Understanding the Determinants of Homelessness Through Examining

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EDUCATION of POOR GIRLS in NORTH WEST ENGLAND C1780 to 1860: a STUDY of WARRINGTON and CHESTER by Joyce Valerie Ireland

EDUCATION OF POOR GIRLS IN NORTH WEST ENGLAND c1780 to 1860: A STUDY OF WARRINGTON AND CHESTER by Joyce Valerie Ireland A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy at the University of Central Lancashire September 2005 EDUCATION OF POOR GIRLS IN NORTH WEST ENGLAND cll8Oto 1860 A STUDY OF WARRINGTON AND CHESTER ABSTRACT This study is an attempt to discover what provision there was in North West England in the early nineteenth century for the education of poor girls, using a comparative study of two towns, Warrington and Chester. The existing literature reviewed is quite extensive on the education of the poor generally but there is little that refers specifically to girls. Some of it was useful as background and provided a national framework. In order to describe the context for the study a brief account of early provision for the poor is included. A number of the schools existing in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries continued into the nineteenth and occasionally even into the twentieth centuries and their records became the source material for this study. The eighteenth century and the early nineteenth century were marked by fluctuating fortunes in education, and there was a flurry of activity to revive the schools in both towns in the early nineteenth century. The local archives in the Chester/Cheshire Record Office contain minute books, account books and visitors' books for the Chester Blue Girls' school, Sunday and Working schools, the latter consolidated into one girls' school in 1816, all covering much of the nineteenth century. -

Birchwood Warrington, WA3 7PB

K2 Birchwood Warrington, WA3 7PB Birchwood TO LET 50,549 sq ft Self-contained HQ office premises K2 boasts 50,549 sq ft of office space, located in Birchwood, one of the North West’s premier business locations. Well specified, open plan offices K2 Kelvin Close is modern self- contained HQ office building providing two-storey office accommodation constructed to a high standard, with extensive on-site parking. The building will undergo a full refurbishment to provide open plan, Grade A offices, arranged over ground and one upper floor with modern feature reception and an impressive central glazed atrium, providing good levels of natural light. Illustrative Specification 15 minutes to Three million people Manchester and within a half an hour 27 minutes to drive time - the largest Liverpool by train workforce catchment in the UK outside London. row B 4 d y 7 a th i 5 o m A R S M6 e n r Cross u L N a ew n o 9 Lane e b 4 J11 l location o A ane G L orth M62 3 w th 7 Sou 5 TO MANCHESTER A e TO PRESTON ton Lan Myddle Strategically located within Birchwood, one of the most successful & THE NORTH 4 7 D Kelvin 5 e A lp Close business locations in the North West, the property isWINWICK accessed via h Kelvin Close, off the main Birchwood Park Avenue. L Kelvin Close a 9 ne Birchwood Bus Stop A4 Golf Course The property is extremely well situated, at the heart of the North Birchwood y West motorway network, close to junctions 21/21a of the M6 RISLEY a W J21a M Park d 9 i l Avenue o and junctions 10 and 11 of the M62. -

Warrington Guardian 12.7.68)

WHAT’S IN A NAME? (Warrington Guardian 12.7.68) 23, WOOLSTON WOOLSTON – WITH – MARTINSCROFT is a joint township on the high road from Warrington to Manchester: this high road is one of the oldest in Lancashire. Only four roads were shown in Lancashire in 1675 in Ogilby’s ‘’Britannia’’ and the Warrington to Manchester road was one of the four. This became a turnpike road in the 18th century when slag from the Warrington Copper Works was used in it’s construction. Unfortunately the course of this road appears to have been little changed since then in spite of heavy traffic, considerably increased in recent years by placing on it an access point to the M6 at the Woolston end of the Thelwall Viaduct. Clearly it would have been in the best interest of all concerned if this old road had been straightened and widened at Woolston before the recent rapid urban development there had been permitted to take place. For centuries after the Norman Conquest, Woolston was a tiny backwater, remote even from neighbouring Warrington to which it was connected by an early and primitive road. Communication also existed between Woolston and Thelwall by means of a ferry across the River Mersey until suddenly in the 18th century, Woolston found itself connected to Warrington and Manchester not only by a turnpike road, but also by a short canal constructed as part of an early river navigation scheme designed to eliminate the long bends in the river in its course from Warrington eastwards. New Cut The first Woolston Cut was made about 1720 and less than a century later this was replaced by the Woolston New Cut. -

