This Electronic Thesis Or Dissertation Has Been Downloaded from the King’S Research Portal At

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vividh Bharati Was Started on October 3, 1957 and Since November 1, 1967, Commercials Were Aired on This Channel

22 Mass Communication THE Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, through the mass communication media consisting of radio, television, films, press and print publications, advertising and traditional modes of communication such as dance and drama, plays an effective role in helping people to have access to free flow of information. The Ministry is involved in catering to the entertainment needs of various age groups and focusing attention of the people on issues of national integrity, environmental protection, health care and family welfare, eradication of illiteracy and issues relating to women, children, minority and other disadvantaged sections of the society. The Ministry is divided into four wings i.e., the Information Wing, the Broadcasting Wing, the Films Wing and the Integrated Finance Wing. The Ministry functions through its 21 media units/ attached and subordinate offices, autonomous bodies and PSUs. The Information Wing handles policy matters of the print and press media and publicity requirements of the Government. This Wing also looks after the general administration of the Ministry. The Broadcasting Wing handles matters relating to the electronic media and the regulation of the content of private TV channels as well as the programme matters of All India Radio and Doordarshan and operation of cable television and community radio, etc. Electronic Media Monitoring Centre (EMMC), which is a subordinate office, functions under the administrative control of this Division. The Film Wing handles matters relating to the film sector. It is involved in the production and distribution of documentary films, development and promotional activities relating to the film industry including training, organization of film festivals, import and export regulations, etc. -

The Combined Chiefs of Staff and the Public Health Building, 1942–1946

The Combined Chiefs of Staff and the Public Health Building, 1942–1946 Christopher Holmes The United States Public Health Service Building, Washington, DC, ca. 1930. rom February 1942 until shortly after the end of World War II, the American Fand British Combined Chiefs of Staff operated from a structure at 1951 Constitution Avenue Northwest in Washington, DC, known as the Public Health Building. Several federal entities became embroiled in this effort to secure a suitable meeting location for the Combined Chiefs, including the Federal Reserve, the War Department, the Executive Office of the President, and the Public Health Service. The Federal Reserve, as an independent yet still federal agency, strove to balance its own requirements with those of the greater war effort. The War Department found priority with the president, who directed his staff to accommodate its needs. Meanwhile, the Public Health Service discovered that a solution to one of its problems ended up creating another in the form of a temporary eviction from its headquarters. Thus, how the Combined Chiefs settled into the Public Health Building is a story of wartime expediency and bureaucratic wrangling. Christopher Holmes is a contract historian with the Joint History and Research Office on the Joint Staff at the Pentagon, Arlington, Virginia. 85 86 | Federal History 2021 Federal Reserve Building In May 1940, President Franklin D. Roosevelt began preparing the nation for what most considered America’s inevitable involvement in the war being waged across Europe and Asia. That month, Roosevelt established the National Advisory Commission to the Council of National Defense, commonly referred to as the Defense Commission. -

FEBRUARY/MARCH 2017. Issue 01

FEBRUARY/MARCH 2017. Issue 01. READY FOR WHEREVER YOUR MISSION TAKES YOU ELAMS TOC: The ELAMS TOC Primary mission is to provide effective, reliable space for execution of battlefield C4I. MECC® Shower/Latrine: The AAR MECC® is a fully customizable ISO that allows you to mobilize your mission. SPACEMAX® The SPACEMAX® shelter provides lightweight, durable solutions for rapidly deployable space that reduces costs and risk. 2 armadainternational.com - february/march 2017 MADE IN armadainternational.com - february/march 2017 3 www.AARMobilitySystems.com THE USA FEBRUARY/MARCH 2017 www.armadainternational.com 08 AIR POWER COST VERSUS CREDIBILITY Andrew Drwiega examines maritime patrol aircraft procurement, and the options available for air forces and navies on a budget. 14 20 26 LAND Warfare TURING STIRLING CLASS WAR CATCH-22 VEHICLES FOR CHANGE Stephen W. Miller examines how the designs of Thomas Withington examines the Link-22 tactical Andrew White uncovers some of the latest light armoured vehicles are changing around data link, its workings and what it heralds for advances in vehicle technology to help the world. tomorrow’s naval operations. commandos reach their objectives. 32 38 FUTURE TECHNOLOGIES SEA POWER 44 THE MAN WHO FELL TO EARTH WHAT LIES BENEATH LAND Warfare Parachute technology is over a century old and is Warship definitions are becoming increasingly PREVENTION IS BETTER THAN CURE being continually refined, thanks to advances in blurred due to technological advances. Are we Claire Apthorp explores some of the innovative design and manufacturing, Peter Donaldson moving towards the multipurpose combatant, asks methods being adopted for military vehicle finds out. Dr. -

