Archaeologists and Indigenous Traditional Knowledge in British Columbia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issue Information

Juengst and Becker, Editors Editors and Becker, Juengst of Community The Bioarchaeology 28 AP3A No. The Bioarchaeology of Community Sara L. Juengst and Sara K. Becker, Editors Contributions by Sara K. Becker Deborah Blom Jered B. Cornelison Sylvia Deskaj Lynne Goldstein Sara L. Juengst Ann M. Kakaliouras Wendy Lackey-Cornelison William J. Meyer Anna C. Novotny Molly K. Zuckerman 2017 Archeological Papers of the ISSN 1551-823X American Anthropological Association, Number 28 aapaa_28_1_cover.inddpaa_28_1_cover.indd 1 112/05/172/05/17 22:26:26 PPMM The Bioarchaeology of Community Sara L. Juengst and Sara K. Becker, Editors Contributions by Sara K. Becker Deborah Blom Jered B. Cornelison Sylvia Deskaj Lynne Goldstein Sara L. Juengst Ann M. Kakaliouras Wendy Lackey-Cornelison William J. Meyer Anna C. Novotny Molly K. Zuckerman 2017 Archeological Papers of the American Anthropological Association, Number 28 ARCHEOLOGICAL PAPERS OF THE AMERICAN ANTHROPOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION Lynne Goldstein, General Series Editor Number 28 THE BIOARCHAEOLOGY OF COMMUNITY 2017 Aims and Scope: The Archaeological Papers of the American Anthropological Association (AP3A) is published on behalf of the Archaeological Division of the American Anthropological Association. AP3A publishes original monograph-length manuscripts on a wide range of subjects generally considered to fall within the purview of anthropological archaeology. There are no geographical, temporal, or topical restrictions. Organizers of AAA symposia are particularly encouraged to submit manuscripts, but submissions need not be restricted to these or other collected works. Copyright and Copying (in any format): © 2017 American Anthropological Association. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission in writing from the copyright holder. -

Paleoethnobotany of Kilgii Gwaay: a 10,700 Year Old Ancestral Haida Archaeological Wet Site

Paleoethnobotany of Kilgii Gwaay: a 10,700 year old Ancestral Haida Archaeological Wet Site by Jenny Micheal Cohen B.A., University of Victoria, 2010 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Anthropology Jenny Micheal Cohen, 2014 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. Supervisory Committee Paleoethnobotany of Kilgii Gwaay: A 10,700 year old Ancestral Haida Archaeological Wet Site by Jenny Micheal Cohen B.A., University of Victoria, 2010 Supervisory Committee Dr. Quentin Mackie, Supervisor (Department of Anthropology) Dr. Brian David Thom, Departmental Member (Department of Anthropology) Dr. Nancy Jean Turner, Outside Member (School of Environmental Studies) ii Abstract Supervisory Committee Dr. Quentin Mackie, Supervisor (Department of Anthropology) Dr. Brian David Thom, Departmental Member (Department of Anthropology) Dr. Nancy Jean Turner, Outside Member (School of Environmental Studies) This thesis is a case study using paleoethnobotanical analysis of Kilgii Gwaay, a 10,700- year-old wet site in southern Haida Gwaii to explore the use of plants by ancestral Haida. The research investigated questions of early Holocene wood artifact technologies and other plant use before the large-scale arrival of western redcedar (Thuja plicata), a cultural keystone species for Haida in more recent times. The project relied on small- scale excavations and sampling from two main areas of the site: a hearth complex and an activity area at the edge of a paleopond. The archaeobotanical assemblage from these two areas yielded 23 plant taxa representing 14 families in the form of wood, charcoal, seeds, and additional plant macrofossils. -

