Final Report of the Commission of Inquiry Into the Rainstorm Disasters 1972

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Global Offering

Innovent Biologics, Inc. 信達生物製藥 Innovent Biologics, Inc. (Incorporated in the Cayman Islands with Limited Liability) Stock Code: 1801 GLOBAL OFFERING JOINT SPONSORS, JOINT GLOBAL COORDINATORS, JOINT BOOKRUNNERS AND JOINT LEAD MANAGERS JOINT GLOBAL COORDINATOR, JOINT BOOKRUNNER AND JOINT LEAD MANAGER JOINT BOOKRUNNER AND JOINT LEAD MANAGER IMPORTANT If you are in any doubt about any of the contents of this prospectus, you should obtain independent professional advice. 信達生物製藥 Innovent Biologics, Inc. (Incorporated in the Cayman Islands with Limited Liability) GLOBAL OFFERING Number of Offer Shares under : 236,350,000 Shares (subject to the the Global Offering Over-allotment Option) Number of Hong Kong Offer Shares : 23,635,000 Shares (subject to reallocation) Number of International Offering Shares : 212,715,000 Shares (subject to reallocation and the Over-allotment Option) Maximum Offer Price : HK$14.00 per Offer Share plus brokerage of 1%, SFC transaction levy of 0.0027% and the Stock Exchange trading fee of 0.005% (payable in full on application in Hong Kong dollars subject to refund) Nominal value : US$0.00001 per Share Stock code : 1801 Joint Sponsors, Joint Global Coordinators, Joint Bookrunners and Joint Lead Managers Joint Global Coordinator, Joint Bookrunner and Joint Lead Manager Joint Bookrunner and Joint Lead Manager Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited, The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited and Hong Kong Securities Clearing Company Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this prospectus, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this prospectus. -

District : Kowloon City

District : Yau Tsim Mong Provisional District Council Constituency Areas +/- % of Population Estimated Quota Code Proposed Name Boundary Description Major Estates/Areas Population (16,964) E01 Tsim Sha Tsui West 20,881 +23.09 N Hoi Fai Road 1. SORRENTO 2. THE ARCH NE Hoi Fai Road, Hoi Po Road, Jordan Road 3. THE CULLINAN E Jordan Road, Canton Road 4. THE HARBOURSIDE 5. THE WATERFRONT Kowloon Park Drive SE Salisbury Road, Avenue of Stars District Boundary S District Boundary SW District Boundary W District Boundary NW District Boundary E02 Jordan South 18,327 +8.03 N Jordan Road 1. CARMEN'S GARDEN 2. FORTUNE TERRACE NE Jordan Road, Cox's Road 3. HONG YUEN COURT E Cox's Road, Austin Road, Nathan Road 4. PAK ON BUILDING 5. THE VICTORIA TOWERS SE Nathan Road 6. WAI ON BUILDING S Salisbury Road SW Kowloon Park Drive W Kowloon Park Drive, Canton Road NW Canton Road, Jordan Road E 1 District : Yau Tsim Mong Provisional District Council Constituency Areas +/- % of Population Estimated Quota Code Proposed Name Boundary Description Major Estates/Areas Population (16,964) E03 Jordan West 14,818 -12.65 N West Kowloon Highway, Hoi Wang Road 1. MAN CHEONG BUILDING 2. MAN FAI BUILDING NE Hoi Wang Road, Yan Cheung Road 3. MAN KING BUILDING Kansu Street 4. MAN WAH BUILDING 5. MAN WAI BUILDING E Kansu Street, Battery Street 6. MAN YING BUILDING SE Battery Street, Jordan Road 7. MAN YIU BUILDING 8. MAN YUEN BUILDING S Jordan Road 9. WAI CHING COURT SW Jordan Road, Hoi Po Road, Seawall W Seawall NW West Kowloon Highway, Hoi Po Road Seawall E 2 District : Yau Tsim Mong Provisional District Council Constituency Areas +/- % of Population Estimated Quota Code Proposed Name Boundary Description Major Estates/Areas Population (16,964) E04 Yau Ma Tei South 19,918 +17.41 N Lai Cheung Road, Hoi Ting Road 1. -

