Is US Health Really the Best in the World?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boxing's Biggest Stars Collide on the Big Screen in "THE ONE: Floyd ‘Money' Mayweather Vs

July 30, 2013 Boxing's Biggest Stars Collide On The Big Screen In "THE ONE: Floyd ‘Money' Mayweather vs. Canelo Alvarez" Exciting Co-Main Event Features Danny Garcia and Lucas Matthysse NCM Fathom Events, Mayweather Promotions, Golden Boy Promotions, Canelo Promotions, SHOWTIME PPV® and O'Reilly Auto Parts Bring Long-Awaited Fights to Movie Theaters Nationwide Live from Las Vegas on Saturday, Sept. 14 CENTENNIAL, Colo.--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- Fans across the country can watch the much-anticipated match-up between the reigning boxing kings of the United States and Mexico when NCM Fathom Events, Mayweather Promotions, Golden Boy Promotions, Canelo Promotions, SHOWTIME PPV® and O'Reilly Auto Parts bring boxing's biggest star Floyd "Money" Mayweather and Super Welterweight World Champion Canelo Alvarez to the big screen. In what is anticipated to be one of the biggest fights in boxing history, both Mayweather and Canelo will defend their undefeated records in an action-packed, live broadcast from the MGM Grand Garden Arena in Las Vegas, Nev. on Mexican Independence Day weekend. "The One: Mayweather vs. Canelo" will be broadcast to select theaters nationwide on Saturday, Sept. 14 at 9:00 p.m. ET / 8:00 p.m. CT / 7:00 p.m. MT / 6:00 p.m. PT / 5:00 p.m. AK / 3:00 p.m. HI. In addition to the explosive main event, Unified Super Lightweight World Champion Danny "Swift" Garcia and WBC Interim Super Lightweight World Champion Lucas "The Machine" Matthysse will meet in a bout fans have been clamoring to see. Garcia vs. Matthysse will anchor the fight's undercard with additional bouts to be announced shortly. -

Like UFC Champion Conor Mcgregor)

Achieve Your Goals Podcast #85 - How To Create Your Own Destiny (Like UFC Champion Conor McGregor) Nick: Welcome, to the Achieve Your Goals Podcast with Hal Elrod. I'm your host Nick Palkowski and you're listening to the show that is guaranteed to help you take your life to the next level faster than you ever thought possible. In each episode you'll learn from someone who has achieved extraordinary goals that most haven't. Is the author of number one best selling book The Miracle Morning, a hall of fame, and business achiever, and international keynote speaker, ultra marathon runner and the founder of vipsuccesscoaching.com. Mr. Hal Elrod. Hal: All right, Achieve Your Goals Podcast. Listeners welcome, this is your host Hal Elrod, and thank you for tuning in to what is sure to be an eye opening and surprisingly fun episode of the Achieve Your Goals Podcast. This will be a little different than anything we've ever done before. I do have a guest. I'm going to wait for a few minutes to tell you who that is. And the topic of the podcast today revolves around my favorite sport and specifically around the number one star, if you will. One of the top fighters in the world. And when it comes to my favorite sport, as many of you may know, I'm a huge fan of the sport known as M-M-A, which stands for Mixed Martial Arts, or what's popularly known as the UFC, which is the kind of the NBA of mix martial arts. -

