Martin Brings His Game, God

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

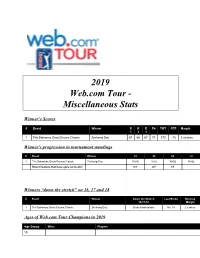

2019 Web.Com Tour - Miscellaneous Stats

2019 Web.com Tour - Miscellaneous Stats Winner’s Scores # Event Winner R R R R4 TOT RTP Margin 1 2 3 1 The Bahamas Great Exuma Classic Zecheng Dou 67 66 67 70 270 -18 2 strokes Winner’s progression in tournament standings # Event Winner 18 36 54 72 1 The Bahamas Great Exuma Classic Zecheng Dou T4(-5) 2(-6) 1(+5) 1(+2) Round leaders that have gone on to win* 0/1 0/1 1/1 Winners “down the stretch” on 16, 17 and 18 # Event Winner Down the Stretch Last Birdie Winning 16-17-18 Margin 1 The Bahamas Great Exuma Classic Zecheng Dou Birdie-birdie-birdie No. 18 2 strokes Ages of Web.com Tour Champions in 2019 Age Group Wins Players 19 20s 1 Zecheng Dou 30s 40s Oldest Youngest Date Tournament Winner Birthdate Age won 1/16 The Bahamas Great Exuma Classic Zecheng Dou 1-22-97 21 years, 11 months, 25 days Points list leaders, week-to-week # Week Leader Points Weeks@ 1 The Bahamas Great Exuma Classic Zecheng Dou 500 1 100 or fewer putts in a single tournament: Event Player Putts Winner’s Statistical Rankings: Event Winner Fairways GIR Putts The Bahamas Great Exuma Classic Zecheng Dou n/a n/a n/a The Bahamas Great Abaco Classic First-time winners: # Player Tournament Rookie winners: # Player Tournament Events with “preferred lies” # Event Rounds Total Events with suspensions/delay of play: 1. The Bahamas Great Exuma Classic – First-round play suspended at 5:47 p.m. due to darkness. Second-round play suspended at 5:49 p.m. -

Cpc1.Chp:Corel VENTURA

The 2012 PGA Professional National Championship Players' Guide —1 q Bob Ackerman BOB ACKERMAN http://www.golfobserver.com/golfstats/golfstats.php?style=&tour=PGA&name=Bob+Ackerman&year=&tournament=PGA+Championship&in=SearPGA Championship Record ch Birth Date: March 27, 1953 Year Place To Par Score First Second Third Fourth Money 1985 CUT 7 149 77 72 0 0 $0.00 Birthplace: Benton Harbor, Mich. 1986 CUT 6 148 76 72 0 0 $0.00 Age: 59 1994 CUT 6 146 72 74 0 0 $0.00 Home: West Bloomfield, Mich. Ackerman’s Stats: College: Indiana ¢ PGA Championship’s Played In: .......... 3 ¢ Top 25 Finishes: ................................ 0 Turned Professional: 1975 ¢ Rounds Played In: .............................. 6 ¢ Rounds In 60s: .................................. 0 ¢ Cuts Made: ....................................... 0 ¢ Rounds Under Par: ............................ 0 PGA Membership: 1981 ¢ Scoring Average: .........................73.83 ¢ Rounds At Par: .................................. 0 ELIGIBILITY CODE: 5 ¢ Relation To Par: ............................... 19 ¢ Rounds Over Par: .............................. 6 ¢ Top 3 Finishes: .................................. 0 ¢ Lowest PGA Championship Score: ....72 PGA Classification: MP ¢ Top 5 Finishes: .................................. 0 ¢ Highest PGA Championship Score: ....77 PGA Section: Michigan ¢ Top 10 Finishes: ................................ 0 PGA Master Professional, golf clinician and owner of Bob Ack- erman Golf Academy in Commerce Township, Mich. … Winner, 1999 Chicago Open; 1989 Illinois -

