Improving English Language Learners' Idiomatic Competence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The English Language: Did You Know?

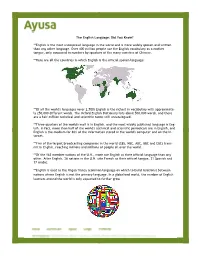

The English Language: Did You Know? **English is the most widespread language in the world and is more widely spoken and written than any other language. Over 400 million people use the English vocabulary as a mother tongue, only surpassed in numbers by speakers of the many varieties of Chinese. **Here are all the countries in which English is the official spoken language: **Of all the world's languages (over 2,700) English is the richest in vocabulary with approximate- ly 250,000 different words. The Oxford English Dictionary lists about 500,000 words, and there are a half-million technical and scientific terms still uncatalogued. **Three-quarters of the world's mail is in English, and the most widely published language is Eng- lish. In fact, more than half of the world's technical and scientific periodicals are in English, and English is the medium for 80% of the information stored in the world's computer and on the In- ternet. **Five of the largest broadcasting companies in the world (CBS, NBC, ABC, BBC and CBC) trans- mit in English, reaching millions and millions of people all over the world. **Of the 163 member nations of the U.N., more use English as their official language than any other. After English, 26 nations in the U.N. cite French as their official tongue, 21 Spanish and 17 Arabic. **English is used as the lingua franca (common language on which to build relations) between nations where English is not the primary language. In a globalized world, the number of English learners around the world is only expected to further grow. -

Etytree: a Graphical and Interactive Etymology Dictionary Based on Wiktionary

Etytree: A Graphical and Interactive Etymology Dictionary Based on Wiktionary Ester Pantaleo Vito Walter Anelli Wikimedia Foundation grantee Politecnico di Bari Italy Italy [email protected] [email protected] Tommaso Di Noia Gilles Sérasset Politecnico di Bari Univ. Grenoble Alpes, CNRS Italy Grenoble INP, LIG, F-38000 Grenoble, France [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT a new method1 that parses Etymology, Derived terms, De- We present etytree (from etymology + family tree): a scendants sections, the namespace for Reconstructed Terms, new on-line multilingual tool to extract and visualize et- and the etymtree template in Wiktionary. ymological relationships between words from the English With etytree, a RDF (Resource Description Framework) Wiktionary. A first version of etytree is available at http: lexical database of etymological relationships collecting all //tools.wmflabs.org/etytree/. the extracted relationships and lexical data attached to lex- With etytree users can search a word and interactively emes has also been released. The database consists of triples explore etymologically related words (ancestors, descendants, or data entities composed of subject-predicate-object where cognates) in many languages using a graphical interface. a possible statement can be (for example) a triple with a lex- The data is synchronised with the English Wiktionary dump eme as subject, a lexeme as object, and\derivesFrom"or\et- at every new release, and can be queried via SPARQL from a ymologicallyEquivalentTo" as predicate. The RDF database Virtuoso endpoint. has been exposed via a SPARQL endpoint and can be queried Etytree is the first graphical etymology dictionary, which at http://etytree-virtuoso.wmflabs.org/sparql. -

Multilingual Ontology Acquisition from Multiple Mrds

Multilingual Ontology Acquisition from Multiple MRDs Eric Nichols♭, Francis Bond♮, Takaaki Tanaka♮, Sanae Fujita♮, Dan Flickinger ♯ ♭ Nara Inst. of Science and Technology ♮ NTT Communication Science Labs ♯ Stanford University Grad. School of Information Science Natural Language ResearchGroup CSLI Nara, Japan Keihanna, Japan Stanford, CA [email protected] {bond,takaaki,sanae}@cslab.kecl.ntt.co.jp [email protected] Abstract words of a language, let alone those words occur- ring in useful patterns (Amano and Kondo, 1999). In this paper, we outline the develop- Therefore it makes sense to also extract data from ment of a system that automatically con- machine readable dictionaries (MRDs). structs ontologies by extracting knowledge There is a great deal of work on the creation from dictionary definition sentences us- of ontologies from machine readable dictionaries ing Robust Minimal Recursion Semantics (a good summary is (Wilkes et al., 1996)), mainly (RMRS). Combining deep and shallow for English. Recently, there has also been inter- parsing resource through the common for- est in Japanese (Tokunaga et al., 2001; Nichols malism of RMRS allows us to extract on- et al., 2005). Most approaches use either a special- tological relations in greater quantity and ized parser or a set of regular expressions tuned quality than possible with any of the meth- to a particular dictionary, often with hundreds of ods independently. Using this method, rules. Agirre et al. (2000) extracted taxonomic we construct ontologies from two differ- relations from a Basque dictionary with high ac- ent Japanese lexicons and one English lex- curacy using Constraint Grammar together with icon. -

