Allgemeines Über Die Bibel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

East Syriac Christianity in Mongol-Yuan China (12Th 14Th Centuries)

Orientalia biblica et christiana 18 East Syriac Christianity in Mongol-Yuan China (12th–14th centuries) Bearbeitet von Li Tang 1. Auflage 2011. Buch. XVII, 169 S. Hardcover ISBN 978 3 447 06580 1 Format (B x L): 17 x 24 cm Gewicht: 550 g Weitere Fachgebiete > Religion > Christliche Kirchen & Glaubensgemeinschaften Zu Inhaltsverzeichnis schnell und portofrei erhältlich bei Die Online-Fachbuchhandlung beck-shop.de ist spezialisiert auf Fachbücher, insbesondere Recht, Steuern und Wirtschaft. Im Sortiment finden Sie alle Medien (Bücher, Zeitschriften, CDs, eBooks, etc.) aller Verlage. Ergänzt wird das Programm durch Services wie Neuerscheinungsdienst oder Zusammenstellungen von Büchern zu Sonderpreisen. Der Shop führt mehr als 8 Millionen Produkte. Li Tang East Syriac Christianity in Mongol-Yuan China 2011 Harrassowitz Verlag · Wiesbaden ISSN 09465065 ISBN 978-3-447-06580-1 III Acknowledgement This book is the outcome of my research project funded by the Austrian Science Fund (Fonds zur Förderung der wissenschaftlichen Forschung, abbreviated as FWF) from May 2005 to April 2008. It could not be made possible without the vision of FWF in its support of researches and involvement in the international scientific community. I take this opportunity to give my heartfelt thanks, first and foremost, to Prof. Dr. Peter Hofrichter who has developed a passion for the history of East Syrian Christianity in China and who invited me to come to Austria for this research. He and his wife Hilde, through their great hospitality, made my initial settling-in in Salzburg very pleasant and smooth. My deep gratitude also goes to Prof. Dr. Dietmar W. Winkler who took over the leadership of this project and supervised the on-going process of the research out of his busy schedule and secured all the ways and means that facilitated this research project to achieve its goals. -

Tombstone Carvings from AD 86

Tombstone Carvings from AD 86 Did Christianity Reach China In the First Century? † Wei-Fan Wang Retired Professor Nanjing Theological Seminary 1 This study, carried out as part of the Chaire de recherche sur l’Eurasie (UCLy), will be issued in English in the volume The Acts of Thomas Judas, in context to be published in the Syro- Malabar Heritage and Research Centre collection, Kochin (Indian Federation) 2 Table of contents I. The Gospel carved on stone ......................................................................................... 5 Fig. 1 situation of Xuzhou .............................................................................................. 5 Fig. 2 : The phoenixes and the fish ................................................................................ 6 II. The Creation and the Fall ........................................................................................... 7 Fig. 3: Domestic animals ................................................................................................ 7 Fig. 4: temptation of Eve ................................................................................................ 7 Fig. 5: The cherubim and the sword ............................................................................... 8 ..................................................................................................................................... 9 Fig. 6: The exit of the Eden garden ................................................................................ 9 Fig. 7: Pillar of ferocious -

