Parts of Asia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ANATOMY of PRESS CENSORSHIP in INDONESIA the Case of Jakarta, Jakarta and the Dili Massacre

April 27, 1992 Vol. 4, No. 12 ANATOMY OF PRESS CENSORSHIP IN INDONESIA The Case of Jakarta, Jakarta and the Dili Massacre Jakarta, Jakarta, better known as JJ, is a weekly magazine which its editors like to think of as Indonesia's answer to Paris-Match and its reporters treat as something more akin to New York's Village Voice. A brash, colorful, trendy magazine, JJ has been consistently on the limits of what Indonesian authorities regard as acceptable journalism. It was completely in character, therefore, that after the massacre in Dili on November 12, JJ sent two reporters off to East Timor to see what they could find out, and the two came back with some of the most graphic eyewitness accounts available. The results appeared in the issue No. 288, January 4-10, 1992. By the end of January, three editors had been sacked, a result of veiled warnings from the military and what appears to have been an effort by the publisher to pre-empt more drastic action. Asia Watch has obtained documents which offer a fascinating insight into how the case developed and how press censorship works in Indonesia. 1. The Original Story Issue No.288 contained a three-part report on Dili, consisting of an interview with the new regional commander, H.S. Mantiri whose appointment to succeed the Bali-based Major General Sintong Panjaitan had just been announced; an interview with East Timor Governor Mario Carrascalao on some of the reasons East Timorese resented the Indonesian presence; and a series of excerpts from interviews with eyewitnesses to the killings and subsequent arrests. -

The End of Suharto

Tapol bulletin no,147, July 1998 This is the Published version of the following publication UNSPECIFIED (1998) Tapol bulletin no,147, July 1998. Tapol bulletin (147). pp. 1-28. ISSN 1356-1154 The publisher’s official version can be found at Note that access to this version may require subscription. Downloaded from VU Research Repository https://vuir.vu.edu.au/25993/ ISSN 1356-1154 The Indonesia Human Rights Campaign TAPOL Bulletin No. 147 July 1998 The end of Suharto 21 May 1998 will go down in world history as the day when the bloody and despotic rule ofSuharto came to an end. His 32-year rule made him Asia's longest ruler after World War IL He broke many other world records, as a mass killer and human rights violator. In 196511966 he was responsible for the slaughtt:r of at least half a million people and the incarceration of more than 1.2 million. He is also respon{iible for the deaths of 200,000 East Timorese, a third of the population, one of the worst . acts ofgenocide this century. Ignoring the blood-letting that accompanied his seizure of In the last two years, other forms of social unrest took power, the western powers fell over themselves to wel hold: assaults on local police, fury against the privileges come Suharto. He had crushed the world's largest commu nist party outside the Soviet bloc and grabbed power from From the editors: We apologise for the late arrival of President Sukarno who was seen by many in the West as a this issue. -

