Late Prehistoric Period, 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Little Clovis Point That Wasn't

The Little Clovis Point that Wasn’t Leo Pettipas Manitoba Archaeological Society The projectile point illustrated in Figure 1 was surface-found at FaMi-10 in the Upper Swan River valley of Manitoba (Fig. 2) in the 1960s. It is made of Swan River Chert, is edge-ground, triangular in outline, and seems to be “fluted” on one face. To all appearances it looks like an Early Indigenous (“Palaeo-Indian”) Clovis point, except for one thing – it’s very small: it’s less than 4.0 cm long, whereas “full-grown” Clovis points when newly made can reach as much as 10.0 cm in length. Archaeologist Eugene Gryba has cautiously classified it as a McKean point, and in size and shape it is indeed McKean- like. However, the bilateral grinding it displays isn’t a standard McKean trait, so I have chosen to orient this presentation around the Clovis point type. Fig. 1. (left)The miniscule point from FaMi-10. Drawing by the present writer. Fig. 2. (Right) Location of the Swan River valley in regional context (Manitoba Department of Agriculture). Actually, bona fide diminutive Clovis points are not unprecedented; several good examples (Fig. 3) were archaeologically excavated in company with typical Clovis points at the Lehner Mammoth site in Arizona. The centre specimen in Figure 3 is 3.6 cm long, slightly less than the corresponding measurement taken from the Swan River artefact. So 1 | P a g e The Little Clovis Point that Wasn’t Leo Pettipas while miniature Clovis points are rare, they’re not unheard of and so the occurrence of one from the Second Prairie Level of Manitoba shouldn’t be problematic at first blush. -

Paleoindian Mobility Ranges Predicted by the Distribution of Projectile Points Made of Upper Mercer and Flint Ridge Flint

Paleoindian Mobility Ranges Predicted by the Distribution of Projectile Points Made of Upper Mercer and Flint Ridge Flint A thesis submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts by Amanda Nicole Mullett December, 2009 Thesis written by Amanda Nicole Mullett B.A. Western State College, 2007 M.A. Kent State University, 2009 Approved by _____________________________, Advisor Dr. Mark F. Seeman _____________________________, Chair, Department of Anthropology Dr. Richard Meindl _____________________________, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences Dr. Timothy Moerland ii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures ............................................................................................................................ v List of Tables ........................................................................................................................... v List of Appendices .................................................................................................................... iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ........................................................................................................... vi Chapter I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................1 II. Background ...................................................................................................................5 The Environment.............................................................................................................5 -

Marking Time

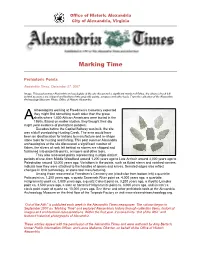

Office of Historic Alexandria City of Alexandria, Virginia Marking Time Prehistoric Points Alexandria Times, December 27, 2007 Image: This past summer Alexandria archaeologists at the site discovered a significant number of flakes, the slivers of rock left behind as stones are chipped and fashioned into projectile points, scrapers and other tools. From the collection of the Alexandria Archaeology Museum. Photo, Office of Historic Alexandria. rchaeologists working at Freedmen’s Cemetery expected they might find something much older than the grave A shafts where 1,800 African-Americans were buried in the 1860s. Based on earlier studies, they thought their dig might yield evidence of prehistoric peoples. Decades before the Capital Beltway was built, the site was a bluff overlooking Hunting Creek. The area would have been an ideal location for Indians to manufacture and re-shape stone tools for hunting and fishing. This past summer Alexandria archaeologists at the site discovered a significant number of flakes, the slivers of rock left behind as stones are chipped and fashioned into projectile points, scrapers and other tools. They also recovered points representing multiple distinct periods of use, from Middle Woodland around 1,200 years ago to Late Archaic around 4,000 years ago to Paleoindian around 13,000 years ago. Variations in the points, such as fluted stems and notched corners, indicate how they were attached to the handles of spears and knives. Serrated edges also reflect changes in lithic technology, or stone tool manufacturing. Among those recovered at Freedmen’s Cemetery are (clockwise from bottom left) a quartzite Potts point ca. -

A Fluted Projectile Point Fragment from the Southern California Coast: Chronology and Context at CA-Sba-1951

