Poe's Baltimore

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boxing's Biggest Stars Collide on the Big Screen in "THE ONE: Floyd ‘Money' Mayweather Vs

July 30, 2013 Boxing's Biggest Stars Collide On The Big Screen In "THE ONE: Floyd ‘Money' Mayweather vs. Canelo Alvarez" Exciting Co-Main Event Features Danny Garcia and Lucas Matthysse NCM Fathom Events, Mayweather Promotions, Golden Boy Promotions, Canelo Promotions, SHOWTIME PPV® and O'Reilly Auto Parts Bring Long-Awaited Fights to Movie Theaters Nationwide Live from Las Vegas on Saturday, Sept. 14 CENTENNIAL, Colo.--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- Fans across the country can watch the much-anticipated match-up between the reigning boxing kings of the United States and Mexico when NCM Fathom Events, Mayweather Promotions, Golden Boy Promotions, Canelo Promotions, SHOWTIME PPV® and O'Reilly Auto Parts bring boxing's biggest star Floyd "Money" Mayweather and Super Welterweight World Champion Canelo Alvarez to the big screen. In what is anticipated to be one of the biggest fights in boxing history, both Mayweather and Canelo will defend their undefeated records in an action-packed, live broadcast from the MGM Grand Garden Arena in Las Vegas, Nev. on Mexican Independence Day weekend. "The One: Mayweather vs. Canelo" will be broadcast to select theaters nationwide on Saturday, Sept. 14 at 9:00 p.m. ET / 8:00 p.m. CT / 7:00 p.m. MT / 6:00 p.m. PT / 5:00 p.m. AK / 3:00 p.m. HI. In addition to the explosive main event, Unified Super Lightweight World Champion Danny "Swift" Garcia and WBC Interim Super Lightweight World Champion Lucas "The Machine" Matthysse will meet in a bout fans have been clamoring to see. Garcia vs. Matthysse will anchor the fight's undercard with additional bouts to be announced shortly. -

THE VILLAGE at FALLSWAY MULTIFAMILY DEVELOPMENT in an OPPORTUNITY ZONE BALTIMORE, MARYLAND the Village at Fallsway

THE VILLAGE AT FALLSWAY MULTIFAMILY DEVELOPMENT IN AN OPPORTUNITY ZONE BALTIMORE, MARYLAND The Village at Fallsway THIS CONFIDENTIAL OFFERING MEMORANDUM (“Offering Memorandum”) is being furnished to the recipient (the “Recipient”) solely for the Recipient’s own limited use in considering whether to provide financing for The Village at Fallsway located at 300-320 North Front Street, 300-312 North High Street, and 300 Fallsway, Baltimore, MD (the “Property”), on behalf of Airo Capital Management (the “Sponsor”). This confidential information does not purport to be all-inclusive nor does it purport to contain all the information that a prospective investor may desire. Neither Avison Young, the Sponsor nor any of their respective partners, managers, officers, employees or agents makes any representation, guarantee or warranty, expressed or implied, as to the accuracy or completeness of this Offering Memorandum or any of its contents and no legal liability is assumed or shall be implied with respect thereto. The Recipient agrees that: (a) the Offering Memorandum and its contents are confidential information, except for such information contained in the Offering Memorandum that is a matter of public record; (b) the Recipient and the Recipient’s employees, agents, and consultants (collectively, the “need to know parties”) will hold and treat the Offering Memorandum in the strictest of confidence, and the Recipient and the need to know parties will not, directly or indirectly, disclose or permit anyone else to disclose its contents to any other person, firm, or entity without the prior written authorization of the Sponsor; and, (c) the Recipient and the need to know parties will not use, or permit to be used, this Offering Memorandum or its contents in any fashion or manner detrimental to the interest of the Sponsor or for any purpose other than use in considering whether to invest into the Property. -

