(In)Justice and Protest in Bucharest After the Colectiv Fire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

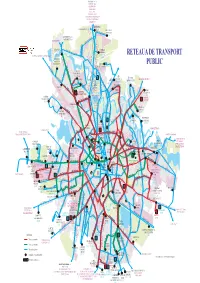

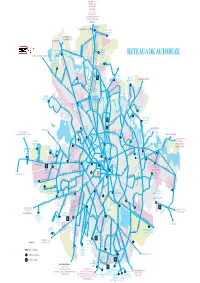

RETEA GENERALA 01.07.2021.Cdr

OTOPENI 780 783 OSTRATU R441 OTOPENI R442 PERIS R443 PISCU R444 GRUIU R446 R447 MICSUNESTII MARI R447B MOARA VLASIEI R448 SITARU 477 GREENFIELD STRAULESTI 204 304 203 204 Aleea PrivighetorilorJOLIE VILLE BANEASA 301 301 301 GREENFIELD 204 BUFTEA R436 PIATA PRESEI 304 131 Str. Jandarmeriei261 304 STRAULESTI Sos. Gh. Ionescu COMPLEX 97 204 205 304 261 Sisesti BANEASA RETEAUA DE TRANSPORT R402 205 131 261 335 BUFTEA GRADISTEA SITARU R402 261 205 R402 R436 Bd. OaspetilorStr. Campinita 361 605 COMPLEX 112 205 261 97 131 261301 COMERCIAL Sos. Bucuresti Ploiesti PUBLIC COLOSSEUM CARTIER 231 Sos. Chitilei Bd. Bucurestii Noi Sos. Straulesti R447 R447B R448 R477 203 335 361 605 780 783 112 R441 R442 R443 R444HENRI R446 COANDA 231 Bd. Aerogarii R402 97 605 231 112 112 CARTIER 112 301 112 DAMAROAIA 131 R436 335 231 Sos. Chitilei R402 24 331R436 CFR Str. Alex. Serbanescu 112 CONSTANTA CARTIER MERII PETCHII R409 112 DRIDU Str. N. Caramfil R402 Bd. Laminorului AUTOBAZA ANDRONACHE 331 65 86 112 135 243 Bd. NORDULUI112 301 382 Bd. Gloriei24 Str. Jiului 605 Sos. 112Pipera 135 Sos. Chitilei Poligrafiei PIATA PLATFORMA Bd. BucurestiiPajurei Noi 231 243 Str. Peris MEZES 780 783 INDUSTRIALA Str. PRESEI Str.Oi 3 45 65 86 331 243 3 45 382 PASAJ Sos. Bucuresti Ploiesti 3 41 243 PIPERA 382 DEPOUL R447 R447BR448 R477 112 231 243 i 65 86 97 243 16 36 COLENTINA 131105 203 205 261203 304 231 261 304 330 135 343 n tuz BUCURESTII NOI a R441 R442 R443 c 21 i CARTIER 605 tr 231R441 361 R442 783 R443 R444 R446 DEPOUL Bd. -

34516 Stanciu Ion Soseaua Oltenitei Nr. 55, Bloc 2, Scara 3, Apt

34516 STANCIU ION SOSEAUA OLTENITEI NR. 55, BLOC 2, SCARA 3, APT. 102, Decizie de impunere 290424 05.03.2021 MUNICIPIUL BUCURESTI, SECTORUL 4, SUB. 10 34517 DUMITRU MARIAN DRUMUL BINELUI NR. 211-213, BLOC VILA A2, MUNICIPIUL Decizie de impunere 214609 05.03.2021 BUCURESTI, SECTORUL 4, SUB. 6 34518 DUMITRU MARIAN DRUMUL BINELUI NR. 211-213, BLOC VILA A2, MUNICIPIUL Decizie de impunere 358763 05.03.2021 BUCURESTI, SECTORUL 4, SUB. 6 34519 DUMITRU MIRELA-ROXANA DRUMUL BINELUI NR. 211-213, BLOC VILA A2, MUNICIPIUL Decizie de impunere 281881 05.03.2021 BUCURESTI, SECTORUL 4, SUB. 6 34520 ZANFIROAIA CLAUDIA STRADA RAUL SOIMULUI NR. 4, BLOC 47, SCARA 5, ETAJ Decizie de impunere 303649 05.03.2021 2, APT. 69, MUNICIPIUL BUCURESTI, SECTORUL 4, SUB. 10 34521 DINCA GABRIELA-FLORICA STRADA STRAJA NR. 12, BLOC 52, SCARA 2, ETAJ 5, APT. Decizie de impunere 333194 05.03.2021 96, MUNICIPIUL BUCURESTI, SECTORUL 4, SUB. 10 34522 COVACI CIPRIAN ANDREI STRADA CONSTANTIN BOSIANU NR. 17, BLOC CORP A, Decizie de impunere 314721 05.03.2021 ETAJ 1, APT. 2A, MUNICIPIUL BUCURESTI, SECTORUL 4, SUB. 1 34523 COVACI CIPRIAN ANDREI STRADA CONSTANTIN BOSIANU NR. 17, BLOC CORP A, Decizie de impunere 298736 05.03.2021 ETAJ 1, APT. 2A, MUNICIPIUL BUCURESTI, SECTORUL 4, SUB. 1 34524 ENE ADRIAN-ALEXANDRU STRADA VULTURENI NR. 78, MUNICIPIUL BUCURESTI, Decizie de impunere 375182 05.03.2021 SECTORUL 4, SUB. 10 34525 LEVCHENKO IULIIA SOSEAUA GIURGIULUI NR. 67-77, BLOC E, SCARA 3, APT. Decizie de impunere 298024 05.03.2021 87, MUNICIPIUL BUCURESTI, SECTORUL 4, SUB. -