'20-21 Misc Stats

2020-21 Korn Ferry Tour - Miscellaneous Stats Winner’s Scores # Event Winner R R R R4 TOT RTP Margin 1 2 3 1 The Bahamas Great Exuma Classic Tommy Gainey 66 75 67 69 277 -11 Four Strokes 2 The Bahamas Great Abaco Classic Jared Wolfe 67 69 65 69 270 -18 Four Strokes 3 Panama Championship Davis Riley 67 70 64 69 270 -10 One Stroke 4 Country Club de Bogota Championship Mito Pereira 65 66 68 64 263 -20 Two Strokes 5 LECOM Suncoast Classic Andrew Novak 69 64 66 66 265 -23 One Stroke 6 El Bosque Mexico Championship David Kocher 70 69 68 69 276 -12 Playoff 7 Korn Ferry Challenge at TPC Sawgrass Luke List 66 70 65 67 268 -12 One Stroke 8 The King & Bear Classic at World Golf Village Chris Kirk 66 65 64 67 262 -26 One Stroke 9 Utah Championship Kyle Jones 64 65 67 68 264 -20 Playoff 10 TPC Colorado Championship Will Zalatoris 67 67 70 69 273 -15 One Stroke 11 TPC San Antonio Challenge at the Canyons David Lipsky 69 66 62 66 263 -25 Four Strokes 12 TPC San Antonio Championship at the Oaks Davis Riley 70 69 66 67 272 -16 Two Strokes 13 Price Cutter Charity Championship Max McGreevy 64 68 71 64 267 -21 One Stroke 14 Pinnacle Bank Championship Seth Reeves 74 67 68 64 273 -11 One Stroke 15 WinCo Foods Portland Open Lee Hodges 70 64 68 71 273 -11 Two Strokes 16 Albertsons Boise Open Stephan Jaeger 65 64 65 68 262 -22 Two Strokes 17 Nationwide Children’s Hospital Championship Curtis Luck 68 66 68 71 273 -11 One Stroke 18 Korn Ferry Tour Championship Brandon Wu 67 69 69 65 270 -18 One Stroke 19 Lincoln Land Championship Brett Drewitt 67 62 68 68 265 -19 -

Controversy Behind Him, Weber Ready for U.S. Open by Jef Goodger MOORESVILLE, NC DIES at AGE 95 – After Last Year’S U.S

OCTOBER 17, 2019 CALIFORNIA 7502B Florence Ave, Downey,O CAWLING 90240 • Website: CaliforniaBowlingNews.com • Email: [email protected] N • Office:EWS (562) 807-3600 Fax: (562) 807-2288 PEARL KELLER, A PWBA & USBC HALL OF FAME MEMBER Controversy Behind Him, Weber Ready For U.S. Open by Jef Goodger MOORESVILLE, NC DIES AT AGE 95 – After last year’s U.S. ARLINGTON, Texas – Open, some might expect Pearl Keller, a Professional Pete Weber to have some Women’s Bowling Asso- pointed words entering this ciation and United States year’s event. Indeed, Weber Bowling Congress Hall has some biting words, but of Fame member, passed they are directed squarely away Oct. 2 in Brighton, at himself. Massachusetts, at age 95. “My competing on the She was inducted into PBA Tour the last cou- the PWBA Hall of Fame ple years has absolutely in 1997 in the Builder cat- sucked,” said Weber, a five- egory and two years later Pearl Keller time U.S. Open champion. joined the USBC Hall of more than 30 years. In “I’m not real happy about Fame for Meritorious Ser- 2001, WASA had a mem- that, so I’m trying to get vice. bership of 325 competitors myself into a little better Keller was a trailblaz- and awarded more than shape.” Pete Weber er for women’s bowling, $85,000 in 17 tournaments. During last year’s U.S. Congress, specifically cit- brushed off the question known. teaming with Jean Fish in Keller also paved the Open, Weber withdrew ing the practice schedules about practice, as his only “I’ve always liked the 1971 to start the Women’s way for women bowling early in qualifying and had prior to competition. -

