Mdm1012le If God Is Good Why Is There Evil

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shadows of Being

Shadows of Being Shadows of Being Four Philosophical Essays By Marko Uršič Shadows of Being: Four Philosophical Essays By Marko Uršič This book first published 2018 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2018 by Marko Uršič All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-1593-1 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-1593-2 To my dear parents Mila and Stanko who gave me life Just being alive! —miraculous to be in cherry blossom shadows! Kobayashi Issa 斯う活て 居るも不思議ぞ 花の陰 一茶 Kō ikite iru mo fushigi zo hana no kage TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures............................................................................................. ix Acknowledgements .................................................................................... xi Chapter One ................................................................................................. 1 Shadows of Ideas 1.1 Metaphysical essence of shadow, Platonism.................................... 2 1.2 The Sun and shadows in Ancient Egypt .......................................... 6 1.3 From Homeric to Orphic shadows ................................................. 15 Chapter Two ............................................................................................. -

Heavenly Priesthood in the Apocalypse of Abraham

HEAVENLY PRIESTHOOD IN THE APOCALYPSE OF ABRAHAM The Apocalypse of Abraham is a vital source for understanding both Jewish apocalypticism and mysticism. Written anonymously soon after the destruction of the Second Jerusalem Temple, the text envisions heaven as the true place of worship and depicts Abraham as an initiate of the celestial priesthood. Andrei A. Orlov focuses on the central rite of the Abraham story – the scapegoat ritual that receives a striking eschatological reinterpretation in the text. He demonstrates that the development of the sacerdotal traditions in the Apocalypse of Abraham, along with a cluster of Jewish mystical motifs, represents an important transition from Jewish apocalypticism to the symbols of early Jewish mysticism. In this way, Orlov offers unique insight into the complex world of the Jewish sacerdotal debates in the early centuries of the Common Era. The book will be of interest to scholars of early Judaism and Christianity, Old Testament studies, and Jewish mysticism and magic. ANDREI A. ORLOV is Professor of Judaism and Christianity in Antiquity at Marquette University. His recent publications include Divine Manifestations in the Slavonic Pseudepigrapha (2009), Selected Studies in the Slavonic Pseudepigrapha (2009), Concealed Writings: Jewish Mysticism in the Slavonic Pseudepigrapha (2011), and Dark Mirrors: Azazel and Satanael in Early Jewish Demonology (2011). Downloaded from Cambridge Books Online by IP 130.209.6.50 on Thu Aug 08 23:36:19 WEST 2013. http://ebooks.cambridge.org/ebook.jsf?bid=CBO9781139856430 Cambridge Books Online © Cambridge University Press, 2013 HEAVENLY PRIESTHOOD IN THE APOCALYPSE OF ABRAHAM ANDREI A. ORLOV Downloaded from Cambridge Books Online by IP 130.209.6.50 on Thu Aug 08 23:36:19 WEST 2013. -

JOSHUA L. MOSS Source: Melilah: Atheism, Scepticism and Challenges to Mono

EDITOR Daniel R. Langton ASSISTANT EDITOR Simon Mayers Title: Satire, Monotheism and Scepticism Author(s): JOSHUA L. MOSS Source: Melilah: Atheism, Scepticism and Challenges to Monotheism, Vol. 12 (2015), pp. 14-21 Published by: University of Manchester and Gorgias Press URL: http://www.melilahjournal.org/p/2015.html ISBN: 978-1-4632-0622-2 ISSN: 1759-1953 A publication of the Centre for Jewish Studies, University of Manchester, United Kingdom. Co-published by SATIRE, MONOTHEISM AND SCEPTICISM Joshua L. Moss* ABSTRACT: The habits of mind which gave Israel’s ancestors cause to doubt the existence of the pagan deities sometimes lead their descendants to doubt the existence of any personal God, however conceived. Monotheism was and is a powerful form of Scepticism. The Hebrew Bible contains notable satires of Paganism, such as Psalm 115 and Isaiah 44 with their biting mockery of idols. Elijah challenged the worshippers of Ba’al to a demonstration of divine power, using satire. The reader knows that nothing will happen in response to the cries of Baal’s worshippers, and laughs. Yet, the worshippers of Israel’s God must also be aware that their own cries for help often go unanswered. The insight that caused Abraham to smash the idols in his father’s shop also shakes the altar erected by Elijah. Doubt, once unleashed, is not easily contained. Scepticism is a natural part of the Jewish experience. In the middle ages Jews were non-believers and dissenters as far as the dominant religions were concerned. With the advent of modernity, those sceptical habits of mind could be applied to religion generally, including Judaism. -

