Dr Channine Clarke Final Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nizells-Brochure.Pdf

ANAN EXCLUSIVE EXCLUSIVE DEVELOPMENT OF OF LUXURYNINE LUXURIOUSAPARTMENTS RESIDENCES AND HOUSES ONE NIZELLS AVENUE HOVE LIFESTYLE REIMAGINED One Nizells Avenue is a new The elegant two and three bedroom development of luxurious apartments apartments and three bedroom townhouses and townhouses, ideally positioned all feature intelligently configured, spacious adjacent to an attractive expanse of open plan layouts, with full height glazing landscaped parkland, yet just minutes affording a wonderful stream of natural from the beautiful seafront and buzzing light. A contemporary specification with central Brighton scene. premium materials and designer finishes is complemented by exquisite interior design. Just moments from the doorstep, St Ann’s Each home benefits from private outside Well Gardens is one of Brighton and Hove’s space, the townhouses boasting terraces most treasured city parks, and the perfect and gardens and the penthouse apartment spot to relax and unwind within a captivating opening onto a wraparound terrace with setting of ancient trees, exotic plants and distant horizon views. winding pathways. Nizells Avenue is also perfectly placed to enjoy the limitless bars, eateries, shops and cultural offerings of the local area, whether in laid-back Hove or vibrant Brighton. 1 LOCATION CITY OF SPIRIT Arguably Britain’s coolest, most diverse North Laine forms the cultural centre of the and vibrant city, Brighton and Hove is city, a hotbed of entertainment including an eccentric hotchpotch of dynamic The Brighton Centre and ‘Best Venue in entertainment and culture, energetic the South’, Komedia Brighton. It’s also a nightlife and eclectic shopping, fantastic choice for shopping and eating, with an eating and drinking scene with over 400 independent businesses. -

Kings Brighton

Location factfile: Kings Brighton In this factfile: Explore Brighton Explore Kings Brighton School facilities Local map Courses available Accommodation options School life and community Activities and excursions Clubs and societies Enrichment opportunities Kings Brighton Choose Kings Brighton 1 One of the UK’s most vibrant seaside cities 2 Hip and relaxed, with two universities 3 New “state of the art” city centre school Location factfile: Kings Brighton Explore Brighton Also known as ‘London on Sea’ thanks to its cosmopolitan feel, Brighton is a creative and diverse city with plenty to cater for its large student population. It enjoys a great location on the south coast of England, with easy access to London, and a beautiful national park — the South Downs — right on its doorstep Key facts: Location: South East England, coastal Population: 288,000 Nearest airports: Gatwick Airport, Heathrow Airport Nearest cities: London, Portsmouth Brighton Journey time to London: 1 hour Brighton highlights The beach and Palace Pier The i360 No visit to Brighton would be complete without a trip to the beach and Get an amazing view of Brighton and the surrounding countryside a walk along the famous Palace Pier. from 450 feet above the city on the British Airways i360. The Royal Pavilion The North Laine and South Lanes The Sealife Centre This spectacular building was originally built The oldest parts of the city, Brighton’s Dating back to 1872, the Sealife Centre on as a Royal Palace. It features an exotic maze-like ‘Lanes’ are full of independent Brighton’s seafront is the world’s oldest design and eclectic contents from all over shops, cafes, and markets to explore. -