UC Merced Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology Title A Fluted Projectile Point Fragment from the Southern California Coast: Chronology and Context at CA-SBa-1951 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4db3j4bm Journal Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology, 9(1) ISSN 0191-3557 Authors Erlandson, Jon M Cooley, Theodore G Carrico, Richard Publication Date 1987-07-01 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California 120 JOURNAL OF CALIFORNIA AND GREAT BASIN ANTHROPOLOGY True, D. L. 1966 Archaeological Differentiation of Sho shonean and Yuman Speaking Groups in A Fluted Projectile Point Fragment Southern California. Ph.D. dissertation. from the Southern California Coast: University of California, Los Angeles. Chronology and Context Vastokas, J. M., and R. K. Vastokas at CA-SBa-1951 1973 Sacred Art of the Algonkians: A Study of the Peterborough Petroglyphs. Peter JON M. ERLANDSON, Dept. of Anthropology, borough, Ontario: Mansard Press. Univ. of California, Santa Barbara, CA 93106. THEODORE G. COOLEY, WESTEC Sendees, WaUace, W. J. Inc., 1221 State Street, Santa Barbara, CA 93101. 1978 Post-Pleistocene Archaeology 9000 to RICHARD CARRICO, WESTEC Services, Inc., 2000 B.C. In: Handbook of the North 5510 Morehouse Drive, San Diego, CA 92121. American Indians, Vol. 8, California, R. F. Heizer, ed., pp. 25-36. Washington: RECENT archaeological research on the Smithsonian Institution. Santa Barbara coast yielded a fragment of a 1986 A Remarkable Group of Carved Stone fluted projectUe point among a larger lithic Objects from Pacific Palisades. Paper assemblage from CA-SBa-1951. The avail presented at the Society for California able data suggest that the fluted point has Southern California Data Sharing Meet no direct temporal relation to the remainder ing, Nov. -

Ohio Archaeologist, 10

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGIST VOLUME 10 OCTOBER, 1960 NUMBER 4 Published by THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF OHIO (Formerly Ohio Indian Relic Collectors Society) The Archaeological Society of Ohio Editorial Office Business Office 420 Chatham Road, Columbus 14, Ohio 65 N. Foster Street, Norwalk, Ohio Tel. AMherst 2-9334 Tel. Norwalk 2-7285 Officers President - Harley W. Glenn, 2011 West Devon Road, Columbus 12, Ohio Vice-President - John C. Allman, 1336 Cory Drive, Dayton 6, Ohio Executive Secretary - Arthur George Smith, 65 North Foster Street, Norwalk, Ohio Corresponding Secretary - Merton R. Mertz, 422 Third Street, Findlay, Ohio Treasurer - Norman L. Dunn, 1205 South West Street, Findlay, Ohio Editor - Ed W. Atkinson, 420-Chatham Road; Columbus 14, Ohio Trustees Gerald Brickman, 409 Locust Street, Findlay, Ohio (Term expire s May, 1961) Thomas A. Minardi, 411 Cline Street, Mansfield, Ohio (Term expire s May, 1961) Emmett W. Barnhart, Northridge Road, Circleville, Ohio (Term expire s May, 1962) John W. Schatz, 80 South Franklin, Hilliards, Ohio (Term expire s May, 1962) Dorothy L. Good, 15 Civic Drive, Grove City, Ohio (Term expire s May, 1963) Wayne A. Mortine, 454 W. State Street, Newcomerstown, Ohio (Term expire s May, 1963) Editorial Staff Editor Ed W. Atkinson, 420 Chatham Road, Columbus 14, Ohio Technical Editor Raymonds. Baby, Ohio State Museum, N. High & 15th, Columbus 10, O. Associate Editor Thyra Bevier Hicks, Ohio State University, Columbus 10, Ohio Assistant Editors John C. Allman, 1336 Cory Drive, Dayton" 6, Ohio H. C. Berg, 262 Walnut Street, Newcomerstown, Ohio Gerald Brickman, 409 Locust Street, Findlay, Ohio Gordon L. Day, Cincinnati Milling Machine Co. -

The Paleoindian Fluted Point: Dart Or Spear Armature?