U Nuni C a Ti

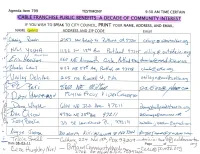

Agenda ltem 799 TEST|MONY 9:30 AM T|ME CERTATN CABLE FRANCHISE PUBLIC BENEFITS: A DECADE OF COIvIIUUT¡ry IuruRTsT lF YOU WISH TO SPEAK TO CITY COUNCIL, PRINT yOUR NAME, ADDRESS, AND EMA¡L. NAME ADDRESS AND ZIP CODE Email C¿ol. ?rr.x ¿-1ç-l ¡^, (^faù (.r Cyã.t c ø c.,\bq\wtka.u'q, \J b\\L\ \ o (ftA l\z t 5\^r \3+d å^ P*[ {^^! 11zo -t û nu4r)h in e?a ^i\ì f - Õ /r,-- l/),;^'r:i: tt6t( ÅE Å;^rr".J( Cr.lo P,,ff^l rro dnorrl ron@-t"eú, kl 2. or.u, L¿-;ç r+.r& C[r*í.t 1rZ+ l,/E çTl ) ?"*+{a/, ofL 17219 CA,/^eed<*.ok5 U^i l"{ Ü¿jr^ tl'¿ ?aÇ y\ø ?-*dt d, p& f,r-.7*r, {eø t{tr ø;/1,/ r-?<-ã*us,Q- lrb cd' I 'Í) tH h+"rs-nt ¡ ftl(ú- ft.vç l/ t D€zGrr*rtr, (rloq t t ( /Þ,1 D *^ Ull.,.lu-- rJÉ 3z"N Nno- 9 7¿ åo^^^L.rl l*¡0,*!+\,o* L, a rot f +f :òwö*oN, -r- ¿./ { 4-t1t xt€, Z*q/ror* 172 // 2Sl on <.q q,@â,-r^' c^rgz .^û FJ yt ltLlßøe\,n h , 3b aü t err s(h^.rst R , \?Z t '| 4r,rd*t^- c+ c.^>t t*l ,. /oo ,¡orrq {,7t r'ì4f ,.- t,trftf ç Pil lTzt¿ þZSxrfa.-*<PS, â.cp' tô :- fffdaG¡'daSnoQ! S^.e-Q-t ---;J8'¿.a, zz+z7 rvwfvu/ l LBn,Et( Pox'rl\-= rC\q, çn.{l€ p¡\ c*[J"no...{=,GT " ,/ i "!ao1 -.{i.ù,page of "*tJ or7 -Date0S-03-ll ?a@gfayy"2ftyy,V*tux u Q;îE^rlrtey N u, ¡ - or;yrÏ.oi,ao n') miÌ ltrl ."-f.l * i' \ *.:1 * " , \'¡e 'Zl.tl " ryi'+wÅlt Ð J,L çfJ 1'¿. -

Massacre Timorese

Timor link, no. 22, February 1992 This is the Published version of the following publication UNSPECIFIED (1992) Timor link, no. 22, February 1992. Timor link (22). pp. 1-8. The publisher’s official version can be found at Note that access to this version may require subscription. Downloaded from VU Research Repository https://vuir.vu.edu.au/25957/ Number 22 February 1992 Massacre highlights Timorese plight East Timor became world news in November when Indonesian troops fired on a funeral procession at the Santa Cruz cemetery, Dill, the territory's capital, killing up to 200 people. The incident tragically highlighted an injustice long ignored by much of the international community. The massacre followed a period of mounting tension in the former Portuguese colony, illegally occupied by Indonesia since 1975, with reports pointing to an escalating campaign of York radio station WBAI were in East Timor 'I turned around - tremendous amount Indonesian repression in the run-up to to report on alleged human rights abuses, of gun fire -- and there were dozens of a planned delegation of Portuguese and were badly beaten by troops while the people lying in the streets. ' parliamentarians in November. The shooting was going on. Bob Muntz, South East Asia project officer delegation was called off on 24 October According to Nairn: 'It was ... a planned with Australia's Community Aid Abroad, after Portuguese concern at Indonesia's and systematic massacre .... This was not a was also present and managed to escape. attempts to control and manipulate the situation where you had some hothead who On return to Melbourne he told a press visit. -

Globalisation, Governance and State-Sponsored Terror: the Case of Indonesia

Julian McKinlay King University of Wollongong Globalisation, governance and State-sponsored terror: The case of Indonesia Rethinking Peace, Conflict and Governance Conference, University of New England, 12-14 February 2020 I pay tribute to the late Professor Peter King (CPACS) and late Dr John Otto Ondawame, former OPM freedom fighter, academic (CPACS), and OPM International Spokesperson who spent much of their lives fighting for West Papuan freedom Indonesia: 7,000 km island chain occupying former Dutch East Indies Territories, and the (former) territories of Netherlands New Guinea incorporating over 3,000 language groups PART ONE THE BIRTH OF STATE FASCISM WITH THE ARRIVAL OF JAPAN 1941: The Japanese line of advance in Dutch East Indies, Portuguese Timor, and Netherlands New Guinea 1941: The Japanese arrival in Dutch East Indies was welcomed by Sukarno (Tropenmuseum) Sukarno worked as principal ‘Collaborator’ for the Japanese during WWII extorting resources / labour from the island archipelago 1953: Sukarno visiting Emperor Hirohito 1944: The Japanese Imperial Army trained a Javanese paramilitary force in with the ideology of Fascism in preparation for the Allied invasion A total of 1.5 million auxiliary paramilitary (C.L.M. Penders, 2002) Japanese Imperial Army members defect, create, & lead the ‘Black Fan’ terrorist group (Times Herald, 15 September 1945) Japanese recounts role fighting to free Indonesi a SIDOMULYO VILLAGE, Indonesia — Rahmat Shigeru Ono enjoyed his dinner of fried noodles, mixed sauteed vegetables and a spicy boiled egg. For most of his life he has eaten Indonesian dishes and he’s used to it, except that it must be accompanied by an “umeboshi” (pickled plum). -

