Notes from the Nanaimo Bar Trail

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Food Inventions Across Canada

Food Inventions Across Canada By Cole Wahba Poutine Poutine originated in Quebec. Poutine was invented in Le Roy Did you know that poutine is Jucep in Canada's national food? 1964. Peanut Butter Dr. John Kellogg Peanut butter was Peanut butter was invented in called it protein for used a lot during Montreal during 1884. It was people who can invented by Marcellus Edison WWII because hardly chew. there was a meat shortage. Nanaimo Bar The Nanaimo bar was The bar got popular invented by the when Susan A Nanaimo bar has a wafer, woman at the Mendelson wrote nut and coconut base, a Nanaimo hospital in about it in her custard icing in the centre, the 1950s. cookbook in 1980. and a chocolate ganache top. California Roll This roll was invented in The California roll Vancouver, B.C. contains crab, The California roll was cucumber, avocado, created in 1971. It was rice, and seaweed. invented by chef Tojo. Fun Facts ● Canada’s national drink: Caesar ● Canada’s national food: Poutine ● Canadians buy more ice cream in the winter than in the summer ● Canada produces 70% of the worlds maple syrup, 91% of that is made in Quebec ● Canada grows 90% of the worlds mustard seed, 80% of that is grown in Saskatchewan Sources California roll https://www.insider.com/how-the-california-roll-was-invented-by-a-canadian-chef-2020-8 Nanaimo bar https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/nanaimo-bar#:~:text=Susan%20Mendels on%20is%20perhaps%20most,business%20to%20sell%20the%20dessert. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/nanaimo-bar-controversy-1.5935977 Poutine https://labanquise.com/en/poutine-history.php#:~:text=In%201957%2C%20a%20client%20n amed,Genius!&text=A%20Drummondville%20restaurant%20called%20Le,is%20the%20inve ntor%20of%20poutine. -

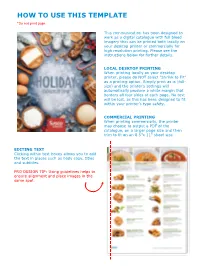

HOW to USE THIS TEMPLATE *Do Not Print Page

HOW TO USE THIS TEMPLATE *Do not print page This communication has been designed to work as a digital catalogue with full bleed imagery that can be printed both locally on your desktop printer or commercially for high resolution printing. Please see the instructions below for further details. LOCAL DESKTOP PRINTING When printing locally on your desktop printer, please do NOT select “Shrink to Fit” as a printing option. Simply print as is (full- size) and the printer’s settings will automatically produce a white margin that borders all four sides of each page. No text will be lost, as this has been designed to fit within your printer’s type safety. COMMERCIAL PRINTING When printing commercially, the printer may choose to output a PDF of the catalogue, on a larger page size and then trim to fit on an 8.5"x 11" sheet size. EDITING TEXT Clicking within text boxes allows you to edit the text in places such as body copy, titles and subtitles. PRO DESIGN TIP: Using guidelines helps to ensure alignment and place images in the same spot. Being together is what matters most and LET’S TOAST TO THE nothing brings people together like food. We have packed this holiday catalogue with unique items and inspiring recipes to help HOLIDAY SEASON! you and your customers celebrate this holiday season! Thank you for choosing us to be your most valued and trusted business partner. We wish you a wonderful holiday season. Sincerely, Sysco Canada 03 05 06 APPETIZERS CHARCUTERIE BREAKFAST BOARD 07 09 11 CENTRE OF CONDIMENTS, SIDE THE PLATE SPICES & STARCHES SAUCES 12 13 17 PRODUCE DESSERTS BEVERAGES 18 19 24 BAKING HOLIDAY RECIPES INGREDIENTS ACCESSORIES 31 32 HEALTHCARE HOLIDAY CONTENTS & SENIOR ACTIVITES LIVING Contact your Sysco Representative for more information. -

