . The Paleobiolinguistics of Domesticated Squash (Cucurbita spp .) . .132 Cecil H. Brown, Eike Luedeling, Søren Wichmann, and Patience Epps 7 . The Wild, the Domesticated, and the Coyote-Tainted: The Trickster and the Tricked in Hunter-Gatherer versus Farmer Folklore . .162 Gary Paul Nabhan 8 . “Dog” as Life-Form . .178 Eugene S. Hunn 9 . The Kasaga’yu: An Ethno-Ornithology of the Cattail-Eater Northern Paiute People of Western Nevada . -

Pdf/ Pubjood the Primary Application of Anthocyanoside-Enriched Bilberry Food.-Contentslot- 5180- Itemlist- 23399- File

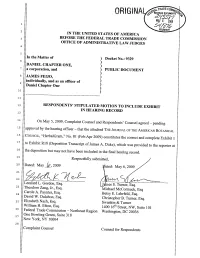

ORIGINA 1 2 IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA 3 BEFORE THE FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION OFFICE OF ADMINISTRATIVE LAW JUDGES 4 5 In the Matter of ) Docket No.: 9329 6 DANIEL CHAPTER ONE, ) ) 7 a corporation, and ) PUBLIC DOCUMENT ) 8 JAMES FEIJO, ) individually, and as an offcer of ) 9 Daniel Chapter One ) 10 ) ) 11 12 RESPONDENTS' STIPULATED MOTION TO INCLUDE EXHIBIT IN HEARING RECORD 13 14 On May 5, 2009, Complaint Counsel and Respondents' Counsel agreed - pending 15 approval by the hearing officer - that the attached THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN BOTANICAL 16 COUNCIL, "HerbaIGram," No. 81 (Feb-Apr 2009) constitutes the correct and complete Exhibit 1 17 to Exhibit R18 (Deposition Transcript of James A. Duke), which was provided to the reporter at 18 the deposition but may not have been included in the final hearing record. 19 Respectfully submitted, 20 Dated: May~, 2009 21 22 ~;: 71 lJ Leonard L. Gordon, Esq. J mes S. Turner, Esq. 23 Theodore Zang, Jr., Esq. Michael McCormack, Esq Carole A. Paynter, Esq. 24 Betsy E. Lehrfeld, Esq. David W. Dulabon, Esq. Chrstopher B. Turner, Esq. 25 Elizabeth N ach, Esq. Swankin & Turner Wiliam H. Efron, Esq. 1400 16th Street, NW, Suite 101 26 Federal Trade Commission - Northeast Region Washington, DC 20036 27 One Bowling Green, Suite 318 New York, NY 10004 28 Complaint Counsel Counsel for Respondents 1 2 (PROPOSED) ORDER 3 The parties having agreed that Exhibit 1 to Exhibit R18 consists of THE JOURNAL OF THE 4 AMERICAN BOTANICAL COUNCIL, "HerbaIGram," No. 81 (Feb-Apr 2009), 5 6 IT is ORDERED that 7 To the extent it is necessary to change the hearing record such that Exhibit 1 to Exhibit 8 R18 shall consist of THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN BOTANICAL COUNCIL, "HerbaIGram," No. -

Careers in Ethnobotany

New Ethnoecology Position at University of Hawaii Notice sent in by Will McClatchey Dear SEB members, We are happy to announce that the University of Hawaii at Manoa is seeking to hire a new faculty member with expertise in the area of ethnoecology. The position is part of a larger effort to integrate the teaching and research activities of several departments into an ethnobiology program with certificates and degrees in ethnobotany, ethnobiology, ethnoecology, and ethnopharmacology. Current ethnobiology faculty include: Al Chock, Nina Etkin, Will McClatchey, Mark Merlin, and Lyndon Wester. Tentative closing date is September 15th, 2000. ETHNOECOLOGIST: The Department of Botany, College of Natural Sciences, invites applicants for an Assistant Professor, full-time, tenure track, nine-month position to begin January 3, 2001, pending position clearance and availability of funds. The department seeks an individual who will develop an outstanding research program and provide leadership in ethnoecology and related fields that emphasize studies of cultural interactions with botanical environments. Primary teaching responsibilities will include an introductory course in the undergraduate Ethnobiology curriculum, a lower division course in Botany or Biology, and an advanced course in the area of his/her research specialization. Secondarily, the individual will be expected to interact with the Ecology, Evolution, and Conservation Biology program through teaching and/or research activities. Minimum qualifications are a Ph.D. in botany, an appropriate field of biological science or its equivalent; demonstrated teaching ability; demonstrated scholarly achievements. Desirable qualifications include postgraduate training and field-oriented research in Pacific or tropical ethnoecology, the ability to operate in a multi-cultural environment, and significant knowledge of, or interest in, traditional land use systems of the Pacific. -

SES 15/40 the School of Environmental Studies 15 Years 1999-‐2014 the Environmental Studies Program 40 Years 1974-‐2014

SES 15/40 The School of Environmental Studies 15 Years 1999-‐2014 The Environmental Studies Program 40 Years 1974-‐2014 1 Table of Contents History of the School ................................ ................................................................................................ 5 SES 15 Milestones ................................ ...................................................................................................... 6 1. The school's three pillars................................ .............................................................................. 6 2. Restoration of Natural Systems Program and Native Species and Natural Processes Certificate ................................ ............................................................................................ 7 3. Redfish School of Change ................................ .............................................................................. 8 4. Hakai Chair in Ethnoecology ................................ ....................................................................... 9 5. Restoration Institute ................................ .................................................................................... 10 6. Seafood Ecology Research Group................................ ........................................................... 11 7. Mountain Legacy ................................ Project ............................................................................ 12 8. Master’s and Doctoral Programs...............................