Professor/Practitioner Case Development Program - 2000 Case Studies American Institute of Certified Public Accountants

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Comparison of North Korea with Czech Republic and Czechoslovakia Focused on Economic Reforms in Both Countries

A COMPARISON OF NORTH KOREA WITH CZECH REPUBLIC AND CZECHOSLOVAKIA FOCUSED ON ECONOMIC REFORMS IN BOTH COUNTRIES By Radim Vaculovic THESIS Submitted to KDI School of Public Policy and Management in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF PUBLIC POLICY 2004 A COMPARISON OF NORTH KOREA WITH CZECH REPUBLIC AND CZECHOSLOVAKIA FOCUSED ON ECONOMIC REFORMS IN BOTH COUNTRIES By Radim Vaculovic THESIS Submitted to KDI School of Public Policy and Management in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF PUBLIC POLICY 2004 Professor Jin Park 2 ABSTRACT A COMPARISON OF NORTH KOREA WITH CZECH REPUBLIC AND CZECHOSLOVAKIA FOCUSED ON ECONOMIC REFORMS IN BOTH COUNTRIES By Radim Vaculovic North Korea (Democratic People’s Republic of Korea) and Czech Republic or Czechoslovakia - is it possible to compare these two countries? Is there anything what is common for both countries? Many people will answer to this question probably „NOT“. Czech Republic is the country in the middle of Europe, (the Capital – Prague is very often called „the heart of Europe“), which quite successfully transferred social planned economy to market economy. North Korea is on the other hand a country with very central planned economy in North East Asia, where to talk about market economy is something not really possible. So two countries – no geographical connection, (the geographical distance between the two countries is about 8.000 km), no economic connection, each of the state is really in total different pole. Well if a person is satisfied with this explanation it is true there is probably not so much common and these two countries are not really comparable. -

Exchange Rate Policies in Transforming Economies of Central Europe

Sacred Heart University DigitalCommons@SHU WCBT Faculty Publications Jack Welch College of Business & Technology 1997 Exchange Rate Policies in Transforming Economies of Central Europe Lucjan T. Orlowski Sacred Heart University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/wcob_fac Part of the Eastern European Studies Commons, International Business Commons, International Economics Commons, and the Soviet and Post-Soviet Studies Commons Recommended Citation Orlowski, L. T. (1997). Exchange rate policies in transforming economies of central Europe. In L.T. Orlowski & D. Salvatore (Eds.).Trade and payments in Central and Eastern Europe's transforming economies (pp.123-144). Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Jack Welch College of Business & Technology at DigitalCommons@SHU. It has been accepted for inclusion in WCBT Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@SHU. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. 6 EXCHANGE RATE POLICIES IN TRANSFORMING ECONOMIES OF CENTRAL EUROPE Lucjan T. Orlowski INTRODUCTION Exchange rate policies have always been important for policy makers in Central and Eastern Europe. Even before the initiation of market-orien,ted ,economic reforms in the beginning of the 1990s, the command economy system' was con fronted with more deregulated world markets through the export and import of goods and services. Therefore, policy makers could not ignore equilibrium exchange rates with currencies of the leading world economies, although the official rates were arbitrarily set by the Communist authorities at significantly distorted levels. Comprehensive programs of economic deregulation strengthened the impor tance of exchange rate policies for at least three reasons. -

Case Study of Czech and Slovak Koruna

International Journal of Economic Sciences Vol. VI, No. 2 / 2017 DOI: 10.20472/ES.2017.6.2.002 BRIEF HISTORY OF CURRENCY SEPARATION – CASE STUDY OF CZECH AND SLOVAK KORUNA KLARA CERMAKOVA Abstract: This paper aims at describing the process of currency separation of Czech and Slovak koruna and its economic and political background, highlights some of its unique features which ensured smooth currency separation, avoided speculation and enabled preservation of the policy of a stable exchange rate and increased confidence in the new monetary systems. This currency separation was higly appreciated and its scenario and legislative background were reccommended by the IMF for use in other countries. The paper aims also to draw conclusions on performance of selected macroeconomic variables of the two successor countries with impact on monetary policy and exchange rates of successor currencies. Keywords: currency separation, exchange rate, monetary policy, economic performance, inflation, payment system, central bank JEL Classification: E44, E50, E52 Authors: KLARA CERMAKOVA, University of Economics in Prague, Czech Republic, Email: [email protected] Citation: KLARA CERMAKOVA (2017). Brief History of Currency Separation – Case study of Czech and Slovak Koruna. International Journal of Economic Sciences, Vol. VI(2), pp. 30-44., 10.20472/ES.2017.6.2.002 Copyright © 2017, KLARA CERMAKOVA, [email protected] 30 International Journal of Economic Sciences Vol. VI, No. 2 / 2017 1. Introduction Last decade of 20th century was an important period either from political either from economic aspects. Developed market economies mainly in Western Europe and Northern America were on the margin of recession, and in most centrally planned economies the political regimes were collapsing, starting a period of crucial political changes, which resulted, in some cases, into separation of multinational federations and birth of new states. -

