Democracy at a Crossroads

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

July 3, 2011 Transcript

© 2011, CBS Broadcasting Inc. All Rights Reserved. PLEASE CREDIT ANY QUOTES OR EXCERPTS FROM THIS CBS TELEVISION PROGRAM TO "CBS NEWS' FACE THE NATION." July 3, 2011 Transcript GUESTS: GOV. DEVAL PATRICK, D-Mass. GOV. JOHN KASICH, R-Ohio GOV. SCOTT WALKER, R-Wis. MAYOR ANTONIO VILLARAIGOSA, D-Los Angeles MODERATOR/ PANELIST: Bob Schieffer, CBS News Political Analyst This is a rush transcript provided for the information and convenience of the press. Accuracy is not guaranteed. In case of doubt, please check with FACE THE NATION - CBS NEWS (202) 457-4481 TRANSCRIPT BOB SCHIEFFER: Today on FACE THE NATION, Washington and how it looks from outside the Beltway. On this July 4th weekend, Washington remains in gridlock. So we’re checking in with four elected officials from around the country--Massachusetts Democratic Governor Deval Patrick, Wisconsin’s Republican Governor Scott Walker, Ohio’s Republican Governor John Kasich, and Los Angeles Democratic Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa. What is the impact with the Washington impasse in their states? What will be the impact out in the country if the President and Congress are unable to reach a deal to raise the debt limit? It’s all next on FACE THE NATION. ANNOUNCER: FACE THE NATION with CBS News chief Washington correspondent Bob Schieffer. And now from Washington, Bob Schieffer. BOB SCHIEFFER: And, good morning again. Welcome to FACE THE NATION on this Fourth of July weekend. Governor Patrick is in Rockport, Massachusetts; Ohio Governor John Kasich is in Richmond, Massachusetts; Wisconsin Republican Scott Walker joins us from his state capital in Madison; and Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa is out at the Aspen Ideas Festival in Aspen, Colorado. -

Electoral Order and Political Participation: Election Scheduling, Calendar Position, and Antebellum Congressional Turnout

Electoral Order and Political Participation: Election Scheduling, Calendar Position, and Antebellum Congressional Turnout Sara M. Butler Department of Political Science UCLA Los Angeles, CA 90095-1472 [email protected] and Scott C. James Associate Professor Department of Political Science UCLA Los Angeles, CA 90095-1472 (310) 825-4442 [email protected] An earlier version of this paper was presented at the Annual Meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association, April 3-6, 2008, Chicago, IL. Thanks to Matt Atkinson, Kathy Bawn, and Shamira Gelbman for helpful comments. ABSTRACT Surge-and-decline theory accounts for an enduring regularity in American politics: the predictable increase in voter turnout that accompanies on-year congressional elections and its equally predictable decrease at midterm. Despite the theory’s wide historical applicability, antebellum American political history offers a strong challenge to its generalizability, with patterns of surge-and-decline nowhere evident in the period’s aggregate electoral data. Why? The answer to this puzzle lies with the institutional design of antebellum elections. Today, presidential and on-year congressional elections are everywhere same-day events. By comparison, antebellum states scheduled their on- year congressional elections in one of three ways: before, after, or on the same day as the presidential election. The structure of antebellum elections offers a unique opportunity— akin to a natural experiment—to illuminate surge-and-decline dynamics in ways not possible by the study of contemporary congressional elections alone. Utilizing quantitative and qualitative materials, our analysis clarifies and partly resolves this lack of fit between theory and historical record. It also adds to our understanding of the effects of political institutions and electoral design on citizen engagement. -

