The Hell'n Moriah Clovis Site

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Little Clovis Point That Wasn't

The Little Clovis Point that Wasn’t Leo Pettipas Manitoba Archaeological Society The projectile point illustrated in Figure 1 was surface-found at FaMi-10 in the Upper Swan River valley of Manitoba (Fig. 2) in the 1960s. It is made of Swan River Chert, is edge-ground, triangular in outline, and seems to be “fluted” on one face. To all appearances it looks like an Early Indigenous (“Palaeo-Indian”) Clovis point, except for one thing – it’s very small: it’s less than 4.0 cm long, whereas “full-grown” Clovis points when newly made can reach as much as 10.0 cm in length. Archaeologist Eugene Gryba has cautiously classified it as a McKean point, and in size and shape it is indeed McKean- like. However, the bilateral grinding it displays isn’t a standard McKean trait, so I have chosen to orient this presentation around the Clovis point type. Fig. 1. (left)The miniscule point from FaMi-10. Drawing by the present writer. Fig. 2. (Right) Location of the Swan River valley in regional context (Manitoba Department of Agriculture). Actually, bona fide diminutive Clovis points are not unprecedented; several good examples (Fig. 3) were archaeologically excavated in company with typical Clovis points at the Lehner Mammoth site in Arizona. The centre specimen in Figure 3 is 3.6 cm long, slightly less than the corresponding measurement taken from the Swan River artefact. So 1 | P a g e The Little Clovis Point that Wasn’t Leo Pettipas while miniature Clovis points are rare, they’re not unheard of and so the occurrence of one from the Second Prairie Level of Manitoba shouldn’t be problematic at first blush. -

A Comprehensive Ecological Land Classification for Utah's West Desert

Western North American Naturalist Volume 65 Number 3 Article 1 7-28-2005 A comprehensive ecological land classification for Utah's West Desert Neil E. West Utah State University Frank L. Dougher Utah State University and Montana State University, Bozeman Gerald S. Manis Utah State University R. Douglas Ramsey Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/wnan Recommended Citation West, Neil E.; Dougher, Frank L.; Manis, Gerald S.; and Ramsey, R. Douglas (2005) "A comprehensive ecological land classification for Utah's West Desert," Western North American Naturalist: Vol. 65 : No. 3 , Article 1. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/wnan/vol65/iss3/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Western North American Naturalist Publications at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Western North American Naturalist by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Western North American Naturalist 65(3), © 2005, pp. 281–309 A COMPREHENSIVE ECOLOGICAL LAND CLASSIFICATION FOR UTAH’S WEST DESERT Neil E. West1, Frank L. Dougher1,2, Gerald S. Manis1,3, and R. Douglas Ramsey1 ABSTRACT.—Land managers and scientists need context in which to interpolate between or extrapolate beyond discrete field points in space and time. Ecological classification of land (ECL) is one way by which these relationships can be made. Until regional issues emerged and calls were made for ecosystem management (EM), each land management institution chose its own ECLs. The need for economic efficiency and the increasing availability of geographic informa- tion systems (GIS) compel the creation of a national ECL so that communication across ownership boundaries can occur. -

Paleoindian Mobility Ranges Predicted by the Distribution of Projectile Points Made of Upper Mercer and Flint Ridge Flint

Paleoindian Mobility Ranges Predicted by the Distribution of Projectile Points Made of Upper Mercer and Flint Ridge Flint A thesis submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts by Amanda Nicole Mullett December, 2009 Thesis written by Amanda Nicole Mullett B.A. Western State College, 2007 M.A. Kent State University, 2009 Approved by _____________________________, Advisor Dr. Mark F. Seeman _____________________________, Chair, Department of Anthropology Dr. Richard Meindl _____________________________, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences Dr. Timothy Moerland ii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures ............................................................................................................................ v List of Tables ........................................................................................................................... v List of Appendices .................................................................................................................... iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ........................................................................................................... vi Chapter I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................1 II. Background ...................................................................................................................5 The Environment.............................................................................................................5 -