Hinduism in Time and Space

Introduction: Hinduism in Time and Space Preview as a phenomenon of human culture, hinduism occupies a particular place in time and space. To begin our study of this phenomenon, it is essential to situate it temporally and spatially. We begin by considering how the concept of hinduism arose in the modern era as a way to designate a purportedly coherent system of beliefs and practices. since this initial construction has proven inadequate to the realities of the hindu religious terrain, we adopt “the hindu traditions” as a more satisfactory alternative to "hinduism." The phrase “hindu traditions” calls attention to the great diversity of practices and beliefs that can be described as “hindu.” Those traditions are deeply rooted in history and have flourished almost exclusively on the indian subcontinent within a rich cultural and religious matrix. As strange as it may seem, most Hindus do The Temporal Context not think of themselves as practicing a reli- gion called Hinduism. Only within the last Through most of the millennia of its history, two centuries has it even been possible for the religion we know today as Hinduism has them to think in this way. And although that not been called by that name. The word Hin- possibility now exists, many Hindus—if they duism (or Hindooism, as it was first spelled) even think of themselves as Hindus—do not did not exist until the late eighteenth or early regard “Hinduism” as their “religion.” This irony nineteenth century, when it began to appear relates directly to the history of the concept of sporadically in the discourse of the British Hinduism. -

THE UNITY of GOD Introduction Monotheism, As a Word, Was Coined

CHAPTER SIX THE UNITY OF GOD René Munnik (Tilburg University) Introduction Monotheism, as a word, was coined in early modernity.1 It was meant to indicate religions, theologies or religious philosophies that apprehend God as “the one and only One for all.” The “oneness,” indicated by the prefix monos, had, and has, a triple meaning: it stands for God’s unique- ness—the “one and only, and no other”—, it stands for God’s unity— “One, no dividedness, fickleness or struggles within godself”—, and it stands for God’s universality—“for all, not for some.” Strictly speaking, these meanings do not necessarily imply each other, but orthodox “monotheism” generally holds that God is unique and universal because of God’s unity; whereas the gods being “many,” “particular” and “capricious” within and among themselves. Besides, “monotheism” is a word of controversies, in the sense that it is meant to exclude other ideas about God or the divine. Its natural place is within an arena of contested views, like polytheism, pantheism, deism, henotheism and even poly- demonism; all these words, again, being modern words. Hence, the use and meaning of this word “monotheism” presupposes a modern systematisation or taxonomy of different religious phenom- ena or theological convictions and their mutual antagonisms. It is hard to imagine why a non-Western, non-modern “polytheist” should con- sider himself as such, although he may in fact venerate “many gods.” It is against the background of the conceptual framework of modern 1 Henry More (1614-1687), a prominent member of the Cambridge Platonist School was among the first who used it. -

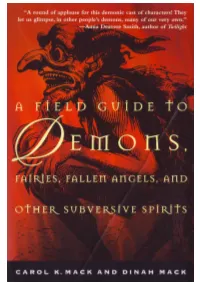

A-Field-Guide-To-Demons-By-Carol-K

A FIELD GUIDE TO DEMONS, FAIRIES, FALLEN ANGELS, AND OTHER SUBVERSIVE SPIRITS A FIELD GUIDE TO DEMONS, FAIRIES, FALLEN ANGELS, AND OTHER SUBVERSIVE SPIRITS CAROL K. MACK AND DINAH MACK AN OWL BOOK HENRY HOLT AND COMPANY NEW YORK Owl Books Henry Holt and Company, LLC Publishers since 1866 175 Fifth Avenue New York, New York 10010 www.henryholt.com An Owl Book® and ® are registered trademarks of Henry Holt and Company, LLC. Copyright © 1998 by Carol K. Mack and Dinah Mack All rights reserved. Distributed in Canada by H. B. Fenn and Company Ltd. Library of Congress-in-Publication Data Mack, Carol K. A field guide to demons, fairies, fallen angels, and other subversive spirits / Carol K. Mack and Dinah Mack—1st Owl books ed. p. cm. "An Owl book." Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8050-6270-0 ISBN-10: 0-8050-6270-X 1. Demonology. 2. Fairies. I. Mack, Dinah. II. Title. BF1531.M26 1998 99-20481 133.4'2—dc21 CIP Henry Holt books are available for special promotions and premiums. For details contact: Director, Special Markets. First published in hardcover in 1998 by Arcade Publishing, Inc., New York First Owl Books Edition 1999 Designed by Sean McDonald Printed in the United States of America 13 15 17 18 16 14 This book is dedicated to Eliza, may she always be surrounded by love, joy and compassion, the demon vanquishers. Willingly I too say, Hail! to the unknown awful powers which transcend the ken of the understanding. And the attraction which this topic has had for me and which induces me to unfold its parts before you is precisely because I think the numberless forms in which this superstition has reappeared in every time and in every people indicates the inextinguish- ableness of wonder in man; betrays his conviction that behind all your explanations is a vast and potent and living Nature, inexhaustible and sublime, which you cannot explain. -