Focus on European Economic Integration Special Issue 2009 from the Koruna to the Euro

From the Koruna to the Euro Elena Kohútiková1 Slovakia is one of the few countries to have successfully introduced two currencies and two monetary policies in its economy in a relatively short period of time. This fact offers us an opportunity to compare (1) the period following the establish- ment of both an independent state and an independent currency with (2) the period when the national currency was changed and Slovakia joined the euro area. 1 The Slovak Koruna The second half of 1992 was extremely dynamic and brought the decision to split Czechoslovakia into two independent states on January 1, 1993. One of the issues discussed at that time was the establishment of a new central bank in Slovakia that would assume all the responsibilities that a central bank must fulfill. However, it was also decided that – in the first few months following the setup of both the new states and the new central banks – the Czech Republic and Slovakia would each conduct their own economic policies while maintaining a common monetary policy. In other words, the decision was made to create a monetary union between the two new states and to use the Czechoslovak koruna as the common currency. Initially, the monetary union was meant to exist for at least six months to allow both countries to prepare the launch of their own currencies and monetary policies. For the monetary union to work, the bank boards of both central banks transferred the responsibilities associated with monetary policy management to a Monetary Committee, in which both countries were each represented by three central bank delegates. -

Implementation of the Euro in the Czech Republic

Implementation of the Euro in the Czech Republic Thesis by Nguyen Le Zuzana Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science in Business Administration State University of New York Empire State College 2016 Reader: Tanweer Ali I, Zuzana Nguyen Le, hereby declare that the material contained in this submission is original work performed by me under the guidance and advice of my mentor, Tanweer Ali. Any contribution made to the research by others is explicitly acknowledged in the thesis. I also declare that this work has not previously been submitted in any form for a degree or diploma in any university. Zuzana Nguyen Le, 24.4.2016 Acknowledgement I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my mentor, Mr. Tanweer Ali, for his precise guidance and his patience. I also want to thank all of my close friends who had to listen to my complaints during this stressful period. Especially, I am most grateful for my Thesis-writing-buddy, Dinh Huyen Trang, without whom I would have spent much more time writing the thesis. Our sessions full of food and concentration gave me the needed motivation to finish the work. So thank you. Last but not least, I owe my big thank to my family that supported me and gave me the most possible comfort environment to concentrate. Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 1 History ..................................................................................................................................... -

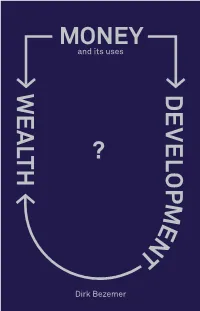

And Its Uses Dirk Bezemer

and its uses Dirk Bezemer Published on the occasion of the farewell reception of Pierre Aeby as Chief Financial Officer (CFO) and member of the Executive Board of Triodos Bank. 2 Money and its uses: development or wealth? Dirk Bezemer Biography Pierre Aeby Dirk Bezemer Pierre Aeby (1956) was CFO and Dirk Bezemer (1971) is Professor in the Executive Board member of Triodos Economics of International Financial Bank NV between 2000 and 2019. Development at the University of His first role, in 1980, was at the Groningen. He developed a research European Credit Bank in Brussels. programme on the consequences of This was followed by fourteen years financial development for financial with the Belgian Generale Bank (now fragility and for equitable and BNP Paribas Fortis). Pierre joined sustainable growth. He published Triodos Bank in 1998 as Managing widely on economic development, Director of Triodos Bank Belgium. on economic methodology, and on During more than two decades with money, credit and financial instability. the bank, as a consistently strong Dirk regularly engages in policy advocate for sustainable economic discussions and contributes to the development, he has helped build its public debate. He is a member of international presence and embed the Sustainable Finance Lab and he the Triodos ethos of consciously writes an economics column for dealing with money. De Groene Amsterdammer. 4 Table of Contents Biography 4 Preface 7 Introduction 11 Features Part 1 1 Money: some history 15 2 Money is a means of settlement 21 3 Money is a social -