Quaternary Tectonics of Utah with Emphasis on Earthquake-Hazard Characterization

QUATERNARY TECTONICS OF UTAH WITH EMPHASIS ON EARTHQUAKE-HAZARD CHARACTERIZATION by Suzanne Hecker Utah Geologiral Survey BULLETIN 127 1993 UTAH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY a division of UTAH DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES 0 STATE OF UTAH Michael 0. Leavitt, Governor DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES Ted Stewart, Executive Director UTAH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY M. Lee Allison, Director UGSBoard Member Representing Lynnelle G. Eckels ................................................................................................... Mineral Industry Richard R. Kennedy ................................................................................................. Civil Engineering Jo Brandt .................................................................................................................. Public-at-Large C. Williatn Berge ...................................................................................................... Mineral Industry Russell C. Babcock, Jr.............................................................................................. Mineral Industry Jerry Golden ............................................................................................................. Mineral Industry Milton E. Wadsworth ............................................................................................... Economics-Business/Scientific Scott Hirschi, Director, Division of State Lands and Forestry .................................... Ex officio member UGS Editorial Staff J. Stringfellow ......................................................................................................... -

Water Resources of Millard County, Utah

WATER RESOURCES OF MILLARD COUNTY, UTAH by Fitzhugh D. Davis Utah Geological Survey, retired OPEN-FILE REPORT 447 May 2005 UTAH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY a division of UTAH DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES Although this product represents the work of professional scientists, the Utah Department of Natural Resources, Utah Geological Survey, makes no warranty, stated or implied, regarding its suitability for a particular use. The Utah Department of Natural Resources, Utah Geological Survey, shall not be liable under any circumstances for any direct, indirect, special, incidental, or consequential damages with respect to claims by users of this product. This Open-File Report makes information available to the public in a timely manner. It may not conform to policy and editorial standards of the Utah Geological Survey. Thus it may be premature for an individual or group to take action based on its contents. WATER RESOURCES OF MILLARD COUNTY, UTAH by Fitzhugh D. Davis Utah Geological Survey, retired 2005 This open-file release makes information available to the public in a timely manner. It may not conform to policy and editorial standards of the Utah Geological Survey. Thus it may be premature for an individual or group to take action based on its contents. Although this product is the work of professional scientists, the Utah Department of Natural Resources, Utah Geological Survey, makes no warranty, expressed or implied, regarding its suitability for a particular use. The Utah Department of Natural Resources, Utah Geological Survey, shall not be liable under any circumstances for any direct, indirect, special, incidental, or consequential damages with respect to claims by users of this product. -

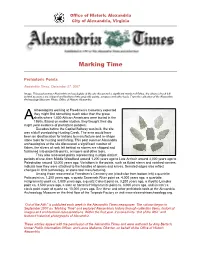

Marking Time

Office of Historic Alexandria City of Alexandria, Virginia Marking Time Prehistoric Points Alexandria Times, December 27, 2007 Image: This past summer Alexandria archaeologists at the site discovered a significant number of flakes, the slivers of rock left behind as stones are chipped and fashioned into projectile points, scrapers and other tools. From the collection of the Alexandria Archaeology Museum. Photo, Office of Historic Alexandria. rchaeologists working at Freedmen’s Cemetery expected they might find something much older than the grave A shafts where 1,800 African-Americans were buried in the 1860s. Based on earlier studies, they thought their dig might yield evidence of prehistoric peoples. Decades before the Capital Beltway was built, the site was a bluff overlooking Hunting Creek. The area would have been an ideal location for Indians to manufacture and re-shape stone tools for hunting and fishing. This past summer Alexandria archaeologists at the site discovered a significant number of flakes, the slivers of rock left behind as stones are chipped and fashioned into projectile points, scrapers and other tools. They also recovered points representing multiple distinct periods of use, from Middle Woodland around 1,200 years ago to Late Archaic around 4,000 years ago to Paleoindian around 13,000 years ago. Variations in the points, such as fluted stems and notched corners, indicate how they were attached to the handles of spears and knives. Serrated edges also reflect changes in lithic technology, or stone tool manufacturing. Among those recovered at Freedmen’s Cemetery are (clockwise from bottom left) a quartzite Potts point ca. -

A Fluted Projectile Point Fragment from the Southern California Coast: Chronology and Context at CA-Sba-1951