Cheri's Bakery Dessert Bar Menu

100 150 200 30 50 75 Price - - - - - - 49 74 99 149 199 299 per Guest Cheri’s Bakery Basic 5 6 7 8 9 10 $2.20 choices choices choices choices choices choices 3 4 5 6 7 8 Basic w/ $1.35 Dessert Bar Menu choices choices choices choices choices choices cake served Classic 5 6 8 10 12 14 $2.75 choices choices choices choices choices choices Basic Cookie Bar 3 4 6 8 10 12 *Classic w/ $1.65 choices choices choices choices choices choices Mini Drop Cookies & cake served Buttercream Buttons Elegant 5 6 8 10 12 14 $3.00 choices choices choices choices choices choices 3 4 6 8 10 12 Classic Elegant w/ $1.90 cake served choices choices choices choices choices choices Mini Drop Cookies, Elaborate 5 6 8 10 12 14 $3.30 Buttercream Buttons, Mini choices choices choices choices choices choices 3 4 6 8 10 12 Cupcakes & Pie Bites Elaborate $2.20 w/ cake choices choices choices choices choices choices Elegant Extravagantserved 5 6 8 10 12 14 $4.65 choices choices choices choices choices choice 3 4 6 8 10 12s Mini Drop Cookies, Extravagant $3.55 Buttercream Buttons, Mini w/ cake choices choices choices choices choices choices Bars, Mini Cupcakes & Pie Bites served DESSERT BAR GUIDELINES – Mini Dessert Only includes 5 pieces per Elaborate guest. Mini Dessert with Cake servings includes 3 pieces per guest. Mini Drop Cookies, Buttercream Buttons, Mini Mini Drop Cookies – Chocolate Chip, Snickerdoodle, Ginger, Lemon Drop, Bars, Mini Cupcakes, Pie Bites Cranberry Orange, Mint Double Chocolate Chip & Drop Sugar & Brownies Buttercream Buttons – Mini Cookies with -

WHOLESALE PRODUCT CATALOG Handcrafted, Custom Desserts

WHOLESALE PRODUCT CATALOG Handcrafted, custom desserts. LET US DO THE BAKING. We are a commercial wholesale bakery, proudly serving the restaurant and retail grocery industry since 1981. We specialize in creating unforgettable desserts for food- focused establishments. Whether you are looking for a custom dessert to reflect the spirit of your restaurant’s menu, or interested in an item from our existing product line, we offer both restaurant-ready and retail-ready dessert creations that make a lasting impression. Table of Contents HANDMADE WITH HEART IN OUR SOUTHERN KITCHEN SINCE 1981. Big Cheesecakes 4 In 1981, Valerie Wilson set out to create the perfect Cheesecakes 8 cheesecake. Armed with an idea and a five-quart mixer in her Nashville-based home kitchen, Valerie devoted many Seasonal 12 hours of careful research and development to perfecting Minis & Individuals 13 her recipe. Nashville restaurants soon began offering Valerie’s cheesecake to their customers, and Tennessee Pies 16 Cheesecake was born. Brownies 17 Handcrafted desserts, quality ingredients, and the utmost Cakes 18 care by our production team: these are the pillars of our Specialty & Bars 20 company, and they have been since our first cheesecake. We are now proudly celebrating more than three decades Retail 21 in business, the recent expansion of our production facility Cookies 21 Valerie Wilson to a 40,000-square-foot space, and an extensive product Founder & President of Tennessee Cheesecake line that ranges from cheesecakes of all flavors and sizes Services & Capabilities 22 to Southern-inspired pies and beyond. Index 23 Visit us at TennesseeCheesecake.com. 2 Making life.. -

Mother Road in Bloomington-Normal

BLOOMINGTON-NORMAL AREA OFFICIAL VISITOR GUIDE Hit the What’s New Mother Places and eateries p. 2 Worth the Trip Road Nearby attractions p. 24 p. 22 RT 66 RUNS THROUGH BN Welcome to BN! We are pleased you are visiting our delightful communities. We have put together the most up-to-date information on our area in this Visitor Guide. This guide includes the activities and entertainment that will enhance your experience while visiting. We are highlighting new attractions, local eateries, our Uptown and Downtown shopping areas, Route 66 nostalgia, and the finest hotels in Central Illinois. The Bloomington-Normal area is a dynamic community home to more than 173,000 people. We are proud to have State Farm Insurance, COUNTRY Financial, Illinois State University, Illinois Wesleyan University, and Rivian Automotive as our major employers. If there is anything our office can do to make your visit more enjoyable, please do not hesitate to contact us. Best Regards, Crystal Howard, President/CEO, Bloomington-Normal Area Convention & Visitors Bureau Crystal Howard Tari Renner Chris Koos President/CEO BNACVB Mayor of Bloomington Mayor of Normal The Visitor Guide is published annually by the BNACVB and is distributed locally and nationally throughout Facebook.com/VisitBN the calendar year. For advertising information or questions about theVisitor Guide, please contact our office. Visit_BN The BNACVB has made every attempt to verify the information contained in this guide and assumes no liability for incorrect or outdated information. The BNACVB is a publicly funded organization and does not @VisitBN evaluate restaurants, attractions, or events listed in this guide with the exception of our Hotel Standards Program. -

