Quail Island: Foreshore Resource Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

29 November 2005

University of Auckland Institute of Marine Science Publications List maintained by Richard Taylor. Last updated: 31 July 2019. This map shows the relative frequencies of words in the publication titles listed below (1966-Nov. 2017), with “New Zealand” removed (otherwise it dominates), and variants of stem words and taxonomic synonyms amalgamated (e.g., ecology/ecological, Chrysophrys/Pagrus). It was created using Jonathan Feinberg’s utility at www.wordle.net. In press Markic, A., Gaertner, J.-C., Gaertner-Mazouni, N., Koelmans, A.A. Plastic ingestion by marine fish in the wild. Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology. McArley, T.J., Hickey, A.J.R., Wallace, L., Kunzmann, A., Herbert, N.A. Intertidal triplefin fishes have a lower critical oxygen tension (Pcrit), higher maximal aerobic capacity, and higher tissue glycogen stores than their subtidal counterparts. Journal of Comparative Physiology B: Biochemical, Systemic, and Environmental Physiology. O'Rorke, R., Lavery, S.D., Wang, M., Gallego, R., Waite, A.M., Beckley, L.E., Thompson, P.A., Jeffs, A.G. Phyllosomata associated with large gelatinous zooplankton: hitching rides and stealing bites. ICES Journal of Marine Science. Sayre, R., Noble, S., Hamann, S., Smith, R., Wright, D., Breyer, S., Butler, K., Van Graafeiland, K., Frye, C., Karagulle, D., Hopkins, D., Stephens, D., Kelly, K., Basher, Z., Burton, D., Cress, J., Atkins, K., Van Sistine, D.P., Friesen, B., Allee, R., Allen, T., Aniello, P., Asaad, I., Costello, M.J., Goodin, K., Harris, P., Kavanaugh, M., Lillis, H., Manca, E., Muller-Karger, F., Nyberg, B., Parsons, R., Saarinen, J., Steiner, J., Reed, A. A new 30 meter resolution global shoreline vector and associated global islands database for the development of standardized ecological coastal units. -

Marine Mollusca of Isotope Stages of the Last 2 Million Years in New Zealand

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/232863216 Marine Mollusca of isotope stages of the last 2 million years in New Zealand. Part 4. Gastropoda (Ptenoglossa, Neogastropoda, Heterobranchia) Article in Journal- Royal Society of New Zealand · March 2011 DOI: 10.1080/03036758.2011.548763 CITATIONS READS 19 690 1 author: Alan Beu GNS Science 167 PUBLICATIONS 3,645 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Integrating fossils and genetics of living molluscs View project Barnacle Limestones of the Southern Hemisphere View project All content following this page was uploaded by Alan Beu on 18 December 2015. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. This article was downloaded by: [Beu, A. G.] On: 16 March 2011 Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 935027131] Publisher Taylor & Francis Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37- 41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t918982755 Marine Mollusca of isotope stages of the last 2 million years in New Zealand. Part 4. Gastropoda (Ptenoglossa, Neogastropoda, Heterobranchia) AG Beua a GNS Science, Lower Hutt, New Zealand Online publication date: 16 March 2011 To cite this Article Beu, AG(2011) 'Marine Mollusca of isotope stages of the last 2 million years in New Zealand. Part 4. Gastropoda (Ptenoglossa, Neogastropoda, Heterobranchia)', Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand, 41: 1, 1 — 153 To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/03036758.2011.548763 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03036758.2011.548763 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. -

24 Relationships Within the Ellobiidae

Origin atld evoltctiorzai-y radiatiotz of the Mollrisca (ed. J. Taylor) pp. 285-294, Oxford University Press. O The Malacological Sociery of London 1996 R. Clarke. 24 paleozoic .ine sna~ls. RELATIONSHIPS WITHIN THE ELLOBIIDAE ANTONIO M. DE FRIAS MARTINS Departamento de Biologia, Universidade dos Aqores, P-9502 Porzta Delgada, S6o Miguel, Agores, Portugal ssification , MusCum r Curie. INTRODUCTION complex, and an assessment is made of its relevance in :eny and phylogenetic relationships. 'ulmonata: The Ellobiidae are a group of primitive pulmonate gastropods, Although not treated in this paper, conchological features (apertural dentition, inner whorl resorption and protoconch) . in press. predominantly tropical. Mostly halophilic, they live above the 28s rRNA high-tide mark on mangrove regions, salt-marshes and rolled- and radular morphology were studied also and reference to ~t limpets stone shores. One subfamily, the Carychiinae, is terrestrial, them will be made in the Discussion. inhabiting the forest leaf-litter on mountains throughout ago1 from the world. MATERIAL AND METHODS 'finities of The Ellobiidae were elevated to family rank by Lamarck (1809) under the vernacular name "Les AuriculacCes", The anatomy of 35 species representing 19 genera was ~Ctiquedu properly latinized to Auriculidae by Gray (1840). Odhner studied (Table 24.1). )llusques). (1925), in a revision of the systematics of the family, preferred For the most part the animals were immersed directly in sciences, H. and A. Adarns' name Ellobiidae (in Pfeiffer, 1854). which 70% ethanol. Some were relaxed overnight in isotonic MgCl, ochemical has been in general use since that time. and then preserved in 70% ethanol. A reduced number of Grouping of the increasingly growing number of genera in specimens of most species was fixed in Bouin's, serially Gebriider the family was based mostly on conchological characters. -