Mersey Estuary Catchment Flood Management Plan Summary Report December 2009 Managing Flood Risk We Are the Environment Agency

Mersey Estuary Catchment Flood Management Plan Summary Report December 2009 managing flood risk We are the Environment Agency. It’s our job to look after your environment and make it a better place – for you, and for future generations. Your environment is the air you breathe, the water you drink and the ground you walk on. Working with business, Government and society as a whole, we are making your environment cleaner and healthier. The Environment Agency. Out there, making your environment a better place. Published by: Environment Agency Richard Fairclough House Knutsford Road Warrington WA4 1HT Tel: 0870 8506506 Email: [email protected] www.environment-agency.gov.uk © Environment Agency All rights reserved. This document may be reproduced with prior permission of the Environment Agency. December 2009 Introduction I am pleased to introduce our summary of the Mersey Estuary Catchment Flood Management Plan (CFMP). This CFMP gives an overview of the flood risk in the Mersey Estuary catchment and sets out our preferred plan for sustainable flood risk management over the next 50 to 100 years. The Mersey Estuary CFMP is one of 77 CFMPs for have a 1% chance of flooding in any one year from rivers England and Wales. Through the CFMPs, we have (i.e. a 1% annual probability). We estimate that by 2100 assessed inland flood risk across all of England and approximately 25,000 properties will be at risk of river Wales for the first time. The CFMP considers all types of flooding. This is a 30% increase compared to the current inland flooding, from rivers, groundwater, surface water number at risk across the catchment. -

NRT Index Stations

Network Rail Timetable OFFICIAL# May 2021 Station Index Station Table(s) A Abbey Wood T052, T200, T201 Aber T130 Abercynon T130 Aberdare T130 Aberdeen T026, T051, T065, T229, T240 Aberdour T242 Aberdovey T076 Abererch T076 Abergavenny T131 Abergele & Pensarn T081 Aberystwyth T076 Accrington T041, T097 Achanalt T239 Achnasheen T239 Achnashellach T239 Acklington T048 Acle T015 Acocks Green T071 Acton Bridge T091 Acton Central T059 Acton Main Line T117 Adderley Park T068 Addiewell T224 Addlestone T149 Adisham T212 Adlington (cheshire) T084 Adlington (lancashire) T082 Adwick T029, T031 Aigburth T103 Ainsdale T103 Aintree T105 Airbles T225 Airdrie T226 Albany Park T200 Albrighton T074 Alderley Edge T082, T084 Aldermaston T116 Aldershot T149, T155 Aldrington T188 Alexandra Palace T024 Alexandra Parade T226 Alexandria T226 Alfreton T034, T049, T053 Allens West T044 Alloa T230 Alness T239 Alnmouth For Alnwick T026, T048, T051 Alresford (essex) T011 Alsager T050, T067 Althorne T006 Page 1 of 53 Network Rail Timetable OFFICIAL# May 2021 Station Index Station Table(s) Althorpe T029 A Altnabreac T239 Alton T155 Altrincham T088 Alvechurch T069 Ambergate T056 Amberley T186 Amersham T114 Ammanford T129 Ancaster T019 Anderston T225, T226 Andover T160 Anerley T177, T178 Angmering T186, T188 Annan T216 Anniesland T226, T232 Ansdell & Fairhaven T097 Apperley Bridge T036, T037 Appleby T042 Appledore (kent) T192 Appleford T116 Appley Bridge T082 Apsley T066 Arbroath T026, T051, T229 Ardgay T239 Ardlui T227 Ardrossan Harbour T221 Ardrossan South Beach T221 -