Bob Ackerman Jason Alexander

The 2011 PGA Professional National Championship Players' Guide —1 q Bob Ackerman BOB ACKERMAN http://www.golfobserver.com/new/golfstats.php?style=&tour=PGA&name=Bob+Ackerman&year=&tournament=PGA+Championship&in=SearchPGA Championship Record Place After Rounds Birth Date: March 27, 1953x Year 1st 2nd 3rd Place To Par Score 1st 2nd 3rd 4th Money Birthplace: Benton Harbor, Mich. 1985 128 85 CUT +7 149 77 72 $1,000.00 Age: 58 1986 118 87 CUT +6 148 76 72 $1,000.00 Home: West Bloomfield, Mich. 1994 39 77 CUT +6 146 72 74 $1,200.00 College: Indiana Totals: Strokes+To Par Avg 1st 2nd 3rd 4th Money Turned Professional: 1975 443 + 73.83 75.0 72.7 0.0 0.0 $3,200.00 ¢ Ackerman has participated in three PGA Championships, playing six rounds of golf. He PGA Membership: 1981 has not made a cut. Rounds in 60s: none Rounds under par: none; Rounds at par: none; ELIGIBILITY CODE: 5 Rounds over par: six ¢ Lowest Score at PGA Championship: 72 PGA Classification: MP ¢ Highest Score at PGA Championship: 77 PGA Section: Michigan PGA Master Professional, golf clinician and owner of Bob Ack- erman Golf in Bloomfield, Mich. … Missed the cut in the 2010 PGA Professional National Championship … Tied for 11th in the 2004 Northern PGA Club Professional Championship … Four-time Illinois PGA Player of the Year (1985, ’87, ’88, ’89) … Winner, 1989 Illinois Open, Illinois PGA Championship (1988, ’92), Illinois PGA Match Play Championship (1984, ’87, ’88, ’89, ’96), 1984 PGA Senior-Junior Championship (with Bill Kozak), two PGA Tournament Series events (1980, ’81), 1975 and 2003 Michigan Open. -

JASON AICHELE COLIN AMARAL Birth Date: September 16, 1981 Birth Date: December 08, 1972 Birthplace: Richland, Wash

The 2014 PGA Professional National Championship Players' Guide —1 JASON AICHELE COLIN AMARAL Birth Date: September 16, 1981 Birth Date: December 08, 1972 Birthplace: Richland, Wash. Birthplace: Hamden, Conn. Age: 32 Age: 41 Home: Richland, Wash. Home: Port St. Lucie, Fla. College: University of Wyoming College: Georgia Southern Turned Professional: 2005 Turned Professional: 1993 PGA Membership: 2011 PGA Membership: 2001 ELIGIBILITY CODE: 5 ELIGIBILITY CODE: 5 PGA Classification: A-6 PGA Classification: A-8 PGA Section: Pacific Northwest PGA Section: Metropolitan Aichele (“Ike-Lee”) is a PGA teaching professional at Meadow PGA assistant professional at Metropolis Country Club in White Springs Country Club in Kennewick, Washington... Earned a Na- Plains, New York... Competed in National Championship five tional Championship berth by finishing fifth in the Pacific North- times, with best showing T-24 in 2008... Winner, 1997 Azores west PGA Championships... Finished third, 2008 Northwest Open in Portugal, 2004 International Club Professional Champi- Open; fifth, 2011 Washington State PGA Match Play Champion- onship, 2005 Duffys Rib Championship... Three-time winner on ship; fifth, 2010 Washington Open; third, 2008 Northwest Open... BAM tour... Winner, one event in 2006 in the PGA Tournament Played golf at the University of Wyoming, 2002-2005; competed Series; 2004 Met PGA Trieber Memorial... Winner, ‘01,’04 in every event... Caddied for current PGA Tour professional Westchester PGA Championship, 1999 Connecticut PGA Assis- David Hearn... Was 7th in 2004 NCAA Div. I for Fairways Hit... tants Championship... Finished fourth in 2005 National PGA As- Has recorded five holes-in-one, with one in competition... Also sistant Championship.. -