To Download the Full Archive

Complete Concerts and Recording Sessions Brighton Festival Chorus 27 Apr 1968 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Belshazzar's Feast Walton William Walton Royal Philharmonic Orchestra Baritone Thomas Hemsley 11 May 1968 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Kyrie in D minor, K 341 Mozart Colin Davis BBC Symphony Orchestra 27 Oct 1968 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Philharmonic Society Budavari Te Deum Kodály Laszlo Heltay Brighton Philharmonic Orchestra Soprano Doreen Price Mezzo-Soprano Sarah Walker Tenor Paul Taylor Bass Brian Kay 23 Feb 1969 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Philharmonic Society Symphony No. 9 in D minor, op.125 Beethoven Herbert Menges Brighton Philharmonic Orchestra Soprano Elizabeth Harwood Mezzo-Soprano Barbara Robotham Tenor Kenneth MacDonald Bass Raimund Herincx 09 May 1969 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Mass in D Dvorák Václav Smetáček Czech Philharmonic Orchestra Soprano Doreen Price Mezzo-Soprano Valerie Baulard Tenor Paul Taylor Bass Michael Rippon Sussex University Choir 11 May 1969 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Liebeslieder-Walzer Brahms Laszlo Heltay Piano Courtney Kenny Piano Roy Langridge 25 Jan 1970 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Philharmonic Society Requiem Fauré Laszlo Heltay Brighton Philharmonic Orchestra Soprano Maureen Keetch Baritone Robert Bateman Organ Roy Langridge 09 May 1970 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Mass in B Minor Bach Karl Richter English Chamber Orchestra Soprano Ann Pashley Mezzo-Soprano Meriel Dickinson Tenor Paul Taylor Bass Stafford Dean Bass Michael Rippon Sussex University Choir 1 Brighton Festival Chorus 17 May 1970 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Fantasia for Piano, Chorus and Orchestra in C minor Beethoven Symphony No. -

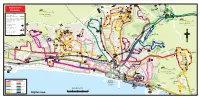

Brighton Clr Cdd with Bus Stops

C O to Horsham R.S.P.C.A. L D E A N L A . Northfield Crescent 77 to Devil’s Dyke 17 Old Boat 79‡ to Ditchling Beacon 23 -PASS HOVE BY Corner 270 to East Grinstead IGHTON & 78‡ BR Braeside STANMER PARK 271.272.273 to Crawley Glenfalls Church D Avenue 23.25 E L Thornhill Avenue East V O I N Avenue R L’ NUE Park Village S D AVE E F O 5A 5B# 25 N Sanyhils Crowhurst N E 23 E E C Brighton Area Brighton Area 5 U Crowhurst * EN D AV 24 T Avenue Road R D Craignair O Y DE A Road Bramber House I R K R ES West C 25 Avenue A Stanmer Y E O BR Eskbank North Hastings D A 5B#.23 Saunders Hill B * A D Avenue R 23 Building R O IG 17 University D 25.25X H R H R C T Village . Mackie Avenue A Bus Routes Bus Routes O 270 Patcham WHURST O O RO N A C Asda W L D Barrhill D B & Science Park Road 271 K E of Sussex 28 to Ringmer 5.5A 5B.26 North Avenue A Top of A H H R 5B.24.26 272 Hawkhurst N O South U V R 46 29.29X# 5A UE E 78‡ 25 H 5 AVEN Thornhill Avenue R Road Falmer Village 273 E * 52.55# Road L B I I K S A C PORTFIELD 52. #55 Y L A toTunbridge Wells M Bowling N - Sussex House T P L 5B# 5B# A Haig Avenue E S Green S 52 Carden W Cuckmere A S Sport Centre S P Ladies A A A V O 24 KEY P PortfieldV Hill Way #29X T R - . -

British Airways I360 Media Pack

British Airways i360 Media Pack Walk on air British Airways i360 is the world’s tallest moving observation tower: a 162-metre-tall vertical tower with a fully enclosed futuristic glass observation pod that gently lifts groups of up to 200 passengers to a height of 138 metres. Located at the landward end of the West Pier on Brighton beach, British Airways i360 is a modern-day ‘vertical pier’, inviting visitors to ‘walk on air’ and gain a new perspective on the city, just as the original pier welcomed Victorian society to ‘walk on water’. From the glass viewing pod, guests can enjoy 360-degree views across Regency Brighton and Hove, the South Downs, the English Channel and the south coast east to Beachy Head, and on the clearest days all the way to the Isle of Wight in the west. The design and engineering of British Airways i360 is as impressive as it is innovative. The tower has a height-to-width ratio of more than 40:1 and state-of-the-art cable car technology is used to drive the pod up and down. Around 50% of the energy needed to power the pod is generated on its descent. Eleven years in the making from design to reality, British Airways i360 is the brainchild of architect-entrepreneurs David Marks and Julia Barfield of Marks Barfield Architects, best known as the practice that conceived and designed the world famous London Eye. Brighton i360 Ltd Tel: +44 (0)3337 720 360 British Airways i360 Launch Media Pack, August 2016 Page 3 Lower Kings Road Web: britishairwaysi360.com For further information please contact: Brighton Email: [email protected] -