APRES Moi LE DELUGE"? JUDICIAL Review in HONG KONG SINCE BRITAIN RELINQUISHED SOVEREIGNTY

"APRES MoI LE DELUGE"? JUDICIAL REvIEw IN HONG KONG SINCE BRITAIN RELINQUISHED SOVEREIGNTY Tahirih V. Lee* INTRODUCTION One of the burning questions stemming from China's promise that the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) would enjoy a "high degree of autonomy" is whether the HKSAR's courts would have the authority to review issues of constitutional magnitude and, if so, whether their decisions on these issues would stand free of interference by the People's Republic of China (PRC). The Sino-British Joint Declaration of 1984 promulgated in PRC law and international law a guaranty that implied a positive answer to this question: "the judicial system previously practised in Hong Kong shall be maintained except for those changes consequent upon the vesting in the courts of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the power of final adjudication."' The PRC further promised in the Joint Declaration that the "Uludicial power" that was to "be vested in the courts" of the SAR was to be exercised "independently and free from any interference."2 The only limit upon the discretion of judicial decisions mentioned in the Joint Declaration was "the laws of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region and [to a lesser extent] precedents in other common law jurisdictions."3 Despite these promises, however, most of the academic and popular discussion about Hong Kong's judiciary in the United States, and much of it in Hong Kong, during the several years leading up to the reversion to Chinese sovereignty, revolved around a fear about its decline after the reversion.4 The * Associate Professor of Law, Florida State University College of Law. -

SAP Crystal Reports

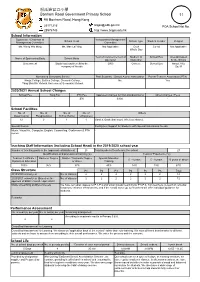

般咸道官立小學 Bonham Road Government Primary School 11 9A Bonham Road, Hong Kong 25171216 [email protected] POA School Net No. 28576743 http://www.brgps.edu.hk School Information Supervisor / Chairman of Incorporated Management School Head School Type Student Gender Religion Management Committee Committee Ms. Wong Wai Ming Ms. Man Lai Ying Not Applicable Gov't Co-ed Not Applicable Whole Day Year of Commencement of Medium of School Bus Area Occupied Name of Sponsoring Body School Motto Operation Instruction by the School Government Study hard and benefit by the 2000 Chinese School Bus About 3765 company of friends Sq. M Nominated Secondary School Past Students' / School Alumni Association Parent-Teacher Association (PTA) King's College, Belilios College, Clementi College, No Yes Tang Shiu Kin Victoria Government Secondary School 2020/2021 Annual School Charges School Fee Tong Fai PTA Fee Approved Charges for Non-standard Items Other Charges / Fees - - $70 $300 - School Facilities No. of No. of No. of No. of Others Classroom(s) Playground(s) School Hall(s) Library(ies) 12 2 1 1 Garden, Basketball court, Wireless intranet. Special Rooms Facility(ies) Support for Students with Special Educational Needs Music, Visual Art, Computer, English, Counselling, Conference & PTA - rooms. Teaching Staff Information (including School Head) in the 2019/2020 school year Number of teaching posts in the approved establishment 25 Total number of teachers in the school 27 Qualifications and professional training (%) Years of Experience (%) Teacher Certificate / Bachelor Degree Master / Doctorate Degree Special Education 0 - 4 years 5 - 9 years 10 years or above Diploma in Education or above Training 100% 96% 33% 40% 14% 19% 67% Class Structure P1 P2 P3 P4 P5 P6 Total 2019/2020 school year No. -

Islands District Council Traffic and Transport Committee Paper T&TC

Islands District Council Traffic and Transport Committee Paper T&TC 41/2020 2020 Hong Kong Cyclothon 1. Objectives 1.1 The 2020 Hong Kong Cyclothon, organised by the Hong Kong Tourism Board, is scheduled to be held on 15 November 2020. This document outlines to the Islands District Council Traffic and Transport Committee the event information and traffic arrangements for 2020 Hong Kong Cyclothon, with the aim to obtain the District Council’s continuous support. 2. Event Background 2.1. Hong Kong Tourism Board (HKTB) is tasked to market and promote Hong Kong as a travel destination worldwide and to enhance visitors' experience in Hong Kong, by hosting different mega events. 2.2. The Hong Kong Cyclothon was debuted in 2015 in the theme of “Sports for All” and “Exercise for a Good Cause”. Over the past years, the event attracted more than 20,000 local and overseas cyclists to participate in various cycling programmes, as well as professional cyclists from around the world to compete in the International Criterium Race, which was sanctioned by the Union Cycliste Internationale (UCI) and The Cycling Association of Hong Kong, China Limited (CAHK). The 50km Ride is the first cycling activity which covers “Three Tunnels and Three Bridges (Tsing Ma Bridge, Ting Kau Bridge, Stonecutters Bridge, Cheung Tsing Tunnel, Nam Wan Tunnel, Eagle’s Nest Tunnel)” in the route. 2.3. Besides, all the entry fees from the CEO Charity and Celebrity Ride and Family Fun Ride and partial amount of the entry fee from other rides/ races will be donated to the beneficiaries of the event. -