Mathew Dill Genealogy

Mathew Dill Genealogy Mathew Dill Genealogy A Study of the Dill Family of Dillsburg, York County, Pennsylvania 1698-1934 By I ROSALIE JONES DILL, A.M., LL.M., D.C.L. Member New York and Washington Bar Member of Society of Col cnial Governors and Order of Armorial Beariog-1. Author of "The Amcricao Standard of Liviag" SPOKANE, WASHINGTON 1934 Copyright Sovcmber, 1934 by Rosalie Jone ■ Dill To Amanda Kunkel Dill with affection and esteem _PREFACE In the collection of data concerning the Mathew Dill family of York County, Pennsylvania, and especially of the descendants of the eldest son, grateful thanks is accorded many members of the family. In some instances they have supplied a few names and a short lineage while. in other cases they have given material practically unobtainable elsewhere. For a number of years, the late Rose Lee Dill, devoted her time to the Dill family history especially to the Colonel Matthew line. She was an invalid and her voluminous correspondence, her only link with the outside world, helped to lighten her days of pain. Her material, in manuscript form, has been of great value in connecting various lines with the James Dill chain, the subject matter of Part I. Among those who have been delving into the labyrinth of the Dill connections has been Dr. Alva D. Kenamond whose manuscript has been thankfully used and Mrs. Zula Dill Neely whose interest in the Dill's is unflag ging. Her background and perspective along the trail of the Dill's is unequalled. Several years ago, Reverend Calvin Dill Wilson, Mabel Dill Brown, Kathryn Lee Evans and myself met in conference in Ohio and decided that the scattered information concerning the Dill's might well be as sembled and shaped up in some book form. -

Of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance: an Examination Into Historical Mythmaking

Antony Best The 'ghost' of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance: an examination into historical mythmaking Article (Published version) (Refereed) Original citation: Best, Antony (2006) The 'ghost' of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance: an examination into historical mythmaking. Historical journal, 49 (3). pp. 811-831. ISSN 0018-246X DOI: 10.1017/S0018246X06005528 © 2006 Cambridge University Press This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/26966/ Available in LSE Research Online: August 2012 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. The Historical Journal, 49, 3 (2006), pp. 811–831 f 2006 Cambridge University Press doi:10.1017/S0018246X06005528 Printed in the United Kingdom THE ‘GHOST’ OF THE ANGLO-JAPANESE ALLIANCE: AN EXAMINATION INTO HISTORICAL MYTH-MAKING* ANTONY BEST London School of Economics and Political Science ABSTRACT. Even though the argument runs counter to much of the detailed scholarship on the subject, Britain’s decision in 1921 to terminate its alliance with Japan is sometimes held in general historical surveys to be a major blunder that helped to pave the way to the Pacific War. -

Suez 1956 24 Planning the Intervention 26 During the Intervention 35 After the Intervention 43 Musketeer Learning 55