Congressional Record—Senate S1857

March 14, 2019 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE S1857 for all of Stew’s colleagues, that level Happy trails, buddy. not your typical vote on an appropria- of good cheer and concern for others f tions or authorization bill. It doesn’t really has been typical for a dozen concern a nomination or an appoint- RESERVATION OF LEADER TIME years. ment. This will be a vote about the That is why his departure has trig- The PRESIDING OFFICER. Under very nature of our Constitution, the gered an avalanche of tributes from the previous order, leadership time is separation of powers, and how this gov- people all over Washington and beyond, reserved. ernment functions henceforth. people—many of them junior people— f The Framers gave Congress the whom he wrote back with advice, met power of the purse in article I of the for coffee, shared some wisdom; this CONCLUSION OF MORNING Constitution. It is probably our great- sprawling family tree of men and BUSINESS est power. Now the President is claim- women who all feel that, one way or The PRESIDING OFFICER. Morning ing that power for himself under a another, they owe a significant part of business is closed. guise of an emergency declaration to their success and careers to him. On f get around a Congress that repeatedly that note, I have to say I know exactly RELATING TO A NATIONAL EMER- would not authorize his demand for a how they feel. So today I have to say goodbye to an GENCY DECLARED BY THE border wall. all-star staff leader who took his job PRESIDENT ON FEBRUARY 15, The President has not justified the about as seriously as anybody you will 2019 emergency declaration. -

Rejected Write-Ins

Rejected Write-Ins — Official Travis County — November 8, 2016, Joint General and Special Elections — November 08,2016 Page 1 of 28 12/08/2016 02:12 PM Total Number of Voters : 496,044 of 761,470 = 65.14% Precincts Reporting 247 of 268 = 92.16% Contest Title Rejected Write-In Names Number of Votes PRESIDENT <no name> 58 A 2 A BAG OF CRAP 1 A GIANT METEOR 1 AA 1 AARON ABRIEL MORRIS 1 ABBY MANICCIA 1 ABDEF 1 ABE LINCOLN 3 ABRAHAM LINCOLN 3 ABSTAIN 3 ABSTAIN DUE TO BAD CANDIA 1 ADA BROWN 1 ADAM CAROLLA 2 ADAM LEE CATE 1 ADELE WHITE 1 ADOLPH HITLER 2 ADRIAN BELTRE 1 AJANI WHITE 1 AL GORE 1 AL SMITH 1 ALAN 1 ALAN CARSON 1 ALEX OLIVARES 1 ALEX PULIDO 1 ALEXANDER HAMILTON 1 ALEXANDRA BLAKE GILMOUR 1 ALFRED NEWMAN 1 ALICE COOPER 1 ALICE IWINSKI 1 ALIEN 1 AMERICA DESERVES BETTER 1 AMINE 1 AMY IVY 1 ANDREW 1 ANDREW BASAIGO 1 ANDREW BASIAGO 1 ANDREW D BASIAGO 1 ANDREW JACKSON 1 ANDREW MARTIN ERIK BROOKS 1 ANDREW MCMULLIN 1 ANDREW OCONNELL 1 ANDREW W HAMPF 1 Rejected Write-Ins — Official Travis County — November 8, 2016, Joint General and Special Elections — November 08,2016 Page 2 of 28 12/08/2016 02:12 PM Total Number of Voters : 496,044 of 761,470 = 65.14% Precincts Reporting 247 of 268 = 92.16% Contest Title Rejected Write-In Names Number of Votes PRESIDENT Continued.. ANN WU 1 ANNA 1 ANNEMARIE 1 ANONOMOUS 1 ANONYMAS 1 ANONYMOS 1 ANONYMOUS 1 ANTHONY AMATO 1 ANTONIO FIERROS 1 ANYONE ELSE 7 ARI SHAFFIR 1 ARNOLD WEISS 1 ASHLEY MCNEILL 2 ASIKILIZAYE 1 AUSTIN PETERSEN 1 AUSTIN PETERSON 1 AZIZI WESTMILLER 1 B SANDERS 2 BABA BOOEY 1 BARACK OBAMA 5 BARAK -

Inprez: an Epic, Bizarre Primary Coda in the Assassina- Trump Victory Secures GOP Tion of President Nomination; Sanders’ Upset Kennedy