Police Report Rooms Receiving 992 Emergency SMS Service Applications S/N Region Report Room Address of Report Room 1

Police Report Rooms receiving 992 Emergency SMS Service Applications S/N Region Report Room Address of Report Room 1. Central District No.2 Chung Kong Road, Sheung Wan, Hong Kong 2. Peak Sub-Division No.92 Peak Road, Hong Kong 3. Western Division No.280 Des Voeux Road West, Hong Kong 4. Aberdeen Division No.4 Wong Chuk Hang Road , Hong Kong Hong Kong 5. Stanley Sub-Division No.77 Stanley Village Road, Stanley, Hong Kong Island 6. Wan Chai Division No. 1 Arsenal Street, Wanchai, Hong Kong 7. Happy Valley Division No.60 Sing Woo Road, Happy Valley, Hong Kong 8. North Point Division No.343 Java Road, Hong Kong 9. Chai Wan Division No.6 Lok Man Road, Chai Wan , Hong Kong 10. Tsim Sha Tsui Division No.213 Nathan Road, Kowloon 11. Yau Ma Tei Division No.3 Yau Cheung Road, Yau Ma Tei, Kowloon 12. Sham Shui Po Division No. 37A Yen chow Street, Kowloon Kowloon 13. Cheung Sha Wan Division No. 880 Lai Chi Kok Road, Kowloon West 14. Mong Kok District No. 142 Prince Edward Road West, Kowloon 15. Kowloon City Division No. 202 Argyle Street, Kowloon 16. Hung Hom Division No.99 Princess Margaret Road, Kowloon 17. Wong Tai Sin District No.2 Shatin Pass Road, Wong Tai Sin, Kowloon 18. Sai Kung Division No.1 Po Tung Road, Sai Kung, Kowloon 19. Kowloon Kwun Tong District No.9 Lei Yue Mun Road, Kwun Tong, Kowloon 20. East Tseung Kwan O District No.110 Po Lam Road North, Tseung Kwan O, Kowloon 21. -

2016 2 Bollettinoeng LOW.Pdf

Growth Architectures Growth is a need that since forever has accompanied mankind and all the phenomena in which it appears. Growth shouldn’t just be acknowledged, but also understood, analyzed and… measured. But how? Measuring growth today has become an obsession that translates into numbers, which are objective and reassuring, but not always able to indicate the real value of a phenomenon. That’s the key issue: value. Growth is not just an inevitable part of human nature, but also a mechanism that can produce value. There are several phenomena in which the need for growth is evident: are we sure that they can all improve our lives? Let’s learn to measure their value ahead of their size. —ak. OPENING REMARKS OPENING REMARKS Growth Architectures The demand for growth is permanent and endless. But, looking towards the future, how much of that growth can be Without continual growth planned and is it possible to build “ growth in an efficient and sustainable and progress, such words as manner? Can individuals and their He who moves not improvement, achievement habitats thrive in an open-source, “ international and sustainable way? forward, goes backward” and success have no meaning” In just one week the world can change. by Simone Bemporad The previous issue of il bollettino ‘The —Goethe —Benjamin Franklin Editor in Chief Place to Be’ reviewed in detail the European Project and its effect on the lives of its citizens. Now, with Brexit in the one hand, the physical environment, into its cities. By 2026, it hopes to move dynamism of the Silicon Valley. -

