Dr. Leonard L. Heston, M.D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

American Intelligence and the Question of Hitler's Death

American Intelligence and the Question of Hitler’s Death Undergraduate Research Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with honors research distinction in History in the Undergraduate colleges of The Ohio State University by Kelsey Mullen The Ohio State University November 2014 Project Advisor: Professor Alice Conklin, Department of History Project Mentor: Doctoral Candidate Sarah K. Douglas, Department of History American Intelligence and the Question of Hitler’s Death 2 Introduction The fall of Berlin marked the end of the European theatre of the Second World War. The Red Army ravaged the city and laid much of it to waste in the early days of May 1945. A large portion of Hitler’s inner circle, including the Führer himself, had been holed up in the Führerbunker underneath the old Reich Chancellery garden since January of 1945. Many top Nazi Party officials fled or attempted to flee the city ruins in the final moments before their destruction at the Russians’ hands. When the dust settled, the German army’s capitulation was complete. There were many unanswered questions for the Allies of World War II following the Nazi surrender. Invading Russian troops, despite recovering Hitler’s body, failed to disclose this fact to their Allies when the battle ended. In September of 1945, Dick White, the head of counter intelligence in the British zone of occupation, assigned a young scholar named Hugh Trevor- Roper to conduct an investigation into Hitler’s last days in order to refute the idea the Russians promoted and perpetuated that the Führer had escaped.1 Major Trevor-Roper began his investigation on September 18, 1945 and presented his conclusions to the international press on November 1, 1945. -

Whose Hi/Story Is It? the U.S. Reception of Downfall

Whose Hi/story Is It? The U.S. Reception of Downfall David Bathrick Before I address the U.S. media response to the fi lm Downfall, I would like to mention a methodological problem that I encountered time and again when researching this essay: whether it is possible to speak of reception in purely national terms in this age of globalization, be it a foreign fi lm or any other cultural artifact. Generally speaking, Bernd Eichinger’s large-scale production Downfall can be considered a success in America both fi nancially and critically. On its fi rst weekend alone in New York City it broke box-offi ce records for the small repertory movie theater Film Forum, grossing $24,220, despite its consider- able length, some two and a half hours, and the fact that it was shown in the original with subtitles. Nationally, audience attendance remained unusually high for the following twelve weeks, compared with average fi gures for other German fi lms made for export markets.1 Downfall, which grossed $5,501,940 to the end of October 2005, was an unequivocal box-offi ce hit. One major reason for its success was certainly the content. Adolf Hit- ler, in his capacity as star of the silver screen, has always been a suffi cient This article originally appeared in Das Böse im Blick: Die Gegenwart des Nationalsozialismus im Film, ed. Margrit Frölich, Christian Schneider, and Karsten Visarius (Munich: edition text und kritik, 2007). 1. The only more recent fi lm to earn equivalent revenue was Nirgendwo in Afrika. -

Hitlers Hofstaat Der Innere Kreis Im Dritten Reich Und Danach

Unverkäufliche Leseprobe Heike B. Görtemaker Hitlers Hofstaat Der innere Kreis im Dritten Reich und danach 2019 528 S., mit 62 Abbildungen ISBN 978-3-406-73527-1 Weitere Informationen finden Sie hier: https://www.chbeck.de/26572343 © Verlag C.H.Beck oHG, München Heike B. Görtemaker Hitlers Hofstaat Der innere Kreis im Dritten Reich und danach C.H.Beck Mit 62 Abbildungen © Verlag C.H.Beck oHG, München 2019 Umschlaggestaltung: Kunst oder Reklame, München Umschlagabbildung: Berghof 1935, Hitler und seine Entourage beobachten Kunstfl ieger © Paul Popper / Getty Images Satz: Janß GmbH, Pfungstadt Druck und Bindung: CPI – Ebner & Spiegel, Ulm Gedruckt auf säurefreiem, alterungsbeständigem Papier (hergestellt aus chlorfrei gebleichtem Zellstoff ) Printed in Germany ISBN 978 3 406 73527 1 www.chbeck.de Inhalt Inhalt Einleitung 9 Erster Teil Hitlers Kreis 1. Untergang und Flucht 18 Im Bunker der Reichskanzlei 18 – Absetzbewegungen und Verrat 22 – Zufl uchtsort Berghof 26 – Ende in Berlin 32 2. Die Formierung des Kreises 36 Die Münchner Clique 37 – Ernst Röhm 42 – Hermann Esser und Dietrich Eckart 44 – Alfred Rosenberg 49 – Leibwächter 50 – «Kampfzeit» 53 – Hermann Göring und Wilhelm Brückner 56 – Vorbild Mussolini 59 – Ernst Hanfstaengl 63 – Heinrich Hoff mann 64 – «Stoßtrupp Hitler» 67 – Bayreuth 71 – Putsch 75 – Landsberg 79 – Neuorientierung 83 – Wiedergründung der NSDAP 88 – Joseph Goebbels 93 3. Machtübernahme 97 Aufstieg 98 – Unsicherheit und Beklemmungen 100 – Geli Raubal: Romanze mit dem Onkel 102 – Rekrutierung bewährter Kräfte 108 – Otto Dietrich 112 – Magda Goeb- bels 115 – Das Superwahljahr 1932 122 – Ernüchterung nach der «Machtergreifung» 128 – Blutsommer 1934 133 – Lüdecke auf der Flucht 137 – Hinrichtungen 142 – Recht- fertigungsversuche 148 Zweiter Teil Die Berghof-Gesellschaft 1. -

