Historic Building Appraisals of the 2 New Items

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Old Town Central - Enrich Visitor’S Experience

C&WDC WG on DC Affairs Paper No. 2/2017 OldOld TTownown CCentralentral 1 Old Town Central - Enrich Visitor’s Experience A contemporary lifestyle destination and a chronicle of how Arts, Heritage, Creativity, and Dining & Entertainment evolved in the city Bounded by Wyndham Street, Caine Road, Possession Street and Queen’s Road Central Possession Street Queen’s Road Central Caine Road Wyndham Street Key Campaign Elements DIY Walking Guide Heritage & Art History Integrated Marketing Local & Overseas Publicity Launch Ceremony City Ambience Tour Products 3 5 Thematic ‘Do-It-Yourself’ Routes For visitors to explore the abundant treasure according to their own interests and pace. Heritage & Dining & Art Treasure Hunt All-in-one History Entertainment Possession Street, Tai Ping Shan PoHo, Upper PMQ, Hollywood Graham market & Best picks Street, Lascar Row, Road, Peel Street, around, LKF, from each Man Mo Temple, StauntonS Street & Aberdeen Street SoHo, Ladder Street, around route Tai Kwun 4 Sample route: All-in-one Walking Tour Route for busy visitors 1. Possession Street (History) 1 6: Gough Street & Kau U Fong (Creative & Design – Designer stores, boutiques 2 4: Man Mo Temple Dining – Local food stalls & (Heritage - Declared International cuisine) 2: POHO - Tai Ping Shan Street (Local Monument ) culture – Temples / Stores/ Restaurant) 6 (Art & Entertainment – Galleries / 4 Street Art/ Café ) 3 7 5 7: Pak Tsz Lane Park 5: PMQ (History) 3: YMCA Bridges Street Centre & ( Heritage - 10: Pottinger Ladder Street Arts & Dining – Galleries, Street -

SAP Crystal Reports

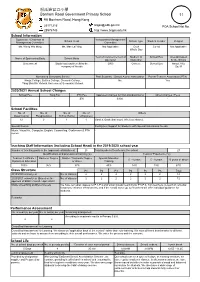

般咸道官立小學 Bonham Road Government Primary School 11 9A Bonham Road, Hong Kong 25171216 [email protected] POA School Net No. 28576743 http://www.brgps.edu.hk School Information Supervisor / Chairman of Incorporated Management School Head School Type Student Gender Religion Management Committee Committee Ms. Wong Wai Ming Ms. Man Lai Ying Not Applicable Gov't Co-ed Not Applicable Whole Day Year of Commencement of Medium of School Bus Area Occupied Name of Sponsoring Body School Motto Operation Instruction by the School Government Study hard and benefit by the 2000 Chinese School Bus About 3765 company of friends Sq. M Nominated Secondary School Past Students' / School Alumni Association Parent-Teacher Association (PTA) King's College, Belilios College, Clementi College, No Yes Tang Shiu Kin Victoria Government Secondary School 2020/2021 Annual School Charges School Fee Tong Fai PTA Fee Approved Charges for Non-standard Items Other Charges / Fees - - $70 $300 - School Facilities No. of No. of No. of No. of Others Classroom(s) Playground(s) School Hall(s) Library(ies) 12 2 1 1 Garden, Basketball court, Wireless intranet. Special Rooms Facility(ies) Support for Students with Special Educational Needs Music, Visual Art, Computer, English, Counselling, Conference & PTA - rooms. Teaching Staff Information (including School Head) in the 2019/2020 school year Number of teaching posts in the approved establishment 25 Total number of teachers in the school 27 Qualifications and professional training (%) Years of Experience (%) Teacher Certificate / Bachelor Degree Master / Doctorate Degree Special Education 0 - 4 years 5 - 9 years 10 years or above Diploma in Education or above Training 100% 96% 33% 40% 14% 19% 67% Class Structure P1 P2 P3 P4 P5 P6 Total 2019/2020 school year No. -