V21, 35 Thursday, May 5, 2016 INPrez: An epic, bizarre primary coda in the assassina- Trump victory secures GOP tion of President nomination; Sanders’ upset Kennedy. It came at a time when of Clinton prolongs the slog Republicans took a second, long look By BRIAN A. HOWEY at Trump, hoping INDIANAPOLIS – When the dust to see a future settled on one of the most bizarre political president. Instead, sequences in modern Indiana history, Hoo- they got a tabloid sier Republican voters had mostly settled the reality star on the Republican presidential race for Donald Trump verge of a land- while prolonging the primary slog for Hillary slide victory who Clinton with Bernie didn’t know when Sanders’ 53-47% vic- to let up. tory. On the The Indiana Democratic side, primary ended on a voters witnessed frenzied week-long a sprawling Bernie pace as four candi- Sanders rally at dates and an ex-pres- Bobby Knight’s endorsement of Donald Trump became a the foot of the ident courted Hoosiers at more than 50 rallies decisive component of the Manhattan billionaire’s landslide Soldiers & Sailors and retail stops. In the final crescendo, this win over Ted Cruz in the Indiana primary that helped clear Monument and epic drama became surreal as Donald Trump the field on Wednesday. (HPI Photo by Mark Curry) below the corpo- used a National Enquirer article to allege that Ted Cruz’s father was involved with Lee Harvey Oswald Continued on page 4 Pence on Cruz control By BRIAN A. HOWEY INDIANAPOLIS – For Gov. Mike Pence, the presi- dential maelstrom that roared through the state has left him, at least temporarily, twisting, twisting, twisting in the political winds. -

Ballot Initiatives and Electoral Timing

Ballot Initiatives and Electoral Timing A. Lee Hannah∗ Pennsylvania State University Department of Political Sciencey Abstract This paper examines the effects of electoral timing on the results of ballot initiative campaigns. Using data from 1965 to 2009, I investigate whether initiative campaign re- sults systematically differ depending on whether the legislation appears during special, midterm, or presidential elections. I also consider the electoral context, particularly the effects of surging presidential candidates on ballot initiative results. The results suggest that initiatives on morality policy are sensitive to the electoral environment, particularly to “favorable surges” provided by popular presidential candidates. Preliminary evidence suggests that tax policy is unaffected by electoral timing. Introduction The increasing use of the ballot initiative has led to heightened interest in both the popular media and among scholars. Some of the most contentious issues in American politics, once reserved for debate among elected representatives, are now being decided directly by the me- dian voter. Yet the location of the median voter fluctuates from election to election based on a number of factors that influence turnout and shape the demographic makeup of voters in a given year. This suggests that votes on ballot initiatives may be influenced by the same factors that are known to influence electoral composition. In this paper, I contrast initiatives appearing on midterm and special election ballots with those held during presidential elections, deriving hypotheses from Campbell’s (1960) theory of electoral surge and decline. I examine whether electoral timing does systematically affect results. ∗Prepared for the 2012 State Politics and Policy Conference, Rice University and University of Houston, February 16-18, 2012. -

American Review of Politics Volume 37, Issue 1 31 January 2020

American Review of Politics Volume 37, Issue 1 31 January 2020 An open a ccess journal published by the University of Oklahoma Department of Political Science in colla bora tion with the University of Okla homa L ibraries Justin J. Wert Editor The University of Oklahoma Department of Political Science & Institute for the American Constitutional Heritage Daniel P. Brown Managing Editor The University of Oklahoma Department of Political Science Richard L. Engstrom Book Reviews Editor Duke University Center for the Study of Race, Ethnicity, and Gender in the Social Sciences American Review of Politics Volume 37 Issue 1 Partisan Ambivalence and Electoral Decision Making Stephen C. Craig Paulina S. Cossette Michael D. Martinez University of Florida Washington College University of Florida [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Abstract American politics today is driven largely by deep divisions between Democrats and Republicans. That said, there are many people who view the opposition in an overwhelmingly negative light – but who simultaneously possess a mix of positive and negative feelings toward their own party. This paper is a response to prior research (most notably, Lavine, Johnson, and Steenbergen 2012) indicating that such ambivalence increases the probability that voters will engage in "deliberative" (or "effortful") rather than "heuristic" thinking when responding to the choices presented to them in political campaigns. Looking first at the 2014 gubernatorial election in Florida, we find no evidence that partisan ambivalence reduces the importance of party identification or increases the impact of other, more "rational" considerations (issue preferences, perceived candidate traits, economic evaluations) on voter choice. -