Metadata on the Exchange Rate Statistics

Metadata on the Exchange rate statistics Last updated 26 February 2021 Afghanistan Capital Kabul Central bank Da Afghanistan Bank Central bank's website http://www.centralbank.gov.af/ Currency Afghani ISO currency code AFN Subunits 100 puls Currency circulation Afghanistan Legacy currency Afghani Legacy currency's ISO currency AFA code Conversion rate 1,000 afghani (old) = 1 afghani (new); with effect from 7 October 2002 Currency history 7 October 2002: Introduction of the new afghani (AFN); conversion rate: 1,000 afghani (old) = 1 afghani (new) IMF membership Since 14 July 1955 Exchange rate arrangement 22 March 1963 - 1973: Pegged to the US dollar according to the IMF 1973 - 1981: Independently floating classification (as of end-April 1981 - 31 December 2001: Pegged to the US dollar 2019) 1 January 2002 - 29 April 2008: Managed floating with no predetermined path for the exchange rate 30 April 2008 - 5 September 2010: Floating (market-determined with more frequent modes of intervention) 6 September 2010 - 31 March 2011: Stabilised arrangement (exchange rate within a narrow band without any political obligation) 1 April 2011 - 4 April 2017: Floating (market-determined with more frequent modes of intervention) 5 April 2017 - 3 May 2018: Crawl-like arrangement (moving central rate with an annual minimum rate of change) Since 4 May 2018: Other managed arrangement Time series BBEX3.A.AFN.EUR.CA.AA.A04 BBEX3.A.AFN.EUR.CA.AB.A04 BBEX3.A.AFN.EUR.CA.AC.A04 BBEX3.A.AFN.USD.CA.AA.A04 BBEX3.A.AFN.USD.CA.AB.A04 BBEX3.A.AFN.USD.CA.AC.A04 BBEX3.M.AFN.EUR.CA.AA.A01 -

December 12, 1967 Attachment, 'Report on the Czechoslovak Delegation's Negotiations in the United Arab Republic from November 8-19, 1967'

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified December 12, 1967 Attachment, 'Report on the Czechoslovak Delegation's Negotiations in the United Arab Republic from November 8-19, 1967' Citation: “Attachment, 'Report on the Czechoslovak Delegation's Negotiations in the United Arab Republic from November 8-19, 1967',” December 12, 1967, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, National Archives Prague/Novotny Papers/Egypt-box 93/Agreement on purchase of aircrafts. Obtained by Jan Koura and translated for CWIHP by David Růžička. http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/145102 Summary: Summary of successful negotiations between Czechoslovakia and the United Arab Republic for the purchase of L-29 jets. Original Language: Czech Contents: English Translation 3512/ 9 Appendix III. Report on the Czechoslovak delegation's negotiations in the United Arab Republic from November 8-19, 1967 From November 8 until November 19, 1967, the Czechoslovak delegation led by General Director of the Main Technical Administration at the Ministry of Foreign Trade, Ing. František Langer, was in the United Arab Republic where it negotiated about the resolution made by the Central Committee of the Czechoslovak Communist Party from July 4, 1967 (39th meeting point 8) concerning the L-29 jet delivery. Apart from this, issues of mutual payments were addressed in relation to a request for postponing payments related to civil and special agreements – this request was presented at the end of October in this year in Prague at the opportunity of the II. Session of the Joint Czechoslovak Socialist Republic and the United Arab Republic Committee by Mr. Zaki the Egyptian Minister of Economy and Foreign Trade. -