Trump's Indonesian Allies in Bed with ISIS-Backed FPI Militia Seek to Oust

Volume 15 | Issue 9 | Number 6 | Article ID 5034 | Apr 27, 2017 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus Trump’s Indonesian Allies in Bed With ISIS-Backed FPI Militia Seek to Oust Elected President Jokowi Allan Nairn With an introduction by Peter Dale Scott Introduction (preman) of the Islamic Defenders Front or FPI (Front Pembela Islam) that led to Ahok’s The following important essay, by thedefeat. respected and reliable journalist Allan Nairn, reports what Indonesian generals and others The FPI was founded in 1998 with military and have told him of an army-backed movement to police backing, and at first served as the army’s overthrow Indonesia’s civilian-led moderate proxy to beat up left-wing protesters at a time constitutional government. Its thesis isof transition in Indonesian politics.3 1998 was a alarming: that “Associates of Donald Trump in key year: with the retirement of Suharto, the Indonesia have joined army officers and a end of over three decades of “New Order” army vigilante street movement linked to ISIS in a dictatorship, and reforms (reformasi) that led campaign that ultimately aims to oust the to the army’s surrender of its domestic security country’s president… Joko Widodo (known function to a newly created civilian police more commonly as Jokowi).” force. More recently a New York Times editorial, To others, the army’s connection to the FPI is pointing to the electoral defeat on April 19 of less clear now than it was in 1998. At that time Jakarta’s incumbent Christian governor, Basuki the connection was reminiscent of the army’s Tjahaja Purnama (or Ahok), has also expressed use, in its 1965 suppression of the Communist concern about the fate of Indonesia’s fragile PKI, of paramilitary preman or thugs from its democracy.1 But the threat perceived by the creation, the Pemuda Pancasila (Pancasila Times is that from “hard line Islamic groups” Youth). -

The Humanitarian Crisis in East Timor

THE HUMANITARIAN CRISIS IN EAST TIMOR HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON INTERNATIONAL OPERATIONS AND HUMAN RIGHTS OF THE COMMITTEE ON INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED SIXTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION Thursday, September 30, 1999 Serial No. 106±84 Printed for the use of the Committee on International Relations ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 63±316 CC WASHINGTON : 2000 VerDate 11-SEP-98 12:06 Jun 15, 2000 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 63316.TXT HINTREL1 PsN: HINTREL1 COMMITTEE ON INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS BENJAMIN A. GILMAN, New York, Chairman WILLIAM F. GOODLING, Pennsylvania SAM GEJDENSON, Connecticut JAMES A. LEACH, Iowa TOM LANTOS, California HENRY J. HYDE, Illinois HOWARD L. BERMAN, California DOUG BEREUTER, Nebraska GARY L. ACKERMAN, New York CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey ENI F.H. FALEOMAVAEGA, American DAN BURTON, Indiana Samoa ELTON GALLEGLY, California MATTHEW G. MARTINEZ, California ILEANA ROS-LEHTINEN, Florida DONALD M. PAYNE, New Jersey CASS BALLENGER, North Carolina ROBERT MENENDEZ, New Jersey DANA ROHRABACHER, California SHERROD BROWN, Ohio DONALD A. MANZULLO, Illinois CYNTHIA A. MCKINNEY, Georgia EDWARD R. ROYCE, California ALCEE L. HASTINGS, Florida PETER T. KING, New York PAT DANNER, Missouri STEVE CHABOT, Ohio EARL F. HILLIARD, Alabama MARSHALL ``MARK'' SANFORD, South BRAD SHERMAN, California Carolina ROBERT WEXLER, Florida MATT SALMON, Arizona STEVEN R. ROTHMAN, New Jersey AMO HOUGHTON, New York JIM DAVIS, Florida TOM CAMPBELL, California EARL POMEROY, North Dakota JOHN M. MCHUGH, New York WILLIAM D. DELAHUNT, Massachusetts KEVIN BRADY, Texas GREGORY W. MEEKS, New York RICHARD BURR, North Carolina BARBARA LEE, California PAUL E. GILLMOR, Ohio JOSEPH CROWLEY, New York GEORGE P. -