Courage and Thoughtful Scholarship = Indigenous Archaeology Partnerships

FORUM COURAGE AND THOUGHTFUL SCHOLARSHIP = INDIGENOUS ARCHAEOLOGY PARTNERSHIPS Dale R. eroes Robert McGhee's recent lead-in American Antiquity article entitled Aboriginalism and Problems of Indigenous archaeology seems to emphasize the pitfalls that can occur in "indige nolls archaeology." Though the effort is l1ever easy, I would empha size an approach based on a 50/50 partnership between the archaeological scientist and the native people whose past we are attempting to study through our field alld research techniques. In northwestern North America, we have found this approach important in sharillg ownership of the scientist/tribal effort, and, equally important, in adding highly significant (scientif ically) cullUral knowledge ofTribal members through their ongoing cultural transmission-a concept basic to our explana tion in the field of archaeology and anthropology. Our work with ancient basketry and other wood and fiber artifacts from waterlogged Northwest Coast sites demonstrates millennia ofcultl/ral cOlltinuity, often including reg ionally distinctive, highly guarded cultural styles or techniques that tribal members continue to use. A 50/50 partnership means, and allows, joint ownership that can only expand the scientific description and the cultural explanation through an Indigenous archaeology approach. El artIculo reciente de Robert McGhee en la revista American Antiquity, titulado: Aborigenismo y los problemas de la Arque ologia Indigenista, pC/recen enfatizar las dificultades que pueden ocurrir en la "arqueologfa indigenista -

Archaeology and Development / Peter G. Gould

Theme01: Archaeology and Development / Peter G. Gould Poster T01-91P / Mohammed El Khalili / Managing Change in an ever-Changing Archeological Landscape: Safeguard the Natural and Cultural Landscape of Jarash T01-92P / Wai Man Raymond Lee / Archaeology and Development: a Case Study under the Context of Hong Kong T01A / RY103 / SS5,SS6 T01A01 / Emmanuel Ndiema / Engaging Communities in Cultural Heritage Conservation: Perspectives from Kakapel, Western Kenya T01A02 / Paul Edward Montgomery / Branding Barbarians: The Development of Renewable Archaeotourism Destinations to Re-Present Marginalized Cultures of the Past T01A03 / Selvakumar Veerasamy / Historical Sites and Monuments and Community Development: Practical Issues and ground realities T01A04 / Yoshitaka SASAKI / Sustainable Utilization Approach to Cultural Heritage and the Benefits for Tourists and Local Communities: The Case of Akita Fortification, Akita prefecture, Japan. T01A05 / Angela Kabiru / Sustainable Development and Tourism: Issues and Challenges in Lamu old Town T01A06 / Chulani Rambukwella / ENDANGERED ARCHAEOLOGICAL LANDSCAPE OF THE WORLD HERITAGE CITY OF KANDY AND ITS SUBURBS IN SRI LANKA T01A07 / chandima bogahawatta / Sigiriya: World’s Oldest Living Heritage and Multi Tourist Attraction T01A08 / Shahnaj Husne Jahan Leena / Sustainable Development through Archaeological Heritage Management and Eco-Tourism at Bhitargarh in Bangladesh T01A09 / OLALEKAN AKINADE / IGBO UKWU ARCHAEOLOGICAL HERITAGE AS A BOOST TO NIGERIAN CULTURAL HERITAGE OLALEKAN AJAO AKINADE, [email protected] -

Gitksan Plant Classification and Nomenclature

Journal of Ethnobiology 19(2): 179-218 Winler 1999 GITKSAN PLANT CLASSIFICATION AND NOMENCLATURE LESLIE MAIN JOHNSON Department ofAnthropology, University ofAlberta Edmonton, Alberta, Canada T6G 2H4 ABSTRACT.- The Gitksan of northwestern British Columbia are speakers of an Interior Tsimshianic language. They live in a mountainous, densely forested environment transitional between the Northwest Coast and the Boreal interior plateau. Traditionally the Gitksan pursued a mixed fishing/hunting/ gathering subsistence strategy. The Gitksan have a roughly hierarchical classification of plants. The general domain 'plant kingdom' or 'floral form' is recognized but not overtly labelled. Within this, several broad groupings of the life form sort can be distinguished. Three of these are large groupings composed ofa number of named subordinate generics: gan 'trees,' sgan 'plants,' and maa'y 'berry' or 'fruit plants.' 'Plants' include a diverse mixture of forms ranging from small trees to some perennial herbs, and prostrate sub-shrubs. The 'plant' and the 'berry' groups overlap extensively. The remainder are residual taxa which are empty, containing few or no named subtypes, though encompassing morphological and taxonomically diverse forms: habasxw'grass' or'hay,' 'yens 'leaves' or 'herbaceous plants,' majagalee 'flowers,' umhlw 'moss,' and.gayda ts'uuts 'fungi.' A mixture of morphologic and utilitarian characters seems to underlie the system of plant classification. The relationship of partonomy to utility and classification is explored. Ninety distinct generics have been documented. Eighty-four represent vascular plants and six represent mosses, fungi and lichens. Keywords: classification, Gitksan, ethnobotany, Canada, Northwest Coast RFSUMEN.- Los Gitksan hablan una Iengua tsimsiana interior. Viven en una region montaflosa y de bosques densos. -