Annotated Checklist of New Zealand Decapoda (Arthropoda: Crustacea)

Tuhinga 22: 171–272 Copyright © Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (2011) Annotated checklist of New Zealand Decapoda (Arthropoda: Crustacea) John C. Yaldwyn† and W. Richard Webber* † Research Associate, Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Deceased October 2005 * Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, PO Box 467, Wellington, New Zealand ([email protected]) (Manuscript completed for publication by second author) ABSTRACT: A checklist of the Recent Decapoda (shrimps, prawns, lobsters, crayfish and crabs) of the New Zealand region is given. It includes 488 named species in 90 families, with 153 (31%) of the species considered endemic. References to New Zealand records and other significant references are given for all species previously recorded from New Zealand. The location of New Zealand material is given for a number of species first recorded in the New Zealand Inventory of Biodiversity but with no further data. Information on geographical distribution, habitat range and, in some cases, depth range and colour are given for each species. KEYWORDS: Decapoda, New Zealand, checklist, annotated checklist, shrimp, prawn, lobster, crab. Contents Introduction Methods Checklist of New Zealand Decapoda Suborder DENDROBRANCHIATA Bate, 1888 ..................................... 178 Superfamily PENAEOIDEA Rafinesque, 1815.............................. 178 Family ARISTEIDAE Wood-Mason & Alcock, 1891..................... 178 Family BENTHESICYMIDAE Wood-Mason & Alcock, 1891 .......... 180 Family PENAEIDAE Rafinesque, 1815 .................................. -

Assessment of Ecological Effects on the Receiving Environment from the Discharge of Treated Wastewater from an Army Bay WWTP

Assessment of Ecological Effects on the receiving environment from the discharge of treated wastewater from an Army Bay WWTP (Photo Shane Kelly) Mark James1, Mike Stewart2, Chris Dada2, Shane Kelly3 and Sara Jamieson4 Prepared for Watercare Services Ltd November 2018 1Mark James 2 Streamlined Environmental Ltd Aquatic Environmental Sciences Ltd 3 Coast and Catchment Ltd PO Box 328 4 Tracks Ltd Whangamata 3643 Email: [email protected] Cell: 021 0538379 1 Executive Summary Watercare is preparing an Assessment of Environmental Effects (AEE) for new consents for the continued operation of a wastewater treatment plant and discharge to service growth in the Hibiscus Coast/ Orewa/Whangaparaoa area. The consent application process requires an assessment of the potential effects on the receiving environments and ecological values. The report summarises the status of the existing environment in the Whangaparaoa Passage and wider environment based on existing and new information collected as part of the consent application process. The report then provides an assessment of the potential effects of the existing and then the future discharges on the ecological values if a discharge to the existing discharge point (~1.3 km into the Whangaparaoa Passage in 25 m of water) is the final option. Future scenarios considered for modelling were a small increase in population in the “Short- term” through to ~2031 (to 116,000 PE), an increase in population serviced from a combined WWTP to 160,000 PE in the “Medium-term” (~2041) and up to 192,000 PE in the “Long-term” (~2053). Note that slightly lower populations are now being used for each scenario in the final AEE based on updated growth numbers provided and thus the risk assessment is conservative. -