Cpc1.Chp:Corel VENTURA

KENT ABEGGLEN ELIGIBILITY CODE: 6 Residence: Washington, Utah Player Notes: Abegglen (“Ah-BEG-len”) is a PGA head professional at Sky Age: 47 Mountain Golf Course in Hurricane, Utah. Finished sixth in 2009 Utah Birth Date: March 14, 1963 PGA Section Championship. One of three PGA Professional brothers, Birthplace: Morgan, Utah joined by Kirk, a PGA teaching professional in Ogden, Utah, and Kris, a PGA head professional in Richfield, Utah. Learned to play golf through College: Weber State University (1984) the influence of his father, Ron, a former Weber State University men’s bas- Home Club: Sky Mountain Golf Course, Hurricane, Utah ketball coach, who guided the school to two NCAA Tournament appear- PGA Classification: A-1 ances and upset wins over Michigan State (1995) and North Carolina (1999) Turned Professional: 1987 during a 1989-99 term. Tied for first in professional division of 2004 Utah PGA Membership: 1991 Open, but overall title went to an amateur player. Lost playoff to compete PGA Section: Utah in first PGA Professional National Championship in 2002. Competed throughout his Section career with former National Champion Steve Schneiter, who is a distant relative. Winner, 1980 Utah Junior Open. Has recorded three holes-in-one, including one in competition. Personal: Wife, Joanne; Children: Jodi 25, Ryan 23, Kati 21, Bradley, 19, Michael, 9 Hobbies/Special Interests: Snow skiing, gardening, teaching golf He is participating in his first PGA Professional National Championship JOHN ABER ELIGIBILITY CODE: 5 Residence: Pittsburgh, Pa. Player Notes: PGA head professional at Allegheny Country Club in Age: 41 Sewickly, Pa. Tied for 8th in the 2006 PGA Professional National Cham- Birth Date: Aug. -

PLAYERS GUIDE — Salem Country Club | Peabody, Mass

38TH U.S. SENIOR OPEN CHAMPIONSHIP PLAYERS GUIDE — Salem Country Club | Peabody, Mass. — June 29-July 2, 2017 conducted by the 2017 U.S. SENIOR OPEN PLAYERS' GUIDE — 1 2017 U.S. Senior Open MICHAELhttp://www.golfstats.com/gs_scripts/golfstats/golfstats.php?guide=2017sopen&style=&tour=Champions&name=Michael+Allen&year=&tour ALLEN nament=&in=Search Exemption List (as of June 19) Birth Date: January 31, 1959 Michael Allen 9, 11, 18, 19 Tom Kite 19 Birthplace: San Mateo, Calif. Stephen Ames 19, 21, 22 Barry Lane 23 Billy Andrade 18, 19, 21, 22 Bernhard Langer 1, 2, 10, 11, 18, Age: 58 Ht.: 6’0" Wt.: 195 T. Armour III 18, 21 19, 21, 22 Magnus Atlevi 23 Tom Lehman 9, 11, 18, 19, 21, 22 Home: Scottsdale, Ariz. Woody Austin 17, 18, 19, 22, 25 Steve Lowery 19 College: Nevada Andre Bossert 23 a-Chip Lutz 13 Paul Broadhurst 10, 18, 22, 23 Jeff Maggert 1, 2, 18, 19, 22 Turned Professional: 1984 Olin Browne 1, 2, 18, 22 Prayad Marksaeng 24 Bart Bryant 18 Billy Mayfair 11, 19 Joined PGA Tour: 1990 Brad Bryant 1, 3 Scott McCarron 18, 21, 22 Tom Byrum 18 a-Mike McCoy 16 Joined Champions Tour: 2009 M. Calcavecchia 19, 22 Rocco Mediate 9, 18, 19, 22 Championshttp://www.golfstats.com/gs_scripts/golfstats/golfstats.php?guide=2017sopen&stat=31&name=Michael+Allen&tour=Champions Tour Playoff Record: 2-2 Roger Chapman 1, 2, 9 C. Montgomerie 1, 2, 9, 11, 18, 22 Fred Couples 19, 21, 22 Gil Morgan 19 Champions Tour Victories: 8 - 2009 Senior PGA John Cook 19 Mark O’Meara 19 Championship; 2012 Encompass Insurance Pro-Am, Liberty John Daly 21 Jesper Parnevik 18, 19, 22 Mutual Legends of Golf; 2013 Mississippi Gulf Resort Classic, Marco Dawson 10, 22 Corey Pavin 19, 26 Allen Doyle 3 Tom Pernice Jr. -