The Gallery / Harborplace 200 E

THE GALLERY / HARBORPLACE 200 E. Pratt Street / 111 S. Calvert Street Baltimore, Maryland AREA AMENITIES FLEXIBLE OFFICE SPACE PROPERTY HIGHLIGHTS Outstanding views overlooking Baltimore’s THE GALLERY / famed Inner Harbor Parking garage (1,190 cars) with 24/7 access HARBORPLACE New fitness center FREE to all tenants 200 E. Pratt Street 600-room Renaissance Harborplace Hotel interconnected 111 S. Calvert Street Lobby guard on duty and fully automated New 30,000 square foot high-end “Spaces” co-working facility Baltimore, Maryland Retail amenities including new full-service restaurant COMING SOON! -- Dunkin'® HARBOR VIEW MATTHEW SEWARD BRONWYN LEGETTE Senior Director Director +1 410 347 7549 +1 410 347 7565 [email protected] [email protected] One East Pratt Street, Suite 700 | Baltimore, MD 21202 Main +1 410 752 4285 | Fax +1 576 9031 cushmanwakefield.com ©2019 Cushman & Wakefield. All rights reserved. The information contained in this communication is strictly confidential. This information has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable but has not been verified. No warranty or representation, express or implied, is made as to the condition of the property (or properties) referenced herein or as to the accuracy or completeness of the information contained herein, and same is submitted subject to errors, omissions, change of price, rental or other conditions, withdraw- al without notice, and to any special listing conditions imposed by the property owner(s). Any projections, opinions or estimates are subject -

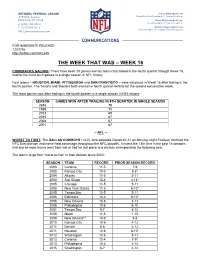

The Week That Was – Week 16

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 12/27/16 http://twitter.com/NFL345 THE WEEK THAT WAS – WEEK 16 COMEBACKS GALORE: There have been 70 games won by teams that trailed in the fourth quarter through Week 16, tied for the most such games in a single season in NFL history. Four teams – HOUSTON, MIAMI, PITTSBURGH and SAN FRANCISCO – were victorious in Week 16 after trailing in the fourth quarter. The Texans and Steelers both overcame fourth quarter deficits for the second consecutive week. The most games won after trailing in the fourth quarter in a single season in NFL history: SEASON GAMES WON AFTER TRAILING IN 4TH QUARTER IN SINGLE SEASON 2016 70 1989 70 2013 69 2015 67 2008 67 2001 67 -- NFL -- WORST TO FIRST: The DALLAS COWBOYS (13-2), who defeated Detroit 42-21 on Monday Night Football, clinched the NFC East division and home-field advantage throughout the NFC playoffs. It marks the 13th time in the past 14 seasons that one or more teams went from last or tied for last place to a division championship the following year. The teams to go from “worst-to-first” in their division since 2003: SEASON TEAM RECORD PRIOR SEASON RECORD 2003 Carolina 11-5 7-9 2003 Kansas City 13-3 8-8* 2004 Atlanta 11-5 5-11 2004 San Diego 12-4 4-12* 2005 Chicago 11-5 5-11 2005 New York Giants 11-5 6-10* 2005 Tampa Bay 11-5 5-11 2006 Baltimore 13-3 6-10* 2006 New Orleans 10-6 3-13 2006 Philadelphia 10-6 6-10 2007 Tampa Bay 9-7 4-12 2008 Miami 11-5 1-15 2009 New Orleans** 13-3 8-8 2010 Kansas City 10-6 4-12 2011 Denver 8-8 4-12 2011 Houston 10-6 6-10* 2012 Washington 10-6 5-11 2013 Carolina 12-4 7-9* 2013 Philadelphia 10-6 4-12 2015 Washington 8-7 4-12 2016 Dallas 13-2 4-12 * Tied for last place ** Won Super Bowl -- NFL -- HISTORIC WINNERS: The GREEN BAY PACKERS defeated Minnesota 38-25 on Saturday at Lambeau Field. -

Like UFC Champion Conor Mcgregor)