Fasciolariidae

WMSDB - Worldwide Mollusc Species Data Base Family: FASCIOLARIIDAE Author: Claudio Galli - [email protected] (updated 07/set/2015) Class: GASTROPODA --- Clade: CAENOGASTROPODA-HYPSOGASTROPODA-NEOGASTROPODA-BUCCINOIDEA ------ Family: FASCIOLARIIDAE Gray, 1853 (Sea) - Alphabetic order - when first name is in bold the species has images Taxa=1523, Genus=128, Subgenus=5, Species=558, Subspecies=42, Synonyms=789, Images=454 abbotti , Polygona abbotti (M.A. Snyder, 2003) abnormis , Fusus abnormis E.A. Smith, 1878 - syn of: Coralliophila abnormis (E.A. Smith, 1878) abnormis , Latirus abnormis G.B. III Sowerby, 1894 abyssorum , Fusinus abyssorum P. Fischer, 1883 - syn of: Mohnia abyssorum (P. Fischer, 1884) achatina , Fasciolaria achatina P.F. Röding, 1798 - syn of: Fasciolaria tulipa (C. Linnaeus, 1758) achatinus , Fasciolaria achatinus P.F. Röding, 1798 - syn of: Fasciolaria tulipa (C. Linnaeus, 1758) acherusius , Chryseofusus acherusius R. Hadorn & K. Fraussen, 2003 aciculatus , Fusus aciculatus S. Delle Chiaje in G.S. Poli, 1826 - syn of: Fusinus rostratus (A.G. Olivi, 1792) acleiformis , Dolicholatirus acleiformis G.B. I Sowerby, 1830 - syn of: Dolicholatirus lancea (J.F. Gmelin, 1791) acmensis , Pleuroploca acmensis M. Smith, 1940 - syn of: Triplofusus giganteus (L.C. Kiener, 1840) acrisius , Fusus acrisius G.D. Nardo, 1847 - syn of: Ocinebrina aciculata (J.B.P.A. Lamarck, 1822) aculeiformis , Dolicholatirus aculeiformis G.B. I Sowerby, 1833 - syn of: Dolicholatirus lancea (J.F. Gmelin, 1791) aculeiformis , Fusus aculeiformis J.B.P.A. Lamarck, 1816 - syn of: Perrona aculeiformis (J.B.P.A. Lamarck, 1816) acuminatus, Latirus acuminatus (L.C. Kiener, 1840) acus , Dolicholatirus acus (A. Adams & L.A. Reeve, 1848) acuticostatus, Fusinus hartvigii acuticostatus (G.B. II Sowerby, 1880) acuticostatus, Fusinus acuticostatus G.B. -

Pedipedinae (Gastropoda: Ellobiidae) from Hong Kong

The marine flora and fauna of Hong Kong and southern China III (ed. B. Morton). Proceedings of the Fourth International Marine Biological Workshop: The Marine Flora and Fauna of Hong Kong and Southern China, Hong Kong, 11-29 April 1989. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 1992. PEDIPEDINAE (GASTROPODA: ELLOBIIDAE) FROM HONG KONG Ant6nio M. de Frias Martins Departamento de Biologia, Universidade dos A~ores,P-9502 Ponta Delgada, Siio Miguel, A~ores,Portugal ABSTRACT Two species of Pedipedinae are recorded for the first time from Hong Kong and are here provisionally referred to as Pedipes jouani Montrouzier, 1862 and Microtralia alba (Gassies, 1865), described from New Caledonia. A descriptive study of the reproductive and nervous systems was conducted and confirms previous studies that both genera are consubfamilial. The distribution and dispersal of the species is discussed. INTRODUCTION The Indo-Pacific Ellobiidae are particularly well represented by conspicuous, mangrove- dwelling, macroscopic species, relatively few of which have been studied anatomically. Koslowsky (1933) presented a detailed description of Melampus boholensis 'H. and A. Adams' Pfeiffer, 1856. Morton (1955) described the anatomy of Pythia Roding, 1798, Ellobium Roding, 1798 [E.aurisjudae (L. 1758)l and of the small pedipedinian Marinula King, 1832 [M.filholi Hutton, 18781. Knipper and Meyer (1956) provided good illus- trations of the nervous systems of Ellobium (Auriculodes) gaziensis (Preston, 1913), Cassidula labrella (Deshayes, 1830) and Melampus semisulcatus Mousson, 1869. Cassidula Fhssac, 1821, Ellobium and Pythia were discussed by Beny et al. (1967) and Sumikawa and Miura (1978) studied in detail the reproductive system of Ellobium chinense (Pfeiffer, 1854). -