LPB Board Papers 10.05.21

Libraries Partnership Board Agenda Monday 10th May 2021, 1.00pm till 2.30pm Online meeting using Microsoft Teams 1. Welcome and apologies LG 2.00 - 2.05 2. Meeting etiquette LG 2.05 – 2.06 3. Minutes and matters arising from last LG 2.06 – 2.10 meeting (Enclosed) 4. COVID Recovery EH / CS 2.10 – 2.20 5. Central Library Roof refurbishment EB 2.20 -2.25 5. Building refurbishment updates EB 2.25 – 2.50 7. Terms of Reference EB 3.05 – 3.15 8. Contributions from the public gallery All 3.15 – 3.25 9. A.O.B All 3.25 - 3.30 Libraries Partnership Board Meeting Monday 8th February 2021, 2.00pm till 3.00pm Online meeting using Microsoft Teams Meeting Minutes In attendance: Members Lynton Green – WBC – Deputy Chief Executive and Director of Corporate Services Eleanor Blackburn – WBC – Head of Inclusive Growth and Partnerships Cheryl Siddall – Livewire and Culture Warrington, People, Performance and Resources Director Cllr. Joan Grime – Friends of Culcheth Library Peter Lewenz – SWISH Board Support Garry D’Arcy (GD) – WBC, Partnership and Commissioning Officer Actions 1. Welcome and apologies Apologies received from 2. Meeting etiquette • LG talked to the group about meeting etiquette and how Microsoft teams works as well as how to interact in the meeting. 3. Minutes and Matters Arising • CS clarified from the previous minutes that LiveWire have a volunteer policy in place with a number of documents that supported this. • After discussion it was agreed that the volunteer policy would be taken to the next meeting of the Friends of groups to explain the voluntary policy and reassure that volunteering does not take away library staff roles. -

A History of the University of Manchester Since 1951

Pullan2004jkt 10/2/03 2:43 PM Page 1 University ofManchester A history ofthe HIS IS THE SECOND VOLUME of a history of the University of Manchester since 1951. It spans seventeen critical years in T which public funding was contracting, student grants were diminishing, instructions from the government and the University Grants Commission were multiplying, and universities feared for their reputation in the public eye. It provides a frank account of the University’s struggle against these difficulties and its efforts to prove the value of university education to society and the economy. This volume describes and analyses not only academic developments and changes in the structure and finances of the University, but the opinions and social and political lives of the staff and their students as well. It also examines the controversies of the 1970s and 1980s over such issues as feminism, free speech, ethical investment, academic freedom and the quest for efficient management. The author draws on official records, staff and student newspapers, and personal interviews with people who experienced the University in very 1973–90 different ways. With its wide range of academic interests and large student population, the University of Manchester was the biggest unitary university in the country, and its history illustrates the problems faced by almost all British universities. The book will appeal to past and present staff of the University and its alumni, and to anyone interested in the debates surrounding higher with MicheleAbendstern Brian Pullan education in the late twentieth century. A history of the University of Manchester 1951–73 by Brian Pullan with Michele Abendstern is also available from Manchester University Press. -

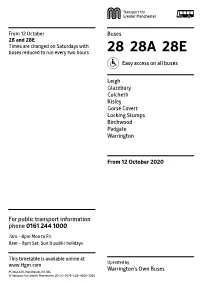

28 28A 28E Easy Access on All Buses

From 12 October Buses 28 and 28E Times are changed on Saturdays with buses reduced to run every two hours 28 28A 28E Easy access on all buses Leigh Glazebury Culcheth Risley Gorse Covert Locking Stumps Birchwood Padgate Warrington From 12 October 2020 For public transport information phone 0161 244 1000 7am – 8pm Mon to Fri 8am – 8pm Sat, Sun & public holidays This timetable is available online at Operated by www.tfgm.com Warrington’s Own Buses PO Box 429, Manchester, M1 3BG ©Transport for Greater Manchester 20–SC–0578–G28–4500–1020 Additional information Alternative format Operator details To ask for leaflets to be sent to you, or to request Warrington’s Own Buses large print, Braille or recorded information Wilderspool Causeway, Warrington, phone 0161 244 1000 or visit www.tfgm.com Cheshire, WA4 6PT Telephone 01925 634296 Easy access on buses Journeys run with low floor buses have no Travelshops steps at the entrance, making getting on Leigh Bus Station and off easier. Where shown, low floor Monday to Friday 7am to 5.30pm buses have a ramp for access and a dedicated Saturday 8.30am to 1.15pm and 2pm to 4pm space for wheelchairs and pushchairs inside the Sunday* Closed bus. The bus operator will always try to provide *Including public holidays easy access services where these services are scheduled to run. Using this timetable Timetables show the direction of travel, bus numbers and the days of the week. Main stops on the route are listed on the left. Where no time is shown against a particular stop, the bus does not stop there on that journey. -