Achieve Your Goals Podcast #85 - How To Create Your Own Destiny (Like UFC Champion Conor McGregor) Nick: Welcome, to the Achieve Your Goals Podcast with Hal Elrod. I'm your host Nick Palkowski and you're listening to the show that is guaranteed to help you take your life to the next level faster than you ever thought possible. In each episode you'll learn from someone who has achieved extraordinary goals that most haven't. Is the author of number one best selling book The Miracle Morning, a hall of fame, and business achiever, and international keynote speaker, ultra marathon runner and the founder of vipsuccesscoaching.com. Mr. Hal Elrod. Hal: All right, Achieve Your Goals Podcast. Listeners welcome, this is your host Hal Elrod, and thank you for tuning in to what is sure to be an eye opening and surprisingly fun episode of the Achieve Your Goals Podcast. This will be a little different than anything we've ever done before. I do have a guest. I'm going to wait for a few minutes to tell you who that is. And the topic of the podcast today revolves around my favorite sport and specifically around the number one star, if you will. One of the top fighters in the world. And when it comes to my favorite sport, as many of you may know, I'm a huge fan of the sport known as M-M-A, which stands for Mixed Martial Arts, or what's popularly known as the UFC, which is the kind of the NBA of mix martial arts. -

Bma Presents 2019 Jazz in the Sculpture Garden Concerts

BMA PRESENTS 2019 JAZZ IN THE SCULPTURE GARDEN CONCERTS Tickets on sale June 5 for Vijay Iyer, Matana Roberts, and Wendel Patrick Quartet BALTIMORE, MD (May 2, 2018)—The Baltimore Museum of Art’s (BMA) popular summer jazz series returns with three concerts featuring national and regional talent in the museum’s lush gardens. Featured performers are Vijay Iyer (June 29), Matana Roberts (July 13), and the Wendel Patrick Quartet (July 27). General admission tickets are $50 for a single concert or $135 for the three-concert series. BMA Member tickets are $35 for a single concert or $90 for the three-concert series. Tickets are on sale Wednesday, June 5, and will sell out quickly, so reservations are highly recommended. Tickets for BMA Members are available beginning Wednesday, May 29. Saturday, June 29 – Vijay Iyer, jazz piano Grammy-nominated composer-pianist Vijay Iyer sees jazz as “creating beauty and changing the world” (NPR) and is recognized as “one of the best in the world at what he does.” (Pitchfork). Saturday, July 13 – Matana Roberts, experimental jazz saxophonist As “the spokeswoman for a new, politically conscious and refractory music scene” (Jazzthetik), Matana Roberts’ music has been praised for its “originality and … historic and social power” (music critic Peter Margasak). Saturday, July 27 – Wendel Patrick Quartet Wendel Patrick is the “wildly talented” (Baltimore Sun) alter ego of acclaimed classical and jazz pianist Kevin Gift. The Baltimore-based musician creates a unique blend of jazz, electronica, and hip hop. The BMA’s beautiful Janet and Alan Wurtzburger Sculpture Garden presents 19 early modernist works by artists such as Alexander Calder, Isamu Noguchi, and Auguste Rodin amidst a flagstone terrace and fountain. -

Get Charmed in Charm City - Baltimore! "…The Coolest City on the East Coast"* Post‐Convention July 14‐17, 2018

CACI’s annual Convention July 8‐14, 2018 Get Charmed in Charm City - Baltimore! "…the Coolest City on the East Coast"* Post‐Convention July 14‐17, 2018 *As published by Travel+Leisure, www.travelandleisure.com, July 26, 2017. Panorama of the Baltimore Harbor Baltimore has 66 National Register Historic Districts and 33 local historic districts. Over 65,000 properties in Baltimore are designated historic buildings in the National Register of Historic Places, more than any other U.S. city. Baltimore - first Catholic Diocese (1789) and Archdiocese (1808) in the United States, with the first Bishop (and Archbishop) John Carroll; the first seminary (1791 – St Mary’s Seminary) and Cathedral (begun in 1806, and now known as the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary - a National Historic Landmark). O! Say can you see… Home of Fort McHenry and the Star Spangled Banner A monumental city - more public statues and monuments per capita than any other city in the country Harborplace – Crabs - National Aquarium – Maryland Science Center – Theater, Arts, Museums Birthplace of Edgar Allan Poe, Babe Ruth – Orioles baseball Our hotel is the Hyatt Regency Baltimore Inner Harbor For exploring Charm City, you couldn’t find a better location than the Hyatt Regency Baltimore Inner Harbor. A stone’s throw from the water, it gets high points for its proximity to the sights, a rooftop pool and spacious rooms. The 14- story glass façade is one of the most eye-catching in the area. The breathtaking lobby has a tilted wall of windows letting in the sunlight. -