Kaipara Harbour Targeted Marine Pest Survey May 2019

Kaipara Harbour Targeted Marine Pest Survey May 2019 Melanie Tupe, Chris Woods and Samantha Happy April 2020 Technical Report 2020/008 Kaipara Harbour targeted marine pest survey May 2019 April 2020 Technical Report 2020/008 M. Tupe (nee Vaughan) Environmental Services, Auckland Council C. Woods National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research, NIWA S. Happy Environmental Services, Auckland Council NIWA project: ARC19501 Auckland Council Technical Report 2020/008 ISSN 2230-4525 (Print) ISSN 2230-4533 (Online) ISBN 978-1-99-002214-2 (Print) ISBN 978-1-99-002215-9 (PDF) This report has been peer reviewed by the Peer Review Panel. Review completed on 30 April 2020 Reviewed by two reviewers Name: Samantha Hill Position: Head of Natural Environment Design (Environmental Services) Name: Imogen Bassett Position: Biosecurity Principal Advisor (Environmental Services) Date: 30 April 2020 Recommended citation Tupe, M., C Woods and S Happy (2020). Kaipara Harbour targeted marine pest survey May 2019. Auckland Council technical report, TR2020/008 Cover image: close-up image of the Australian droplet tunicate, Eudistoma elongatum. Photo credit: Chris Woods (NIWA) © 2020 Auckland Council Auckland Council disclaims any liability whatsoever in connection with any action taken in reliance of this document for any error, deficiency, flaw or omission contained in it. This document is licensed for re-use under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence. In summary, you are free to copy, distribute and adapt the material, as long as you attribute it to the Auckland Council and abide by the other licence terms. Executive summary The introduction of new species to an environment in which they did not evolve has been recognised as one of the top threats to ecosystem function and biodiversity. -

Redalyc.Familia Ellobiidae (Gastropoda: Archaeopulmonata

Revista Peruana de Biología ISSN: 1561-0837 [email protected] Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos Perú Paredes, Carlos; Indacochea, Aldo; Cardoso, Franz; Ortega, Kelly Familia Ellobiidae (Gastropoda: Archaeopulmonata) en el litoral peruano Revista Peruana de Biología, vol. 12, núm. 1, 2005, pp. 69-76 Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos Lima, Perú Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=195018466004 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto Rev. peru. biol. 12(1): 69-76 (2005) © Facultad de Ciencias Biológicas UNMSM VersiónFamilia Online Ellobiidae ISSN 1727-9933 en el Perú Familia Ellobiidae (Gastropoda: Archaeopulmonata) en el litoral peruano Family Ellobiidae (Gastropoda: Archaeopulmonata) in the Peruvian coast Carlos Paredes1, Aldo Indacochea2 , Franz Cardoso1 y Kelly Ortega2 Presentado: 12/07/2005 Aceptado: 01/08/2005 Resumen Se reportan 8 especies de Ellobiidae para la Costa Peruana, pertenecientes a las subfamilias Ellobiinae: Ellobium stagnale (Orbigny, 1835) y Sarnia frumentum Petit, 1842; Melampodinae: Melampus carolianus (Lesson, 1842), Melampus olivaceus Carpenter, 1857 y Detracia graminea Morrison, 1846; y Pedipedinae: Marinula acuta (Orbigny, 1835), Marinula concinna (C.B Adams, 1852) y Marinula pepita King, 1831. Seis especies viven asociadas al bosque de manglar en el departamento de Tumbes, y dos en las playas de canto rodado en los límites de la Provincia Peruana. Cuatro especies tropicales se registran por primera vez para el mar peruano: E. -

Intertidal Life of the Tamaki Estuary and Its Entrance, Auckland July 2005 TP373

Intertidal Life of the Tamaki Estuary and its Entrance, Auckland July 2005 TP373 Auckland Regional Council Technical Publication No. 373, 2008 ISSN 1175-205X(Print) ISSN 1178-6493 (Online) ISBN 978-1-877483-47-9 Intertidal life of the Tamaki Estuary and its Entrance, Auckland Bruce W. Hayward1 Margaret S. Morley1,2 1Geomarine Research, 49 Swainston Rd, St Johns, Auckland 2c/o Auckland War Memorial Museum, Private Bag 92 018, Auckland Prepared for Auckland Regional Council Envrionmental Research 2005 The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Auckland Regional Council Approved for ARC publication by: _____________________________ Grant Barnes 21 July 2008 Recommended Citation: Hayward, B. W; Morley, M.S (2005). Intertidal life of the Tamaki Estuary and its entrance, Auckland. Prepared for Auckland Regional Council. Auckland Regional Council Technical Publication Number 373. 72p Contents 1 Executive Summary 1 2 Introduction 3 2.1 Study Area 3 2.2 Rock Types Along the Shore 6 2.3 Origin and Shape of the Tamaki Estuary 6 2.4 Previous Work 7 2.4.1 Ecological Surveys 7 2.4.2 Introduced Species 7 2.4.3 Environmental Pollution 8 2.4.4 Geology 9 2.5 Tamaki Estuary Steering Committee 9 3 Methodology 10 3.1 Survey Methodology 10 3.2 Biodiversity and Specimens 10 4 Intertidal Habitats and Communities 11 4.1 Salt Marsh and Salt Meadow 11 4.2 Mangrove Forest 11 4.3 Seagrass Meadows 12 4.4 Sublittoral Seaweed Fringe 12 4.5 Estuarine Mud 12 4.6 Shelly Sand Flats 12 4.7 Shell Banks and Spits -