Learning from the History of British Interventions in the Middle East 55842_Kettle.indd842_Kettle.indd i 006/09/186/09/18 111:371:37 AAMM 55842_Kettle.indd842_Kettle.indd iiii 006/09/186/09/18 111:371:37 AAMM Learning from the History of British Interventions in the Middle East Louise Kettle 55842_Kettle.indd842_Kettle.indd iiiiii 006/09/186/09/18 111:371:37 AAMM Edinburgh University Press is one of the leading university presses in the UK. We publish academic books and journals in our selected subject areas across the humanities and social sciences, combining cutting-edge scholarship with high editorial and production values to produce academic works of lasting importance. For more information visit our website: edinburghuniversitypress.com © Louise Kettle, 2018 Edinburgh University Press Ltd The Tun – Holyrood Road, 12(2f) Jackson’s Entry, Edinburgh EH8 8PJ Typeset in 11/1 3 Adobe Sabon by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd, and printed and bound in Great Britain. A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 1 4744 3795 0 (hardback) ISBN 978 1 4744 3797 4 (webready PDF) ISBN 978 1 4744 3798 1 (epub) The right of Louise Kettle to be identifi ed as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. 2498). 55842_Kettle.indd842_Kettle.indd iivv 006/09/186/09/18 111:371:37 AAMM Contents Acknowledgements vii 1. Learning from History 1 Learning from History in Whitehall 3 Politicians Learning from History 8 Learning from the History of Military Interventions 9 How Do We Learn? 13 What is Learning from History? 15 Who Learns from History? 16 The Learning Process 18 Learning from the History of British Interventions in the Middle East 21 2. -

'Dreadfully Childish, Old Fashioned and Bureaucratic'

The British Army, information management and the First World War revolution in military affairs Hall, BH http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01402390.2018.1504210 Title The British Army, information management and the First World War revolution in military affairs Authors Hall, BH Type Article URL This version is available at: http://usir.salford.ac.uk/id/eprint/47962/ Published Date 2018 USIR is a digital collection of the research output of the University of Salford. Where copyright permits, full text material held in the repository is made freely available online and can be read, downloaded and copied for non-commercial private study or research purposes. Please check the manuscript for any further copyright restrictions. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. The British Army, Information Management and the First World War Revolution in Military Affairs ABSTRACT Information Management (IM) – the systematic ordering, processing and channelling of information within organisations – forms a critical component of modern military command and control systems. As a subject of scholarly enquiry, however, the history of military IM has been relatively poorly served. Employing new and under-utilised archival sources, this article takes the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) of the First World War as its case study and assesses the extent to which its IM system contributed to the emergence of the modern battlefield in 1918. It argues that the demands of fighting a modern war resulted in a general, but not universal, improvement in the BEF’s IM techniques, which in turn laid the groundwork, albeit in embryonic form, for the IM systems of modern armies. -

To Revel in God's Sunshine

To Revel in God’s Sunshine The Story of RSM J C Lord MVO MBE Compiled by Richard Alford and Colleagues of RSM J C Lord © R ALFORD 1981 First Edition Published in 1981 Second Edition Published Electronically in 2013 Cover Pictures Front - Regimental Sergeant Major J C Lord in front of the Grand Entrance to the Old Building, Royal Military Academy Sandhurst. Rear - Army Core Values To Revel in God’s Sunshine The Story of the Army Career of the late Academy Sergeant Major J.C. Lord MVO MBE As related by former Recruits, Cadets, Comrades and Friends Compiled by Richard Alford (2nd Edition - Edited by Maj P.E. Fensome R IRISH and Lt Col (Retd) A.M.F. Jelf) John Lord firmly believed the words of Emerson: “Trust men and they will be true to you. Treat them greatly and they will show themselves great.” Dedicated to SOLDIERS SOLDIERS WHO TRAIN SOLDIERS SOLDIERS WHO LEAD SOLDIERS The circumstances of many contributors to this book will have changed during the course of research and publication, and apologies are extended for any out of date information given in relation to rank and appointment. i John Lord when Regimental Sergeant Major The Parachute Regiment Infantry Training Centre ii CONTENTS 2ND EDITION Introduction General Sir Peter Wall KCB CBE ADC Gen – CGS v Foreword WO1 A.J. Stokes COLDM GDS – AcSM R M A Sandhurst vi Editor’s Note Major P.E Fensome R IRISH vii To Revel in God’s Sunshine Introduction The Royal British Legion Annual Parade at R.M.A Sandhurst viii Chapter 1 The Grenadier Guards, Brighton Police Force 1 Chapter 2 Royal Military College, Sandhurst. -