Everyday Menu Breakfast Collections Priced Per Guest with a 10 Person Minimum

Everyday Menu Breakfast Collections Priced per guest with a 10 person minimum Basic Beginnings $6.19 Muffins, cream cheese strudels, fruit turnovers and cheese biscuits served with butter and Seattle’s Best organic fair trade coffee and Tazo tea. Continental Breakfast $9.49 Includes muffins, scones, cream cheese strudels, fruit turnovers and cheese biscuits served with butter, fruit preserves, fresh seasonal sliced fruit, Seattle’s Best organic fair trade coffee and Tazo tea. Morning Assortment $13.39 Includes muffins, scones, cream cheese strudels, fruit turnovers and cheese biscuits served with butter, fruit preserves, fresh seasonal sliced fruit, yogurt cups, chilled assorted fruit juices, Seattle’s Best organic fair trade coffee and Tazo tea. Healthy Choice Breakfast $9.69 Choice of wholesome freshly baked fruit and fibre loaf, raspberry yogurt loaf, or caramel coffee cake loaf, served with assorted individual yogurt cups, fresh seasonal sliced fruit and cheese platter, Seattle’s Best organic fair trade coffee and Tazo tea. Hot Breakfast Priced per guest with a 10 person minimum Early Riser Buffet $15.99 Assorted pastries, scrambled eggs, crisp bacon or sausage links, home fried potatoes, fresh seasonal sliced fruit, assorted juices, Seattle’s Best organic fair trade coffee and Tazo tea. Sunrise Breakfast $17.99 Assorted pastries, scrambled eggs, crisp bacon or sausage links, pancakes or French toast, fresh seasonal sliced fruit, home fried potatoes, assorted juices, Seattle’s Best organic fair trade coffee and Tazo tea. Breakfast Sandwich Buffet $13.99 Choice of bacon or sausage breakfast sandwiches on an English muffin with sliced tomato and cheddar cheese. Served with fresh seasonal sliced fruit, home fried potatoes, assorted juices, Seattle’s Best organic fair trade coffee and Tazo tea. -

Breakfast Lunch Alternates PM Alternates Dinner Alternates HS

Week 1 McCormick Home Week at a Glance Regular McCormick Spring/Summer 2019 Monday 1 Tuesday 2 Wednesday 3 Thursday 4 Friday 5 Saturday 6 Sunday 7 Breakfast Oatmeal Cream of Wheat w/Bran Oatmeal Oatmeal Oatmeal Oatmeal Oatmeal Scrambled Eggs Breakfast Sliced Cheese Boiled Egg Scrambled Eggs Poached Egg Scrambled Eggs French Toast WW Toast w/Margarine Raspberry Yogurt Muffin WW Toast w/Margarine Buttered Raisin Toast WW Toast w/Margarine WW Toast w/Margarine Crispy Bacon Banana Banana Banana Banana Banana Banana Maple Syrup Banana Lunch Cream of Celery Soup Chicken & Rice Soup Cream Of Mushroom Soup Tomato Juice Pea w/Ham Soup Crm of Tomato & Red Pepper Soup Vegetable Soup Beef Pot Pie Spinach Quiche Cheese Pizza Hamburger w/Condiments BBQ Pulled Pork Cheese & Onion Sandwich Haddock Bites w/Tartar Sauce Diced Turnip California Mixed Vegetables Caesar Salad Potato Chips Sunrise Mixed Vegetables Cucumber Slices Savoury Diced Potatoes Tiger Mousse Orange Sherbet Cinnamon Roll Lettuce & Tomato Slices Nanaimo Bar Choice of Salad Dressing Tomato Parmesan Vanilla Ice Cream Cup Macaroon Madness Butterscotch Ice Cream Alternates Cheddar Cheese w/Fruit Plate Turkey Salad Sandwich Salmon Salad Sandwich Turkey Mandarin Salad Egg Salad Sandwich Pork & Pineapple Stir Fry Ham & Swiss Sliders WW Dinner Roll Pickled Beets Creamy Cucumber Salad WW Dinner Roll Greek Salad w/Feta Steamed Rice Creamy Coleslaw Citrus Fruit Cup Diced Pears Blueberries Fresh Fruit Diced Watermelon Vegetables Stir Fry Mixed Berries Strawberries PM Assorted Diet Drinks Assorted -