2016 2 Bollettinoeng LOW.Pdf

Growth Architectures Growth is a need that since forever has accompanied mankind and all the phenomena in which it appears. Growth shouldn’t just be acknowledged, but also understood, analyzed and… measured. But how? Measuring growth today has become an obsession that translates into numbers, which are objective and reassuring, but not always able to indicate the real value of a phenomenon. That’s the key issue: value. Growth is not just an inevitable part of human nature, but also a mechanism that can produce value. There are several phenomena in which the need for growth is evident: are we sure that they can all improve our lives? Let’s learn to measure their value ahead of their size. —ak. OPENING REMARKS OPENING REMARKS Growth Architectures The demand for growth is permanent and endless. But, looking towards the future, how much of that growth can be Without continual growth planned and is it possible to build “ growth in an efficient and sustainable and progress, such words as manner? Can individuals and their He who moves not improvement, achievement habitats thrive in an open-source, “ international and sustainable way? forward, goes backward” and success have no meaning” In just one week the world can change. by Simone Bemporad The previous issue of il bollettino ‘The —Goethe —Benjamin Franklin Editor in Chief Place to Be’ reviewed in detail the European Project and its effect on the lives of its citizens. Now, with Brexit in the one hand, the physical environment, into its cities. By 2026, it hopes to move dynamism of the Silicon Valley. -

Hong Kong Guide

HONG KONG GUIDE YOUR FREE HONG KONG GUIDE FROM THE ASIA TRAVEL SPECIALISTS www.asiawebdirect.com Hong Kong is cosmopolitan, exciting and impressive and stands out as a definite ‘must-see’ city. The contrasts of the New Territories to downtown Kowloon could not be starker and even though Hong Kong is a full-on working town its entertainment options are a wonder. Asia's largest shopping hub will present you with a challenge: just how to take all the best retail outlets in on time and the same goes for the fabulous choice of dining. City-wide you'll be amazed at the nightlife options and how the city transforms once the sun sets. Accommodation choices are plentiful. Take enough time to get to know this fascinating destination at your leisure and take in the sights and sounds of one of Asia’s most vibrant cities. WEATHER http://www.hong-kong-hotels.ws/general-info.htm Hong Kong can be considered a year-round destination with a mild climate from the middle of September to February, and warm and humid weather from May to mid-September. SIM CARDS AND DIALING PREFIXES It’s cool and dry in the winter (December to March), and hot, humid and rainy from spring and summer; July records the highest average Prepaid SIM cards are available at cell phone shops and most temperature. Autumn is warm, sunny, and dry. Hong Kong occasionally convenience stores (7-Elevens and Circle K are everywhere). The big experiences severe rainstorms, or typhoons. It rains a lot between May mobile phone service providers here include CSL, PCCW, Three (3) and SmarTone. -

French Firms in Macau -.:: GEOCITIES.Ws

TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIRMS: BREAKDOWN BY SECTORS 3 LIST OF FIRMS BY ALPHABETICAL ORDER 9 LIST OF FIRMS BY PARENT COMPANY 89 LIST OF FIRMS BY PARENT COMPANY 95 French Firms in Hong Kong and Macau - 1999 Edition LIST OF FIRMS: BREAKDOWN BY SECTORS Advertising EURO RSCG PARTNERSHIP Beverages, wines & spirits FIRST VISION LTD. ADET SEWARD FLEXICOM BELCOMBE CO. LTD. FRENCH FASHION LTD CALDBECKS LTD. IMAGE SOLUTIONS CASELLA FAR EAST LIMITED MERCURY PUBLICITY (HK) LTD. CHATEAU DE LA TOUR (ASIA) LTD. SPICY CREATION HK LTD. CHEVAL QUANCARD ASIA LTD CREACTION INTERNATIONAL LTD. CULINA (H.K.) LIMITED Aeronautics DUISDALE LTD. AIRBUS INDUSTRIE-MACAO EURO LUXE (HONG KONG) LTD. DASSAULT FALCON JET CORP FICOFI (INTERNATIONAL) LTD. ELTRA AERONAUTICS FIMOXY CO LTD. METROJET LTD. GRANDS CRUS DE FRANCE LTD. / FRENCH WINE J.L.C. & MOUEIX FAR EAST LTD. JEAN PHILIPPE INTERNATIONAL (HK) LTD Agriculture - Foodstuffs MARTELL FAR EAST TRADING LTD. MEGAREVE AMOY FOOD LTD. MOET HENNESSY ASIA PACIFIC ASIATIQUE EUROPEENNE DE COMMERCE LTD. OLIVIER ASIA LTD. BALA FAR EAST LIMITED OLIVIER HONG KONG LTD. CULINA (H.K.) LIMITEDDELIFRANCE (HK) LTD. PR ASIA DANONE REMY CHINA & HK LTD. EURO LUXE (HONG KONG) LTD. REMY PACIFIQUE LTD. FARGO SERVICES (H.K.) LTD. RICHE MONDE LTD. GRANDS CRUS DE FRANCE LTD. / FRENCH WINE SAVEURS INTERNATIONAL LIMITED INNOLEDGE INTERNATIONAL LTD. SINO-FRENCH RESOURCES LTD. INTERNATIONAL COMMERCIAL AGENCIES SOPEXA LTD. LA ROSE NOIRE TAHLEIA LTD. LESAFFRE (FAR EAST) LTD. LVMH ASIA PACIFIC LTD. OLIVIER ASIA LTD. OLIVIER HONG KONG LTD. Building construction SOPEXA LTD. BACHY SOLETANCHE GROUP TAHLEIA LTD. BOUYGUES DRAGAGES ASIA VALRHONA FAR EAST BYME ENGINEERING (HK) LTD CAMPENON BERNARD SGE DEXTRA PACIFIC LTD. -