Mircea Eliade

THE SACRED AND THE PROFANE THE NATURE OF RELIGION by Mircea Eliade Translated from the French by Willard R. Trask A Harvest Book Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc. New York CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 8 CHAPTER I Sacred Space and Making the World Sacred 20 CHAPTER I1 Sacred Time and Myths 68 CHAPTER Ill The Sacredness of Nature and Cosmic Religion 116 / CHAPTER IV Human Existence and Sanctified Life 162 CHRONOLOGICAL SURVEY The "History of ReligWus" as a Branch of Knowledge 216 SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY 234 INDEX 244 The extraordinary interest aroused all over the for example; it was not an idea, an abstract notion, a world by Rudolf Otto's Das Heilige (The Sacred), pub- mere moral allegory. It was a terrible power, manifested lished in 1917, still persists. Its success was certainly in the divine wrath. due to the author's new and original point of view. In- In Das Heilige Otto sets himself to discover the char- stead of studying the ideas of God and religion, Otto acteristics of this frightening and irrational experience. undertook to analyze the modalities of the religious, He finds the feeling of terror before the sacred, before experience. Gifted with great psychological subtlety, and the awe-inspiring mystery (mysterium tremendum), the thoroughly prepared by his twofold training as theo- majesty (majestas) that emanates an overwhelming logian and historian of religions, he succeeded in de- superiority of power; he finds religious fear before the termining the content and specific characteristics of fascinating mystery (mysterium fascimms) in which religious experience. Passing over the rational and perfect fullness of being flowers. -

1 UNIT 1 INTRODUCTION to THEISM Contents 1.0 Objectives

UNIT 1 INTRODUCTION TO THEISM Contents 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Types of Theism 1.3 Kinds of Theism 1.4 Let Us Sum Up 1.5 Key Words 1.6 Further Readings and References 1.0 OBJECTIVES Is there a God? God is one or many? Do celestial beings (gods, angels, spirits, and demons) exist? Is there life after death? Is religion a need for modern human? If there is a God then why evil exists? Can man comprehend God? Can the human communicate with God? Does God answer prayers? There are many existential questions raised by humans in the realm of religion, spirituality and metaphysics. Theism is a philosophical ideology which answers the questions arose above in its affirmative. In simple words theism is an ideology that propagates belief in the existence of God or gods. The term ‘theism’ is synonymous to “having belief in God”. In the broadest sense, a theist is a person with the belief that at least one deity (God) exists. This God can be addressed as The Absolute, The Being, Ground of Being, The Ultimate, The World-Soul, the Supreme Good, The Truth, The First Cause, The Supreme Value, The Thing in Itself, The Mystery etc. Theism acknowledges that this god is a living being having personality, will and emotions. Theists believe in a personal God who is the creator and sustainer of life. The answers for the questions ‘Who is god?’ ‘What is god?’ are attempted by the theists. In discussing theism there arises another important question. It is like when was the human mind started to think about God? Many theistic theologians believe that “God consciousness” is innate in the human mind. -

![Sacred and the Profan [258P]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7124/sacred-and-the-profan-258p-2207124.webp)

Sacred and the Profan [258P]

THE SACRED AND THE PROFANE THE NATURE OF RELIGION THE SACRED AND THE PROFANE THE NATURE OF RELIGION by MirceaEltade Translated from the French by Williard R. Trask A Harvest Book Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc. New York Copyright © 1957 by Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag GmbH English translation copyright © 1959 by Harcourt, Inc. Copyright renewed 1987 by Harcourt, Inc. This book was originally translated from the French into German and published in Germany under the title Das Heilige und das Projane. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without pennission in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission to make copies of any part of the work should be submitted online at www.harcourt.com/contact or mailed to: Permissions Department, Harcourt, Inc., 6277 Sea Harbor Drive, Orlando, Florida 32887-6777. www.HarcourtBooks.com ISBN-13: 978-0-15-679201-1 (Pb) ISBN-10: 0-15-679201-X (Pb) Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 58-10904 Printed in the United States of America UU TT SS RR Q_Q_ PP OO NN MM LL CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 8 CHAPTER I Sacred Space and Making the World Sacred 20 CHAPTER II Sacred Time and Myths 68 CHAPTER III The Sacredness of Nature and Cosmic Religion 116 CHAPTER IV Human Existence and Sanctified Life 162 CHRONOLOGICAL SURVEY The "History of religions" as a Branch of Knowledge 216 SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY 234 INDEX INTRODUCTION T h e extraordinary interest aroused all over the world by Rudolf Otto s Das Heilige (The Sacred), pub lished in 1917, still persists. -