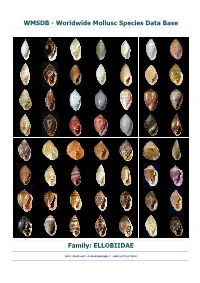

WMSDB - Worldwide Mollusc Species Data Base

WMSDB - Worldwide Mollusc Species Data Base Family: ELLOBIIDAE Author: Claudio Galli - [email protected] (updated 07/set/2015) Class: GASTROPODA --- Clade: HETEROBRANCHIA-PULMONATA-EUPULMONATA-ELLOBIOIDEA ------ Family: ELLOBIIDAE L. Pfeiffer, 1854 (Land) - Alphabetic order - when first name is in bold the species has images Taxa=681, Genus=34, Subgenus=13, Species=287, Subspecies=12, Synonyms=334, Images=187 acteocinoides , Microtralia acteocinoides J.T. Kuroda & T. Habe, 1961 acuminata , Ovatella acuminata P.M.A. Morelet, 1889 - syn of: Myosotella myosotis (J.P.R. Draparnaud, 1801) acuta , Marinula acuta (D'Orbigny, 1835) acuta , Pythia acuta J.B. Hombron & C.H. Jacquinot, 1847 acutispira , Melampus acutispira W.H. Turton, 1932 - syn of: Melampus parvulus L. Pfeiffer, 1856 adamsianus , Melampus adamsianus L. Pfeiffer, 1855 adansonii , Pedipes adansonii H.M.D. de Blainville, 1824 - syn of: Pedipes pedipes (J.G. Bruguière, 1789) adriatica , Ovatella adriatica H.C. Küster, 1844 - syn of: Myosotella myosotis (J.P.R. Draparnaud, 1801) aegiatilis, Pythia pachyodon aegiatilis H.A. Pilsbry & Y. Hirase, 1908 aequalis , Ovatella aequalis (R.T. Lowe, 1832) afer , Pedipes afer J.F. Gmelin, 1791 - syn of: Pedipes pedipes (J.G. Bruguière, 1789) affinis , Marinula affinis A.E.J. Férussac, 1821 - syn of: Pedipes affinis A.E.J. Férussac, 1821 affinis , Laemodonta affinis A.E.J. Férussac, 1821 - syn of: Pedipes affinis A.E.J. Férussac, 1821 affinis , Pedipes affinis A.E.J. Férussac, 1821 alba , Microtralia alba (J. Gassies, 1865) albescens , Ovatella albescens T.V. Wollaston, 1878 - syn of: Ovatella aequalis (R.T. Lowe, 1832) albovaricosa, Pythia albovaricosa L. Pfeiffer, 1853 albus , Melampus albus C.A. Davis, 1904 - syn of: Melampus monile (J.G. -

Invasion Biology of the Asian Shore Crab Hemigrapsus Sanguineus: a Review

Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 441 (2013) 33–49 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jembe Invasion biology of the Asian shore crab Hemigrapsus sanguineus: A review Charles E. Epifanio ⁎ School of Marine Science and Policy, University of Delaware, 700 Pilottown Road, Lewes, DE 19958, USA article info abstract Article history: The Asian shore crab, Hemigrapsus sanguineus, is native to coastal and estuarine habitat along the east coast of Received 19 October 2012 Asia. The species was first observed in North America near Delaware Bay (39°N, 75°W) in 1988, and a variety Received in revised form 8 January 2013 of evidence suggests initial introduction via ballast water early in that decade. The crab spread rapidly after its Accepted 9 January 2013 discovery, and breeding populations currently extend from North Carolina to Maine (35°–45°N). H. sanguineus Available online 9 February 2013 is now the dominant crab in rocky intertidal habitat along much of the northeast coast of the USA and has displaced resident crab species throughout this region. The Asian shore crab also occurs on the Atlantic coast Keywords: fi Asian shore crab of Europe and was rst reported from Le Havre, France (49°N, 0°E) in 1999. Invasive populations now extend Bioinvasion along 1000 km of coastline from the Cotentin Peninsula in France to Lower Saxony in Germany (48°– Europe 53°N). Success of the Asian shore crab in alien habitats has been ascribed to factors such as high fecundity, Hemigrapsus sanguineus superior competition for space and food, release from parasitism, and direct predation on co-occurring crab North America species.