The Swedish Riksdag As Scrutiniser of the Principle of Subsidiarity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Synopsis of the Meeting Held in Strasbourg on 21 January 2013

BUREAU OF THE ASSEMBLY AS/Bur/CB (2013) 01 21 January 2013 TO THE MEMBERS OF THE ASSEMBLY Synopsis of the meeting held in Strasbourg on 21 January 2013 The Bureau of the Assembly, meeting on 21 January 2013 in Strasbourg, with Mr Jean-Claude Mignon, President of the Assembly, in the Chair, as regards: - First part-session of 2013 (Strasbourg, 21-25 January 2013): i. Requests for debates under urgent procedure and current affairs debates: . decided to propose to the Assembly to hold a debate under urgent procedure on “Migration and asylum: mounting tensions in the Eastern Mediterranean” on Thursday 24 January 2013 and to refer this item to the Committee on Migration, Refugees and Displaced Persons for report; . decided to propose to the Assembly to hold the debate under urgent procedure on “Recent developments in Mali and Algeria and the threat to security and human rights in the Mediterranean region” on Thursday 24 January 2013 and to refer this item to the Committee on Political Affairs and Democracy for report; . decided not to hold a current affairs debate on “The deteriorating situation in Georgia”; . took note of the decision by the UEL Group to withdraw its request for a current affairs debate on “Political developments in Turkey regarding the human rights of the Kurds and other minorities”; ii. Draft agenda: updated the draft agenda; - Progress report of the Bureau of the Assembly and of the Standing Committee (5 October 2012 – 21 January 2013): (Rapporteur: Mr Kox, Netherlands, UEL): approved the Progress report; - Election observation: i. Presidential election in Armenia (18 February 2013): took note of the press release issued by the pre-electoral mission (Yerevan, 15-18 January 2013) and approved the final composition of the ad hoc committee to observe these elections (Appendix 1); ii. -

Spotlight on Parliaments in Europe

Spotlight on Parliaments in Europe Issued by the EP Directorate for Relations with National Parliaments N° 13 - November 2016 Quality of legislation stemming from the EU On 19 September 2016, the Italian Senate submitted a request to the ECPRD network concerning the quality of legislation stemming from the EU. This request was an opportunity for National Parliaments to exchange best practices on how to ensure the quality of legislation with specific regard to transposition, implementation and enforcement of EU law. From the 21 answers provided by National Parliaments it is clear that transposition and implementation of EU Law is highly unlikely to require special attention. While almost all of them are using legislative guidelines and procedures for guaranteeing high standard of general law-making, only a few have felt the need to establish special mechanisms to ensure the quality of legislation stemming from the EU. The use of legislative guidelines and procedures; the main way to ensure the quality of legislation stemming from the EU. The use of legislative guidelines and procedures appears to be the most common way for National Parliaments to ensure the quality of legislation, also the legislation stemming from the EU. It allows for good linguistic coherence in the national languages while enhancing the standardization of the law. For example, in the case of Austria, the Federal Chancellery has published specific “Legistische Richtlinien”. In Spain, the instrument used is the Regulation Guidelines adopted in the Agreement of the Council of Ministers of 22 July 2005. Both Italian Chambers use Joint Guidelines on drafting of national legislation. -