The Relevance of Hindu God Concepts and Arguments Proving the Existence of God Perspective Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz

Vol. 4 No. 2 October 2020 THE RELEVANCE OF HINDU GOD CONCEPTS AND ARGUMENTS PROVING THE EXISTENCE OF GOD PERSPECTIVE GOTTFRIED WILHELM LEIBNIZ By: Krisna S. Yogiswari Sekolah Tinggi Agama Hindu Negeri Mpu Kuturan Singaraja Email: [email protected] Received: June 23, 2020 Accepted: October 12, 2020 Published: October 31, 2020 Abstract Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz is a German philosopher who provides a comprehensive argument about the existence of God. Although Leibniz has made a mistake in thinking about God, the evidence of God’s presence offered by him gives us an example and a strength to deepen our faith: Leibniz’s courage is to increase his confidence and his power to maintain God's existence. The arguments presented by Leibniz are very relevant to the concept of God in Hinduism. It also seems that with evidence of harmony that had already been built before, Leibniz fell into the trap of atheism implicitly because it denied the existence of a personal God and only relied on internal law. Regarding the harmony that had already been built before, Leibniz explained that civil laws were working in monade. Monade are predetermined natures, which result in having one characteristic that governs everything. But the best is that not only for the whole in general but also for individuals, especially individuals who have a love for God. Keyword: Leibniz, Existence, God, Hinduism 175 Vol. 4 No.2 October 2020 I. INTRODUCTION qualitative philosophical research approach, The issue and debate about the with the existence of God as a material existence of God is a line of continuity that object and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz’s flows and leads to the entire history of the perspective as a formal object. -

Rosemary Ellen Guiley, Ph.D

The Encyclopedia of ANGELS The Encyclopedia of ANGELS Second Edition Rosemary Ellen Guiley, Ph.D. Foreword by Lisa J. Schwebel, Ph.D. The Encyclopedia of Angels, Second Edition Copyright © 2004 by Visionary Living, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information contact: Facts On File, Inc. 132 West 31st Street New York NY 10001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Guiley, Rosemary. The encyclopedia of angels / Rosemary Ellen Guiley; foreword by Lisa Schwebel.—2nd Ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8160-5023-6 (alk. paper) 1. Angels—Dictionaries. I. Title. BL477.G87 2003 202’.15’03—dc22 2003060147 Facts On File books are available at special discounts when purchased in bulk quantities for businesses, associations, institutions, or sales promotions. Please call our Special Sales Department in New York at (212) 967-8800 or (800) 322–8755. You can find Facts On File on the World Wide Web at http://www.factsonfile.com Text design by Erika K. Arroyo Cover design by Semadar Megged Printed in the United States of America VB FOF 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 This book is printed on acid-free paper. For Lynne Hertsgaard CONTENTS f ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ix FOREWORD xi AUTHOR’S INTRODUCTION TO THE SECOND EDITION xv AUTHOR’S INTRODUCTION TO THE FIRST EDITION xvii ENTRIES A TO Z 1 BIBLIOGRAPHY 380 INDEX 387 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS f My deepest appreciation goes to Joanne P. -

Joseph Smith and the Trinity: an Analysis and Defense of the Social Model of the Godhead

Faith and Philosophy: Journal of the Society of Christian Philosophers Volume 25 Issue 1 Article 3 1-1-2008 Joseph Smith and the Trinity: An Analysis and Defense of the Social Model of the Godhead David Paulsen Brett McDonald Follow this and additional works at: https://place.asburyseminary.edu/faithandphilosophy Recommended Citation Paulsen, David and McDonald, Brett (2008) "Joseph Smith and the Trinity: An Analysis and Defense of the Social Model of the Godhead," Faith and Philosophy: Journal of the Society of Christian Philosophers: Vol. 25 : Iss. 1 , Article 3. DOI: 10.5840/faithphil20082513 Available at: https://place.asburyseminary.edu/faithandphilosophy/vol25/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at ePLACE: preserving, learning, and creative exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faith and Philosophy: Journal of the Society of Christian Philosophers by an authorized editor of ePLACE: preserving, learning, and creative exchange. JOSEPH SMITH AND THE TRINITY: AN ANALYSIS AND DEFENSE OF THE SOCIAL MODEL OF THE GODHEAD David Paulsen and Brett McDonald The theology of Joseph Smith remains controversial and at times divisive in the broader Christian community. This paper takes Smith’s trinitarian theol- ogy as its point of departure and seeks to accomplish four interrelated goals: (1) to provide a general defense of “social trinitarianism” from some of the major objections raised against it; (2) to express what we take to be Smith’s understanding of the Trinity; (3) to analyze the state of modern ST and (4) to argue that, as a form of ST, Smith’s views contribute to the present discussion amongst proponents of ST.