Contents the Royal Front Cover: Caption Highland Fusiliers to Come

The Journal of Contents The Royal Front Cover: caption Highland Fusiliers to come Battle Honours . 2 The Colonel of the Regiment’s Address . 3 Royal Regiment of Scotland Information Note – Issues 2-4 . 4 Editorial . 5 Calendar of Events . 6 Location of Serving Officers . 7 Location of Serving Volunteer Officers . 8 Letters to the Editor . 8 Book Reviews . 10 Obituaries . .12 Regimental Miscellany . 21 Associations and Clubs . 28 1st Battalion Notes . 31 Colour Section . 33 2006 Edition 52nd Lowland Regiment Notes . 76 Volume 30 The Army School of Bagpipe Music and Highland Drumming . 80 Editor: Army Cadet Force . 83 Major A L Mack Regimental Headquarters . 88 Assistant Editor: Regimental Recruiting Team . 89 Captain K Gurung MBE Location of Warrant Officers and Sergeants . 91 Regimental Headquarters Articles . 92 The Royal Highland Fusiliers 518 Sauchiehall Street Glasgow G2 3LW Telephone: 0141 332 5639/0961 Colonel-in-Chief HRH Prince Andrew, The Duke of York KCVO ADC Fax: 0141 353 1493 Colonel of the Regiment Major General W E B Loudon CBE E-mail: [email protected] Printed in Scotland by: Regular Units IAIN M. CROSBIE PRINTERS RHQ 518 Sauchiehall Street, Glasgow G2 3LW Beechfield Road, Willowyard Depot Infantry Training Centre Catterick Industrial Estate, Beith, Ayrshire 1st Battalion Salamanca Barracks, Cyprus, BFPO 53 KA15 1LN Editorial Matter and Illustrations: Territorial Army Units The 52nd Lowland Regiment, Walcheren Barracks, Crown Copyright 2006 122 Hotspur Street, Glasgow G20 8LQ The opinions expressed in the articles Allied Regiments Prince Alfred’s Guard (CF), PO Box 463, Port Elizabeth, of this Journal are those of the South Africa authors, and do not necessarily reflect the policy and views, official or The Royal Highland Fusiliers of Canada, Cambridge, otherwise, of the Regiment or the Ontario MoD. -

OH-486) 345 Pages OPEN

Processed by: TB HANDY Date: 4/30/93 HANDY, THOMAS T. (OH-486) 345 pages OPEN Assistant Chief of Staff, Operations Division (OPD), U.S. War Department, 1942-44; Deputy Chief of Staff, U.S. Army, 1944-47. DESCRIPTION: Interview #1 (November 6, 1972; pp 1-47) Early military career: Virginia Military Institute; joins field artillery; service in France during World War I; desire of officers to serve overseas during World Wars I and II; reduction to permanent rank after World War I; field artillery school, 1920; ROTC duty at VMI, 1921-25; advanced field artillery course at Fort Sill; Lesley J. McNair; artillery improvements prior to World War II; McNair and the triangular division; importance of army schools in preparation for war; lack of support for army during interwar period; Fox Conner. Command and General Staff School at Leavenworth, 1926-27: intellectual ability of senior officers; problem solving; value of training for development of self-confidence; lack of training on handling personnel problems. Naval War College, 1936: study of naval tactics and strategy by army officers. Comparison of Leavenworth, Army War College and Fort Sill: theory vs. practical training. Joseph Swing: report to George Marshall and Henry Arnold on foul-up in airborne operation in Sicily; impact on Leigh- Mallory’s fear of disaster in airborne phase of Normandy invasion. Interview #2 (May 22, 1973; pp 48-211) War Plans Division, 1936-40: joint Army-Navy planning committee. 2nd Armored Division, 1940-41: George Patton; role of field artillery in an armored division. Return to War Plans Division, 1941; Leonard Gerow; blame for Pearl Harbor surprise; need for directing resources toward one objective; complaint about diverting Normandy invasion resources for attack on North Africa; Operation Torch and Guadalcanal as turning points in war; risks involved in Operation Torch; fear that Germany would conquer Russia; early decision to concentrate attack against Germany rather than Japan; potential landing sites in western Europe. -