![THE LONDON GAZETTE, 9 MARCH, ]9I8](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9306/the-london-gazette-9-march-9i8-2019306.webp)

THE LONDON GAZETTE, 9 MARCH, ]9I8

1692 THE LONDON GAZETTE, 9 MARCH, ]9i8. Electricity Commission.—1928. Back Lane, from the Winwick Pumping Station, in a south-westerly direction for WARRINGTON ELECTRICITY a distance of 300 yards or thereabouts. Winwick Road, from St. Oswald's (EXTENSION). Church, in a southerly direction for a dis- (Supply o!f Electricity by the Warrington tance of 200 yards or thereabouts. Corporation in the Parishes of Winwick- Newton Road, from its junction with with-Hulme; Houghton, Middleton and Cotton Street, in a northerly direction for Arbury; South worth-with-Croft; Poulton- a distance of 100 yards or thereabouts. with-Fearnhead; and Woolston-with-Mar- Cotton Street, from Hermitage Lane tinscroffc, in the Bural District of Warring- to Newton Road. ton, in the County Palatine of Lancaster, Hallfields Road, from Orford Green to and the Parishes of Acton Grange; Moore; the Borough Boundary. Daresbury; Hatton; and Stretton; in the Orford Green, from School Lane to Orford Road. Rural District of Euncorn, in the County Long Lane, from the School in a of Chester.) westerly direction, for a distance of 230 FflHE Mayor, Aldermen and Burgesses of yards or thereabouts. -•- the Borough of Warrington (hereinafter School Road, from Orford Green in a called " the Corporation "), whose address is northerly direction for a distance of 400 The Town Clerk's Office, Warrington, hereby yards or thereabouts. give notice that they intend to apply to the Birtles Road, from School Road to Electricity Commissioners under the Elec- Orford Road. tricity (Supply) Acts, 1882 to 1926, for a Orford Road, from Orford Green in an Special Order (hereinafter called " the easterly direction, turning southwards for Order ") for the following objects (namely):— a distance of 200 yards or thereabouts. -

How to Accommodate Forcast Growth on the Cheshire Line Corridor

How to accommodate forecast growth on the Cheshire Line Committee (CLC) corridor? Railway investment choices October 2019 02 Contents Part A: Executive Summary 03 Part B: The Long Term Planning Process and Continuous 05 Modular Strategic Planning Part C: Today’s Railway 07 Part D: Factors influencing change 13 Part E: Impact of future year growth 16 Part F: Approach to option development 19 Part G: Emerging Strategic Advice 22 Part H: Options and Advice to Funders 24 How to accommodate forecast growth on the Cheshire Line Committee (CLC) corridor? October 2019 03 Part A Executive Summary We are pleased to present an assessment of some current network assets, whilst accommodating the possible investment choices for the Cheshire Lines franchise commitments using both the CLC route and Committee (CLC) corridor between Liverpool and elsewhere. Network Rail has worked collaboratively Manchester via Warrington Central. These choices are with rail industry colleagues to consider the presented to understand which interventions may be investment choices that may be required to support required to meet future growth forecasts on the CLC this forecast growth between 2024 and 2043. corridor by 2026, 2033 and 2043. This work has been Since the development of the original report, the completed as part of the Continuous Modular economic appraisal results have been updated to Strategic Planning (CMSP) approach adopted under reflect some alternative assumptions on capital and the Long-Term Planning Process (LTPP). Industry operating costs. Whilst these revisions have improved partners have participated in the study. This the results, the updated value for money assessment collaborative approach has helped to identify some is still not sufficient to demonstrate a ‘good’ case (with possible investment choices to accommodate forecast a benefit cost ratio above 2.0). -