Bma Presents 2019 Jazz in the Sculpture Garden Concerts

BMA PRESENTS 2019 JAZZ IN THE SCULPTURE GARDEN CONCERTS Tickets on sale June 5 for Vijay Iyer, Matana Roberts, and Wendel Patrick Quartet BALTIMORE, MD (May 2, 2018)—The Baltimore Museum of Art’s (BMA) popular summer jazz series returns with three concerts featuring national and regional talent in the museum’s lush gardens. Featured performers are Vijay Iyer (June 29), Matana Roberts (July 13), and the Wendel Patrick Quartet (July 27). General admission tickets are $50 for a single concert or $135 for the three-concert series. BMA Member tickets are $35 for a single concert or $90 for the three-concert series. Tickets are on sale Wednesday, June 5, and will sell out quickly, so reservations are highly recommended. Tickets for BMA Members are available beginning Wednesday, May 29. Saturday, June 29 – Vijay Iyer, jazz piano Grammy-nominated composer-pianist Vijay Iyer sees jazz as “creating beauty and changing the world” (NPR) and is recognized as “one of the best in the world at what he does.” (Pitchfork). Saturday, July 13 – Matana Roberts, experimental jazz saxophonist As “the spokeswoman for a new, politically conscious and refractory music scene” (Jazzthetik), Matana Roberts’ music has been praised for its “originality and … historic and social power” (music critic Peter Margasak). Saturday, July 27 – Wendel Patrick Quartet Wendel Patrick is the “wildly talented” (Baltimore Sun) alter ego of acclaimed classical and jazz pianist Kevin Gift. The Baltimore-based musician creates a unique blend of jazz, electronica, and hip hop. The BMA’s beautiful Janet and Alan Wurtzburger Sculpture Garden presents 19 early modernist works by artists such as Alexander Calder, Isamu Noguchi, and Auguste Rodin amidst a flagstone terrace and fountain. -

Poe's Baltimore

http://knowingpoe.thinkport.org/ Poe’s Baltimore Content Overview This is an outline of the information found on each location on the interactive map. As students explore the map online, you will note the following color coding system: ü Modern Sites are yellow ü Sites Then and Now are green ü Poe-era sites are red In addition, all locations include images. Modern Sites Modern Inner Harbor (Harborplace) NOW: Harborplace is a fairly recent addition to Baltimore’s landscape. Completed in 1980, Harborplace and its close relatives, the Maryland Science Center and the National Aquarium at Baltimore, have attracted millions of visitors to the city each year. If you were wondering why Harborplace appears to be out in the harbor on the 1838 map…it’s because it was! As late as 1950, the Inner Harbor was just that – the innermost dock in Baltimore Harbor for passenger, freight, and government ships. But the docks were old and rotting, so around 1970 the city tore them down. The plans for developing the shopping pavilions at Harborplace called for more space. The city did just that—using concrete and pylons to add almost 100 feet of shoreline where the rotting docks had been. The result was the Inner Harbor area – complete with shops and large pathways – that you can walk around today. THEN: In Poe’s day, the Inner Harbor area was a thriving seaport. Ships were being built in nearby Fells Point. A new, lively form of transportation— called a “steamer” (a steam-powered boat)—was becoming a more and more common sight. -

Production Notes

A Film by John Madden Production Notes Synopsis Even the best secret agents carry a debt from a past mission. Rachel Singer must now face up to hers… Filmed on location in Tel Aviv, the U.K., and Budapest, the espionage thriller The Debt is directed by Academy Award nominee John Madden (Shakespeare in Love). The screenplay, by Matthew Vaughn & Jane Goldman and Peter Straughan, is adapted from the 2007 Israeli film Ha-Hov [The Debt]. At the 2011 Beaune International Thriller Film Festival, The Debt was honoured with the Special Police [Jury] Prize. The story begins in 1997, as shocking news reaches retired Mossad secret agents Rachel (played by Academy Award winner Helen Mirren) and Stephan (two-time Academy Award nominee Tom Wilkinson) about their former colleague David (Ciarán Hinds of the upcoming Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy). All three have been venerated for decades by Israel because of the secret mission that they embarked on for their country back in 1965-1966, when the trio (portrayed, respectively, by Jessica Chastain [The Tree of Life, The Help], Marton Csokas [The Lord of the Rings, Dream House], and Sam Worthington [Avatar, Clash of the Titans]) tracked down Nazi war criminal Dieter Vogel (Jesper Christensen of Casino Royale and Quantum of Solace), the feared Surgeon of Birkenau, in East Berlin. While Rachel found herself grappling with romantic feelings during the mission, the net around Vogel was tightened by using her as bait. At great risk, and at considerable personal cost, the team’s mission was accomplished – or was it? The suspense builds in and across two different time periods, with startling action and surprising revelations that compel Rachel to take matters into her own hands. -

