The Question of Henotheism (A Contribution to the Study of the Problem of the Origin of All Religions)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

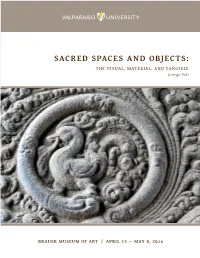

SACRED SPACES and OBJECTS: the VISUAL, MATERIAL, and TANGIBLE George Pati

SACRED SPACES AND OBJECTS: THE VISUAL, MATERIAL, AND TANGIBLE George Pati BRAUER MUSEUM OF ART | APRIL 13 — MAY 8, 2016 WE AT THE BRAUER MUSEUM are grateful for the opportunity to present this exhibition curated by George Pati, Ph.D., Surjit S. Patheja Chair in World Religions and Ethics and Valparaiso University associate professor of theology and international studies. Through this exhibition, Professor Pati shares the fruits of his research conducted during his recent sabbatical and in addition provides valuable insights into sacred objects, sites, and practices in India. Professor Pati’s photographs document specific places but also reflect a creative eye at work; as an artist, his documents are also celebrations of the particular spaces that inspire him and capture his imagination. Accompanying the images in the exhibition are beautiful textiles and objects of metalware that transform the gallery into its own sacred space, with respectful and reverent viewing becoming its own ritual that could lead to a fuller understanding of the concepts Pati brings to our attention. Professor Pati and the Brauer staff wish to thank the Surjit S. Patheja Chair in World Religions and Ethics and the Partners for the Brauer Museum of Art for support of this exhibition. In addition, we wish to thank Gretchen Buggeln and David Morgan for the insights and perspectives they provide in their responses to Pati's essay and photographs. Gregg Hertzlieb, Director/Curator Brauer Museum of Art 2 | BRAUER MUSEUM OF ART SACRED SPACES AND OBJECTS: THE VISUAL, MATERIAL, AND TANGIBLE George Pati George Pati, Ph.D., Valparaiso University Śvetāśvatara Upaniṣad 6:23 Only in a man who has utmost devotion for God, and who shows the same devotion for teacher as for God, These teachings by the noble one will be illuminating. -

Liar, Lunatic, and Lord Compiled from Mere Christianity by C.S Lewis

WHO DO YOU SAY THAT I AM? C.S. Lewis' Lord, Liar, or Lunatic? ––compiled from Mere Christianity C.S. Lewis said this: “Let us not say, ‘I'm ready to accept Jesus as a great moral teacher, but I don't accept his claim to be God.’ That is one thing we must not say. "A man who was merely a man and said the sort of things Jesus said would not be a great moral teacher. He would either be a lunatic--on the level with the man who says he is a poached egg-- or else he would be the Devil of Hell. You must make your choice. Either this man was, and is, the Son of God: or else a madman or something worse. You can shut Him up for a fool, you can spit at Him and kill Him as a demon; or you can fall at His feet and call Him Lord and God. But let us not come with any patronizing nonsense about His being a great moral teacher. He has not left that open to us. He did not intend to.” I. The Question: Who was (is) Jesus? The Main Argument: AThere are only 3 possible answers A Lord, or Liar, or Lunatic. The bottom line of the argument is this: Jesus was either a liar, a lunatic, or the Lord. He could not possibly be a liar or a lunatic. Therefore “Jesus is Lord.” II. Argument #1- The Dilemma: Lord or liar: Jesus was either God (if he did not lie about who he was) or a bad man (if he did). -

A Study of the Early Vedic Age in Ancient India

Journal of Arts and Culture ISSN: 0976-9862 & E-ISSN: 0976-9870, Volume 3, Issue 3, 2012, pp.-129-132. Available online at http://www.bioinfo.in/contents.php?id=53. A STUDY OF THE EARLY VEDIC AGE IN ANCIENT INDIA FASALE M.K.* Department of Histroy, Abasaheb Kakade Arts College, Bodhegaon, Shevgaon- 414 502, MS, India *Corresponding Author: Email- [email protected] Received: December 04, 2012; Accepted: December 20, 2012 Abstract- The Vedic period (or Vedic age) was a period in history during which the Vedas, the oldest scriptures of Hinduism, were composed. The time span of the period is uncertain. Philological and linguistic evidence indicates that the Rigveda, the oldest of the Vedas, was com- posed roughly between 1700 and 1100 BCE, also referred to as the early Vedic period. The end of the period is commonly estimated to have occurred about 500 BCE, and 150 BCE has been suggested as a terminus ante quem for all Vedic Sanskrit literature. Transmission of texts in the Vedic period was by oral tradition alone, and a literary tradition set in only in post-Vedic times. Despite the difficulties in dating the period, the Vedas can safely be assumed to be several thousands of years old. The associated culture, sometimes referred to as Vedic civilization, was probably centred early on in the northern and northwestern parts of the Indian subcontinent, but has now spread and constitutes the basis of contemporary Indian culture. After the end of the Vedic period, the Mahajanapadas period in turn gave way to the Maurya Empire (from ca. -