Jingjiao Under the Lenses of Chinese Political Theology

religions Article Jingjiao under the Lenses of Chinese Political Theology Chin Ken-pa Department of Philosophy, Fu Jen Catholic University, New Taipei City 24205, Taiwan; [email protected] Received: 28 May 2019; Accepted: 16 September 2019; Published: 26 September 2019 Abstract: Conflict between religion and state politics is a persistent phenomenon in human history. Hence it is not surprising that the propagation of Christianity often faces the challenge of “political theology”. When the Church of the East monk Aluoben reached China in 635 during the reign of Emperor Tang Taizong, he received the favorable invitation of the emperor to translate Christian sacred texts for the collections of Tang Imperial Library. This marks the beginning of Jingjiao (oY) mission in China. In historiographical sense, China has always been a political domineering society where the role of religion is subservient and secondary. A school of scholarship in Jingjiao studies holds that the fall of Jingjiao in China is the obvious result of its over-involvement in local politics. The flaw of such an assumption is the overlooking of the fact that in the Tang context, it is impossible for any religious establishments to avoid getting in touch with the Tang government. In the light of this notion, this article attempts to approach this issue from the perspective of “political theology” and argues that instead of over-involvement, it is rather the clashing of “ideologies” between the Jingjiao establishment and the ever-changing Tang court’s policies towards foreigners and religious bodies that caused the downfall of Jingjiao Christianity in China. This article will posit its argument based on the analysis of the Chinese Jingjiao canonical texts, especially the Xian Stele, and takes this as a point of departure to observe the political dynamics between Jingjiao and Tang court. -

The Multiple Identities of the Nestorian Monk Mar Alopen: a Discussion on Diplomacy and Politics

_full_alt_author_running_head (neem stramien B2 voor dit chapter en nul 0 in hierna): 0 _full_alt_articletitle_running_head (oude _articletitle_deel, vul hierna in): Introduction _full_article_language: en indien anders: engelse articletitle: 0 Introduction 37 Chapter 3 The Multiple Identities of the Nestorian Monk Mar Alopen: A Discussion on Diplomacy and Politics Daniel H.N. Yeung According to the Nestorian Stele inscriptions, in the ninth year of the Zhen- guan era of the Tang Dynasty (635 AD), the Nestorian monk Mar Alopen, carry- ing with him 530 sacred texts1 and accompanied by 21 priests from Persia, arrived at Chang’an after years of traveling along the ancient Silk Road.2 The Emperor’s chancellor, Duke3 Fang Xuanling, along with the court guard, wel- comed the guests from Persia on the western outskirts of Chang’an and led them to Emperor Taizong of Tang, whose full name was Li Shimin. Alopen en- joyed the Emperor’s hospitality and was granted access to the imperial palace library4, where he began to undertake the translation of the sacred texts he had 1 According to the record of “Zun jing 尊經 Venerated Scriptures” amended to the Tang Dynasty Nestorian text “In Praise of the Trinity,” there were a total of 530 Nestorian texts. Cf. Wu Changxing 吳昶興, Daqin jingjiao liuxing zhongguo bei: daqin jingjiao wenxian shiyi 大秦景 教流行中國碑 – 大秦景教文獻釋義 [Nestorian Stele: Interpretation of the Nestorian Text ] (Taiwan: Olive Publishing, 2015), 195. 2 The inscription on the Stele reads: “Observing the clear sky, he bore the true sacred books; beholding the direction of the winds, he braved difficulties and dangers.” “Observing the clear sky” and “beholding the direction of the wind” can be understood to mean that Alopen and his followers relied on the stars at night and the winds during the day to navigate. -

Nestorians Jǐngjiàotú 景教徒

◀ Neo-Confucianism Comprehensive index starts in volume 5, page 2667. Nestorians Jǐngjiàotú 景教徒 Nestorians refer to Christians who follow Nestorians first translated their scriptures into Chinese Nestorius, a leader of an early Eastern Chris- and established a Nestorian church in Chang’an. After tian tradition. Persecution for heresy forced the that many Nestorians came to China either by land from Nestorians toward Central and East Asia, includ- Central Asia or by sea from Persia (Iran). The Nestorian Stele was erected in 781, a time of relative prosperity for ing China. As the first generation of Christians Chinese Nestorianism. It is said to have been inscribed coming to China, they arrived in the Tang court by a Nestorian priest named “Adam” (“Jingjing” in Chi- in the early seventh century, and remained in the nese) with the sponsorship of a larger congregation. The country for two hundred years. stele offers a brief but thorough history of Nestorianism in Tang China. According to manuscript sources, the Ne- storian leader Adam translated about thirty-five scriptures hristianity was introduced to China during the into Chinese. Several of these translations survived as the Tang dynasty (618– 907 ce) and became widely manuscripts from Dunhuang; one of them is identified as known as “Jingjiao” (Luminous Teaching) dur- Gloria in excélsis Deo in Syriac texts. However, after 845 ing the Tianqi period (1625– 1627) of the Ming dynasty the Nestorians virtually disappeared in Chinese sources, (1368– 1644) after the discovery of a luminous stele (a having suffered political persecution under the reign of carved or inscribed stone slab or pillar used for commem- the Emperor Wuzong. -