What's New in London for 2016 Attractions

What’s new in London for 2016 Lumiere London, 14 – 17 January 2016. Credit - Janet Echelman. Attractions ZSL London Zoo - Land of the Lions ZSL London Zoo, opening spring 2016 Land of the Lions will provide state-of-the-art facilities for a breeding group of endangered Asiatic lions, of which only 400 remain in the wild. Giving millions of people the chance to get up-close to the big cats, visitors to Land of the Lions will be able to see just how closely humans and lions live in the Gir Forest, with tantalising glimpses of the lions’ habitat appearing throughout a bustling Indian ‘village’. For more information contact Rebecca Blanchard on 020 7449 6236 / [email protected] Arcelor Mittal Orbit giant slide Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park, opening spring 2016 Anish Kapoor has invited Belgian artist Carsten Höller to create a giant slide for the ArcelorMittal Orbit. This is a unique collaboration between two of the world’s leading artists and will be a major new art installation for the capital. The slide will be the world’s longest and tallest tunnel slide, measuring approximately 178m long and will be 76m high. There will be transparent sections on the slide so you can marvel at the view. For more information contact Victoria Coombes on 020 7421 2500 / [email protected] New Tate Modern Southbank, 17 June 2016 The new Tate Modern will be unveiled with a complete re-hang, bringing together much-loved works from the collection with new acquisitions made for the nation since Tate Modern first opened in 2000. -

The Top 365 Wrestlers of 2019 Is Aj Styles the Best

THE TOP 365 WRESTLERS IS AJ STYLES THE BEST OF 2019 WRESTLER OF THE DECADE? JANUARY 2020 + + INDY INVASION BIG LEAGUES REPORT ISSUE 13 / PRINTED: 12.99$ / DIGITAL: FREE TOO SWEET MAGAZINE ISSUE 13 Mohammad Faizan Founder & Editor in Chief _____________________________________ SENIOR WRITERS.............Nick Whitworth ..........................................Tom Yamamoto ......................................Santos Esquivel Jr SPECIAL CONTRIBUTOR....…Chuck Mambo CONTRIBUTING WRITERS........Matt Taylor ..............................................Antonio Suca ..................................................7_year_ish ARTIST………………………..…ANT_CLEMS_ART PHOTOGRAPHERS………………...…MGM FOTO .........................................Pw_photo2mass ......................................art1029njpwphoto ..................................................dasion_sun ............................................Dragon000stop ............................................@morgunshow ...............................................photosneffect ...........................................jeremybelinfante Content Pg.6……………….……...….TSM 100 Pg.28.………….DECADE AWARDS Pg.29.……………..INDY INVASION Pg.32…………..THE BIG LEAGUES THE THOUGHTS EXPRESSED IN THE MAGAZINE IS OF THE EDITOR, WRITERS, WRESTLERS & ADVERTISERS. THE MAGAZINE IS NOT RELATED TO IT. ANYTHING IN THIS MAGAZINE SHOULD NOT BE REPRODUCED OR COPIED. TSM / SEPT 2019 / 2 TOO SWEET MAGAZINE ISSUE 13 First of all I’ll like to praise the PWI for putting up a 500 list every year, I mean it’s a lot of work. Our team -