(STAAR®) Dictionary Policy

STAAR® State of Texas Assessments of Academic Readiness State of Texas Assessments of Academic Readiness (STAAR®) Dictionary Policy Dictionaries must be available to all students taking: STAAR grades 3–8 reading tests STAAR grades 4 and 7 writing tests, including revising and editing STAAR Spanish grades 3–5 reading tests STAAR Spanish grade 4 writing test, including revising and editing STAAR English I, English II, and English III tests The following types of dictionaries are allowable: standard monolingual dictionaries in English or the language most appropriate for the student dictionary/thesaurus combinations bilingual dictionaries* (word-to-word translations; no definitions or examples) E S L dictionaries* (definition of an English word using simplified English) sign language dictionaries picture dictionary Both paper and electronic dictionaries are permitted. However, electronic dictionaries that provide access to the Internet or have photographic capabilities are NOT allowed. For electronic dictionaries that are hand-held devices, test administrators must ensure that any features that allow note taking or uploading of files have been cleared of their contents both before and after the test administration. While students are working through the tests listed above, they must have access to a dictionary. Students should use the same type of dictionary they routinely use during classroom instruction and classroom testing to the extent allowable. The school may provide dictionaries, or students may bring them from home. Dictionaries may be provided in the language that is most appropriate for the student. However, the dictionary must be commercially produced. Teacher-made or student-made dictionaries are not allowed. The minimum schools need is one dictionary for every five students testing, but the state’s recommendation is one for every three students or, optimally, one for each student. -

Methods in Lexicography and Dictionary Research* Stefan J

Methods in Lexicography and Dictionary Research* Stefan J. Schierholz, Department Germanistik und Komparatistik, Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg, Germany ([email protected]) Abstract: Methods are used in every stage of dictionary-making and in every scientific analysis which is carried out in the field of dictionary research. This article presents some general consid- erations on methods in philosophy of science, gives an overview of many methods used in linguis- tics, in lexicography, dictionary research as well as of the areas these methods are applied in. Keywords: SCIENTIFIC METHODS, LEXICOGRAPHICAL METHODS, THEORY, META- LEXICOGRAPHY, DICTIONARY RESEARCH, PRACTICAL LEXICOGRAPHY, LEXICO- GRAPHICAL PROCESS, SYSTEMATIC DICTIONARY RESEARCH, CRITICAL DICTIONARY RESEARCH, HISTORICAL DICTIONARY RESEARCH, RESEARCH ON DICTIONARY USE Opsomming: Metodes in leksikografie en woordeboeknavorsing. Metodes word gebruik in elke fase van woordeboekmaak en in elke wetenskaplike analise wat in die woor- deboeknavorsingsveld uitgevoer word. In hierdie artikel word algemene oorwegings vir metodes in wetenskapfilosofie voorgelê, 'n oorsig word gegee van baie metodes wat in die taalkunde, leksi- kografie en woordeboeknavorsing gebruik word asook van die areas waarin hierdie metodes toe- gepas word. Sleutelwoorde: WETENSKAPLIKE METODES, LEKSIKOGRAFIESE METODES, TEORIE, METALEKSIKOGRAFIE, WOORDEBOEKNAVORSING, PRAKTIESE LEKSIKOGRAFIE, LEKSI- KOGRAFIESE PROSES, SISTEMATIESE WOORDEBOEKNAVORSING, KRITIESE WOORDE- BOEKNAVORSING, HISTORIESE WOORDEBOEKNAVORSING, NAVORSING OP WOORDE- BOEKGEBRUIK 1. Introduction In dictionary production and in scientific work which is carried out in the field of dictionary research, methods are used to reach certain results. Currently there is no comprehensive and up-to-date documentation of these particular methods in English. The article of Mann and Schierholz published in Lexico- * This article is based on the article from Mann and Schierholz published in Lexicographica 30 (2014). -

Department of English and American Studies English Language And

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Jana Krejčířová Australian English Bachelor’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: PhDr. Kateřina Tomková, Ph. D. 2016 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Author’s signature I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisor PhDr. Kateřina Tomková, Ph.D. for her patience and valuable advice. I would also like to thank my partner Martin Burian and my family for their support and understanding. Table of Contents Abbreviations ........................................................................................................... 6 Introduction .............................................................................................................. 7 1. AUSTRALIA AND ITS HISTORY ................................................................. 10 1.1. Australia before the arrival of the British .................................................... 11 1.1.1. Aboriginal people .............................................................................. 11 1.1.2. First explorers .................................................................................... 14 1.2. Arrival of the British .................................................................................... 14 1.2.1. Convicts ............................................................................................. 15 1.3. Australia in the -