Director's Address

NJG 02 Director’s Address Faith and Order from Today into Tomorrow (Director’s Address) I. China, Contextuality and Visible Unity As the WCC Commission on Faith and Order meets for the first time in mainland China, we remember with gratitude the witness of Alopen and other Assyrian Christians of the 7th century to what was then called in China the “Luminous Religion”, until Assyrian Christianity virtually disappeared under persecution centuries later; we remember the witness of Franciscan friars; the enlightened and inculturated ministry of the Jesuits; and the work of Orthodox missionaries, some of them later recognised as martyrs. We remember the witness of the first Protestant missionaries early in the 19th century and their concern for the translation of Scriptures, without losing sight of the tragic connection between the Protestant presence in China, colonialism, and the tragedy of opium addiction. The secular history of Christianity in China has been a history marked by fascination for this civilisation; by attempts at Western colonisation; by the search for an autonomous Chinese Christianity; and by much suffering. It imposes respect rather than quick judgement. Almost one hundred years ago, in May 1922, the Chinese Protestant churches held in Shanghai a National Christian Conference attended by one thousand people, half of them foreign missionaries, half of them Chinese. The theme of the conference was “The Chinese Church”. A “massive volume” published for the occasion was titled The Christian Occupation of China1. The Conference issued a message called “The United Church”. We Chinese Christians who represent the various leading denominations, the Conference message read, “express our regret that we are divided by the denominationalism which comes from the West”2. -

NEH Summer Seminar: Central Asia in World History Final Project Sam Thomas University School Hunting Valley, OH <[email protected]

NEH Summer Seminar: Central Asia in World History Final project Sam Thomas University School Hunting Valley, OH <[email protected]> In this project, students will be asked to use a variety of primary sources to answer a central historical question: Were the Nestorians truly Christian? The Nestorians were a heretical sect of Christianity that made its way to east Asia in the second half of the first millennium. Much of Nestorian history is obscure, but when European monks arrived in Asia in the thirteenth century they found practitioners who claimed to be Christian, although it is clear that they had incorporated elements of other religions (particularly Buddhism) into their beliefs and practice. In order to complete this exercise, students will wrestle with a number of questions, large and small: • How should they use evidence that is scattered across centuries and thousands of miles? • How reliable is a given source, when it is written by someone from outside the culture he is observing? • How can archeological artifacts be ‘read’? • What does it mean to be a Christian, and by extension, what does it mean to follow any given faith? There are a lot of documents here, and you can pull them some of the texts out as you see fit. If you’d like an electronic copy of this packet, feel free to send me an email. Document A: Berkshire Encyclopedia of China Christianity was introduced to China during the Tang dynasty (618-907) and became widely known as “Jingjiao” (Luminous Teaching) during the Tianqui period (1625-1627) of the Ming dynasty (1368-1644) after the discovery of a luminous stele (a stone pillar used for commemorative purposes). -