Shadows of Being

Shadows of Being Shadows of Being Four Philosophical Essays By Marko Uršič Shadows of Being: Four Philosophical Essays By Marko Uršič This book first published 2018 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2018 by Marko Uršič All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-1593-1 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-1593-2 To my dear parents Mila and Stanko who gave me life Just being alive! —miraculous to be in cherry blossom shadows! Kobayashi Issa 斯う活て 居るも不思議ぞ 花の陰 一茶 Kō ikite iru mo fushigi zo hana no kage TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures............................................................................................. ix Acknowledgements .................................................................................... xi Chapter One ................................................................................................. 1 Shadows of Ideas 1.1 Metaphysical essence of shadow, Platonism.................................... 2 1.2 The Sun and shadows in Ancient Egypt .......................................... 6 1.3 From Homeric to Orphic shadows ................................................. 15 Chapter Two ............................................................................................. -

The Political-Economy Trilemma

DPRIETI Discussion Paper Series 20-E-018 The Political-Economy Trilemma AIZENMAN, Joshua University of Southern California and NBER ITO, Hiroyuki RIETI The Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry https://www.rieti.go.jp/en/ RIETI Discussion Paper Series 20-E-018 March 2020 The Political-Economy Trilemma1 Joshua Aizenman University of Southern California and NBER Hiro Ito Portland State University Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry Abstract This paper investigates the political-economy trilemma: policy makers face a trade-off of choosing two out of three policy goals or governance styles, namely, (hyper-)globalization, national sovereignty, and democracy. We develop a set of indexes that measure the extent of attainment of the three factors for 139 countries in the period of 1975-2016. Using these indexes, we examine the validity of the hypothesis of the political-economy trilemma by testing whether the three trilemma variables are linearly related. We find that, for industrialized countries, there is a linear relationship between globalization and national sovereignty (i.e., a dilemma), and that for developing countries, all three indexes are linearly correlated (i.e., a trilemma). We also investigate whether and how three political-economic factors affect the degree of political and financial stability. The results indicate that more democratic industrialized countries tend to experience more political instability, while developing countries tend to be able to stabilize their politics if they are more democratic. The lower level of national sovereignty an industrialized country attains, the more stable its political situation tends to be, while a higher level of sovereignty helps a developing country to stabilize its politics. -

New Measures of the Trilemma Hypothesis: Implications for Asia

ADBI Working Paper Series New Measures of the Trilemma Hypothesis: Implications for Asia Hiro Ito and Masahiro Kawai No. 381 September 2012 Asian Development Bank Institute Hiro Ito is associate professor of economics at the Department of Economics, Portland State University. Masahiro Kawai is Dean and CEO, Asian Development Bank Institute, Tokyo, Japan. This is a revised version of the paper presented to the Asian Development Bank Institute (ADBI) Annual Conference held in Tokyo on 2 December 2011. The authors thank Akira Kohsaka, Guonan Ma, and other conference participants as well as Giovanni Capannelli, Mario B. Lamberte, Eduardo Levy-Yeyati, Peter Morgan, Naoto Osawa, Gloria O. Pasadilla, Reza Siregar, and Willem Thorbecke for useful comments on earlier versions. Michael Cui, Jacinta Bernadette Rico, Erica Clower, and Shigeru Akiyama provided excellent research assistance. The first author thanks Portland State University for financial support and ADBI for its hospitality while he was visiting the institute. The authors accept responsibility for any remaining errors in the paper. The views expressed in this paper are the views of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of ADBI, the ADB, its Board of Directors, or the governments they represent. ADBI does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this paper and accepts no responsibility for any consequences of their use. Terminology used may not necessarily be consistent with ADB official terms. The Working Paper series is a continuation of the formerly named Discussion Paper series; the numbering of the papers continued without interruption or change. ADBI’s working papers reflect initial ideas on a topic and are posted online for discussion. -