Articles on East Timor Massacre from Peacenet and Associated Networks

ARTICLES ON EAST TIMOR MASSACRE FROM PEACENET AND ASSOCIATED NETWORKS Volume 3: November 20-25, 1991 For more information or additional copies (please enclose US$5. per volume to cover costs): Charles Scheiner, Box 1182, White Plains, NY 10602 USA Tel.914-428-7299 Fax.914-428-7383 email IGC:CSCHEINER or [email protected] Reprinting and distribution without permission is welcomed. Table of Contents EXTRACTS FROM THE DIARY OF KAMAL BAMADHAJ ..................................................................................................................... 3 Dili, East Timor, 29 October 1991................................................................................................................................................................ 3 Maubisse, 2 November 1991 ........................................................................................................................................................................ 3 Dili, 3 November 1991.................................................................................................................................................................................. 4 AUSTRALIAN RELIGIOUS LEADERS SPEAK OUT FOR EAST TIMOR ................................................................................................ 5 SENATOR PELL CONDEMNS MASSACRE.................................................................................................................................................................. 5 "WE CAN'T DENY THE FOREIGN PRESS REPORTS," SAYS GOV. CARRASCALAO -

East Timor-Blaming the Victims-Fact Finding Mission Report-1992-Eng

The 12 November 1991 Massacre in Dili, East Timor, and the Response of the Indonesian Government L.lf)KA£Y International Commission of Jurists(ICJ) Geneva, Switzerland February 1992 INTERNATIONAL COMMISSION OF JURISTS PO Box 145, 1224 Chene-Bougeries, Switzerland tel +4122-49-35-45 fax +4122-49-31-45 If P'£- LiFe -1 c A m Blaming The Victims: The 12 November 1991 Massacre in Dili, East Timor and the Response of the Indonesian Government Introduction From 50 to 200 people were killed and many others wounded on the morning of 12 November 1991 when Indonesian Security forces fired automatic weapons for several minutes at a crowd of approximately 3000 people gathered at Santa Cruz cemetery in Dili, East Timor. Scores were severely beaten and stabbed during the attack. Those present had participated in a procession to the grave of Sebastio Gomes Rangel, a young Timorese man killed on 28 October 1991 when security forces attacked the Motael parish church where he and a number of Timorese had taken refuge. This report summarizes the testimony of eyewitnesses to the 12 November 1991 Santa Cruz massacre in East Timor, including witnesses living outside Indonesia interviewed by the ICJ, and film footage of the incident. (Despite two requests to the Indonesian authorities, the ICJ was not granted permission to enter East Timor in order to carry out an on-site visit or interview witnesses.) The report also reviews official accounts of the incident provided by the Indonesian authorities. It then analyzes the findings and methodology of the National Commission of Inquiry established by the Indonesian Government, which issued its Advance Report on 26 December 1991. -