Film Stars Don't Die in Liverpool

FILM STARS DON'T DIE IN LIVERPOOL Written by Matt Greenhalgh 1. 1 INT. LEADING LADY’S DRESSING ROOM - NIGHT 1 Snug and serene. An illuminated vanity mirror takes centre stage emanating a welcoming glamorous glow. A SERIES OF C/UP’s: A TDK AUDIO TAPE inserted into a slim SONY CASSETTE PLAYER immediately placing us in the late 70’s/early 80’s. A CHIPPED VARNISHED FINGER NAIL presses play.. ‘Song For Guy’ by Elton John (Gloria’s favourite track) drifts in... OUR LEADING LADY sits in the dresser. Find her through shards of focus and reflections as she transforms.. warming her vocal chords as she goes: GLORIA (O.C.) ‘La Poo Boo Moo..’ Eye-line pencil; cherry-red lipstick; ‘Saks of Fifth Avenue’ COMPACT MIRROR, intricately engraved with “Love Bogie ’In A Lonely Place’ 1950”; Elnett hair laquer; Chanel perfume. A larger BROKEN HAND-MIRROR. A GOLDEN LOVE HEART PENDANT (opens with a sychronised tune). All Gloria’s ‘tools’ procured from a TATTY GREEN WASH-BAG, a trusted witness to her ‘process’ probably a thousand times or more. GLORIA (O.C.) (CONT’D) ‘Major Mickey’s Malt Makes Me Merry.’ Costume: Peek at pale flesh and slim limbs as she climbs into a black, pleated wrap around dress with a plunging neckline; black stockings and princess slippers.. the dress hangs loose, too loose.. the belt tightened as far as it can go. A KNOCK ON THE DOOR STAGE MANANGER (V.O.) Five minutes Miss Grahame. GLORIA (O.C.) Thanks honey. Gloria’s tongue CLUCKS the roof of her mouth in approval, it’s one of her things. -

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra Sound

TEACHER’S GUIDE REFLECT RESPOND REMIX THE CHICAGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA SOUND A Guide to the Chicago Symphony Orchestra School Concerts november 28 & 29, 2018 10:15 a.m. & 12:00 p.m. celebrating 100 years of the cso’s concert series for children 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Letter from the Negaunee Music Institute Staff 1 Program Information 2 Lesson 1: It Takes a Team 3 Lesson 2: Why Music Matters 11 Postconcert Reflection 16 Composers’ History 21 Acknowledgments 25 Teacher’s Guide Chicago Symphony Orchestra Dear Teachers, Welcome to the Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s 2018/19 School Concert season. This year we are celebrating the 100th season of the CSO’s concert series for children. Each concert this season will reflect on the ensemble’s past, discover the ways in which orchestra musicians respond to each other as well as communities all over the globe, and consider how symphonic music is being “remixed” to take us into a new and exciting orchestral future. Familiarizing your students with the repertoire prior to the concert will make the live performance even more engaging and rewarding. In addition to exposing your students to this music through the lessons included in this Teacher’s Guide, consider additional opportunities for them to hear it during your school day: at the start of your morning routine or during quiet activities, such as journaling. Depending on your teaching schedule, some of the activities in this guide could be completed after your concert. Students’ enjoyment of this music doesn’t have to stop after the performance! This curriculum will engage and guide students to listen for specific things in each piece of music. -

STARS Oshihiyi

University of Central Florida STARS Text Materials of Central Florida Central Florida Memory 1-1-1920 Oshihiyi John B. Stetson University Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/cfm-texts University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Yearbook is brought to you for free and open access by the Central Florida Memory at STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Text Materials of Central Florida by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation John B. Stetson University, "Oshihiyi" (1920). Text Materials of Central Florida. 408. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/cfm-texts/408 ^igJ^^I'ggm^^^^^^l^g^'^^^^^^lih^^gSiJl^ilSgM^i^gi^gJS^:^^ I i i i Gift of Editorial Staff m <2. / This book must not be taken from the Library building. Page One }jm Page Two 4 z" zvho ' r loyal and gent 1I ,.V,7 v this Universitv ^/'iSlrt Dedicated to G, Henry Stetson^ IlllJJ our beloved friend^ who has al ways been a loyal and generous helper of this University. % ,JJi Ll ^3 3 Page Three r Page Four .'"OO^ lEbitor'8 J^oreworb r<>90 In presenting to you. Fellow Students, The Oshihiyi of '20, which as far as might be, we have tried to make the expression of our life at the University, the editors wish, first, to thank those who have given their hearty co-operation in making the book what it is, and then that it may be one of our most treasured volumes, in after years. -