How Sweden Is Governed Content

How Sweden is governed Content The Government and the Government Offices 3 The Prime Minister and the other ministers 3 The Swedish Government at work 3 The Government Offices at work 4 Activities of the Government Offices 4 Government agencies 7 The budget process 7 The legislative process 7 The Swedish social model 9 A democratic system with free elections 9 The Swedish administrative model – three levels 10 The Swedish Constitution 10 Human rights 11 Gender equality 11 Public access 12 Ombudsmen 12 Scrutiny of the State 13 Sweden in the world 14 Sweden and the EU 14 Sweden and the United Nations 14 Nordic cooperation 15 Facts about Sweden 16 Contact 16 2 HOW SWEDEN IS GOVERNED The Government and the Government Offices The Prime Minister and the other ministers After each election the Speaker of the Riksdag (the Swedish Parliament) submits a proposal for a new Prime Minister. The Prime Minister is subsequently appoin ted by the Riksdag and tasked with forming a government. The Government, led by the Prime Minister, governs Sweden. The Government consists of the Prime Minister and a number of ministers, each with their own area of responsibility. The Swedish Government at work The Government governs Sweden and is the driving force in the process by which laws are created and amended, thereby influencing the development of society as a whole. However, the Government is accountable to the Riksdag and must have its support to be able to implement its policies. The Government governs the country, which includes: • submitting legislative proposals to the Riksdag; • implementing decisions taken by the Riksdag; • exercising responsibility for the budget approved by the Riksdag; • representing Sweden in the EU; • entering into agreements with other states; • directing central government activities; • taking decisions in certain administrative matters not covered by other agencies. -

The Parliamentary Mandate

THE PARLIAMENTARY MANDATE A GLOBAL COMPARATIVE STUDY THE PARLIAMENTARY MANDATE A GLOBAL COMPARATIVE STUDY Marc Van der Hulst Inter-Parliamentary Union Geneva 2000 @ Inter-Parliamentary Union 2000 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the Inter-Parliamentary Union. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not be a way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold hired or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form or binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent publisher. ISBN 92-9142-056-5 Published by INTER-PARLIAMETARY UNION Headquarters Liaison Office with the United Nations Place du Petit-Saconnex 821 United Nations Plaza C.P. 438 9th Floor 1211 Geneva 19 New York, N.Y. 10017 Switzerland United States of America Layout, printing and binding by Atar, Geneva Cover design by Aloys Robellaz, Les Studios Lolos, Carouge, Switzerland (Translated from the French by Jennifer Lorenzi and Patricia Deane) t Table of Contents FOREWORD ix ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS xi INTRODUCTION l PART ONE: NATURE AND DURATION OF THE PARLIAMENTARY MANDATE I. NATURE OF THE PARLIAMENTARY MANDATE 6 1. The traditional opposition between national sovereignty and popular sovereignty 6 2. The free representational mandate 8 3. The imperative mandate 9 4. A choice motivated by pragmatic rather than ideological considerations? 10 II. DURATION OF THE PARLIAMENTARY MANDATE.. -

List of Participants Liste Des Participants

LIST OF PARTICIPANTS LISTE DES PARTICIPANTS 142nd IPU Assembly and Related Meetings (virtual) 24 to 27 May 2021 - 2 - Mr./M. Duarte Pacheco President of the Inter-Parliamentary Union Président de l'Union interparlementaire Mr./M. Martin Chungong Secretary General of the Inter-Parliamentary Union Secrétaire général de l'Union interparlementaire - 3 - I. MEMBERS - MEMBRES AFGHANISTAN RAHMANI, Mir Rahman (Mr.) Speaker of the House of the People Leader of the delegation EZEDYAR, Mohammad Alam (Mr.) Deputy Speaker of the House of Elders KAROKHAIL, Shinkai (Ms.) Member of the House of the People ATTIQ, Ramin (Mr.) Member of the House of the People REZAIE, Shahgul (Ms.) Member of the House of the People ISHCHY, Baktash (Mr.) Member of the House of the People BALOOCH, Mohammad Nadir (Mr.) Member of the House of Elders HASHIMI, S. Safiullah (Mr.) Member of the House of Elders ARYUBI, Abdul Qader (Mr.) Secretary General, House of the People Member of the ASGP NASARY, Abdul Muqtader (Mr.) Secretary General, House of Elders Member of the ASGP HASSAS, Pamir (Mr.) Acting Director of Relations to IPU Secretary to the delegation ALGERIA - ALGERIE GOUDJIL, Salah (M.) Président du Conseil de la Nation Président du Groupe, Chef de la délégation BOUZEKRI, Hamid (M.) Vice-Président du Conseil de la Nation (RND) BENBADIS, Fawzia (Mme) Membre du Conseil de la Nation Comité sur les questions relatives au Moyen-Orient KHARCHI, Ahmed (M.) Membre du Conseil de la Nation (FLN) DADA, Mohamed Drissi (M.) Secrétaire Général, Conseil de la Nation Secrétaire général -