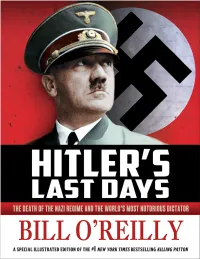

Hitlers-Last-Days-By-Bill-Oreilly-Excerpt

207-60729_ch00_6P.indd ii 7/7/15 8:42 AM Henry Holt and Com pany, LLC Publishers since 1866 175 Fifth Ave nue, New York, New York 10010 macteenbooks . com Henry Holt® is a registered trademark of Henry Holt and Com pany, LLC. Copyright © 2015 by Bill O’Reilly All rights reserved. Permission to use the following images is gratefully acknowledged (additional credits are noted with captions): Mary Evans Picture Library— endpapers, pp. ii, v, vi, 35, 135, 248, 251; Bridgeman Art Library— endpapers, p. iii; Heinrich Hoffman/Getty— p. 1. All maps by Gene Thorp. Case design by Meredith Pratt. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data O’Reilly, Bill. Hitler’s last days : the death of the Nazi regime and the world’s most notorious dictator / Bill O’Reilly. — First edition. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-62779-396-4 (hardcover) • ISBN 978-1-62779-397-1 (e- book) 1. Hitler, Adolf, 1889–1945. 2. Hitler, Adolf, 1889–1945— Death and burial. 3. World War, 1939–1945— Campaigns— Germany. 4. Berlin, Battle of, Berlin, Germany, 1945. 5. Heads of state— Germany— Biography. 6. Dictators— Germany— Biography. I. O’Reilly, Bill. Killing Patton. II. Title. DD247.H5O735 2015 943.086092— dc23 2015000562 Henry Holt books may be purchased for business or promotional use. For information on bulk purchases, please contact the Macmillan Corporate and Premium Sales Department at (800) 221-7945 x5442 or by e-mail at specialmarkets@macmillan . com. First edition—2015 / Designed by Meredith Pratt Based on the book Killing Patton by Bill O’Reilly, published by Henry Holt and Com pany, LLC. -

The Meaning of Health

All letters are subject to editing and may be shortened. Letters of no more than 400 words should be sent to the BJGP office by e-mail in the first instance, addressed to [email protected] (please include your postal address and job title). Alternatively, they may be sent by post (if possible, include a copy on disk). We regret that we Letters cannot always notify authors regarding publication. Fuzzy logic through less interesting times, we can in humdrum routines, or the stiff, see this film as a warning from history. I unyielding logic of somatising patients. find working with a few individuals or Even if the only mortal threat we face is David Jewell finds the journal title Fuzzy enmeshed families seemingly trapped in a double espresso, Downfall is more Optimization and Decision Making a self-destructive fate hard enough, and than a history lesson. incomprehensible,1 while Richard facing it on a societal scale is barely Lehman contrasts fuzzy with logical thinkable. Steve Iliffe thinking.2 Now I have never seen this The German view may be different. FRCGP, Lonsdale Medical Centre, journal, but I would expect it to deal with Downfall is a moral tale of redemption in London. E-mail: [email protected] fuzzy logic, which far from being its different forms, as much docudrama illogical, is an attempt to adapt classical REFERENCE of the battle between rigidity and logic to fit it to deal with a world of ill- 1. Bamforth I. Götterdämmerung in a hole in the flexibility as that between good and evil. -