Aboriginal Rock Art and Dendroglyphs of Queensland's Wet Tropics

ResearchOnline@JCU This file is part of the following reference: Buhrich, Alice (2017) Art and identity: Aboriginal rock art and dendroglyphs of Queensland's Wet Tropics. PhD thesis, James Cook University. Access to this file is available from: https://researchonline.jcu.edu.au/51812/ The author has certified to JCU that they have made a reasonable effort to gain permission and acknowledge the owner of any third party copyright material included in this document. If you believe that this is not the case, please contact [email protected] and quote https://researchonline.jcu.edu.au/51812/ Art and Identity: Aboriginal rock art and dendroglyphs of Queensland’s Wet Tropics Alice Buhrich BA (Hons) July 2017 Submitted as part of the research requirements for Doctor of Philosophy, College of Arts, Society and Education, James Cook University Acknowledgements First, I would like to thank the many Traditional Owners who have been my teachers, field companions and friends during this thesis journey. Alf Joyce, Steve Purcell, Willie Brim, Alwyn Lyall, Brad Grogan, Billie Brim, George Skeene, Brad Go Sam, Marita Budden, Frank Royee, Corey Boaden, Ben Purcell, Janine Gertz, Harry Gertz, Betty Cashmere, Shirley Lifu, Cedric Cashmere, Jeanette Singleton, Gavin Singleton, Gudju Gudju Fourmile and Ernie Grant, it has been a pleasure working with every one of you and I look forward to our future collaborations on rock art, carved trees and beyond. Thank you for sharing your knowledge and culture with me. This thesis would never have been completed without my team of fearless academic supervisors and mentors, most importantly Dr Shelley Greer. -

An Earthly Cosmology

Forum on Religion and Ecology Indigenous Traditions and Ecology Annotated Bibliography Abram, David. Becoming Animal: An Earthly Cosmology. New York and Canada: Vintage Books, 2011. As the climate veers toward catastrophe, the innumerable losses cascading through the biosphere make vividly evident the need for a metamorphosis in our relation to the living land. For too long we’ve ignored the wild intelligence of our bodies, taking our primary truths from technologies that hold the living world at a distance. Abram’s writing subverts this distance, drawing readers ever closer to their animal senses in order to explore, from within, the elemental kinship between the human body and the breathing Earth. The shape-shifting of ravens, the erotic nature of gravity, the eloquence of thunder, the pleasures of being edible: all have their place in this book. --------. The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in a More-than-Human World. New York: Vintage, 1997. Abram argues that “we are human only in contact, and conviviality, with what is not human” (p. ix). He supports this premise with empirical information, sensorial experience, philosophical reflection, and the theoretical discipline of phenomenology and draws on Merleau-Ponty’s philosophy of perception as reciprocal exchange in order to illuminate the sensuous nature of language. Additionally, he explores how Western civilization has lost this perception and provides examples of cultures in which the “landscape of language” has not been forgotten. The environmental crisis is central to Abram’s purpose and despite his critique of the consequences of a written culture, he maintains the importance of literacy and encourages the release of its true potency. -

Indigenous Archaeology: Historical Interpretation from an Emic Perspective

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Nebraska Anthropologist Anthropology, Department of 2010 Indigenous Archaeology: Historical Interpretation from an Emic Perspective Stephanie M. Kennedy Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nebanthro Part of the Anthropology Commons Kennedy, Stephanie M., "Indigenous Archaeology: Historical Interpretation from an Emic Perspective" (2010). Nebraska Anthropologist. 55. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nebanthro/55 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Anthropology, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nebraska Anthropologist by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Indigenous Archaeology: Historical Interpretation from an Emic Perspective Stephanie M. Kennedy Abstract: This inquiry explores indigenous archaeology as a form of resistance to dominant Western science. Literature was identified and analyzed pertaining to the success of indigenous archaeology in the United States, British Columbia, and Australia. It is argued that a more inclusive archaeology is necessary, one that encourages partnerships with Indigenous groups in the interpretation oftheir own past. This study has implications for how we perceive Indigenous peoples from an archaeological perspective. Introduction Smith and Jackson remind us of the contextual nature of interpretation as well as the importance of the past: The shards of the past insinuate themselves into what we see, and don't see, value, and don't value, subtly informing every gaze, every movement, every decision. The privileges we enjoy, or don't enjoy, the inequities we fail to notice, or rail against, are the individual legacies of our shared pasts. -