Confucian and Christian Canons

論儒家經典西譯與基督教聖經中譯 247 Confucian and Christian Canons 論儒家經典西譯與基督教聖經中譯 Dai Wei-Yang 戴維揚 CONFUCIAN AND CHRISTIAN CANONS 百le initial ideological encounter between Chines€. and Europeans was carriedout mainly by Christian missionaries. Merchants and politicians, with their profit and power orientation, cared little about cultural contacts. Only the educated Christian missionaries bridged the ideological gulf between the Oriental and the Occidental.甘lese missionaries were following out one of the commands of their Lord: Go ye therefore, and teach all na位ons , baptizing 也em in the name of the Father, teaching them to observe all things whatsoever I have commended you. • . 1 Christian teachings had already carried missionaries and proselytes 切 almost every corner of the world. Since the Chinese comprise almost a quarter of the world's popula tion, the territory of China represents one of the most important missionary areas on earth. Missionary efforts in a culturally advanced country such as China, however, are !"~lOre complicated than in countries lacking highly-developed cultural identities. In the history of Christianity's proselytizing activities in China, three groups of Christian missionaries came to the fore at three different times. In chronological order, they are the Nestorians, the Catholics, and the Protestants. The goals of 血 is article will be to examine the accomplishments of each group in regard to making the Bible available to the Chinese on one hand, and Confucian canons to the West, on the other. A. The Nestor i ans The first group of Christian missionaries to reach the Middle Kingdom was the 1. Matthew 28 :19-20. Sc riptural references are usually to the King James Version, unless otherwise noted. -

Catholic Missionaries on China's Qinling Shu Roads

Catholic Missionaries on China’s Qinling Shu Roads: Including an account of the Hanzhong Mission at Guluba David L B Jupp URL: http://qinshuroads.org/ September 2012. Addenda & Corrigenda: November 2013, April 2015, July 2016 & January 2018. Minor edits January 2020. Abstract: The background to this document is found in the history of China’s Shu Roads that passed through the Qinling and Ba Mountains for many years. The roads have linked the northern and southern parts of western China since the earliest records and probably before. In all that time, the common description of the Shu roads was that they were “hard”. In the Yuan, Ming and Qing periods when China was open and accessible, foreign travellers visited the Shu Roads and some left accounts of their travels. Among the early travellers were Catholic Missionaries who moved into the west of China to spread Christianity. This document first outlines the historical environment of the open periods and then identifies various events and Catholic Priests who seem to have travelled the Shu Roads or have left descriptions that are of interest today. The main focus of this document is on the recorded experiences of Missionaries mostly from the Jesuit, Franciscan and Vincentian orders of the Catholic Church of Rome who travelled to the Hanzhong Basin. The main items include: Marco Polo’s (circa 1290) account of travels in China which many Priests who arrived later had read to find out about China; Jesuit Fr. Étienne Faber’s travels to Hanzhong in 1635; Jesuit Fr. Martino Martini’s description of Plank Roads in his Atlas of China in 1655; Franciscan Fr. -

The Centuries-Old Dialogue Between Buddhism and Christianity

Acta Theologica 2009: 2 M. Clasquin-Johnson THE CENTURIES-OLD DIALOGUE BETWEEN BUDDHISM AND CHRISTIANITY ABSTRACT This article examines the pre-history of today’s dialogue between Buddhists and Christians. Contrary to what one might think, pre-modern Europeans did have some understanding of Buddhism, however limited and distorted it might have been. Asians during the same period had a far better chance of understanding Christianity, because of the widespread presence of the Nestorian Church from Arabia to China. We do have evidence that inter- action between Buddhists and Christians lead to some creative synthesis between the two. 1. INTRODUCTION Early in January 2000, Peter Steinfels, a staff reporter at the New York Times, wrote that all too often, the only news about religion is that there is no news. Religious development, he says, occurs at a glacial pace, even when we look at things over the course of an entire millennium. Today’s list of the most im- portant religions looks much the same as that of a thousand years ago. True, some of the contenders have faded from the scene: Odin and Thor have few devotees today. Also, there have been plenty of internal struggles. But no new religions have arisen (Steinfels 2000). One could argue that he is wrong. There is currently a revival of interest in the old Norse gods in the west, under the name Asatru. The Baha’i faith is clearly an interesting and important new candidate in the list of religions. One could also ask whether or not the Mormons, to name just one example, have not moved so far from normative Christianity as to constitute a new religion (not, of course that the Mormons would agree with such an evaluation). -