Partisan Gerrymandering and the Construction of American Democracy

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE Partisan Gerrymandering and the Construction of American Democracy In Partisan Gerrymandering and the Construction of American Democracy, Erik J. Engstrom offers an important, historically grounded perspective on the stakes of congressional redistricting by evaluating the impact of gerrymandering on elections and on party control of the U.S. national government from 1789 through the reapportionment revolution of the 1960s. In this era before the courts supervised redistricting, state parties enjoyed wide discretion with regard to the timing and structure of their districting choices. Although Congress occasionally added language to federal- apportionment acts requiring equally populous districts, there is little evidence this legislation was enforced. Essentially, states could redistrict largely whenever and however they wanted, and so, not surpris- ingly, political considerations dominated the process. Engstrom employs the abundant cross- sectional and temporal varia- tion in redistricting plans and their electoral results from all the states— throughout U.S. history— in order to investigate the causes and con- sequences of partisan redistricting. His analysis -

Presidential Approval Ratings on Midterm Elections OLAYINKA

Presidential Approval Ratings on Midterm Elections OLAYINKA AJIBOLA BALL STATE UNIVERSITY Abstract This paper examines midterm elections in the quest to find the evidence which accounts for the electoral loss of the party controlling the presidency. The first set of theory, the regression to the mean theory, explained that as the stronger the presidential victory or seats gained in previous presidential year, the higher the midterm seat loss. The economy/popularity theories, elucidate midterm loss due to economic condition at the time of midterm. My paper assesses to know what extent approval rating affects the number of seats gain/loss during the election. This research evaluates both theories’ and the aptness to expound midterm seat loss at midterm elections. The findings indicate that both theories deserve some credit, that the economy has some impact as suggested by previous research, and the regression to the mean theories offer somewhat more accurate predictions of seat losses. A combined/integrated model is employed to test the constant, and control variables to explain the aggregate seat loss of midterm elections since 1946. Key Word: Approval Ratings, Congressional elections, Midterm Presidential elections, House of Representatives INTRODUCTION Political parties have always been an integral component of government. In recent years, looking at the Clinton, Bush, Obama and Trump administration, there are no designated explanations that attempt to explain why the President’s party lose seats. To an average person, it could be logical to conclude that the President’s party garner the most votes during midterm elections, but this is not the case. Some factors could affect the outcome of the election which could favor or not favor the political parties The trend in the midterm election over the years have yielded various results, but most often, affecting the president’s party by losing congressional house seats at midterm. -

Lucas County Board of Elections Election Results for Candidates 2010 to Present

Lucas County Board of Elections Election Results For Candidates 2010 to Present GENERAL ELECTION – NOVEMBER 3, 2015 CERTIFIED NOVEMBER 20, 2015 Page 1. Total Voters: 114,294 39.77% Total Registered: 287,382 Total Precincts: 352 (A.V.B. rolled with proper precinct) Toledo Municipal Court Judge (Full term commencing 01/01/2016) Bill Connelly 42,481 Toledo City Mayor Paula Hicks-Hudson 23,087 Michael P. Bell 11,228 17.33% Carty Finkbeiner 10,276 15.86% Sandy Drabik Collins 9,432 14.55% Sandy Spang 7,028 10.85% Mike Ferner 3,208 4.95% Opal Covey 544 0.84% Toledo City Council-at-Large Cecelia M. Adams 35,236 100.00% Toledo City Council-District 1 Tyrone Riley 6,333 72.20% Jennifer L. Scott 2,438 27.80% Toledo City Council-District 2 Matthew A. Cherry 8,350 70.02% Drew D. Blazsik 3,575 29.98% *= most votes Toledo City Council-District 3 Peter Ujvagi 3,258 52.87% Glen Cook 2,904 47.13% Toledo City Council-District 4 Yvonne Harper 4,777 73.58% Peggy Brown-Morehead 1,715 26.42% Toledo City Council-District 5 Tom Waniewski 9,555 100.00% Toledo City Council-District 6 Lindsay M. Webb 7,289 69.80% Bill Delaney 3,154 30.20% Maumee City Mayor Richard H. Carr 3,308 100.00% Maumee City Council-Unexpired Term Timothy L. Pauken 2,581 64.28% Dyana Davis 1,434 35.72% Maumee City Council-Full Term (elect 3) Daniel G. Hazard 2,409 28.06% John P. -