THE PALEOINDIAN FLUTED POINT: DART OR SPEAR ARMATURE? THE IDENTIFICATION OF PALEOINDIAN DELIVERY TECHNOLOGY THROUGH THE ANALYSIS OF LITHIC FRACTURE VELOCITY BY Wallace Karl Hutchings B.A., Simon Fraser Universis, 1987 M.A., University of Toronto, 199 1 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PMLOSOPHY in the Department of Archaeology O Wallace Karl Hutchings 1997 SIMON FUSER UNIVERSITY November, 2997 Al1 nghts resewed. This work may not be reproduced in whoIe or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. National Library Bibliothèque nationale lJF1 ,,,da du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OrtawaON KIAON4 ûüawaON K1AON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence dowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distnibute or seil reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microfoxm, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/fih, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts ~omit Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. ABSTRACT One of the highest-profile, yet lest known peoples in New World archaeology, are the Paleoindians. -

National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation

NPS Form 10-900-b OMB .vo ion-0018 (Jan 1987) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places JUH151990' Multiple Property Documentation Form NATIONAL REGISTER This form is for use in documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Type all entries. A. Name of Multiple Property Listing___________________________________________ Prehistoric Paleo-Indian Cultures of the Colorado Plains, ca. 11,500-7500 BP B. Associated Historic Contexts_____________________________________________ Sub-context; Clovis Culture; 11,500-11,000 B.P.____________ sub-context: Folsom Culture; 11,000-10,000 B.P. Sub-context; Piano Culture: 10,000-7500 B.P. C. Geographical Data___________________________________________________ The Plains Region of Colorado is that area of the state within the Great Plains Physiographic Province, comprising most of the eastern half of the state (Figure 1). The Colorado Plains is bounded on the north, east and south by the Colorado State Line. On the west, it is bounded by the foothills of the Rocky Mountains. [_]See continuation sheet D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of relaje«kproperties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional renuirifiaejits set forth in 36 CFSKPaV 60 and. -

Paleoindian and Archaic Periods

ADVANCED SOUTHWEST ARCHAEOLOGY THE PALEOINDIAN AND ARCHAIC PERIODS PURPOSE To present members with an opportunity to acquire an in-depth understanding of the Paleoindian and Archaic periods as their occupations are viewed broadly across North America with a focus on the Southwest. OBJECTIVES After studying the manifestation of the Paleoindian and Archaic periods in the Southwest, the student is to have an in-depth understanding of the current thinking regarding: A. Arrival of the first Americans and their adaptation to various environments. Paleoenvironmental considerations. B. Archaeology of the Paleoindian and Archaic periods in the Southwest and important sites for defining and dating the occupations. Synthesis of the Archaic tradition within the Southwest. Manifestation of the Paleoindian and Archaic occupations of the Southwest in the archaeological record, including recognition of Paleoindian and Archaic artifacts and features in situ and recognition of Archaic rock art. C. Subsistence, economy, and settlement strategies of the Paleoindian and Archaic periods in the Southwest. D. Transition from Paleoindian to Archaic, and from Archaic to major cultural traditions including Hohokam, Anasazi, Mogollon, Patayan, and Sinagua, or Salado, in the Southwest. E. Introduction of agriculture in the Southwest considering horticulture and early cultigens. F. Lithic technologies of the Paleoindian and Archaic periods in the Southwest. FORMAT Twenty-five hours of classwork are required to present the class. Ten classes of two and one-half hours -

Paleoindian Period Archaeology of Georgia

University of Georgia Laboratory of Archaeology Series Report No. 28 Georgia Archaeological Research Design Paper No.6 PALEOINDIAN PERIOD ARCHAEOLOGY OF GEORGIA By David G. Anderson National Park Service, Interagency Archaeological Services Division R. Jerald Ledbetter Southeastern Archeological Services and Lisa O'Steen Watkinsville October, 1990 I I I I i I, ...------------------------------- TABLE OF CONTENTS FIGURES ..................................................................................................... .iii TABLES ....................................................................................................... iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .................................................................................. v I. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................... 1 Purpose and Organization of this Plan ........................................................... 1 Environmental Conditions During the PaleoIndian Period .................................... 3 Chronological Considerations ..................................................................... 6 II. PREVIOUS PALEOINDIAN ARCHAEOLOGICAL RESEARCH IN GEORGIA. ......... 10 Introduction ........................................................................................ 10 Initial PaleoIndian Research in Georgia ........................................................ 10 The Early Flint Industry at Macon .......................................................... l0 Early Efforts With Private Collections -