Wiktionary Matcher

Wiktionary Matcher Jan Portisch1;2[0000−0001−5420−0663], Michael Hladik2[0000−0002−2204−3138], and Heiko Paulheim1[0000−0003−4386−8195] 1 Data and Web Science Group, University of Mannheim, Germany fjan, [email protected] 2 SAP SE Product Engineering Financial Services, Walldorf, Germany fjan.portisch, [email protected] Abstract. In this paper, we introduce Wiktionary Matcher, an ontology matching tool that exploits Wiktionary as external background knowl- edge source. Wiktionary is a large lexical knowledge resource that is collaboratively built online. Multiple current language versions of Wik- tionary are merged and used for monolingual ontology matching by ex- ploiting synonymy relations and for multilingual matching by exploiting the translations given in the resource. We show that Wiktionary can be used as external background knowledge source for the task of ontology matching with reasonable matching and runtime performance.3 Keywords: Ontology Matching · Ontology Alignment · External Re- sources · Background Knowledge · Wiktionary 1 Presentation of the System 1.1 State, Purpose, General Statement The Wiktionary Matcher is an element-level, label-based matcher which uses an online lexical resource, namely Wiktionary. The latter is "[a] collaborative project run by the Wikimedia Foundation to produce a free and complete dic- tionary in every language"4. The dictionary is organized similarly to Wikipedia: Everybody can contribute to the project and the content is reviewed in a com- munity process. Compared to WordNet [4], Wiktionary is significantly larger and also available in other languages than English. This matcher uses DBnary [15], an RDF version of Wiktionary that is publicly available5. The DBnary data set makes use of an extended LEMON model [11] to describe the data. -

A Study of Idiom Translation Strategies Between English and Chinese

ISSN 1799-2591 Theory and Practice in Language Studies, Vol. 3, No. 9, pp. 1691-1697, September 2013 © 2013 ACADEMY PUBLISHER Manufactured in Finland. doi:10.4304/tpls.3.9.1691-1697 A Study of Idiom Translation Strategies between English and Chinese Lanchun Wang School of Foreign Languages, Qiongzhou University, Sanya 572022, China Shuo Wang School of Foreign Languages, Qiongzhou University, Sanya 572022, China Abstract—This paper, focusing on idiom translation methods and principles between English and Chinese, with the statement of different idiom definitions and the analysis of idiom characteristics and culture differences, studies the strategies on idiom translation, what kind of method should be used and what kind of principle should be followed as to get better idiom translations. Index Terms— idiom, translation, strategy, principle I. DEFINITIONS OF IDIOMS AND THEIR FUNCTIONS Idiom is a language in the formation of the unique and fixed expressions in the using process. As a language form, idioms has its own characteristic and patterns and used in high frequency whether in written language or oral language because idioms can convey a host of language and cultural information when people chat to each other. In some senses, idioms are the reflection of the environment, life, historical culture of the native speakers and are closely associated with their inner most spirit and feelings. They are commonly used in all types of languages, informal and formal. That is why the extent to which a person familiarizes himself with idioms is a mark of his or her command of language. Both English and Chinese are abundant in idioms. -

German and English Noun Phrases

RICE UNIVERSITY German and English Noun Phrases: A Transformational-Contrastive Approach Ward Keith Barrows A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF 3 1272 00675 0689 Master of Arts Thesis Directors signature: / Houston, Texas April, 1971 Abstract: German and English Noun Phrases: A Transformational-Contrastive Approach, by Ward Keith Barrows The paper presents a contrastive approach to German and English based on the theory of transformational grammar. In the first chapter, contrastive analysis is discussed in the context of foreign language teaching. It is indicated that contrastive analysis in pedagogy is directed toward the identification of sources of interference for students of foreign languages. It is also pointed out that some differences between two languages will prove more troublesome to the student than others. The second chapter presents transformational grammar as a theory of language. Basic assumptions and concepts are discussed, among them the central dichotomy of competence vs performance. Chapter three then present the structure of a grammar written in accordance with these assumptions and concepts. The universal base hypothesis is presented and adopted. An innovation is made in the componential structire of a transformational grammar: a lexical component is created, whereas the lexicon has previously been considered as part of the base. Chapter four presents an illustration of how transformational grammars may be used contrastively. After a base is presented for English and German, lexical components and some transformational rules are contrasted. The final chapter returns to contrastive analysis, but discusses it this time from the point of view of linguistic typology in general. -