Critical Analysis of Views on God's

5th International Conference on Research in Behavioral and Social Science Spain | Barcelona | December 7-9, 2018 Beyond the Barriers of Nature: Critical analysis of views on God’s Existence in various religions R. Rafique, N. Abas Department of Electrical Engineering, University of Gujrat, Hafiz Hayat Campus, Gujrat Abstract: This article reports critical overview of views on existence of God and naturalism. Theists argue the existence of God, atheists insist nonexistence of God, while agnostics claim the existence of God is unknowable, and even if exists, it is neither possible to demonstrate His existence nor likely to refute this spiritual theology. The argument that the existence of God can be known to all, even before exposure to any divine revelation, predates before Islam, Christianity and even Judaism. Pharos deity claim shows that the concept of deity existed long before major religions. History shows the Greek philosophers also tried to explore God before, during and after the prophet’s revolution in Mesopotamia. Today presupposition apologetical doctrine (Abram Kuyper) ponders and defends the existence of God. They conclude the necessary condition of belief to be exposed to revelation that atheists deny calling transcendental necessity. Human experience and action is proof of God’s existence as His existence is the necessary condition of human being’s intelligibility. The spirituality exists in all human sub-consciousness and sometimes, reveals to consciousness of some individuals. Human being’s inability to conceive the cosmos shows that there exist more types of creatures in different parts of universe. Enlightened men’s capability to resurrect corpse proves soul’s immortality. -

JOSHUA L. MOSS Source: Melilah: Atheism, Scepticism and Challenges to Mono

EDITOR Daniel R. Langton ASSISTANT EDITOR Simon Mayers Title: Satire, Monotheism and Scepticism Author(s): JOSHUA L. MOSS Source: Melilah: Atheism, Scepticism and Challenges to Monotheism, Vol. 12 (2015), pp. 14-21 Published by: University of Manchester and Gorgias Press URL: http://www.melilahjournal.org/p/2015.html ISBN: 978-1-4632-0622-2 ISSN: 1759-1953 A publication of the Centre for Jewish Studies, University of Manchester, United Kingdom. Co-published by SATIRE, MONOTHEISM AND SCEPTICISM Joshua L. Moss* ABSTRACT: The habits of mind which gave Israel’s ancestors cause to doubt the existence of the pagan deities sometimes lead their descendants to doubt the existence of any personal God, however conceived. Monotheism was and is a powerful form of Scepticism. The Hebrew Bible contains notable satires of Paganism, such as Psalm 115 and Isaiah 44 with their biting mockery of idols. Elijah challenged the worshippers of Ba’al to a demonstration of divine power, using satire. The reader knows that nothing will happen in response to the cries of Baal’s worshippers, and laughs. Yet, the worshippers of Israel’s God must also be aware that their own cries for help often go unanswered. The insight that caused Abraham to smash the idols in his father’s shop also shakes the altar erected by Elijah. Doubt, once unleashed, is not easily contained. Scepticism is a natural part of the Jewish experience. In the middle ages Jews were non-believers and dissenters as far as the dominant religions were concerned. With the advent of modernity, those sceptical habits of mind could be applied to religion generally, including Judaism. -

C.S. Lewis's Trilemma Seen Through Muslim Eyes

C.S. LEWIS’S TRILEMMA SEEN THROUGH MUSLIM EYES Christian TĂMAȘ Independent Scholar Abstract Beyond his apologetic works about Jesus Christ and the Christian faith, C.S. Lewis polarized the religious and non-religious world with his famous Trilemma expressing his opinion on the nature and identity of Christ. While for the Christians and atheists C.S. Lewis's Trilemma is still a matter of rather harsh debate, for the Muslims it represents a matter of lesser importance. Some of those acquainted with C.S. Lewis's ideas approached it with caution taking into account the Qur’anic statements about the revelations previously “descended” upon man, which generally prevent the Muslims from commenting or interpreting the other monotheistic scriptures. Thus, many Muslim scholars consider C.S. Lewis's Trilemma a Christian affair not of their concern, while others object to its content considered incompatible with the Islamic views concerning the person of Jesus Christ. Keywords: C.S. Lewis, trilemma, Jesus Christ, Islamic Tradition, Qur’an Introduction Considered one of the most influential Christian authors of the past century, C.S. Lewis built a personal theological system starting from the premise that there is a natural law which human beings – necessarily submitted to its influences— must unconditionally accept. Thus, in his opinion, God must exist in His Trinitarian nature as Father, Son and Holy Spirit where the relationship between the Father and Son is the source of divine Love which acts through the Holy Spirit. As a conservative apologist, C.S. Lewis made of the person and the nature of Jesus Christ the central themes of his life and work. -