Millennial Archaeology. Locating the Discipline in the Age of Insecurity

Archaeological Dialogues http://journals.cambridge.org/ARD Additional services for Archaeological Dialogues: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here Millennial archaeology. Locating the discipline in the age of insecurity Shannon Lee Dawdy Archaeological Dialogues / Volume 16 / Issue 02 / December 2009, pp 131 - 142 DOI: 10.1017/S1380203809990055, Published online: 05 November 2009 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S1380203809990055 How to cite this article: Shannon Lee Dawdy (2009). Millennial archaeology. Locating the discipline in the age of insecurity. Archaeological Dialogues, 16, pp 131-142 doi:10.1017/S1380203809990055 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/ARD, IP address: 128.148.252.35 on 24 Jan 2016 discussion article Archaeological Dialogues 16 (2) 131–142 C Cambridge University Press 2009 doi:10.1017/S1380203809990055 Millennial archaeology. Locating the discipline in the age of insecurity Shannon Lee Dawdy Abstract This discussion article responds to a forum question posed by the editors of Archaeological dialogues: ‘is archaeology useful?’ My response initially moves backward from the question, considering whether archaeology ought to be useful, how it has been useful in the past, and the millennial overtones of the question in our present climate of crisis. I critique the primary way in which archaeology attempts to be useful, as a dowsing rod for heritage through ‘public archaeology’. While European archaeology has long been aware of the dangers of nationalism, in the Americas this danger is cloaked by a focus on indigenous and minority histories. I then move forward through the question and urge colleagues to embrace an archaeological agenda geared towards the future rather than the past. -

Download Download

Ames, Kenneth M. and Herbert D.G. Maschner 1999 Peoples of BIBLIOGRAPHY the Northwest Coast: Their Archaeology and Prehistory. Thames and Hudson, London. Abbas, Rizwaan 2014 Monitoring of Bell-hole Tests at Amoss, Pamela T. 1993 Hair of the Dog: Unravelling Pre-contact Archaeological Site DhRs-1 (Marpole Midden), Vancouver, BC. Coast Salish Social Stratification. In American Indian Linguistics Report on file, British Columbia Archaeology Branch, Victoria. and Ethnography in Honor of Lawrence C. Thompson, edited by Acheson, Steven 2009 Marpole Archaeological Site (DhRs-1) Anthony Mattina and Timothy Montler, pp. 3-35. University of Management Plan—A Proposal. Report on file, British Columbia Montana Occasional Papers No. 10, Missoula. Archaeology Branch, Victoria. Andrefsky, William, Jr. 2005 Lithics: Macroscopic Approaches to Acheson, S. and S. Riley 1976 Gulf of Georgia Archaeological Analysis (2nd edition). Cambridge University Press, New York. Survey: Powell River and Sechelt Regional Districts. Report on Angelbeck, Bill 2015 Survey and Excavation of Kwoiek Creek, file, British Columbia Archaeology Branch, Victoria. British Columbia. Report in preparation by Arrowstone Acheson, S. and S. Riley 1977 An Archaeological Resource Archaeology for Kanaka Bar Indian Band, and Innergex Inventory of the Northeast Gulf of Georgia Region. Report on file, Renewable Energy, Longueuil, Québec. British Columbia Archaeology Branch, Victoria. Angelbeck, Bill and Colin Grier 2012 Anarchism and the Adachi, Ken 1976 The Enemy That Never Was. McClelland & Archaeology of Anarchic Societies: Resistance to Centralization in Stewart, Toronto, Ontario. the Coast Salish Region of the Pacific Northwest Coast. Current Anthropology 53(5):547-587. Adams, Amanda 2003 Visions Cast on Stone: A Stylistic Analysis of the Petroglyphs of Gabriola Island, B.C. -