Catering Menu

Our catalog takes you through the overall selection of menus available to choose from, pick the package you like or simply design your entire unique combination of items. Once you are ready to order, the hassle free process begins. Place your order via phone, e-mail or homing pigeon with any queries you may have. We will contact you to confirm you order and details. 745 Baseline Rd, Mesa AZ 85 210 | e-mail: [email protected] Visit us at: www.beaverchoice.com NORDIC FAIR page 3 FINGER FOOD page 5 PIEROGI PARTY page 7 HOT BUFFET page 9 CORPORATE LUNCH page 11 TERMS OF TRADE page 12 To order Call: 480-696 0934 or order on line wwww.beaverchoice.com 745 W. Baseline rd. Mesa AZ Nordic Fair 3 Party Platters Traditional Nordic Party Platters consists of Meat or Seafood, Seasonal Fruits, Vegetables and a Potato Salad. They are delicious and beautifully decorated therefore a feast for your eyes and your belly. BBQ - 10.95 p/p Grilled Chicken, Grilled Ribs, Seasonal Fruits and Vegetables. Seafood - 14.95* Shrimp, Cured Salmon, Asparagus, Green Peas,. Roast Beef and Ham - 12.95 Roast Beef, Ham, Black Olives, Pineapple, Seasonal Fruits and Vegetables. Pork Tenderloin - 13.95 Seared & Baked Pork Tenderloin, Tomatoes, Pineapple, Seasonal Fruits & Vegetables. Party Platter Italian - 12.95 Variety of Italian Cold Cuts including Prosciutto, Olives, Cherry Tomatoes, Peppers and Pasta Salad. Sandwich Cake - Smörgåstårta Smörgåstårta is a Swedish dish and it is exactly as it sounds and looks - a giant sandwich cake which is made up of layers of bread with so much filling that it more resembles a torte than a sandwich. -

Canadian Desserts (Paper).Pdf

Canadian Desserts By Everett “Forget the beaver, forget the glorious maple leaf, forget the haunting loon, for all these years the country has completely overlooked the most important contribution to our identity as a nation, the butter tart. The delicate crust supports the rich and creamy center just as the oceans border our natural resources and the people and the animals that dwell here.” (The Canadian Encyclopedia). There are many different opinions on what Canada’s best most iconic dessert is, and most opinions vary from province to province. The most recognizable desserts have varied from era to era. Many factors have contributed to the identity of Canadian desserts. Canadians love a good dessert which has evolved over time, some desserts are the most popular and each popular dessert has a reason why it's considered Canadian. Today in Canada there is a wide selection of desserts to choose from but the most recommended desserts will change depending on what province you are in. On the east coast the butter tart is the most popular dessert. on the prairies the flapper pie is all the rage but in British Columbia the Nanaimo bar reigns supreme. The Nanaimo bar is Canada’s favorite confection as declared by a readers poll in the national post in 2006. There are many reasons why the Nanaimo bar is so popular; one reason is that it is named after the city of Nanaimo, British Columbia. Another reason is that it has been around for so long and it's kind of grown on people. But the most popular dessert might vary from person to person or some people might believe that butter tarts are better with raisins or they are better without. -

DESSERT MENU Mini and Handheld Desserts Banana Cream Pie Shooters: You’Ll Feel Like a Kid Again

DESSERT MENU Mini and Handheld Desserts Banana Cream Pie Shooters: You’ll feel like a kid again. Bourbon S’mores Pot De Crème: Bourbon-chocolate mousse, grahams, marshmallow Candied Bacon in a Shot Glass: With or w/o Guinness-Chocolate Dipping sauce (GF) NEW Cashew Baklava Cigars: A dainty version of our favorite Greek dessert with cashews Chocolate Covered Strawberries: Elegance at its finest, milk or dark (GF) Crème Brûlé: Individual custards kissed with sugar and fire to make a crunchy top (GF) Coconut Cream Pie Shooters: Served in a shooter glass. Creamy and made like Grandma’s! Derby Pies: A mini version of the Southern classic. Bourbon. Chocolate. Pecans. NEW Flourless Chocolate Tortes: rich, dainty, topped with a raspberry (GLUTEN FREE!) Fruit & Cream Tartlets: Pastry cream, fresh fruit, apricot glaze Guinness Dark Chocolate Shot Glass Cake: With Irish cream frosting Mini Lemon Parfaits: Lemon curd, ladyfingers, whipped cream (GF upon request) Pineapple Upside Down Cake Shooters: Old-school perfection in a shot glass Strawberry-White Chocolate Shooter: White chocolate mousse, lemon cream, berries (GF) Tiramisu Parfaits: Individual parfaits with layers of mascarpone, ladyfingers, & espresso Build Your Own Mini Dessert Bar Mix and match mini desserts, mini cupcakes, and cookies to make a dessert bar with all of your favorite sweets! BROWNIES & BARS Brown Butter Rice Krispy Treats: Our favorite version of the classic Cheesecake Bars: Swirled with Made By Mavis artisan jams! NEW Chocolate-Covered Brown Butter Rice Krispy Pops: with -