Recommended District Council Constituency Areas

District : Central and Western Recommended District Council Constituency Areas +/- % of Population Estimated Quota Code Recommended Name Boundary Description Major Estates/Areas Population (17,282) A01 Chung Wan 18,529 +7.22 N District Boundary 1. HOLLYWOOD TERRACE NE District Boundary E District Boundary SE Monmouth Path, Kennedy Road S Kennedy Road, Macdonnell Road Garden Road, Lower Albert Road SW Lower Albert Road, Wyndham Street Arbuthnot Road, Chancery Lane Old Bailey Street, Elgin Street Peel Street, Staunton Street W Staunton Street, Aberdeen Street Hollywood Road, Ladder Street Queen's Road Central, Cleverly Street Connaught Road Central NW Chung Kong Road A1 District : Central and Western Recommended District Council Constituency Areas +/- % of Population Estimated Quota Code Recommended Name Boundary Description Major Estates/Areas Population (17,282) A02 Mid Levels East 20,337 +17.68 N Chancery Lane 1. PINE COURT 2. ROBINSON HEIGHTS Arbuthnot Road, Wyndham Street 3. THE GRAND PANORAMA NE Wyndham Street, Lower Albert Road 4. TYCOON COURT E Lower Albert Road, Garden Road SE Garden Road S Garden Road, Robinson Road, Old Peak Road Hornsey Road SW Hornsey Road W Hornsey Road, Conduit Road, Robinson Road Seymour Road, Castle Road NW Castle Road, Caine Road, Chancery Lane Elgin Street, Old Bailey Street, Seymour Road Shing Wong Street, Staunton Street A2 District : Central and Western Recommended District Council Constituency Areas +/- % of Population Estimated Quota Code Recommended Name Boundary Description Major Estates/Areas Population -

Chapter One Introduction Chapter Two the 1920S, People and Weather

Notes Chapter One Introduction 1. Steve Tsang, ed., Government and Politics (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 1995); David Faure, ed., Society (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 1997); David Faure and Lee Pui-tak, eds., Economy (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2004); and David Faure, Colonialism and the Hong Kong Mentality (Hong Kong: Centre of Asian Studies, University of Hong Kong, 2003). 2. Cindy Yik-yi Chu, The Maryknoll Sisters in Hong Kong, 1921–1969: In Love with the Chinese (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004), book jacket. Chapter Two The 1920s, People and Weather 1. R. L. Jarman, ed., Hong Kong Annual Administration Reports 1841–1941, Archive ed., Vol. 4: 1920–1930 (Farnham Common, 1996), p. 26. 2. Ibid., p. 27. 3. S. G. Davis, Hong Kong in Its Geographical Setting (London: Collins, 1949), p. 215. 4. Vicariatus Apostolicus Hongkong, Prospectus Generalis Operis Missionalis; Status Animarum, Folder 2, Box 10: Reports, Statistics and Related Correspondence (1969), Accumulative and Comparative Statistics (1842–1963), Section I, Hong Kong Catholic Diocesan Archives, Hong Kong. 5. Unless otherwise stated, quotations in this chapter are from Folders 1–5, Box 32 (Kowloon Diaries), Diaries, Maryknoll Mission Archives, Maryknoll, New York. 6. Cindy Yik-yi Chu, The Maryknoll Sisters in Hong Kong, 1921–1969: In Love with the Chinese (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004), pp. 21, 28, 48 (Table 3.2). 210 / notes 7. Ibid., p. 163 (Appendix I: Statistics on Maryknoll Sisters Who Were in Hong Kong from 1921 to 2004). 8. Jean-Paul Wiest, Maryknoll in China: A History, 1918–1955 (Armonk: M.E. -