New Zealand English

New Zealand English Štajner, Renata Undergraduate thesis / Završni rad 2011 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: Josip Juraj Strossmayer University of Osijek, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences / Sveučilište Josipa Jurja Strossmayera u Osijeku, Filozofski fakultet Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:142:005306 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-09-26 Repository / Repozitorij: FFOS-repository - Repository of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Osijek Sveučilište J.J. Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Preddiplomski studij Engleskog jezika i književnosti i Njemačkog jezika i književnosti Renata Štajner New Zealand English Završni rad Prof. dr. sc. Mario Brdar Osijek, 2011 0 Summary ....................................................................................................................................2 Introduction................................................................................................................................4 1. History and Origin of New Zealand English…………………………………………..5 2. New Zealand English vs. British and American English ………………………….….6 3. New Zealand English vs. Australian English………………………………………….8 4. Distinctive Pronunciation………………………………………………………………9 5. Morphology and Grammar……………………………………………………………11 6. Maori influence……………………………………………………………………….12 6.1.The Maori language……………………………………………………………...12 6.2.Maori Influence on the New Zealand English………………………….………..13 6.3.The -

Introduction to Wordnet: an On-Line Lexical Database

Introduction to WordNet: An On-line Lexical Database George A. Miller, Richard Beckwith, Christiane Fellbaum, Derek Gross, and Katherine Miller (Revised August 1993) WordNet is an on-line lexical reference system whose design is inspired by current psycholinguistic theories of human lexical memory. English nouns, verbs, and adjectives are organized into synonym sets, each representing one underlying lexical concept. Different relations link the synonym sets. Standard alphabetical procedures for organizing lexical information put together words that are spelled alike and scatter words with similar or related meanings haphazardly through the list. Unfortunately, there is no obvious alternative, no other simple way for lexicographers to keep track of what has been done or for readers to ®nd the word they are looking for. But a frequent objection to this solution is that ®nding things on an alphabetical list can be tedious and time-consuming. Many people who would like to refer to a dictionary decide not to bother with it because ®nding the information would interrupt their work and break their train of thought. In this age of computers, however, there is an answer to that complaint. One obvious reason to resort to on-line dictionariesÐlexical databases that can be read by computersÐis that computers can search such alphabetical lists much faster than people can. A dictionary entry can be available as soon as the target word is selected or typed into the keyboard. Moreover, since dictionaries are printed from tapes that are read by computers, it is a relatively simple matter to convert those tapes into the appropriate kind of lexical database. -

English in South Africa: Effective Communication and the Policy Debate

ENGLISH IN SOUTH AFRICA: EFFECTIVE COMMUNICATION AND THE POLICY DEBATE INAUGURAL LECTURE DELIVERED AT RHODES UNIVERSITY on 19 May 1993 by L.S. WRIGHT BA (Hons) (Rhodes), MA (Warwick), DPhil (Oxon) Director Institute for the Study of English in Africa GRAHAMSTOWN RHODES UNIVERSITY 1993 ENGLISH IN SOUTH AFRICA: EFFECTIVE COMMUNICATION AND THE POLICY DEBATE INAUGURAL LECTURE DELIVERED AT RHODES UNIVERSITY on 19 May 1993 by L.S. WRIGHT BA (Hons) (Rhodes), MA (Warwick), DPhil (Oxon) Director Institute for the Study of English in Africa GRAHAMSTOWN RHODES UNIVERSITY 1993 First published in 1993 by Rhodes University Grahamstown South Africa ©PROF LS WRIGHT -1993 Laurence Wright English in South Africa: Effective Communication and the Policy Debate ISBN: 0-620-03155-7 No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo-copying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers. Mr Vice Chancellor, my former teachers, colleagues, ladies and gentlemen: It is a special privilege to be asked to give an inaugural lecture before the University in which my undergraduate days were spent and which holds, as a result, a special place in my affections. At his own "Inaugural Address at Edinburgh" in 1866, Thomas Carlyle observed that "the true University of our days is a Collection of Books".1 This definition - beloved of university library committees worldwide - retains a certain validity even in these days of microfiche and e-mail, but it has never been remotely adequate. John Henry Newman supplied the counterpoise: . no book can convey the special spirit and delicate peculiarities of its subject with that rapidity and certainty which attend on the sympathy of mind with mind, through the eyes, the look, the accent and the manner.