UC Merced Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology Title A Fluted Projectile Point Fragment from the Southern California Coast: Chronology and Context at CA-SBa-1951 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4db3j4bm Journal Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology, 9(1) ISSN 0191-3557 Authors Erlandson, Jon M Cooley, Theodore G Carrico, Richard Publication Date 1987-07-01 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California 120 JOURNAL OF CALIFORNIA AND GREAT BASIN ANTHROPOLOGY True, D. L. 1966 Archaeological Differentiation of Sho shonean and Yuman Speaking Groups in A Fluted Projectile Point Fragment Southern California. Ph.D. dissertation. from the Southern California Coast: University of California, Los Angeles. Chronology and Context Vastokas, J. M., and R. K. Vastokas at CA-SBa-1951 1973 Sacred Art of the Algonkians: A Study of the Peterborough Petroglyphs. Peter JON M. ERLANDSON, Dept. of Anthropology, borough, Ontario: Mansard Press. Univ. of California, Santa Barbara, CA 93106. THEODORE G. COOLEY, WESTEC Sendees, WaUace, W. J. Inc., 1221 State Street, Santa Barbara, CA 93101. 1978 Post-Pleistocene Archaeology 9000 to RICHARD CARRICO, WESTEC Services, Inc., 2000 B.C. In: Handbook of the North 5510 Morehouse Drive, San Diego, CA 92121. American Indians, Vol. 8, California, R. F. Heizer, ed., pp. 25-36. Washington: RECENT archaeological research on the Smithsonian Institution. Santa Barbara coast yielded a fragment of a 1986 A Remarkable Group of Carved Stone fluted projectUe point among a larger lithic Objects from Pacific Palisades. Paper assemblage from CA-SBa-1951. The avail presented at the Society for California able data suggest that the fluted point has Southern California Data Sharing Meet no direct temporal relation to the remainder ing, Nov. -

Hydrogeologic and Geochemical Characterization of Groundwater Resources in Pine and Wah Wah Valleys, Iron, Beaver, and Millard Counties, Utah

Hydrogeologic and Geochemical Characterization of Groundwater Resources in Pine and Wah Wah Valleys, Iron, Beaver, and Millard Counties, Utah Prepared by Phillip Gardner, USGS Presented by Thomas Marston, USGS Funding by CICWCD, Bureau of Land Management, Utah Division of Water Rights, USGS Cooperative Water Program Study Objectives • Better understand the groundwater system • Establish baseline hydrologic data - natural variation at selected springs and wells • Evaluate the hydrologic connection between mountain springs & valley aquifers • Use new data to update - conceptual model - groundwater budget via GBCAAS numerical model Approach 1) Monitor spring discharge 2) Well & water level inventory: potentiometric map 3) Update regional groundwater ET estimates: Sevier Lake playa and Tule Valley 4) Geochemistry & environmental tracers - Ages - Flow paths - Sources - Connection between mountain springs and valley aquifers 5) Perform two, multi-well 7-day aquifer tests (1 in each valley) 6) Update GBCAAS numerical model 7) Update groundwater budget estimate Long-term water level trends 566 567 1 568 569 570 662 664 666 2 668 670 4 232 233 3 3 234 235 236 434 1 435 4 2 436 5 437 438 364 365 5 366 367 368 Jan-74 Jan-76 Jan-78 Jan-80 Jan-82 Jan-84 Jan-86 Jan-88 Jan-90 Jan-92 Jan-94 Jan-96 Jan-98 Jan-00 Jan-02 Jan-04 Jan-06 Jan-08 Jan-10 Jan-12 Jan-14 All levels up since 1983 - 1984 Updated water-level data Update based on: • 25 new USGS water levels • 3 reported drillers levels • Utah Alunite water levels • Peak Minerals /CH2MHill levels • Pine -

Ohio Archaeologist, 10

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGIST VOLUME 10 OCTOBER, 1960 NUMBER 4 Published by THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF OHIO (Formerly Ohio Indian Relic Collectors Society) The Archaeological Society of Ohio Editorial Office Business Office 420 Chatham Road, Columbus 14, Ohio 65 N. Foster Street, Norwalk, Ohio Tel. AMherst 2-9334 Tel. Norwalk 2-7285 Officers President - Harley W. Glenn, 2011 West Devon Road, Columbus 12, Ohio Vice-President - John C. Allman, 1336 Cory Drive, Dayton 6, Ohio Executive Secretary - Arthur George Smith, 65 North Foster Street, Norwalk, Ohio Corresponding Secretary - Merton R. Mertz, 422 Third Street, Findlay, Ohio Treasurer - Norman L. Dunn, 1205 South West Street, Findlay, Ohio Editor - Ed W. Atkinson, 420-Chatham Road; Columbus 14, Ohio Trustees Gerald Brickman, 409 Locust Street, Findlay, Ohio (Term expire s May, 1961) Thomas A. Minardi, 411 Cline Street, Mansfield, Ohio (Term expire s May, 1961) Emmett W. Barnhart, Northridge Road, Circleville, Ohio (Term expire s May, 1962) John W. Schatz, 80 South Franklin, Hilliards, Ohio (Term expire s May, 1962) Dorothy L. Good, 15 Civic Drive, Grove City, Ohio (Term expire s May, 1963) Wayne A. Mortine, 454 W. State Street, Newcomerstown, Ohio (Term expire s May, 1963) Editorial Staff Editor Ed W. Atkinson, 420 Chatham Road, Columbus 14, Ohio Technical Editor Raymonds. Baby, Ohio State Museum, N. High & 15th, Columbus 10, O. Associate Editor Thyra Bevier Hicks, Ohio State University, Columbus 10, Ohio Assistant Editors John C. Allman, 1336 Cory Drive, Dayton" 6, Ohio H. C. Berg, 262 Walnut Street, Newcomerstown, Ohio Gerald Brickman, 409 Locust Street, Findlay, Ohio Gordon L. Day, Cincinnati Milling Machine Co. -