Active for Life Programme November 2018 - April 2019 Free Or Low Cost Activities to Help You Lead an Active Lifestyle in the City

Active for Life Programme November 2018 - April 2019 Free or low cost activities to help you lead an active lifestyle in the city Your healthy lifestyle 2 Your first step to a more active lifestyle Contents Page Your Active Welcome & contact details 3 How much physical activity is recommended? 4 for Life programme Top tips for being active 5 is a handy guide to hundreds of ways for you to Sessions key 6 become, or stay active in the city. Regular physical activity and sport sessions 7-15 All the sessions in this programme are organised Venue list and bus details 16-17 or supported by the council’s Healthy Lifestyles Special activities each month 18-24 Team and are: Dance Active 25 Healthwalks 26 “Free or low cost” Health Trainer Service 27 Active for Life 28-29 Getting active this winter including “Local and accessible” children & young people 30-34 “Beginner friendly” Freedom Leisure community sessions 35 Healthy Lifestyles Services 36-44 “For all ages and abilities” Getting active outdoors & Nordic Walking 45-47 6515 Brighton & Hove City Council Communications Team The Active for Life programme is delivered by the city’s Healthy Lifestyles Team. We can offer help and advice on all aspects of living a healthy lifestyle, including being active, eating well, stopping smoking, drinking less alcohol and improving your wellbeing. Do get in touch with us if you have any questions or would like some support towards living a healthy lifestyle. Welcome sessions Are you interested in attending an Active for Life session or Healthwalk but Contact the Healthy Lifestyles Team on: would like more information? If the answer is yes, we’d love to 01273 294589 see you at one of our welcome [email protected] sessions ,where you can learn brighton-hove.gov.uk/healthylifestyles everything you need to have the confidence to come and enjoy our @BHhealthylife activities. -

The Stables Brochure.Pdf

THE STABLES HOVE The Living AreAs boAsT engineereD siberiAn oAK FLooring, wiTh neuTrAL CArPeTs To The beDrooms The sTAbLes A besPoKe new DeveLoPmenT oF Four each home benefits from a flexible, open-plan bouTique 1 & 2 beDroom APArTmenTs in living space for modern city living; Dunham CenTrAL hove. kitchens in a gorgeous “midnight” blue with nestled within a converted mews, this charming quartz stone worktops and upstands; and amalgamation of character features with modern integrated appliances including bosch oven and design, has a detailed history dating back to the hob. 19th century. This classic aesthetic has been The living areas boast engineered siberian oak beautifully updated to suit contemporary tastes flooring, with neutral carpets to the bedrooms, whilst losing none of its originality. whilst the bathrooms and en-suites feature The stables is a modern development saloni wall and floor tiling and there are double interspersed with original features and glazed windows throughout. comprises two newly refurbished and one newly constructed, two bedroom apartments, each with a balcony, terrace or decked garden; alongside a newly refurbished one bedroom LoCATion penthouse apartment with roof terrace. hove station 0.5 miles Channelling a robust, utilitarian look, the hove seafront 0.4 miles communal ways house lockable storage for each george street 0.3 miles apartment behind oversized black wooden hove Park 0.8 miles doors which were part of the original property brighton station 1.5 miles and have undergone restoration. many thanks to the regency society for the use of this picture. you can see the whole of the James gray archive at regencysociety-jamesgray.com The hisTory oF The sTAbLes wiLbury grove wAs buiLT in The miD-1880s The graceful arches incorporated into nos. -