'20-21 Misc Stats

2020-21 Korn Ferry Tour - Miscellaneous Stats Winner’s Scores # Event Winner R R R R4 TOT RTP Margin 1 2 3 1 The Bahamas Great Exuma Classic Tommy Gainey 66 75 67 69 277 -11 Four Strokes 2 The Bahamas Great Abaco Classic Jared Wolfe 67 69 65 69 270 -18 Four Strokes 3 Panama Championship Davis Riley 67 70 64 69 270 -10 One Stroke 4 Country Club de Bogota Championship Mito Pereira 65 66 68 64 263 -20 Two Strokes 5 LECOM Suncoast Classic Andrew Novak 69 64 66 66 265 -23 One Stroke 6 El Bosque Mexico Championship David Kocher 70 69 68 69 276 -12 Playoff 7 Korn Ferry Challenge at TPC Sawgrass Luke List 66 70 65 67 268 -12 One Stroke 8 The King & Bear Classic at World Golf Village Chris Kirk 66 65 64 67 262 -26 One Stroke 9 Utah Championship Kyle Jones 64 65 67 68 264 -20 Playoff 10 TPC Colorado Championship Will Zalatoris 67 67 70 69 273 -15 One Stroke 11 TPC San Antonio Challenge at the Canyons David Lipsky 69 66 62 66 263 -25 Four Strokes 12 TPC San Antonio Championship at the Oaks Davis Riley 70 69 66 67 272 -16 Two Strokes 13 Price Cutter Charity Championship Max McGreevy 64 68 71 64 267 -21 One Stroke 14 Pinnacle Bank Championship Seth Reeves 74 67 68 64 273 -11 One Stroke 15 WinCo Foods Portland Open Lee Hodges 70 64 68 71 273 -11 Two Strokes 16 Albertsons Boise Open Stephan Jaeger 65 64 65 68 262 -22 Two Strokes 17 Nationwide Children’s Hospital Championship Curtis Luck 68 66 68 71 273 -11 One Stroke 18 Korn Ferry Tour Championship Brandon Wu 67 69 69 65 270 -18 One Stroke 19 Lincoln Land Championship Brett Drewitt 67 62 68 68 265 -19 -

2017-18 Texas Golf Fact Book

TEXAS GOLF 2017-18 Texas Golf Fact Book 2017-18 LONGHORNS COACHES & STAFF MEDIA/PROGRAM INFORMATION Bring, Christoffer __________________5 Head Coach John Fields ___________ 10-12 2017-18 Roster ______________________2 Carter, Cash_______________________5 Assistant Coach Jean-Paul Hebert ______12 2017-18 Schedule ____________________2 Chervony, Steven __________________3 Volunteer Coach Richie Coughlan ______13 Pronunciation Guide ________________ 2 Costello, Nick _____________________3 Ghim, Doug ____________________ 4-5 HISTORY & HONORS YEAR IN REVIEW Jones, Drew ______________________6 Scheffler, Scottie _________________ 8-9 All-Time Tournament Results ______ 22-25 2016-17 Statistics ___________________14 Sexton, Parker _____________________6 All-Time NCAA Championship Results 26-27 2016-17 Individual Results ____________15 Soosman, Spencer _________________7 All-Time Tournament Medalists _______28 2016-17 Head-to-Head Results ________16 All-Time Team Bests _________________29 2016-17 Miscellaneous Statistics _______16 Longhorns on the PGA Tour _______ 30-32 2016-17 Tournament Results _______ 17-21 Longhorn PGA Tour Winners __________33 All-Americans & National Honors ___ 34-35 Conference Honors ______________ 36-38 All-Time Conference Standings _____ 39-40 Conference Championship Teams _____41 T-Association/Letterwinners _______ 42-43 Quick Facts TEXAS GOLF QUICK FACTS MEDIA RELATIONS INFO/GOLF 2016-17 Big 12 Finish __________________________________ 1st Susie Epp __________________Assistant Media Relations Director NCAA Championships -