Oligarchic Cartelization in Post-Suharto Indonesia

Walden University ScholarWorks Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection 2020 Oligarchic Cartelization in Post-Suharto Indonesia Bonifasius -. Hargens Walden University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations Part of the Public Administration Commons, and the Public Policy Commons This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection at ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Walden University College of Social and Behavioral Sciences This is to certify that the doctoral dissertation by Bonifasius Hargens has been found to be complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the review committee have been made. Review Committee Dr. Benedict DeDominicis, Committee Chairperson, Public Policy and Administration Faculty Dr. Marcia Kessack, Committee Member, Public Policy and Administration Faculty Dr. Tamara Mouras, University Reviewer, Public Policy and Administration Faculty Chief Academic Officer and Provost Sue Subocz, Ph.D. Walden University 2019 Abstract Oligarchic Cartelization in Post-Suharto Indonesia: Exploring the Legislative Process of 2017 Election Act by Bonifasius Hargens MPP, Walden University, 2016 BS, University of Indonesia, 2005 Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Public Policy and Administration Walden University [November 2019] Abstract A few ruling individuals from party organizations overpowered Indonesia‘s post-authoritarian, representative democracy. The legislative process of the 2017 Election Act was the case study employed to examine this assumption. -

Justice Ignited: the Dynamics of Backfire Brian Martin (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2007)

Justice ignited: the dynamics of backfire Brian Martin (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2007) This is the text as submitted to the publisher. It differs from the published text due to copyediting changes, different pagination and omission of the index. Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. Sharpeville 7 3. Dili 16 4. Dharasana 24 5. The beating of Rodney King 30 6. Target: whistleblowers 46 7. The dismissal of Ted Steele 55 8. Environmental disasters 69 by Hannah Lendon and Brian Martin 9. The invasion of Iraq 79 10. Abu Ghraib 90 by Truda Gray and Brian Martin 11. Countershock: challenging pushbutton torture 99 by Brian Martin and Steve Wright 12. Terrorism as predictable backfire 109 13. Theory and backfire 118 14. Conclusion 144 Appendix: Methods of inhibiting and amplifying outrage from injustice 154 Acknowledgements Working on the backfire model and this book has been an exciting process because so many people have been involved in exchanging ideas. First of all I thank my collaborators on studies of backfire: Sharon Callaghan, Susan Engel, Truda Gray, David Hess, Sue Curry Jansen, Hannah Lendon, Iain Murray, Samantha Reis, Will Rifkin, Greg Scott, Kylie Smith, and Steve Wright. In my class “Media, war, and peace,” many students used the backfire model on original cases; their investigations helped confirm the value of the model. At seminars and workshops, I’ve received many valuable comments on backfire, including how to extend and refine the model. In preparing this book, David Hess and Steve Wright offered many insightful comments on structure and content. Truda Gray and Greg Scott went through drafts with fine toothcombs, picking up all sorts of points and pushing my understanding. -

Santa Cruz Massacre, 1991

6. Santa Cruz Massacre, 1991 The Santa Cruz massacre was a turning point in the Timorese struggle. In October 1991, a Portuguese parliamentary delegation, working with the resistance and accompanied by media observers, was due in Dili to see the situation on the ground as part of the tripartite process towards a permanent settlement between Indonesia, Portugal and the United Nations. The Indonesian military set themselves the objective of deterring the kind of demonstrations that had occurred with the Pope’s visit in 1989 in front of international media. A campaign of intimidation and harassment was directed at pro-independence groups. Independence advocates who the military suspected might talk to the delegation were rounded up. Meetings were held all over Timor warning people that if they spoke to the delegation, they would be killed. Bishop Belo told Allan Nairn (1992) of The New Yorker that the army was saying that anyone who spoke up or demonstrated in front of the delegation would be hunted down and killed ‘to the seventh generation’. On 27 October 1991, the visit was cancelled over a dispute between Indonesia and Portugal as to whether Australian Jill Jolliffe and Portuguese Rui Araujo and Mario Robalo could be among the journalists approved to travel with the parliamentarians. The next day a pro-independence youth, Sebastião Gomes, was hunted by a government agent and killed with a shot in the stomach while he was seeking sanctuary with other young people in the Motael Church in Dili. During the encounter, an Indonesian intelligence agent also suffered fatal injuries inflicted with a sharp instrument.