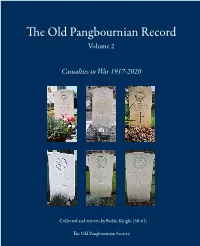

The Old Pangbournian Record Volume 2

The Old Pangbournian Record Volume 2 Casualties in War 1917-2020 Collected and written by Robin Knight (56-61) The Old Pangbournian Society The Old angbournianP Record Volume 2 Casualties in War 1917-2020 Collected and written by Robin Knight (56-61) The Old Pangbournian Society First published in the UK 2020 The Old Pangbournian Society Copyright © 2020 The moral right of the Old Pangbournian Society to be identified as the compiler of this work is asserted in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Design and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, “Beloved by many. stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any Death hides but it does not divide.” * means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior consent of the Old Pangbournian Society in writing. All photographs are from personal collections or publicly-available free sources. Back Cover: © Julie Halford – Keeper of Roll of Honour Fleet Air Arm, RNAS Yeovilton ISBN 978-095-6877-031 Papers used in this book are natural, renewable and recyclable products sourced from well-managed forests. Typeset in Adobe Garamond Pro, designed and produced *from a headstone dedication to R.E.F. Howard (30-33) by NP Design & Print Ltd, Wallingford, U.K. Foreword In a global and total war such as 1939-45, one in Both were extremely impressive leaders, soldiers which our national survival was at stake, sacrifice and human beings. became commonplace, almost routine. Today, notwithstanding Covid-19, the scale of losses For anyone associated with Pangbourne, this endured in the World Wars of the 20th century is continued appetite and affinity for service is no almost incomprehensible. -

Weißbuch 2004

Weißbuch 2004 Weißbuch 2004 Analyse Bilanz Perspektiven Bundesministerium für Landesverteidigung Wien www.bundesheer.at Analyse Bilanz Perspektiven 1 Impressum: Medieninhaber/Herausgeber: Bundesministerium für Landesverteidigung, 1090 Wien Redaktion/Layout: Kontrollsektion/Abteilung Berichte und Weißbuch Layout Titelseite: Gruppe Kommunikation Herstellung: BMLV/Heeresdruckerei, 1030 Wien, Arsenal R 2004 Wien, März 2005 2 Analyse Bilanz Perspektiven Weißbuch 2004 Inhaltsverzeichnis 1. Vorwort des Bundesministers 5.5. Europäische Sicherheitsstrategie (ESS) 52 für Landesverteidigung 5 5.5.1 Vergleich zwischen USA und EU 53 5.6. Militärpolitik und Militärstrategie 2. Präambel 7 53 5.6.1 Militärpolitik 53 3. Lage, Bedrohungen und 5.6.2 Militärstrategie 53 Risiken 9 5.6.3 Rüstungspolitik 54 3.1. Sicherheitspolitische Lage 9 5.7 Wehrsystem Österreichs 54 3.1.1 Sicherheit und Sicherheitspolitik 9 5.7.1 Allgemeines 54 3.1.2 Die sicherheitspolitische Lage aus 5.7.2 Grundsätze des Milizsystems 55 globaler Sicht 9 5.7.3 Allgemeine Wehrpflicht 56 3.1.3 Die sicherheitspolitische Lage Europas 11 5.7.4 Wehrsysteme im internationalen 3.1.4 Hauptakteure aus österreichscher Sicht 13 Vergleich 58 3.2. Konfliktfelder und Bedrohungen 21 3.2.1 Geopolitische Wende 21 5.7.5 Wehrpflicht oder 3.2.2 Sicherheitspolitische Risiken 21 Freiwilligen(Berufs)armee? 58 3.2.3 Bedrohungsformen 21 6. Rechtsgrundlagen 65 4. Das Österreichische 6.1. Grundlegende nationale Rechts- Bundesheer in der Gesellschaft 29 normen 65 4.1. Streitkräfte, Gesellschaft und Staat 6.1.1 Wehrsysteme und Aufgaben 65 im demokratiepolitischen System 29 6.1.2 Wehrgesetz 2001 (WG 2001) 68 4.1.1 Zweck der Militärorganisation und 6.1.3 Mitwirkung im Rahmen der GASP 69 Positionierung der Streitkräfte in 6.1.4 Rechtsnormen für internationale der Gesellschaft 29 Aufgaben 69 4.1.2 Streitkräfte in funktionaler 6.1.5 Militärbefugnisgesetz, Neutralität Transformation 30 Oberbefehl 70 4.1.3 Streitkräfte in gesellschaftlicher 6.2.