Exclusive Offering Executive Summary

EXCLUSIVE OFFERING EXECUTIVE SUMMARY INVESTMENT HIGHLIGHTS • Best-in-Class, 279,712 RSF, Class A Office Asset → Newest Office Building Along Pratt Street • 10 Year Average Occupancy of 98% → Currently 86% Leased to 14 Tenants with 6.3 Years of WALT • Prestigious Pratt Street Address → Pratt Street Corridor has Averaged 92% Leased over the Past 5 Years • Outstanding Access via the Jones Falls Expressway (I-83) and I-395/I-95 → Penn Station (8 Minutes) and Baltimore- Washington International Airport (18 Minutes) Are Immediately Accessible • Sweeping Views of the Inner Harbor, the National Aquarium in Baltimore, Power Plant, and Federal Hill → The Property Features 4 Private Balconies and 1 Private Terrace • Countless Nearby Amenities Provided by Harborplace, The Gallery, and Surrounding Retailers • Residential Renaissance is Revitalizing Downtown Baltimore → Continued Office-to-Residential Conversions Holliday Fenoglio Fowler, L.P. (“HFF”), as exclusive representative for the Owner, is pleased to present this offering for the sale of the leasehold interest in 500 East Pratt (the “Property”), a 279,712 RSF office tower prominently located along Baltimore’s renowned Pratt Street. Currently 86% leased to 14 tenants with a weighted average remaining lease term of 6.3 years, 500 East Pratt features sweeping views of the Inner Harbor, outstanding multi-modal accessibility, and a full compliment of amenities in immediate walking distance of the Property. The newest building along Pratt Street, the Property is a true best-in-class asset and has an impressive 10 year average occupancy history of 98%, which is the best performing asset along the Pratt Street Corridor. For over two centuries, Pratt Street has been the center of Baltimore’s commercial district, offering outstanding multi-modal accessibility, views of Baltimore harbor, and proximity to the finest cultural and retail offerings in the City. -

Port Services Guide for Visiting Ships to Baltimore

PORT SERVICES GUIDE Port Services Guide For Visiting Ships to Baltimore Created by Sail Baltimore Page 1 of 17 PORT SERVICES GUIDE IMPORTANT PHONE NUMBERS IN BALTIMORE POLICE, FIRE & MEDICAL EMERGENCIES 911 Police, Fire & Medical Non-Emergencies 311 Baltimore City Police Information 410-396-2525 Inner Harbor Police (non-emergency) 410-396-2149 Southeast District - Fells Point (non-emergency) 410-396-2422 Sgt. Kenneth Williams Marine Police 410-396-2325/2326 Jeffrey Taylor, [email protected] 410-421-3575 Scuba dive team (for security purposes) 443-938-3122 Sgt. Kurt Roepke 410-365-4366 Baltimore City Dockmaster – Bijan Davis 410-396-3174 (Inner Harbor & Fells Point) VHF Ch. 68 US Navy Operational Support Center - Fort McHenry 410-752-4561 Commander John B. Downes 410-779-6880 (ofc) 443-253-5092 (cell) Ship Liaison Alana Pomilia 410-779-6877 (ofc) US Coast Guard Sector Baltimore - Port Captain 410-576-2564 Captain Lonnie Harrison - Sector Commander Commander Bright – Vessel Movement 410-576-2619 Search & Rescue Emergency 1-800-418-7314 General Information 410-789-1600 Maryland Port Administration, Terminal Operations 410-633-1077 Maryland Natural Resources Police 410-260-8888 Customs & Border Protection 410-962-2329 410-962-8138 Immigration 410-962-8158 Sail Baltimore 410-522-7300 Laura Stevenson, Executive Director 443-721-0595 (cell) Michael McGeady, President 410-942-2752 (cell) Nan Nawrocki, Vice President 410-458-7489 (cell) Carolyn Brownley, Event Assistant 410-842-7319 (cell) Page 2 of 17 PORT SERVICES GUIDE PHONE -