La Banalidad De Los Recuerdos: La Memoria De Traudl Junge

La banalidad de los recuerdos: la memoria de Traudl Junge José Alberto Moreno El Colegio de México ◆ Time is an ocean of endless tears Derek Walcott; The Capeman El ensayo analiza la función de la culpa- se utilizarán las memorias de Traudl Jun- bilidad en el relato de un testigo que ha ge, secretaria de Adolf Hitler durante la presenciado un episodio histórico trau- caída del Reich. mático. Para ejemplificar dicha relación Palabras clave: memoria, culpabilidad, conmemoración, narrativa, nazismo. Introducción El recuerdo en las sociedades humanas tiene la función de preservar la memoria y, a través de ella, reproducir hechos que nos alienten a encontrar una identidad dentro de un grupo social determinado. La construcción de una identidad colectiva a partir de episodios selectivos es lo que llamamos memoria. Gracias a la memoria, podemos configurar una personalidad y ubicarnos –como individuos– dentro de una familia, una clase social o la so- ciedad en general. Por medio de la manipulación de la memoria se constru- yen las historias patrias y los grandes relatos metahistóricos, construyendo una memoria colectiva cuyos alcances pretenden servir de recuerdos gene- rales para una colectividad determinada. Conservar una memoria con algu- nos recuerdos –escogidos intencionalmente– que influyan para construir tanto las colectividades como las individualidades, favorecen la recreación de un espacio de representación y de expresión de la identidad. 11 Takwá / Núm. 10 / Otoño 2006 / pp. 11-22 Frente a la memoria, el recuerdo es la remembranza personal de epi- sodios individuales o colectivos. Al margen de un recuerdo pretendido como positivo –positivo en la medida en que ayuda a conformar una visión agradable de sí mismo y de la colectividad– emergen recuerdos desagradables que amenazan constantemente a la memoria colectiva, entendida como un espacio de construcciones en interpretación. -

Film-Downfall-2004

1 / 2 Film-downfall-2004 Apr 26, 2018 — 2005 | Nominee: Best Foreign Language Film of the Year ... Downfall's main deficiency is its failure to engage with German (and Germans') .... Sep 16, 2004 — Downfall (German language/International title: Der Untergang) is a 2004 historical war drama chronicling the last ten days of Adolf Hitler's life .... Oct 6, 2009 — Subtitled parodies of Adolf Hitler's last days in the Berlin bunker, as depicted in the 2004 Second World War film Downfall, have become one of .... 15 hours ago — That last point, according to one report, could be the budding franchise's downfall. 13h ago ... In a first for the Marvel Cinematic Universe, the film opened ... he founded in 2004 poised to begin commercial operations next year.. Jamie Foxx and Michael B. Jordan are two men fighting for justice in this powerful true story. A civil rights attorney fights to free a wrongly convicted death row .... Apr 1, 2005 — Downfall Juliane Kühler as Eva Braun and Bruno Ganz as Hitler await the ... Any movie which removes the great dictator from the horrors of the ... Find the latest trailers, breaking news and movie reviews, and links to the best free movies at ... Nominated for an Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film in 2005.. Downfall (2004 film) ... Downfall (German: Der Untergang) is a 2004 German war film directed by Oliver Hirschbiegel, depicting the final ten days of Adolf Hitler's .... Der Untergang(Downfallin English) is a 2004 German-Italian- Austrian historical war drama film depicting the final ten days of Adolf Hitler's rule over Nazi ... -

Friday Film Fest Series to Argue with This Assessment

THE GERMAN SOCIETY’S Screening Hitler – Allen Krumm “Wir sind mit Hitler noch lange nicht fertig.” It is difficult Friday Film Fest Series to argue with this assessment. Why? Perhaps because, as Joachim Fest notes, “History records no phenomenon like him.” In the introduction of his biography, Fest continues: “…No one evoked so much rejoicing, hysteria and expectation of salvation as he; no one so much hate. No one else produced, in a solitary course lasting only a few years, such incredible accelerations in the pace of history. No one else so changed the state of the world and left behind such a wake of ruins as he did.” Jacob Burckhardt said that to be a good historian “…one has to be able to read.” For the present generation his aphorism might be amended to “one has to be able to watch.” People get much of their history from the movies and a prodigious sub-genre of that cinematic history comprises films about Hitler. Notwithstanding his negatives, der Führer disposes of more than a little box office magic, rivaling sex, car crashes and special effects as an audience aphrodisiac and as an enduring source of fascination. Perhaps there is a belief, ala Putzi Hanfstaengel, that if enough is written and filmed about him, and enough people read the books and see the films, future generations will be inoculated; they will be done with Der Untergang him, and a recurrence of such a time will be rendered impossible. Credits: Director: Oliver Hirschbiegel Script: Bernd Eichinger An enthusiastic kinophile, Hitler would be pleased by (based on Joachim Fest’s Der Untergang and Traudl Junge’s Bis zur the number and range of productions inspired by his letzten Stunde) Lebenslauf . -