Money Centre No 19 in Memory of Sławomir S

ISSN 2299-632X Money Centre No 19 in memory of Sławomir S. Skrzypek 2019 Q3 teka Banko• • HISTORY ECONOMY EDUCATION Plan of the NBP LEVEL 3 14 12 Stock Exchange Money Centre and Financial Markets 13 Modern Payment 13 Systems 14 Monetary and Economic 12 Unions Creator of Money 15 and Money Production 16 Money in Art 5 3 15 Toilets 4 6 LEVEL 2 C 16 Encounters 1 with Money 9 Stairway to room 7 and 8 Antiquity-Middle Ages 1 10 2 -Modernity 11 3 Monetary Systems 2 4 Bank Street 2 5 Central Bank Numismatist's 3 8 6 Study 7 9 World Wars I and II Polish People's 10 Republic 11 Fall of Communism B 1 LEVEL 1 Laboratory 7 of Authenticity 8 Vault B Toilets ENTRANCE A 0 LEVEL 0 Reception desk Visit our website: www.nbp.pl/centrumpieniadza The NBP Money Centre Magazine Dear readers This issue of “Bankoteka” is released on This issue of “Bankoteka” wouldn’t be complete 1 September – the day on which World War II broke without a photo essay from the Night of Museums, out 80 years ago. The beginning of September which took place on 18 May this year. The front cover also marks the same, round anniversary of of the magazine depicts a group of visitors visiting the evacuation of the gold reserves held by Bank the NBP Money Centre on that evening. In the photo, Polski (the central bank at that time). The first we see a mother, Aleksandra, with her daughter Maja article in the Education section is devoted to the and son Michał, and Feliks, trying to pick up a gold evacuation of the national gold deposits and the bar weighing 400 ounces (12686.35 g) in the “Vault” documents of the Polish central bank. -

The Czech Experience with Capital Flows: Challenges for Monetary Policy

The Czech experience with capital flows: challenges for monetary policy Luděk Niedermayer and Vít Bárta1 1. Introduction Capital flows are a crucial factor in macroeconomic and monetary development. Especially in a small open economy, they usually have a direct and sizeable impact on the exchange rate and, through it, on inflation, competitiveness and economic growth. Should the overall macroeconomic framework become internally inconsistent, capital flows become a typical channel through which the necessary correction materialises. They thus constitute both the channel through which a given macroeconomic setting could be damaged or undermined and a useful adjustment mechanism of re-establishing the economic order. In this paper, we discuss the experience of the Czech economy with capital flows since the beginning of its transformation, which started in 1991. We deal with three different periods characterised by substantial volumes of capital flows with significant implications for the way monetary policy was implemented. Three different developments were occurring within different macroeconomic frameworks, thus having different monetary policy implications. Namely, we deal with: (1) the period 1991–95, when the fixed exchange rate and monetary targeting were maintained; (2) 1996–99, when the Czech National Bank (CNB) widened the fluctuation margin for the koruna and when a speculative attack ultimately led the CNB to abandon the fixed exchange rate regime, with negative implications for exchange rate volatility; and (3) 2002–03, when the CNB, against the background of a steady appreciation trend, faced an appreciation bubble and its subsequent burst. We also briefly discuss a potential future challenge for monetary policy consisting in a high share of repatriated profits in the current account deficit. -

Iso 4217 Pdf 2020

Iso 4217 pdf 2020 Continue The currency code redirects here. This should not be confused with a currency sign. A standard that delineates currency designers and country airline codes showing the price in the ISO 4217 EUR code (bottom left) rather than the CURRENCY mark ISO 4217 is the standard, first published by the International Organization for Standardization in 1978, which delineates currency constructors, country codes (alpha and numerical), and references to small units in three tables: Table A.1 - Current currency and list of fund codes (A.2) - Current fund codes (Current fund codes) of currencies and funds , history and ongoing discussions are supported by SIX interbank clearing on behalf of ISO and the Swiss Standardization Association. The ISO 4217 code list is used in banking and business around the world. In many countries, ISO codes for more common currencies are so well known publicly that exchange rates published in newspapers or placed in banks use only these for currency delineation, not translated currency names or ambiguous currency symbols. ISO 4217 codes are used on airfares and international train tickets to eliminate any ambiguity about the price. The code is forming a list of exchange rates for various base currencies given changed in Thailand, with Thailand Bath as a counter (or quote) currency. Please note that the Korean currency code must be KRW. The first two letters of the code are two letters of ISO 3166-1 alpha-2 (which are also used as the basis for national top-level domains on the Internet), and the third is usually the initial of the currency itself. -

Case Study of the Czech Republic: 1990-1997

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Horvath, Julius; Jonas, Jiri Working Paper Exchange rate regimes in the transition economies: Case study of the Czech Republic: 1990-1997 ZEI Working Paper, No. B 11-1998 Provided in Cooperation with: ZEI - Center for European Integration Studies, University of Bonn Suggested Citation: Horvath, Julius; Jonas, Jiri (1998) : Exchange rate regimes in the transition economies: Case study of the Czech Republic: 1990-1997, ZEI Working Paper, No. B 11-1998, Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn, Zentrum für Europäische Integrationsforschung (ZEI), Bonn This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/39499 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been