Hinduism in Time and Space

Introduction: Hinduism in Time and Space Preview as a phenomenon of human culture, hinduism occupies a particular place in time and space. To begin our study of this phenomenon, it is essential to situate it temporally and spatially. We begin by considering how the concept of hinduism arose in the modern era as a way to designate a purportedly coherent system of beliefs and practices. since this initial construction has proven inadequate to the realities of the hindu religious terrain, we adopt “the hindu traditions” as a more satisfactory alternative to "hinduism." The phrase “hindu traditions” calls attention to the great diversity of practices and beliefs that can be described as “hindu.” Those traditions are deeply rooted in history and have flourished almost exclusively on the indian subcontinent within a rich cultural and religious matrix. As strange as it may seem, most Hindus do The Temporal Context not think of themselves as practicing a reli- gion called Hinduism. Only within the last Through most of the millennia of its history, two centuries has it even been possible for the religion we know today as Hinduism has them to think in this way. And although that not been called by that name. The word Hin- possibility now exists, many Hindus—if they duism (or Hindooism, as it was first spelled) even think of themselves as Hindus—do not did not exist until the late eighteenth or early regard “Hinduism” as their “religion.” This irony nineteenth century, when it began to appear relates directly to the history of the concept of sporadically in the discourse of the British Hinduism. -

Proceedings and Addresses of the American Philosophical Association

January 2007 Volume 80, Issue 3 Proceedings and Addresses of The American Philosophical Association apa The AmericAn PhilosoPhicAl Association Pacific Division Program University of Delaware Newark, DE 19716 www.apaonline.org The American Philosophical Association Pacific Division Eighty-First Annual Meeting The Westin St. Francis San Francisco, CA April 3 - 8, 2007 Proceedings and Addresses of The American Philosophical Association Proceedings and Addresses of the American Philosophical Association (ISSN 0065-972X) is published five times each year and is distributed to members of the APA as a benefit of membership and to libraries, departments, and institutions for $75 per year. It is published by The American Philosophical Association, 31 Amstel Ave., University of Delaware, Newark, DE 19716. Periodicals Postage Paid at Newark, DE and additional mailing offices. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Proceedings and Addresses, The American Philosophical Association, University of Delaware, Newark, DE 19716. Editor: David E. Schrader Phone: (302) 831-1112 Publications Coordinator: Erin Shepherd Fax: (302) 831-8690 Associate Editor: Anita Silvers Web: www.apaonline.org Meeting Coordinator: Linda Smallbrook Proceedings and Addresses of The American Philosophical Association, the major publication of The American Philosophical Association, is published five times each academic year in the months of September, November, January, February, and May. Each annual volume contains the programs for the meetings of the three Divisions; the membership list; Presidential Addresses; news of the Association, its Divisions and Committees, and announcements of interest to philosophers. Other items of interest to the community of philosophers may be included by decision of the Editor or the APA Board of Officers. -

Mdm1012le If God Is Good Why Is There Evil

Dear Christian Leader, You are receiving this research brief because you have signed up for free leader equipping ministry resources at markdriscoll.org. I want to personally thank you for loving Jesus and serving his people. I also want to thank you for allowing me the honor of helping you lead and feed God’s people. This research brief is a gift from Mark Driscoll Ministries. It was prepared for me a few years ago by a professional research team. I am happy to make it available to you, and I would request that you not post it online. If you know of other Christian leaders who would like to receive it, they can do so by signing up for for free leadership resources at markdriscoll.org. It’s a great joy helping people learn about Jesus from the Bible, so thank you for allowing me to serve you. If you would be willing to support our ministry with an ongoing or one- time gift of any amount, we would be grateful for your partnership. A Nobody Trying to Tell Everybody About Somebody, Pastor Mark Driscoll 1 21001 NORTH TATUM BLVD | STE 1630-527 | PHOENIX, AZ 85050 | [email protected] MARKDRISCOLL.ORG If God is Good Why is There Evil? Research brief prepared by a research team How can evil or suffering be reconciled with the Christian affirmation of the goodness and power of the God who created the world? The problem of evil is three-legged stool: 1) God is all powerful, 2) God is good, and 3) evil really does exist.