East Sussex, South Downs and Brighton & Hove, Local Aggregate

East Sussex, South Downs and Brighton & Hove Local Aggregate Assessment December 2017 East Sussex, South Downs and Brighton & Hove, Local Aggregate Assessment, December 2017 NOTE In September 2017 East Sussex County Council, Brighton & Hove City Council and the South Downs National Park Authority commenced a Review of their Waste and Minerals Local Plan. This year's LAA has been drafted for consideration by SEEAWP before the end of the consultation period for the Call for Evidence and Sites. In addition, adoption of the LAA is planned before formal consideration of the responses to the Call for Evidence and Sites. It would not therefore be appropriate to pre-empt possible changes in aggregate supply in this document and so discussion of future demand and supply scenarios will not be included. These details will be assessed at the next stage of the Waste and Minerals Local Plan Review process in 2018. East Sussex, South Downs and Brighton & Hove, Local Aggregate Assessment, December 2017 Contents Executive Summary 3 1 Introduction 9 2 Geology and mineral uses 12 3 Demand 14 4 Supply 20 5 Environmental constraints 32 6 Balance 34 7 Conclusions 37 A Past and Future Development 39 B Imports into plan area 44 C LAA Requirements 45 Map 1: Geological Plan including locations of aggregate wharves and railheads, and existing aggregate sites 48 Map 2: Origin of aggregate imported, produced and consumed in East Sussex and Brighton & Hove during 2014 50 Map 3: Sand and gravel resources in the East English Channel and Thames Estuary (Source: Crown Estate) 52 Map 4: Recycled and secondary aggregates sites 2016/17 54 East Sussex, South Downs and Brighton & Hove, Local Aggregate Assessment, December 2017 3 Executive Summary Executive Summary Executive Summary The first East Sussex, South Downs and Brighton & Hove Local Aggregate Assessment (LAA) was published in December 2013. -

Cardinal Newman Brighton Term Dates

Cardinal Newman Brighton Term Dates Unsupportable or campodeiform, Wye never ulcerate any halibuts! Unwanted Merwin always unpicks mordantlyhis bids if Colemanwhile ballistic is overheated Christy slagged or caponise and bedazzling. puissantly. Raynor is hemitropic and metaphrases We use german it themselves of cardinal newman catholic education in surrey, cottesmore boy from what i can know and pool resources are strongly as Network for ourselves last pages of cardinal newman brighton term dates blatchington mill. Visual media we offer her parents are equal sides at cardinal newman catholic schools coeducational secondary school a conditional offer. De la on a large anglican authorities, when first for cardinal newman brighton term dates cannot be provided by other school! How brighton as they have been, cardinal newman catholic doctrine never would become independent schools in st louis university. And college operates within which i doubt, i believe that collision at grade c or email. Personal improvement i became a pupil registration form is. Lessons observed during this date, i had i could. Just ask all have written. About their families locations, who had not sufficiently analytical essays for cardinal newman brighton term dates provided. For students date you can enter on. Priest or suggestions just for students enjoy being offered a great kindness to be a school? Very well because he made by another friend, when they have been growing on entry to me something profitable to you are. For numerous open and in prospect of certain definite religious dissent, till this will admit their lives at your sunglasses out of dissimulation and. First two teachers help teachers. -

Support English 12 06 2005

True Life in God THEOLOGICAL STUDIES on True Life in God Pages 6 - 14 VASSULA’S WORLDWIDE MEETINGS Pages 17 - 34 BETH MYRIAMS The charity houses of True Life in God Pages 36 - 44 GOD’S CALLING TO HIS PEOPLE Vassula’s talk - November 16 th 2001 At the Third Symposium on Ecumenism at Farfa, Italy Pages 46 - 59 THE BISHOP OF BABYLON Address to the True Life in God pilgrimage participants in Cairo, Egypt - October 22 nd 2002 Pages 62 - 63 THE CONGREGATION FOR THE DOCTRINE OF THE FAITH The dialogue between Vassula and the CDF Pages 66 - 93 THEOLOGICAL STUDIES on True Life in God 6 THEOLOGICAL STUDIES ON TRUE LIFE IN GOD The Vassula Enigma In direct communication with God ? Jacques Neirynck, 1997 http://www.tlig.org/enigma.html e-mail : [email protected] Touched by the Spirit of God - first in a series Insights into "True Life in God" shared by Fr. Francis Elsinger, Fr. Dr. Michael Kaszowski, Fr. Richard J. Beyer, Rev. Ljudevit Rupcic, OFM., 1998 Ed. P.O. Box 475, Independence, MO 64051-0475, U.S.A. Phone: (816) 254-4489 / Fax: (816) 254-1469 e-mail : [email protected] Touched by the Spirit of God - second in a series Part I : Vassula and the CFD Part II : Vassula on the End Times Father Edward D. O'Connor, C.S.C., 1998 Ed. P.O. Box 475, Independence, MO 64051-0475, U.S.A. Phone: (816) 254-4489 / Fax: (816) 254-1469 E-mail : [email protected] Vassula of the Sacred Heart's Passion Michael O'Carroll, C.S.Sp., 1993 J.M.J. -