Cheshire Area Rail Services

Merseyrail Merseyrail Northern Rail Northern Rail Virgin Trains Northern Rail Transpennine Express Northern Rail Metrolink Northern Rail Transpennine to Southport to Ormskirk to Wigan to Wigan, Preston, Blackpool to Preston, Carlisle, to Wigan,Kirby to Scotland, to Blackburn to Bury to Bradford Leeds, Selby Express Glasgow,Edinburgh Southport Lake District The North to Leeds, Marsden Scarborough M Seaforth Aintree North East M Garswood & Litherland M Swinton Greenfield Kirkby St Helens Central M Mossley Bootle MOrrell M Salford Ashton-under Park Manchester M New Strand Thatto Heath Salford Central Victoria -Lyne Fazakerley M Crescent Stalybridge M Eccleston ParkM M Bootle Walton M M Oriel Road Rice Lane MPrescot M M Lea M Newton-le M Guide Whiston Green -Willows Patricroft Eccles Ardwick Ashburys Gorton Fairfield Earlestown ManchesterOxford Rd M M Huyton Deansgate Bridge New Flowery Field Brighton MBank Hall Kirkdale Rainhill St Helens M M Roby Eccles Manchester Belle Newton for Hyde M Junction M Wallasey Piccadilly Vue Hyde Ryder North Grove Rd M M Media City Godley M Broad Brow M M Sandhills Green Hyde Hattersley M Wallasey M Wavertree Trafford LiverpoolM Reddish Central Village Technology Park Park Broadbottom South North M Lime M Warrington Humphrey Levenshulme M Moorfields Parkway Mauldeth Hadfield St M Central Park Rd Woodley Merseyrail M Bidston BirkenheadConway Park ParkBirkenhead Brinnington to Hoylake/West Kirby Birkenhead North Hamilton Sq Urmston Heaton Dinting Burnage Moreton Leasowe Chapel Bredbury Birkenhead HuntsHalewood Hough -

NHS England Cheshire and Merseyside: Lots and Locations

NHS England Cheshire and Merseyside: Lots and locations Local Proposed Lot names Related wards Related post codes Authority / Location of (including but not provider exclusively) Cheshire Cheshire East (East) Alderley Edge, Bollington, Chelford, Congleton, CW4, CW12, SK9, SK10, East Disley, Handforth, Holmes Chapel, Knutsford, SK11, SK12, WA16 Macclesfield, Mobberley, Poynton, Prestbury, Wilmslow Cheshire East (South) Alsagar, Audlem, Crewe, Middlewich, Nantwich, CW1, CW2, CW5, CW10, Sandbach, Scholar Green, Wrenbury CW11, ST7 Cheshire Cheshire West & Barnton, Lostock Gralam, Northwich, Sandiway, CW7, CW8, CW9 West and Chester (East) Weaverham, Winsford Chester Cheshire West & Chester, Farndon, Malpas, Tarvin, Tattenhall, CH1, CH2, CH3, CH4, (includes Chester (West) Kelsall, Bunbury, Tarporley, Frodsham, Helsby, CW6, SY14, WA6 Vale Royal) Ellesmere Port, Neston, Great Sutton, Little Sutton, Neston, Elton, Willaston Halton Halton Hough Green, Runcorn, Widnes WA7,WA8 Knowsley - Halewood, Huyton, Kirkby, Stockbridge Village, L14, L25, L26, L28, L32, Whiston L33, L34, L35, L36 Liverpool Liverpool North Aintree, Warbreck, Fazakerley, Croxteth, L4, L5, L9, L10, L11, L13 Clubmoor, Norris Green, Kirkdale, Anfield, (Clubmoor) Everton, Walton Liverpool South Riverside, Toxteth, Prince’s Park, Greenbank, L1 (Riverside), L8,L12 Church, Woolton, St Michaels', Mossley Hill, (Greenbank),L17, L18, Aigburth, Cressington, Allerton, Hunts Cross, L19, L24, L25 Speke, Garston, Gatacre Liverpool East Central, Dovecot, Kensington, Fairfield, Tuebrook, L1 (Central),