Agreement No. TD 50/2007 Traffic Study for Mid-Levels Area

Agreement No. TD 50/2007 Traffic Study for Mid-Levels Area Executive Summary 半山區發展限制範圍 研究範圍 August 2010 Agreement No. TD 50/2007 Executive Summary Traffic Study for Mid-Levels Area TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 1. INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Background 1 1.2 Study Objectives 2 1.3 Study Approach and Process 3 1.4 Structure of this Executive Summary 3 2. EXISTING TRAFFIC CONDITIONS 4 2.1 Review of Available Transport Data 4 2.2 Supplementary Traffic Surveys 4 2.3 Existing Traffic Situation 5 3. REDEVELOPMENT POTENTIAL IN MID-LEVELS 8 3.1 Identification of Potential Redevelopment Sites 8 3.2 Maximum Permissible GFA of the Potential Redevelopment Sites 9 3.3 Establishment of Redevelopment Scenarios 10 4. TRAFFIC IMPACT ASSESSMENTS 13 4.1 Transport Model Development 13 4.2 Redevelopment Traffic Generation 14 4.3 Junction Performance Assessments 15 4.4 Effects of West Island Line 17 5. TRAFFIC IMPROVEMENT PROPOSALS 18 5.1 Overview 18 5.2 Proposed Improvement Measures 18 5.3 Measures Considered But Not Pursued 20 6. REVIEW OF THE MID-LEVELS MORATORIUM 22 6.1 Overview 22 6.2 Lifting the MM 22 6.3 Strengthening the MM 23 6.4 Alternative Means of Planning Control 23 6.5 Retaining the MM 24 7. CONCLUSION 25 7.1 Recommendations 25 7.2 Way Forward 26 LIST OF TABLES Page Table 2.1 Summary of Surveys Undertaken 4 Table 2.2 Comparison of Key Demographic and General Traffic Characteristics in Mid-Levels, Happy Valley and Braemar Hill 6/7 Table 3.1 Potential Redevelopment Sites by Type of Lease and Land Use Zoning 8 Table 3.2 Maximum Permissible GFA of the Potential Redevelopment Sites 9 Table 3.3 Summary of Redevelopment Scenarios 10 i Agreement No. -

Urban Forms and the Politics of Property in Colonial Hong Kong By

Speculative Modern: Urban Forms and the Politics of Property in Colonial Hong Kong by Cecilia Louise Chu A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Nezar AlSayyad, Chair Professor C. Greig Crysler Professor Eugene F. Irschick Spring 2012 Speculative Modern: Urban Forms and the Politics of Property in Colonial Hong Kong Copyright 2012 by Cecilia Louise Chu 1 Abstract Speculative Modern: Urban Forms and the Politics of Property in Colonial Hong Kong Cecilia Louise Chu Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture University of California, Berkeley Professor Nezar AlSayyad, Chair This dissertation traces the genealogy of property development and emergence of an urban milieu in Hong Kong between the 1870s and mid 1930s. This is a period that saw the transition of colonial rule from one that relied heavily on coercion to one that was increasingly “civil,” in the sense that a growing number of native Chinese came to willingly abide by, if not whole-heartedly accept, the rules and regulations of the colonial state whilst becoming more assertive in exercising their rights under the rule of law. Long hailed for its laissez-faire credentials and market freedom, Hong Kong offers a unique context to study what I call “speculative urbanism,” wherein the colonial government’s heavy reliance on generating revenue from private property supported a lucrative housing market that enriched a large number of native property owners. Although resenting the discrimination they encountered in the colonial territory, they were able to accumulate economic and social capital by working within and around the colonial regulatory system. -

French Firms in Macau -.:: GEOCITIES.Ws

TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIRMS: BREAKDOWN BY SECTORS 3 LIST OF FIRMS BY ALPHABETICAL ORDER 9 LIST OF FIRMS BY PARENT COMPANY 89 LIST OF FIRMS BY PARENT COMPANY 95 French Firms in Hong Kong and Macau - 1999 Edition LIST OF FIRMS: BREAKDOWN BY SECTORS Advertising EURO RSCG PARTNERSHIP Beverages, wines & spirits FIRST VISION LTD. ADET SEWARD FLEXICOM BELCOMBE CO. LTD. FRENCH FASHION LTD CALDBECKS LTD. IMAGE SOLUTIONS CASELLA FAR EAST LIMITED MERCURY PUBLICITY (HK) LTD. CHATEAU DE LA TOUR (ASIA) LTD. SPICY CREATION HK LTD. CHEVAL QUANCARD ASIA LTD CREACTION INTERNATIONAL LTD. CULINA (H.K.) LIMITED Aeronautics DUISDALE LTD. AIRBUS INDUSTRIE-MACAO EURO LUXE (HONG KONG) LTD. DASSAULT FALCON JET CORP FICOFI (INTERNATIONAL) LTD. ELTRA AERONAUTICS FIMOXY CO LTD. METROJET LTD. GRANDS CRUS DE FRANCE LTD. / FRENCH WINE J.L.C. & MOUEIX FAR EAST LTD. JEAN PHILIPPE INTERNATIONAL (HK) LTD Agriculture - Foodstuffs MARTELL FAR EAST TRADING LTD. MEGAREVE AMOY FOOD LTD. MOET HENNESSY ASIA PACIFIC ASIATIQUE EUROPEENNE DE COMMERCE LTD. OLIVIER ASIA LTD. BALA FAR EAST LIMITED OLIVIER HONG KONG LTD. CULINA (H.K.) LIMITEDDELIFRANCE (HK) LTD. PR ASIA DANONE REMY CHINA & HK LTD. EURO LUXE (HONG KONG) LTD. REMY PACIFIQUE LTD. FARGO SERVICES (H.K.) LTD. RICHE MONDE LTD. GRANDS CRUS DE FRANCE LTD. / FRENCH WINE SAVEURS INTERNATIONAL LIMITED INNOLEDGE INTERNATIONAL LTD. SINO-FRENCH RESOURCES LTD. INTERNATIONAL COMMERCIAL AGENCIES SOPEXA LTD. LA ROSE NOIRE TAHLEIA LTD. LESAFFRE (FAR EAST) LTD. LVMH ASIA PACIFIC LTD. OLIVIER ASIA LTD. OLIVIER HONG KONG LTD. Building construction SOPEXA LTD. BACHY SOLETANCHE GROUP TAHLEIA LTD. BOUYGUES DRAGAGES ASIA VALRHONA FAR EAST BYME ENGINEERING (HK) LTD CAMPENON BERNARD SGE DEXTRA PACIFIC LTD. -