Production Notes

A Film by John Madden Production Notes Synopsis Even the best secret agents carry a debt from a past mission. Rachel Singer must now face up to hers… Filmed on location in Tel Aviv, the U.K., and Budapest, the espionage thriller The Debt is directed by Academy Award nominee John Madden (Shakespeare in Love). The screenplay, by Matthew Vaughn & Jane Goldman and Peter Straughan, is adapted from the 2007 Israeli film Ha-Hov [The Debt]. At the 2011 Beaune International Thriller Film Festival, The Debt was honoured with the Special Police [Jury] Prize. The story begins in 1997, as shocking news reaches retired Mossad secret agents Rachel (played by Academy Award winner Helen Mirren) and Stephan (two-time Academy Award nominee Tom Wilkinson) about their former colleague David (Ciarán Hinds of the upcoming Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy). All three have been venerated for decades by Israel because of the secret mission that they embarked on for their country back in 1965-1966, when the trio (portrayed, respectively, by Jessica Chastain [The Tree of Life, The Help], Marton Csokas [The Lord of the Rings, Dream House], and Sam Worthington [Avatar, Clash of the Titans]) tracked down Nazi war criminal Dieter Vogel (Jesper Christensen of Casino Royale and Quantum of Solace), the feared Surgeon of Birkenau, in East Berlin. While Rachel found herself grappling with romantic feelings during the mission, the net around Vogel was tightened by using her as bait. At great risk, and at considerable personal cost, the team’s mission was accomplished – or was it? The suspense builds in and across two different time periods, with startling action and surprising revelations that compel Rachel to take matters into her own hands. -

What's New in London for 2016 Attractions

What’s new in London for 2016 Lumiere London, 14 – 17 January 2016. Credit - Janet Echelman. Attractions ZSL London Zoo - Land of the Lions ZSL London Zoo, opening spring 2016 Land of the Lions will provide state-of-the-art facilities for a breeding group of endangered Asiatic lions, of which only 400 remain in the wild. Giving millions of people the chance to get up-close to the big cats, visitors to Land of the Lions will be able to see just how closely humans and lions live in the Gir Forest, with tantalising glimpses of the lions’ habitat appearing throughout a bustling Indian ‘village’. For more information contact Rebecca Blanchard on 020 7449 6236 / [email protected] Arcelor Mittal Orbit giant slide Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park, opening spring 2016 Anish Kapoor has invited Belgian artist Carsten Höller to create a giant slide for the ArcelorMittal Orbit. This is a unique collaboration between two of the world’s leading artists and will be a major new art installation for the capital. The slide will be the world’s longest and tallest tunnel slide, measuring approximately 178m long and will be 76m high. There will be transparent sections on the slide so you can marvel at the view. For more information contact Victoria Coombes on 020 7421 2500 / [email protected] New Tate Modern Southbank, 17 June 2016 The new Tate Modern will be unveiled with a complete re-hang, bringing together much-loved works from the collection with new acquisitions made for the nation since Tate Modern first opened in 2000. -

Sguidetom & Tbanks Ta Dium

2011 FAN’S GUIDE TO M&T BANK STADIUM TWENTY ELEVEN Dear Ravens Fan, FAN CODE OF CONDUCT fan bEhAviOr Welcome to m&T bank stadium! Ravens fans are the best in the NFL due to their enthusiasm, team support and sportsmanship. Fans help shape the Ravens’ image. We encourage our fans to create a Winning road playoff games in each of the past three seasons is an accomplishment high-energy environment in lending support to the team while maintaining a friendly and we can all take pride in, but our challenge remains to find a way to achieve our ultimate family-oriented atmosphere. Abusive/foul language or fighting will not be tolerated and goal…another Super Bowl!! will result in immediate ejection without refund. All game day employees work hand in hand at each of our games to ensure your game day experience is a positive one. Have Like you, we have high expectations for ourselves and believe that we are ready to take fun, root hard, show respect for the fans around you, but don’t be a jerk! The Ravens those next steps. General Manager Ozzie Newsome and Head Coach John Harbaugh reserve the right to eject any person whose behavior is unruly or illegal in nature: First- continue to work tirelessly to put the best team possible on the field – one that will make time offenders will be ejected from the stadium immediately. Second-time offenders will Baltimore proud and continue our quest to be an elite team in the NFL. lose their PSL’s and season tickets.