The Paleoindian Fluted Point: Dart Or Spear Armature?

THE PALEOINDIAN FLUTED POINT: DART OR SPEAR ARMATURE? THE IDENTIFICATION OF PALEOINDIAN DELIVERY TECHNOLOGY THROUGH THE ANALYSIS OF LITHIC FRACTURE VELOCITY BY Wallace Karl Hutchings B.A., Simon Fraser Universis, 1987 M.A., University of Toronto, 199 1 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PMLOSOPHY in the Department of Archaeology O Wallace Karl Hutchings 1997 SIMON FUSER UNIVERSITY November, 2997 Al1 nghts resewed. This work may not be reproduced in whoIe or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. National Library Bibliothèque nationale lJF1 ,,,da du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OrtawaON KIAON4 ûüawaON K1AON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence dowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distnibute or seil reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microfoxm, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/fih, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts ~omit Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. ABSTRACT One of the highest-profile, yet lest known peoples in New World archaeology, are the Paleoindians. -

National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation

NPS Form 10-900-b OMB .vo ion-0018 (Jan 1987) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places JUH151990' Multiple Property Documentation Form NATIONAL REGISTER This form is for use in documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Type all entries. A. Name of Multiple Property Listing___________________________________________ Prehistoric Paleo-Indian Cultures of the Colorado Plains, ca. 11,500-7500 BP B. Associated Historic Contexts_____________________________________________ Sub-context; Clovis Culture; 11,500-11,000 B.P.____________ sub-context: Folsom Culture; 11,000-10,000 B.P. Sub-context; Piano Culture: 10,000-7500 B.P. C. Geographical Data___________________________________________________ The Plains Region of Colorado is that area of the state within the Great Plains Physiographic Province, comprising most of the eastern half of the state (Figure 1). The Colorado Plains is bounded on the north, east and south by the Colorado State Line. On the west, it is bounded by the foothills of the Rocky Mountains. [_]See continuation sheet D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of relaje«kproperties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional renuirifiaejits set forth in 36 CFSKPaV 60 and. -

Paleoindian and Archaic Periods

ADVANCED SOUTHWEST ARCHAEOLOGY THE PALEOINDIAN AND ARCHAIC PERIODS PURPOSE To present members with an opportunity to acquire an in-depth understanding of the Paleoindian and Archaic periods as their occupations are viewed broadly across North America with a focus on the Southwest. OBJECTIVES After studying the manifestation of the Paleoindian and Archaic periods in the Southwest, the student is to have an in-depth understanding of the current thinking regarding: A. Arrival of the first Americans and their adaptation to various environments. Paleoenvironmental considerations. B. Archaeology of the Paleoindian and Archaic periods in the Southwest and important sites for defining and dating the occupations. Synthesis of the Archaic tradition within the Southwest. Manifestation of the Paleoindian and Archaic occupations of the Southwest in the archaeological record, including recognition of Paleoindian and Archaic artifacts and features in situ and recognition of Archaic rock art. C. Subsistence, economy, and settlement strategies of the Paleoindian and Archaic periods in the Southwest. D. Transition from Paleoindian to Archaic, and from Archaic to major cultural traditions including Hohokam, Anasazi, Mogollon, Patayan, and Sinagua, or Salado, in the Southwest. E. Introduction of agriculture in the Southwest considering horticulture and early cultigens. F. Lithic technologies of the Paleoindian and Archaic periods in the Southwest. FORMAT Twenty-five hours of classwork are required to present the class. Ten classes of two and one-half hours