Chapter 3: an Overview of Swedish Constitutional History

Perfecting Parliament Succession, and the Riksdag Acts). It is this portion--the written constitution--that defines the electoral system, specifies the organization of parliament, the relation of the king to parliament, and characterizes many of the constraints that define the limits of governmental activities. These written rules directly shape the broad outlines of Swedish governance, and most clearly characterize the general manner in which the preferences of Swedish citizens are used to determine which specific public policies are put in place. It bears noting, this usage of the term constitution differs somewhat from that used by some Swedish scholars. The term constitution, as used here, refers to the fundamental procedures and constraints faced by Swedish government, rather then the subset of relevant legal documents which claim constitutional status, per se. By the usage adopted here, the Swedish state may be said to have operated under four different constitutions: one written in 1809, one that emerged from amendment in 1866, one that emerged from amendment and additional structural and electoral reform in 1920, and one that was adopted by major structural reforms in 1970. That is to say, the result of major reforms of fundamental procedures and constraints is regarded as creating a new constitution. (There were only two Instruments of Government during the period of interest, those of 1809 and 1975, but there have been four substantially different procedures for making new laws.) This convention is faithful to the discussion above, and simplifies the description of major reforms. The result of the major reforms of the Riksdag adopted in 1866 and in 1909-20 period will be referred to as the Constitution of 1866 and Constitution of 1920, rather than some less descriptive and more cumbersome phrase. -

Fully Acceptable Policies on Homosexuality in The

“Fully Acceptable” Policies on Homosexuality in the Swedish Parliament between 1933-2010 Master’s Thesis The Department of Government Uppsala December 2020 Author: Markus Sjölén Gustafsson Supervisor: Per Adman Abstract This study looks at the development in policy towards homosexuals in Sweden from criminalization to constitutional protection. A study on the ideational development in parliament has yet to be conducted. By studying the frames expressed in the official documents between 1933 and 2010 the study analyses ideas in terms of problems and solutions to describe how change occurred. The result is that Swedish policy towards homosexuals has been determined by two frames of understanding: a sexual frame and an emotional frame. The policy process of the frames developed similarly in terms of institutionalization. Initially both frames saw homosexuals as dangerous which resulted in a different legal status. The frames gradually harmonized with a new scientific understanding that reinterpreted homosexuality as harmless and the different legal status problematic. Keywords: LGBT-rights, Swedish Parliament, frame analysis, path-dependency, critical junctures, policy, harmonization Word count: 19987 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ..................................................................................................................................................... 2 1. Introduction ....................................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Previous -

Meeting of the OECD Global Parliamentary Network 1-2 October 2020 List of Participants

as of 02/10/2020 Meeting of the OECD Global Parliamentary Network 1-2 October 2020 List of participants MP or Chamber or Political Party Country Parliamentary First Name Last Name Organisation Job Title Biography (MPs only) Official represented Pr. Ammar Moussi was elected as Member of the Algerian Parliament (APN) for the period 2002-2007. Again, in the year Algerian Parliament and Member of Peace Society 2017 he was elected for the second term and he's now a member of the Finance and Budget commission of the National Algeria Moussi Ammar Parliamentary Assembly Member of Parliament Parliament Movement. MSP Assembly. In addition, he's member of the parliamentary assembly of the Mediterranean PAM and member of the executif of the Mediterranean bureau of tha Arab Renewable Energy Commission AREC. Abdelmajid Dennouni is a Member of Parliament of the National People’s Assembly and a Member of finances and Budget Assemblée populaire Committee, and Vice president of parliamentary assembly of the Mediterranean. He was previously a teacher at Oran Member of nationale and Algeria Abdelmajid Dennouni Member of Parliament University, General Manager of a company and Member of the Council of Competitiveness, as well as Head of the Parliament Parliamentary Assembly organisaon of constucng, public works and hydraulics. of the Mediterranean Member of Assemblée Populaire Algeria Amel Deroua Member of Parliament WPL Ambassador for Algeria Parliament Nationale Assemblée Populaire Algeria Parliamentary official Safia Bousnane Administrator nationale Lucila Crexell is a National Senator of Argentina and was elected by the people of the province of Neuquén in 2013 and reelected in 2019. -