JOHN WEAVER – Chief Strategist Overview

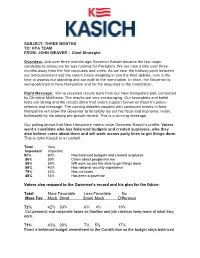

SUBJECT: THREE MONTHS TO: KFA TEAM FROM: JOHN WEAVER – Chief Strategist Overview: Just over three months ago Governor Kasich became the last major candidate to announce he was running for President. We are now a little over three months away from the first caucuses and votes. As we near the halfway point between our announcement and the voters finally weighing in and the third debate, now is the time to assess our standing and our path to the nomination. In short, the Governor is well-positioned in New Hampshire and for the long road to the nomination. Right Message: We’ve received results back from our New Hampshire poll, conducted by Christine Matthews. The results are very encouraging. Our favorables and ballot tests are strong and the results show that voters support Governor Kasich’s policy reforms and message. The coming debates coupled with continued events in New Hampshire will allow the Governor to forcefully lay out his fiscal and economic vision, buttressed by his strong pro-growth record. This is a winning message. Our polling shows that New Hampshire voters value Governor Kasich’s profile. Voters want a candidate who has balanced budgets and created surpluses, who they also believe cares about them and will work across party lines to get things done. This is John Kasich in a nutshell. Total Very Important Important 92% 60% Has balanced budgets and created surpluses 86% 59% Cares about people like me 85% 59% Will work across the aisle to get things done 84% 40% Has national security experience 79% 42% Has cut taxes 48% 14% Has been a governor Voters also respond to the Governor’s record and his plan for the future: Total More Favorable Less Favorable No More Fav Much Smwt Smwt Much Difference 72% 42% 30% 6% 4% 19% Cut personal and corporate taxes so families and job creators keep more of what they earn. -

Clinton Leads in Pennsylvania, Ohio; Ties Bush in Florida, Quinnipiac University Swing State Poll Finds

Peter A. Brown, Assistant Director, (203) 535-6203 Tim Malloy, Assistant Director (203) 645-8043 Rubenstein Associates, Inc., Public Relations Pat Smith (212) 843-8026 FOR RELEASE: FEBRUARY 3, 2015 CLINTON LEADS IN PENNSYLVANIA, OHIO; TIES BUSH IN FLORIDA, QUINNIPIAC UNIVERSITY SWING STATE POLL FINDS --- FLORIDA: Clinton 44 – Bush 43 OHIO: Clinton 47 – Bush 36 PENNSYLVANIA: Clinton 50 – Christie 39 A first look at three critical swing states, Florida, Ohio and Pennsylvania, for the 2016 presidential election is good news for former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, who tops possible Republican contenders in every matchup, except Florida, where she ties former Gov. Jeb Bush, and Ohio, where she ties Gov. John Kasich, according to a Quinnipiac University Swing State Poll released today. Overall, Gov. Bush runs best of any Republican listed against Clinton, the independent Quinnipiac (KWIN-uh-pe-ack) University Poll finds. The Swing State Poll focuses on Florida, Ohio and Pennsylvania because since 1960 no candidate has won the presidential race without taking at least two of these three states. Clinton’s favorability rating tops 50 percent in each state, while Republican ratings range from negative to mixed to slightly positive, except for Bush in Florida and Kasich in Ohio. Of three “Native Son” candidates, measured against Clinton only in their home states, only Ohio Gov. John Kasich gives the Democrat a good run, getting 43 percent to her 44 percent. Matchups between Clinton and her closest Republican opponent in each state show: Florida: Clinton at 44 percent to Bush’s 43 percent; Ohio: Clinton over Bush 47 – 36 percent; Pennsylvania: Clinton tops New Jersey Gov.