Explorations in Ethnobiology: the Legacy of Amadeo Rea

Explorations in Ethnobiology: The Legacy of Amadeo Rea Edited by Marsha Quinlan and Dana Lepofsky Explorations in Ethnobiology: The Legacy of Amadeo Rea Edited by Marsha Quinlan and Dana Lepofsky Copyright 2013 ISBN-10: 0988733013 ISBN-13: 978-0-9887330-1-5 Library of Congress Control Number: 2012956081 Society of Ethnobiology Department of Geography University of North Texas 1155 Union Circle #305279 Denton, TX 76203-5017 Cover photo: Amadeo Rea discussing bird taxonomy with Mountain Pima Griselda Coronado Galaviz of El Encinal, Sonora, Mexico, July 2001. Photograph by Dr. Robert L. Nagell, used with permission. Contents Preface to Explorations in Ethnobiology: The Legacy of Amadeo Rea . i Dana Lepofsky and Marsha Quinlan 1 . Diversity and its Destruction: Comments on the Chapters . .1 Amadeo M. Rea 2 . Amadeo M . Rea and Ethnobiology in Arizona: Biography of Influences and Early Contributions of a Pioneering Ethnobiologist . .11 R. Roy Johnson and Kenneth J. Kingsley 3 . Ten Principles of Ethnobiology: An Interview with Amadeo Rea . .44 Dana Lepofsky and Kevin Feeney 4 . What Shapes Cognition? Traditional Sciences and Modern International Science . .60 E.N. Anderson 5 . Pre-Columbian Agaves: Living Plants Linking an Ancient Past in Arizona . .101 Wendy C. Hodgson 6 . The Paleobiolinguistics of Domesticated Squash (Cucurbita spp .) . .132 Cecil H. Brown, Eike Luedeling, Søren Wichmann, and Patience Epps 7 . The Wild, the Domesticated, and the Coyote-Tainted: The Trickster and the Tricked in Hunter-Gatherer versus Farmer Folklore . .162 Gary Paul Nabhan 8 . “Dog” as Life-Form . .178 Eugene S. Hunn 9 . The Kasaga’yu: An Ethno-Ornithology of the Cattail-Eater Northern Paiute People of Western Nevada . -

Pdf/ Pubjood the Primary Application of Anthocyanoside-Enriched Bilberry Food.-Contentslot- 5180- Itemlist- 23399- File

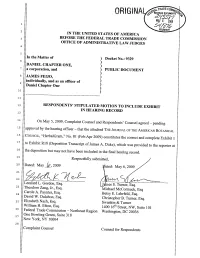

ORIGINA 1 2 IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA 3 BEFORE THE FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION OFFICE OF ADMINISTRATIVE LAW JUDGES 4 5 In the Matter of ) Docket No.: 9329 6 DANIEL CHAPTER ONE, ) ) 7 a corporation, and ) PUBLIC DOCUMENT ) 8 JAMES FEIJO, ) individually, and as an offcer of ) 9 Daniel Chapter One ) 10 ) ) 11 12 RESPONDENTS' STIPULATED MOTION TO INCLUDE EXHIBIT IN HEARING RECORD 13 14 On May 5, 2009, Complaint Counsel and Respondents' Counsel agreed - pending 15 approval by the hearing officer - that the attached THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN BOTANICAL 16 COUNCIL, "HerbaIGram," No. 81 (Feb-Apr 2009) constitutes the correct and complete Exhibit 1 17 to Exhibit R18 (Deposition Transcript of James A. Duke), which was provided to the reporter at 18 the deposition but may not have been included in the final hearing record. 19 Respectfully submitted, 20 Dated: May~, 2009 21 22 ~;: 71 lJ Leonard L. Gordon, Esq. J mes S. Turner, Esq. 23 Theodore Zang, Jr., Esq. Michael McCormack, Esq Carole A. Paynter, Esq. 24 Betsy E. Lehrfeld, Esq. David W. Dulabon, Esq. Chrstopher B. Turner, Esq. 25 Elizabeth N ach, Esq. Swankin & Turner Wiliam H. Efron, Esq. 1400 16th Street, NW, Suite 101 26 Federal Trade Commission - Northeast Region Washington, DC 20036 27 One Bowling Green, Suite 318 New York, NY 10004 28 Complaint Counsel Counsel for Respondents 1 2 (PROPOSED) ORDER 3 The parties having agreed that Exhibit 1 to Exhibit R18 consists of THE JOURNAL OF THE 4 AMERICAN BOTANICAL COUNCIL, "HerbaIGram," No. 81 (Feb-Apr 2009), 5 6 IT is ORDERED that 7 To the extent it is necessary to change the hearing record such that Exhibit 1 to Exhibit 8 R18 shall consist of THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN BOTANICAL COUNCIL, "HerbaIGram," No.