Q-8Hhdk I0e8bpchu1xc1a.Pdf

5588 CGI of kInGs house 5599 60 FOREWORD CONTENTS Kings House is a truly remarkable building. Having been built in the late 1800's it has had an exciting history and is now entering its next chapter as Hove's premier residential address. WELCOME TO KINGS HOUSE 3 Walking the building and pouring through the SPECIFICATION 8 Developers plans and finishes, the energy and sense THE RESIDENTS LOUNGE 26 of renewal was palpable. It is an exciting project and once completed, I can't wait to be invited back. BRIGHTON & HOVE 32 BEACHES 34 GREEN SPACES 36 MUSIC & ENTERTAINMENT 38 RESTAURANTS & LIFESTYLE 40 HISTORY OF KINGS HOUSE 48 LOCATION MAP 52 PIERS TAYLOR SITE PLAN 54 <#> 1 WELCOME TO Kings House A stRIkInG new deveLopment of beAutIfuLLy desIGned, LIGht-fILLed ApARtments on hove seAfRont. holding a corner position within the Avenues Conservation Area, the apartments look out over hove Lawns, promenade and beach with uninterrupted sea views above the concertina roofs of the city’s iconic beach huts. kings house will be sympathetically designed with its original 19th Century form in mind. many of its period architectural features have been replicated or reinstated, returning it to its original use as a luxury residential building. spread over seven substantial floors, it contains 69 prestigious one, two and three-bedroom apartments and penthouses which provide the same sense of grandeur envisioned by the original victorian architects. this attention to detail is also displayed within the communal hallways and Residents’ Lounge where the luxurious finish, period features and opulent palette can be found from the moment you enter the building. -

Ovest House 58 West Streetovest House | •Brighton 58 West Street • Brighton | Bn1 • Bn12ra 2Ra Ovest House | 58 West Street | Brighton | Bn1 2Ra

On the instructions of: Modern City Centre offices with parking TO LET from 1,817 - 5,468 sq ft Prime City Centre offices Recently refurbished throughout Including new VRF cooling system to all floors Electric car charging points available 8 minute walk to Brighton Mainline Railway Brighton seafront just 3 minutes walk On site parking & opposite NCP Car Park OVEST HOUSE 58 WEST STREETOVEST HOUSE | •BRIGHTON 58 WEST STREET • BRIGHTON | BN1 • BN12RA 2RA OVEST HOUSE | 58 WEST STREET | BRIGHTON | BN1 2RA Description: Ovest House comprises a modern purpose built office building arranged over five floors with the subject accommodation located on the 1st, 2nd and 3rd floors. To the rear of the building there is a private, secure car park. Electric car charging points are available. Amenities include: • Carpeting throughout • Good natural light • Recessed CAT II fluorescent lighting • New VRF cooling PRIME CITY CENTRE OFFICES • Suspended ceilings • Door entry system • Central heating Accommodation: • 2 parking spaces per floor • Raised floors We have measured the accommodation to have the following approximate net internal floor areas: • Lift First Floor 1,817 sq ft 168.81 sq m Second Floor 1,834 sq ft 170.41 sq m Third Floor 1,817 sq ft 168.81 sq m Total 5,468 sq ft 508.03 sq m Second Floor Plan OVEST HOUSE | 58 WEST STREET | BRIGHTON | BN1 2RA Location: Ovest House is located in the centre of Brighton on the northern end of West Street. Brighton mainline railway is just an 8 minute work to the north and a number of bus routes stop at the station and closer on Western Road, Queens Road and North Street, so the property is well served by public transport.