Consultancy Agreement No. NEX/1023 West Island Line Environmental Impact Assessment Final Environmental Impact Assessment Report

Consultancy Agreement No. NEX/1023 West Island Line Environmental Impact Assessment Final Environmental Impact Assessment Report TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................................................... 1 2 PROJECT BACKGROUND........................................................................................................................ 1 3 STUDY SCOPE........................................................................................................................................... 1 4 CULTURAL HERITGE RESOURCES ........................................................................................................ 2 5 CONCLUSIONS........................................................................................................................................ 28 FIGURES Figure 6.1 Identified Cultural Heritage Resources Key Plan Figure 6.2 Locations of Identified Cultural Heritage Resources Figure 6.3 Locations of Identified Cultural Heritage Resources Figure 6.4 Locations of Identified Cultural Heritage Resources Figure 6.5 Locations of Identified Cultural Heritage Resources Figure 6.6 Locations of Identified Cultural Heritage Resources Figure 6.7 Locations of Identified Cultural Heritage Resources Figure 6.8 Locations of Identified Cultural Heritage Resources Figure 6.9 Locations of Identified Cultural Heritage Resources Figure 6.10 Locations of Identified Cultural Heritage Resources Figure 6.11 Locations of Identified Cultural -

Historic Building Appraisal 1 Tsang Tai Uk Sha Tin, N.T

Historic Building Appraisal 1 Tsang Tai Uk Sha Tin, N.T. Tsang Tai Uk (曾大屋, literally the Big Mansion of the Tsang Family) is also Historical called Shan Ha Wai (山廈圍, literally, Walled Village at the Foothill). Its Interest construction was started in 1847 and completed in 1867. Measuring 45 metres by 137 metres, it was built by Tsang Koon-man (曾貫萬, 1808-1894), nicknamed Tsang Sam-li (曾三利), who was a Hakka (客家) originated from Wuhua (五華) of Guangdong (廣東) province which was famous for producing masons. He came to Hong Kong from Wuhua working as a quarryman at the age of 16 in Cha Kwo Ling (茶果嶺) and Shaukiwan (筲箕灣). He set up his quarry business in Shaukiwan having his shop called Sam Lee Quarry (三利石行). Due to the large demand for building stone when Hong Kong was developed as a city since it became a ceded territory of Britain in 1841, he made huge profit. He bought land in Sha Tin from the Tsangs and built the village. The completed village accommodated around 100 residential units for his family and descendents. It was a shelter of some 500 refugees during the Second World War and the name of Tsang Tai Uk has since been adopted. The sizable and huge fortified village is a typical Hakka three-hall-four-row Architectural (三堂四横) walled village. It is in a Qing (清) vernacular design having a Merit symmetrical layout with the main entrance, entrance hall, middle hall and main hall at the central axis. Two other entrances are to either side of the front wall. -

Annual Report 2021 Report 2021 年報 年 報 Contents

ANNUAL ANNUAL REPORT 2021 ANNUAL REPORT REPORT 2021 年報 年 報 CONTENTS 2 Corporate Information 3 Financial Review 7 Chairman’s Statement 10 Management Discussion and Analysis 15 Corporate Governance Report 25 Environmental, Social and Governance Report 41 Directors’ Report 56 Independent Auditor’s Report 63 Consolidated Statement of Profit or Loss 64 Consolidated Statement of Profit or Loss and Other Comprehensive Income 65 Consolidated Statement of Financial Position 67 Consolidated Statement of Changes in Equity 68 Consolidated Statement of Cash Flows 71 Notes to the Consolidated Financial Statements 168 Financial Summary 169 Schedule of Major Properties held by the Group Corporate Information 02 BOARD OF DIRECTORS REGISTERED OFFICE Executive Directors: Clarendon House Chung Cho Yee, Mico (Chairman) 2 Church Street CSI Properties Limited Kan Sze Man Hamilton HM 11 Chow Hou Man Bermuda Fong Man Bun, Jimmy Ho Lok Fai Leung King Yin, Kevin HONG KONG HEAD OFFICE AND PRINCIPAL PLACE OF BUSINESS Independent Non-Executive Directors: Lam Lee G. 31/F Cheng Yuk Wo Bank of America Tower Shek Lai Him, Abraham, GBS, JP 12 Harcourt Road Lo Wing Yan, William, JP Central, Hong Kong AUDIT COMMITTEE SHANGHAI OFFICE Cheng Yuk Wo (Chairman) Room 804, The Platinum Lam Lee G. 233 Taicang Road Shek Lai Him, Abraham, GBS, JP Huangpu District Lo Wing Yan, William, JP Shanghai, 200020, China REMUNERATION COMMITTEE AUDITORS Cheng Yuk Wo (Chairman) Chung Cho Yee, Mico Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Lam Lee G. Registered Public Interest Entity Auditors 35/F., One Pacific Place NOMINATION COMMITTEE 88 Queensway Chung Cho Yee, Mico (Chairman) Hong Kong Lam Lee G. -