An Archaeological Survey of the Wabash Valley in Illinois

LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY QF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN 507 '• r CENTRAL CIRCULATION BOOKSTACKS The person charging this material is re- sponsible for its renewal or its return to the library from which it was borrowed on or before the Latest Date stamped below. You may be charged a minimum fee of $75.00 for each lost book. are reason* Thoft, imtfOaHM, and underlining of bck. dismissal from for dtelpltaary action and may result In TO RENEW CML TELEPHONE CENTER, 333-8400 UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN APR 2003 MG 1 2 1997 AUG 2 4 2006 AUG 2 3 1999 AUG 13 1999 1ft 07 WO AU6 23 2000 9 10 .\ AUG 242000 Wh^^ie^i^ $$$ae, write new due date below previous due date. 1*162 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/archaeologicalsu10wint Howard D. Winters s AN ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY OFTHE WABASH VALLEYin Illinois mmm* THE 3 1367 . \ Illinois State Museum STATE OF ILLINOIS Otto Kerner, Governor DEPARTMENT OF REGISTRATION AND EDUCATION John C. Watson, Director ILLINOIS STATE MUSEUM Milton D. Thompson, Museum Director REPORTS OF INVESTIGATIONS. No. 10 AN ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF THE WABASH VALLEY IN ILLINOIS by Howard D. Winters Printed by Authority of the State of Illinois Springfield, Illinois 1967 BOARD OF THE ILLINOIS STATE MUSEUM Everett P. Coleman, M.D., Chairman Coleman Clinic, Canton Myers John C.Watson Albert Vice-President, Myers Bros. Director, Department of Springfield Registration and Education Sol Tax, Ph.D., Secretary William Sylvester White of Anthropology Professor Judge, Circuit Court Dean, University Extension Cook County, Chicago University of Chicago Leland Webber C. -

Paleo-Indian Period

OFFICE OF THE STATE ARCHAEOLOGIST EDUCATIONAL SERIES 1 PALEO-INDIAN PERIOD THE EARLIEST PERIOD in Iowa prehistory is sometimes re- ferred to as the “Paleo-Indian” or “Big-Game Hunting” stage. Clovis spearpoint hafted to its shaft. It represents the first time that we find evidence of people living in the state. The remains of even earlier people have been found in North, Central, and South America and sug- gest that the Western Hemisphere was colonized by 20,000 years ago, and possibly earlier. It is believed that the very earliest immigrants entered the New World from Asia at vari- ous times throughout the last “Ice Age,” or Pleistocene ep- och, when vast ice sheets partially covered the northern parts of North America and Eurasia. These ice sheets, or glaciers, locked up thousands of cubic miles of water, thereby lower- ing sea levels on a worldwide scale and exposing many areas of land formerly covered by water. One of these was an area beneath what is now the Bering Strait, a narrow strip of wa- 13,000 years old. They consist of projec- ter that separates northeastern Siberia and western Alaska. It tile points from the Clovis and Folsom is believed that at several times during the Pleistocene when complexes. In Iowa, early Paleo-Indian sea levels were lowered, this area emerged as dry land form- sites tend to be found near streams or riv- ing a broad bridge between the two continents. Across this ers, and are particularly abundant in bridge (sometimes referred to as Beringia) both plant and confluence areas and in areas of high quality chert or flint. -

Article Info Abstract

Journal of Archaeological Science 53 (2015) 550e558 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Archaeological Science journal homepage: http://www.elsevier.com/locate/jas Neutron activation analysis of 12,900-year-old stone artifacts confirms 450e510þ km Clovis tool-stone acquisition at Paleo Crossing (33ME274), northeast Ohio, U.S.A. * Matthew T. Boulanger a, b, , Briggs Buchanan c, Michael J. O'Brien b, Brian G. Redmond d, * Michael D. Glascock a, Metin I. Eren b, d, a Archaeometry Laboratory, University of Missouri Research Reactor, Columbia, MO, 65211, USA b Department of Anthropology, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO, 65211, USA c Department of Anthropology, University of Tulsa, Tulsa, OK, 74104, USA d Department of Archaeology, Cleveland Museum of Natural History, Cleveland, OH, 44106-1767, USA article info abstract Article history: The archaeologically sudden appearance of Clovis artifacts (13,500e12,500 calibrated years ago) across Received 30 August 2014 Pleistocene North America documents one of the broadest and most rapid expansions of any culture Received in revised form known from prehistory. One long-asserted hallmark of the Clovis culture and its rapid expansion is the 1 November 2014 long-distance acquisition of “exotic” stone used for tool manufacture, given that this behavior would be Accepted 5 November 2014 consistent with geographically widespread social contact and territorial permeability among mobile Available online 13 November 2014 hunteregatherer populations. Here we present geochemical evidence acquired from neutron activation analysis (NAA) of stone flaking debris from the Paleo Crossing site, a 12,900-year-old Clovis camp in Keywords: Clovis northeastern Ohio. These data indicate that the majority stone raw material at Paleo Crossing originates Colonization from the Wyandotte chert source area in Harrison County, Indiana, a straight-line distance of 450 Long-distance resource acquisition e510 km.