UNDP RS NARS and Indepen

The National Assembly of the Republic of Serbia Serbia AND INDEPENDENT BODIES SERBIA THE REPUBLIC OF OF ASSEMBLY NATIONAL NATIONAL ASSEMBLY OF THE REPUBLIC OF SERBIA AND INDEPENDENT BODIES 253 NATIONAL ASSEMBLY OF THE REPUBLIC OF SERBIA AND INDEPENDENT BODIES NATIONAL ASSEMBLY OF THE REPUBLIC OF SERBIA AND INDEPENDENT BODIES Materials from the Conference ”National Assembly of the Republic of Serbia and Independent Bodies” Belgrade, 26-27 November 2009 and an Overview of the Examples of International Practice Olivera PURIĆ UNDP Deputy Resident Representative a.i. Edited by Boris ČAMERNIK, Jelena MANIĆ and Biljana LEDENIČAN The following have participated: Velibor POPOVIĆ, Maja ŠTERNIĆ, Jelena MACURA MARINKOVIĆ Translated by: Novica PETROVIĆ Isidora VLASAK English text revised by: Charles ROBERTSON Design and layout Branislav STANKOVIĆ Copy editing Jasmina SELMANOVIĆ Printing Stylos, Novi Sad Number of copies 150 in English language and 350 in Serbian language For the publisher United Nations Development Programme, Country Office Serbia Internacionalnih brigada 69, 11000 Beograd, +381 11 2040400, www.undp.org.rs ISBN – 978-86-7728-125-0 The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the United Nations and the United Nations Development Programme. Acknowledgement We would like to thank all those whose hard work has made this publication possible. We are particularly grateful for the guidance and support of the National Assembly of the Republic of Serbia, above all from the Cabinet of the Speaker and the Secretariat. A special debt of gratitude is owed to the representatives of the independent regulatory bodies; the Commissioner for Information of Public Importance and Personal Data Protection, the State Audit Institution, the Ombudsman of the Republic of Serbia and the Anti-corruption Agency. -

Lessons Learned for the Verkhovna Rada by Julia Keutgen Senior Parliamentary Adviser TABLE of CONTENTS

EUROPEAN UNION NATIONAL PARLIAMENTS IMPLEMENTATION OF THE SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS 1 EUROPEAN UNION NATIONAL PARLIAMENTS IMPLEMENTATION OF THE SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS: Lessons learned for the Verkhovna Rada by Julia Keutgen Senior Parliamentary Adviser TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION 3 2. The oversight process: support the government to implement II. GENERAL CONTEXT 4 international commitments 20 Approval of national strategies 20 1. Agenda 2030 and the Sustainable Plenary debates about the SDGs 21 Development Goals 4 Committee oversight 22 EU and the SDGs 4 Post Legislative Scrutiny 23 2. The role of parliament in 3. The oversight of the budget 24 mainstreaming the SDGs 6 Budget formulation 25 Annual budget approval 25 III. INSTITUTIONAL COMMITMENT Overseeing SDG budget and TO THE SDGS 8 expenditures 26 Participatory budgeting 27 1. Awareness raising 8 4. Representation 28 2. Adoption of political declarations and resolutions 10 V. CASE STUDIES 29 3. Adopting a cross-sectoral approach to the SDGs 10 GERMANY 29 ROMANIA 31 4. Institutional approach 11 5. Parliamentary participation in SDG VI. LESSONS LEARNED AND national coordination mechanisms 15 RECOMMENDATIONS FOR THE VRU 33 6. Reporting of the SDGs 15 VII. BIBLIOGRAPHY 38 IV. MAINSTREAMING THE SDGs INTO PARLIAMENTARY PROCESSES 17 VIII. ANNEXES 42 1. The legislative process 17 Annex 1: Institutional commitment to the SDGs for EU national parliaments 43 Identifying legislative priorities related to SDGs and submit draft bills 17 Annex 2: SDGs in the work of national EU parliaments 44 Aligning legislation related to SDGs to national development strategies 18 Annex 3: Reporting on the SDGs by national EU parliaments 47 Checking all legislation against SDGs 19 Participatory legislation 19 EUROPEAN UNION NATIONAL PARLIAMENTS IMPLEMENTATION OF THE SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS 3 INTRODUCTION Since the legislative elections, the implementation of Agenda 2030 has gained political attention in Ukraine. -