Food and Environmental Hygiene Department Anti-Mosquito Campaign 2020 (Phase III) in Central & Western District

Circulation Paper C&W BEHWC Paper No.62/2020 Food and Environmental Hygiene Department Anti-mosquito Campaign 2020 (Phase III) in Central & Western District Purpose To brief Members on the arrangements and details for the Anti-mosquito Campaign 2020 (Phase III) to be launched by the Food and Environmental Hygiene Department (FEHD) in Central & Western District. Background 2. The Anti-mosquito Campaign 2020 (Phase II) organized by FEHD was launched between 20.4.2020 and 19.6.2020. Actions taken in the district and the results are detailed at Annex I. 3. In 2019, there were 1 local and 197 imported dengue fever cases; 11 imported chikungunya fever cases; 1 local and 2 imported Japanese encephalitis cases in Hong Kong. No Zika virus infection case were reported. 4. Dengue fever (DF) is an important mosquito-borne disease with public health concern worldwide, especially in the tropics and sub-tropics. The dengue viruses encompass four different serotypes. Dengue infection has a wide spectrum of clinical manifestations and outcomes. The disease is usually mild and self-limiting, but subsequent infections with other serotypes of dengue virus are more likely to result in severe dengue, which can be fatal. DF is not directly transmitted from person to person. It is transmitted to humans through the bites of infective female Aedes mosquitoes. Patients with DF are infective to mosquitoes during the febrile period. When a patient suffering from DF is bitten by a vector mosquito, the mosquito is infected and it may spread the disease by biting other people. DF can spread rapidly in - 1 - densely populated areas that are infested with the vectors Aedes aegypti or Aedes albopictus. -

District: Central & Western

District : Central and Western Proposed District Council Constituency Areas +/- % of Population Projected Quota Code Proposed Name Boundary Description Major Estates/Areas Population (16 599) A01 Chung Wan 13 351 -19.57 N District Boundary 1. HOLLYWOOD TERRACE NE District Boundary E District Boundary SE Kennedy Road, Monmouth Path S Garden Road, Kennedy Road Lower Albert Road, Macdonnell Road SW Arbuthnot Road, Chancery Lane Elgin Street, Lower Albert Road Old Bailey Street, Peel Street Staunton Street, Wyndham Street W Aberdeen Street, Cleverly Street Connaught Road Central, Hollywood Road Ladder Street, Queen's Road Central Staunton Street NW Chung Kong Road A 1 District : Central and Western Proposed District Council Constituency Areas +/- % of Population Projected Quota Code Proposed Name Boundary Description Major Estates/Areas Population (16 599) A02 Mid Levels East 16 508 -0.55 N Arbuthnot Road, Chancery Lane 1. PINE COURT 2. ROBINSON HEIGHTS Elgin Street, Old Bailey Street 3. THE GRAND PANORAMA Wyndham Street 4. TYCOON COURT NE Lower Albert Road, Wyndham Street E Garden Road, Lower Albert Road SE Garden Road S Garden Road, Hornsey Road, Old Peak Road Robinson Road SW Hornsey Road W Castle Road, Conduit Road, Hornsey Road Robinson Road, Seymour Road NW Aberdeen Street, Caine Road, Castle Road Elgin Street, Peel Street, Seymour Road Staunton Street A 2 District : Central and Western Proposed District Council Constituency Areas +/- % of Population Projected Quota Code Proposed Name Boundary Description Major Estates/Areas Population (16 599) A03 Castle Road 20 397 +22.88 N Bonham Road, Breezy Path, Caine Road 1. 39 CONDUIT ROAD 2. BLESSINGS GARDEN Park Road 3.