2013-14 Texas Golf Fact Book Quick Facts

TEXAS GOLF 2013-14 Texas Golf Fact Book 2013-14 LONGHORNS 4 COACHES & STAFF 10 MEDIA/PROGRAM INFORMATION 1 2013-14 Longhorns: Head Coach John Fields ______________10-11 2013-14 Roster _______________________ 2 Funk, Taylor _______________________ 4 Assistant Coach Ryan Murphy ___________ 12 2013-14 Schedule _____________________ 2 Griffin, Will _______________________ 4 Volunteer Assistant Coach 2013-14 TV/Radio Lineup _______ Back cover Hakula, Toni _______________________ 5 Jean-Paul Hebert __________________ 12 Media Information & Policies ___________ 3 Hall, Gavin ________________________ 6 Pronunciation Guide __________________ 2 Hickok, Kramer _____________________ 6 HISTORY & HONORS 19 Quick Facts _________________________ 1 Hossler, Beau ______________________ 7 McCarthy, Brax _____________________ 7 All-Americans & National Honors ______30-31 YEAR IN REVIEW 13 Preus, Kalena ______________________ 8 All-Time Conference Championship Results _____ 34 Schnitzer, Johnathan _______________ 8-9 All-Time Conference Standings ________35-36 2012-13 Statistics _____________________ 13 Termeer, Tayler _____________________ 9 All-Time Team Bests __________________ 27 2012-13 Head-to-Head Results ___________ 15 All-Time NCAA Championship Results ___22-23 2012-13 Miscellaneous Statistics __________ 15 All-Time Team Bests __________________ 27 2012-13 Individual Results ______________ 14 All-Time Tournament Results _________19-21 2012-13 Tournament Results __________16-18 Morris Williams Intercollegiate ________25-26 Conference Honors _________________32-34 -

11Srs1.Chp:Corel VENTURA

The 75th Senior PGA Championship Players' Guide —1 Michael Allen MICHAELhttp://www.golfstats.com/gs_scripts/golfstats/golfstats.php?guide=2014SRPGA&style=&tour=Champions&name=Michael+Allen&year=&tour ALLEN nament=&in=Search Yearly PGA Tour Statistics/Rank Birth Date: January 31, 1959 Year Starts Cuts Made Top-10s Wins Scoring Avg./Rank Money/Rank 1992http://www.golfstats.com/gs_scripts/golfstats/golfstats.php?guide=2014SRPGA&style=&tour=PGA&name=Michael+Allen&year=1992&tourna 16 4 0 0 0.00ment=&in=Search $11,455.00 (233) Birthplace: San Mateo, Calif. 1993http://www.golfstats.com/gs_scripts/golfstats/golfstats.php?guide=2014SRPGA&style=&tour=PGA&name=Michael+Allen&year=1993&tourna 27 15 3 0 71.10 (76)ment=&in=Search $231,072.00 (73) Age: 55 Ht.: 6’0" Wt.: 195 1994http://www.golfstats.com/gs_scripts/golfstats/golfstats.php?guide=2014SRPGA&style=&tour=PGA&name=Michael+Allen&year=1994&tourna 32 17 0 0 71.67 (137)ment=&in=Search $91,191.00 (162) 1995http://www.golfstats.com/gs_scripts/golfstats/golfstats.php?guide=2014SRPGA&style=&tour=PGA&name=Michael+Allen&year=1995&tourna 21 7 1 0 71.85 (153)ment=&in=Search $55,825.00 (197) Home: Scottsdale, Ariz. 1996http://www.golfstats.com/gs_scripts/golfstats/golfstats.php?guide=2014SRPGA&style=&tour=PGA&name=Michael+Allen&year=1996&tourna 1 1 0 0 0.00ment=&in=Search $2,425.00 (362) 2000http://www.golfstats.com/gs_scripts/golfstats/golfstats.php?guide=2014SRPGA&style=&tour=PGA&name=Michael+Allen&year=2000&tourna 1 1 0 0 0.00ment=&in=Search $4,936.00 (343) College: Nevada 2001http://www.golfstats.com/gs_scripts/golfstats/golfstats.php?guide=2014SRPGA&style=&tour=PGA&name=Michael+Allen&year=2001&tourna