In the Court of Final Appeal of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region

FACV Nos. 9 & 10 of 2006 IN THE COURT OF FINAL APPEAL OF THE HONG KONG SPECIAL ADMINISTRATIVE REGION FINAL APPEAL NOS. 9 & 10 OF 2006 (CIVIL) (ON APPEAL FROM CACV NOS. 297 & 298 OF 2004) _______________________ Between: SIEGFRIED ADALBERT UNRUH Plaintiff (Respondent) - and - HANS-JOERG SEEBERGER 1st Defendant (1st Appellant) EGANAGOLDPFEIL (HOLDINGS) LIMITED 2nd Defendant (2nd Appellant) _______________________ Court: Chief Justice Li , Mr Justice Bokhary PJ, Mr Justice Chan PJ, Mr Justice Ribeiro PJ and Mr Justice McHugh NPJ Dates of Hearing: 15, 16 and 18 January 2007 Date of Judgment: 9 February 2007 _______________________ J U D G M E N T _______________________ Chief Justice Li: 1. I agree with the judgment of Mr Justice Ribeiro PJ. — 2 — Mr Justice Bokhary PJ: 2. I agree with the judgment of Mr Justice Ribeiro PJ. Mr Justice Chan PJ: 3. I have read the judgment of Mr Justice Ribeiro PJ in draft. I agree entirely with his comprehensive analysis and conclusions. I too would dispose of these appeals as proposed by him in the concluding paragraph of his judgment. Mr Justice Ribeiro PJ: A. The parties and the issues 4. On 19 September 1992, the plaintiff (“Mr Unruh”) entered into a Memorandum of Agreement (“the MoA”) with the 1st defendant (“Mr Seeberger”). The MoA provides that under certain circumstances, Mr Unruh is to become entitled to payment of a “Special Bonus”. Mr Unruh contends that such entitlement has arisen and, not having been paid, brought proceedings to recover the same from Mr Seeberger and from the 2nd defendant (“Egana”, formerly called Haru International (Holdings) Limited). -

Paths of Justice

PATHS OF JUSTICE Johannes M. M. Chan http://www.pbookshop.com Hong Kong University Press The University of Hong Kong Pokfulam Road Hong Kong www.hkupress.hku.hk © 2018 Hong Kong University Press ISBN 978-988-8455-93-5 (hardback) ISBN 978-988-8455-94-2 (Paperback) All rights reserved. No http://www.pbookshop.comportion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed and bound in Hong Kong, China Preface What is justice? Can justice be done? Jurists and philosophers have been asking these questions for centuries. While there is a huge body of learned work on these questions, no theory can tell what justice is or whether justice has been done in any particular case. At the end of the day, justice perhaps just lies in the hearts of ordinary people. Like the concept of the reasonable man, justice may not be something that can be formulated in abstraction but by and large is something that we recognize when we see it in practice. I have long wanted to write a book to explore these themes through real cases. As an academic lawyer, I have the privilege of being involved in the two related but in fact quite separate worlds of academia and legal practice.