High Society Women and the Third Reich

Knowledge and Complicity: High Society Women and the Third Reich Lauren Ditty Senior Honors Thesis in History HIST-409-02 History Department Georgetown University Mentored by Professor Stites May 4, 2009 Ditty 2 To the women of the resistance. Ditty 3 Knowledge and Complicity: High Society Women and the Third Reich Table of Contents List of Illustrations..........................................................................................................................4 Introduction.....................................................................................................................................5 Chapter 1: The Emergence of Nazi Reactionary Attitudes and the Ideal Woman........................14 Chapter 2: High Society and Hitler’s Berghof..............................................................................24 Chapter 3: Inside the Concentration Camps and the SS................................................................50 Chapter 4: The Commandant Wives..............................................................................................66 Conclusion.....................................................................................................................................93 Illustrations....................................................................................................................................98 Works Cited.................................................................................................................................114 Ditty 4 List of Illustrations: -

Leseprobe Acht Tage Im

Unverkäufliche Leseprobe Volker Ullrich Acht Tage im Mai Die letzte Woche des Dritten Reiches 2021. 317 S., mit 21 Abbildungen und 1 Karte ISBN 978-3-406-76883-5 Weitere Informationen finden Sie hier: https://www.chbeck.de/31984023 © Verlag C.H.Beck oHG, München Diese Leseprobe ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Sie können gerne darauf verlinken. Mai 1945: Während die Regierung Dönitz nach Flensburg ausweicht, rücken die alliierten Streitkräfte unaufhaltsam weiter vor. Berlin kapitu- liert, in Italien die Heeresgruppe C. Raketenforscher Wernher von Braun wird festgenommen, Marlene Dietrich sucht in Bergen-Belsen nach ihrer Schwester. Es kommt zu einer Selbstmordepidemie und zu Massenver- gewaltigungen. Letzte Todesmärsche, wilde Vertreibungen, abtauchende Nazi-Bonzen, befreite Konzentrationslager – all das gehört zu jener «Lücke zwischen dem Nichtmehr und dem Nochnicht», die Erich Kästner am 7. Mai 1945 in seinem Tagebuch vermerkt. Volker Ullrich, der große Jour- nalist und Hitler-Biograph, hat aus historischen Miniaturen und Mosaik- steinen ein Panorama dieser «Acht Tage im Mai» zusammengefügt, das sich fesselnder liest als mancher âriller. Volker Ullrich ist Historiker und leitete von 1990 bis 2009 bei der Wochen- zeitung «Die Zeit» das Ressort «Politisches Buch». Er hat eine ganze Reihe von einîussreichen historischen Werken vorgelegt, darunter «Die nervöse Großmacht. Aufstieg und Untergang des deutschen Kaiserreichs 1871– 1918» (1997) und die zweibändige Biographie «Adolf Hitler» (2013 und 2018), die auch in mehrere Sprachen übersetzt wurde. Volker Ullrich er- hielt 1992 den Alfred-Kerr-Preis für Literaturkritik und 2008 die Ehren- doktorwürde der Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena. Volker Ullrich ACHT TAGE IM MAI Die letzte Woche des Dritten Reiches C.H.Beck Dieses Buch erschien zuerst 2020 in gebundener Form im Verlag C.H.Beck. -

STAGING HITLER MYTHS a Thesis Presented to The

STAGING HITLER MYTHS ____________________ A Thesis presented to the Graduate School University of Missouri _____________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts __________________ by Judith Lechner Dr. Roger Cook, Thesis Supervisor MAY 2009 The undersigned, appointed by the Dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled STAGING HITLER MYTHS Presented by Judith Lechner A candidate for the degree of Master of Arts in German. And hereby certify that in their opinion it is worthy of acceptance. __________________________________________ Professor Roger Cook __________________________________________ Professor Sean Franzel __________________________________________ Professor Andrew Hoberek ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I hereby want to thank the professors of my department and Professor Andrew Hoberek from the English Department for their support throughout my writing process. I want to thank Professor Bradley Prager, who first introduced me to this topic in his class about contemporary German cinema and supported me with articles, secondary literature and cause for thought. Furthermore, I want to thank Professor Roger Cook for spontaneously becoming my thesis supervisor. His support throughout the writing process helped me develop a strong thesis and explore my argument. I would also like to thank Professor Sean Franzel for his very helpful comments on the structure of the thesis. Through his comments, the logic of my argument improved. Last but not least, I want to thank Professor Hoberek for joining my -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. U M I films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or p o o r quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UM I directly to order. University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Com pany 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 I I 73-6537 BOONE, Jr., Jasper C., 1935- THE OBERSALZBERG: A CASE STUDY IN NATIONAL SOCIALISM.