Trade for Peace: Integration of Fragile States Into the Global Economy As a Pathway Towards Peace and Resilience”

WTO PUBLIC FORUM 2018 “TRADE FOR PEACE: INTEGRATION OF FRAGILE STATES INTO THE GLOBAL ECONOMY AS A PATHWAY TOWARDS PEACE AND RESILIENCE” Keynote Speech by the g7+ Eminent Person, H.E. Kay Rala Xanana Gusmão Geneva, 4 October 2018 Excellencies, Ministers, Ambassador Alan Wolff Deputy Director- General, Ladies and Gentlemen, Good afternoon. I am honoured to be given the opportunity to address you today on a matter that is impactful on the lives of over 1.5 billion of people, who suffered and are suffering by decades of wars and conflicts. These countries are sometime referred to as failed, failing or fragile states in the global discourse and have been the focus of humanitarian, and development organizations assistance, for decades now. 1 The g7+ (with the little “g” to avoid confusion) constitute 20 of those so called “fragile” states. While the world has been increasingly integrated and connected through trade, cooperation, and technology, these countries are left out or “farthest left behind”, as it is said nowadays. Yet, these countries have the potential to provide the fuel for the economic prosperity of the World. Let me mention some of them: Afghanistan, lies across the silk road that connects civilizations and has the potential of regional development hub. It has precious minerals that has not been exploited yet. Instead, it has been the contesting ground for hegemony in the region at the cost of millions of Afghans who have been the victim of this circus. Somalia, has one of the longest coastlines in Africa that can be a destination for tourism, and an exceptional ground for fisheries. -

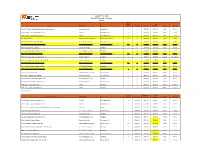

July 2019 Title Grid Event TV Title Grid - Version 2 5/29/2019 Approx Length Final Events Distributor Genre (Hours) Preshow Premiere Exhibition SRP Rating

July 2019 Title Grid Event TV Title Grid - Version 2 5/29/2019 Approx Length Final Events Distributor Genre (hours) Preshow Premiere Exhibition SRP Rating 2018 NPC Women’s National Bodybuilding Championships Stonecutter Media Bodybuilding 2.5 N 07/05/19 07/31/19 $9.95 TV-14 AXS TV Fights: Legacy Fighting Alliance 64 AXS TV Mixed Martial Arts 2.5 N 07/13/19 07/31/19 $9.95 TV-14 AXS TV Fights: Legacy Fighting Alliance 65 AXS TV Mixed Martial Arts 2.5 N 07/28/19 07/31/19 $9.95 TV-14 Bluegrass Journey MVD Entertainment Group Music / Documentary 1.5 N 07/03/19 07/31/19 $5.95 TV-PG Code Red: Shameless Acts of Stupidity XTV: Xtreme Television Uncensored TV 1 N 07/02/19 07/31/19 $9.95 TV-MA Ellie Kemper: Unbreakable Comedy Gala Bruder Releasing, Inc. Comedy / Stand-Up 1.5 N 07/12/19 07/31/19 $7.95 TV-PG Extreme Legends: Tito Santana Stonecutter Media Wrestling 1 N 07/17/19 07/31/19 $7.95 TV-14 Female Wrestling's Most Violent Brawls 68 The Wrestling Zone, Inc. Wrestling 1 N 07/19/19 07/31/19 $7.95 TV-14 Howie Mandel All-Star Comedy Gala Bruder Releasing, Inc. Comedy / Stand-Up 1.5 N 07/03/19 07/31/19 $7.95 TV-PG IMPACT Wrestling: Slammiversary XVII (Live) Impact Wrestling Wrestling 4 Y 07/07/19 07/07/19 $39.95 TV-14 D,L,V IMPACT Wrestling: Slammiversary XVII (Replay) Impact Wrestling Wrestling 3 N 07/09/19 07/30/19 $39.95 TV-14 D,L,V Neil Patrick Harris: Circus Awesomeus Bruder Releasing, Inc.