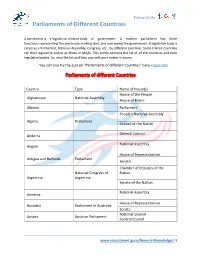

Parliaments of Different Countries

Follow Us On Parliaments of Different Countries A parliament is a legislative, elected body of government. A modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government. A legislative body is called as a Parliament, National Assembly, Congress, etc., by different countries. Some Islamic countries call their legislative bodies as Shora or Majlis. This article contains the list of all the countries and their legislative bodies. So, read the list and help yourself score better in exams. You can also try the quiz on “Parliaments of different Countries” here – Quiz Link Parliaments of different Countries Country Type Name of house(s) House of the People Afghanistan National Assembly House of Elders Albania Parliament People's National Assembly Algeria Parliament Council of the Nation General Council Andorra National Assembly Angola House of Representatives Antigua and Barbuda Parliament Senate Chamber of Deputies of the National Congress of Nation Argentina Argentina Senate of the Nation National Assembly Armenia House of Representatives Australia Parliament of Australia Senate National Council Austria Austrian Parliament Federal Council www.recruitment.guru/General-Knowledge/|1 Follow Us On Parliaments of Different Countries Azerbaijan National Assembly House of Assembly Bahamas, The Parliament Senate Council of Representatives Bahrain National Assembly Consultative Council National Parliament Bangladesh House of Assembly Barbados Parliament Senate House of Representatives National Assembly -

Parliament and Democracy

ang_couv.qxd:Mise en page 1 29.1.2008 10:56 Page 1 PARLIAMENT AND DEMOCRACY IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY a guide to good practice PARLIAMENT AND DEMOCRACY IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY ISBN 978-92-9142-366-8 90000 9 789291 423668 ISBN 978-92-9142-366-8 2006 INTER-PARLIAMENTARY UNION 2006 •Anglais.qxd:Mise en page 1 3.12.2007 10:44 Page i Un Parlement qui rend des comptes I i PARLIAMENT AND DEMOCRACY IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY A GUIDE TO GOOD PRACTICE •Anglais.qxd:Mise en page 1 3.12.2007 10:44 Page ii ii I PARLEMENTS ET DÉMOCRATIE AU 21ÈME SIÈCLE •Anglais.qxd:Mise en page 1 3.12.2007 10:44 Page iii Un Parlement qui rend des comptes I iii PARLIAMENT AND DEMOCRACY IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY A GUIDE TO GOOD PRACTICE Written and edited by David Beetham Inter-Parliamentary Union 2006 •Anglais.qxd:Mise en page 1 3.12.2007 10:44 Page iv iv I PARLIAMENT AND DEMOCRACY IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY Copyright © Inter-Parliamentary Union 2006 All rights reserved Printed in Switzerland First reprint October 2007 ISBN: 978-92-9142-366-8 No part of this publication may be produced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means – electronic, mechanical, via photo- copying, recording, or otherwise – without the prior permission of the Inter- Parliamentary Union. This publication is circulated subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise be lent, sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than in which it is published and without a similar condition, including this condition being imposed on the subsequent publisher.