Catholicism in 21St Century China

Catholicism in 21st Century China Joseph You Guo Jiang, SJ BEATUS POPULUS, CUIUS DOMINUS DEUS EIUS Copyright, 2017, Union of Catholic Asian Editor-in-chief News ANTONIO SPADARO SJ All rights reserved. Except for any fair dealing permitted under the Hong Kong Editorial Board Copyright Ordinance, no part of this Antonio Spadaro SJ – Director publication may be reproduced by any Giancarlo Pani SJ – Vice-Director means without prior permission. Inquires Domenico Ronchitelli SJ –Senior Editor should be made to the publisher. Giovanni Cucci SJ, Diego Fares SJ, Francesco Occhetta SJ, Giovanni Sale SJ Title: La Civiltà Cattolica, English Edition Emeritus editor: Virgilio Fantuzzi SJ, Giandomenico Mucci SJ, GianPaolo Salvini SJ Published by Union of Catholic Asian News P.O. Box 80488, Cheung Sha Wan, Kowloon, Hong Kong Phone: +852 2727 2018 Fax: +852 2772 7656 www.ucanews.com Publishers: Michael Kelly SJ and Robert Barber Production Manager: Rangsan Panpairee CATHOLICISM IN 21st CENTURY CHINA Catholicism in 21st Century China Joseph You Guo Jiang, SJ Christianity first came to China over one thousand years ago but it did not last long. Alopen, a Syrian monk, introduced Nestorian Christianity in the Tang Dynasty and founded several monasteries and churches. Nestorian Christianity reemerged in 1 the Mongol era in the early 14th century. Nestorian Christianity declined in China substantially in the mid-14th century. Roman Catholicism in China grew at the expense of the Nestorians during the late Yuan dynasty. Franciscan Bishop John of Montercorvino began his evangelization mission of the Mongols in Beijing, but his mission ceased with the end of the Mongol Yuan Dynasty in 1368. -

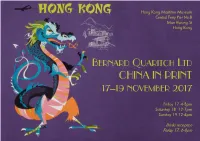

China in Print 2017

Hong Kong Maritime Museum Central Ferry Pier No.8 Man Kwong St Hong Kong Friday 17 4-8pm Saturday 18 12-7pm Sunday 19 12-4pm ARNOLD, J. Souvenir de Macau. Middlesbrough, Hood & Co. Ltd, 1921. For enquiries on any of the items in this catalogue, please contact: Andrea Mazzocchi - [email protected] Oblong 8vo, ll. 25 [title page and 24 halftone BERNARD QUARITCH LTD plates, captioned in Portu- 40 South Audley St, London W1K 2PR guese, image size approxi- Tel.: +44 (0)20 7297 4888 mately 2½ x 3½ inches Fax: +44 (0)20 7297 4866 (6.4 x 8.9 cm)]; a little fox- ing to fore-edge of title E-mail: [email protected] page; bound in original grey wrappers, tied with Mastercard and Visa accepted. green cord, woodcut view If required, postage and insurance will be charged at cost. of harbour with orange highlights on upper wrapper; overall in very good condition. £250 / HK$ 2600 Other titles from our stock can be browsed at www.quaritch.com A scarce souvenir album in an attractively designed wrapper, containing Bankers: 24 tourist views of Macau, all captioned in Portuguese. Bankers: Barclays Bank Plc, Level 27, 1 Churchill Place, London E14 5HP Sort Code: 20-65-90 Account Number: 10511722 Swift: BARC GB22 The atmosphere in Macau, developed by a unique blend of European Sterling Account: IBAN GB62 BARC 206590 10511722 and Far Eastern influences, made the port a desirable destination for the U.S.Dollar Account: IBAN GB10 BARC 206590 63992444 early twentieth-century continental visitor – and those who didn’t have Euro Account: IBAN GB91 BARC 206590 45447011 the opportunity to make the trip could experience this exotic destination Cheques should be made payable to 'Bernard Quaritch Ltd' visually.