All-You-Can-Eat Dessert Bar Lancaster County Favorites Dessert

All-You-Can-Eat Dessert Bar Savor the seasons of Bird-in-Hand by topping off your meal with a homemade Bird-in-Hand dessert. It’s a Grandma Smucker tradition and we proudly offer many of her Pennsylvania Dutch favorites. Plus, throughout the year we offer farm-fresh specialties from our nearby farms and orchards. 5.49 Add the full Dessert Bar to your entree or Soup, Salad and Bread Bar for 4.29. Add the full Dessert Bar to kid’s entree for 1.89. Lancaster County Favorites Homemade Apple Dumpling Served warm and topped with cinnamon sauce Served with milk 4.49 Served a la mode additional 2.89 Whoopie Pie 2.59 Whoopie Pies Puddings & Jello Topped with whipped cream Fruited Jello 2.89 Tapioca 2.95 Homemade Pudding of the Day Ask you server for today’s pudding 2.95 Dessert Features Freshly Baked Pies Grandma Smucker’s Wet-bottom Shoofl y Served warm and topped with whipped cream 3.79 Lemon Meringue 3.89 3.89 Apple Crumb Pie Lemon Sponge Oatmeal Banana Cream 3.89 Homemade Bird-in-Hand Family Restaurant Cherry Crumb 3.89 specialty served with whipped cream 3.95 Coconut Cream 3.89 Peanut Butter 3.89 Coconut Custard 3.89 Served a la mode additional 2.89 Egg Custard 3.89 Fresh Apple Crumb 4.29 Cakes Angel Food 3.69 Oatmeal Pie Boston Cream 3.89 Carrot With buttercream icing 3.89 Healthy Endings Chocolate With peanut butter icing 3.69 Fresh Fruit Cup 4.29 Topped with a dip of sherbet 5.29 Pellman’s Cheesecake 4.29 With topping 4.69 No-sugar-added Apple Pie 3.89 Red Velvet No-sugar-added Cherry Pie 3.89 Our own famous recipe, topped No-sugar-added Pudding 2.95 with buttercream icing 3.79 Sugar-free Jello 2.89 Served a la mode additional 2.89 Ice Cream Handcrafted Artisan Ice Cream Premium Quality • Local Ingredients Experience ice cream at its very best. -

British Colombia

Celebrates Canada 150 – British Colombia Welcome to British Colombia, also known as B.C. British Colombia is Canada’s most westerly province – a mountainous area whose population is mainly clustered in its southwestern corner, Vancouver. British Colombia is Canada’s third largest province after Quebec and Ontario, making up 10% of Canada’s land surface. B.C. is a land of diversity and contrast within small areas. British Colombia has two main regions, “the coast” and “the interior”; these two regions both have numerous contrasts and variations within them. Coastal landscapes, characterized by high, snow-covered mountains, contrast with the broad forested upland of the central interior and the plains of the northeast. Mountains cover most of this westerly province. The Rocky Mountains rise abruptly about 1,000–1,500 m above the foothills of Alberta, and some of their snow- and ice-covered peaks tower more than 3,000 m above sea level. Two other mountain systems lie west of the Rocky Mountain Trench: the Columbia Mountains to the south, and the Cassiar-Omineca Mountains to the north. The Interior Plateau made up of broad and gently rolling uplands, covers central British Columbia. There are wide variations in climate within small areas of British Columbia. The major climate contrast is between the coast and the interior, but there are also significant variations between valleys and uplands, and between the northern and southern parts of the province. Relatively warm air masses from the Pacific Ocean bring mild temperatures to the coast during the winters, while cold water keeps coastal temperatures cool in the summer.