Bucharest Booklet

Contact: Website: www.eadsociety.com Facebook: www.facebook.com/EADSociety Twitter (@EADSociety): www.twitter.com/EADSociety Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/eadsociety/ Google+: www.google.com/+EADSociety LinkedIn: www.linkedin.com/company/euro-atlantic- diplomacy-society YouTube: www.youtube.com/c/Eadsociety Contents History of Romania ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….3 What you can visit in Bucharest ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..4 Where to Eat or Drink ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….8 Night life in Bucharest ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….9 Travel in Romania ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….....10 Other recommendations …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….11 BUCHAREST, ROMANIA MIDDLE AGES MODERN ERA Unlike plenty other European capitals, Bucharest does not boast of a For several centuries after the reign of Vlad the Impaler, millenniums-long history. The first historical reference to this city under Bucharest, irrespective of its constantly increasing the name of Bucharest dates back to the Middle Ages, in 1459. chiefdom on the political scene of Wallachia, did undergo The story goes, however, that Bucharest was founded several centuries the Ottoman rule (it was a vassal of the Empire), the earlier, by a controversial and rather legendary character named Bucur Russian occupation, as well as short intermittent periods of (from where the name of the city is said to derive). What is certain is the Hapsburg -

LIST of HOSPITALS, CLINICS and PHYSICIANS with PRIVATE PRACTICE in ROMANIA Updated 04/2017

LIST OF HOSPITALS, CLINICS AND PHYSICIANS WITH PRIVATE PRACTICE IN ROMANIA Updated 04/2017 DISCLAIMER: The U.S. Embassy Bucharest, Romania assumes no responsibility or liability for the professional ability or reputation of, or the quality of services provided by the medical professionals, medical facilities or air ambulance services whose names appear on the following lists. Names are listed alphabetically, and the order in which they appear has no other significance. Professional credentials and areas of expertise are provided directly by the medical professional, medical facility or air ambulance service. When calling from overseas, please dial the country code for Romania before the telephone number (+4). Please note that 112 is the emergency telephone number that can be dialed free of charge from any telephone or any mobile phone in order to reach emergency services (Ambulances, Fire & Rescue Service and the Police) in Romania as well as other countries of the European Union. We urge you to set up an ICE (In Case of Emergency) contact or note on your mobile phone or other portable electronics (such as Ipods), to enable first responders to get in touch with the person(s) you designated as your emergency contact(s). BUCHAREST Ambulance Services: 112 Private Ambulances SANADOR Ambulance: 021-9699 SOS Ambulance: 021-9761 BIOMEDICA Ambulance: 031-9101 State Hospitals: EMERGENCY HOSPITAL "FLOREASCA" (SPITALUL DE URGENTA "FLOREASCA") Calea Floreasca nr. 8, sector 1, Bucharest 014461 Tel: 021-599-2300 or 021-599-2308, Emergency line: 021-962 Fax: 021-599-2257 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.urgentafloreasca.ro Medical Director: Dr. -

Component 1. Elaboration of Bucharest's Iuds, Capital

ROMANIA Reimbursable Advisory Services Agreement on the Bucharest Urban Development Program (P169577) COMPONENT 1. ELABORATION OF BUCHAREST’S IUDS, CAPITAL INVESTMENT PLANNING AND MANAGEMENT Output 3. Urban context and identification of key local issues and needs, and visions and objectives of IUDS and Identification of a long list of projects. Chapter 3. Spatial and Functional Profile March 2021 DISCLAIMER This report is a product of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/the World Bank. The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed in this paper do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of the World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. This report does not necessarily represent the position of the European Union or the Romanian Government. COPYRIGHT STATEMENT The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable laws. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with the complete information to either: (i) the Municipality of Bucharest (Bd. Regina Elisabeta 47, Bucharest, Romania); or (ii) the World Bank Group Romania (Str. Vasile Lascăr 31, et. 6, Sector 2, Bucharest, Romania). This report was delivered in March 2021 under the Reimbursable Advisory Services Agreement on the Bucharest Urban Development Program, concluded between the Municipality of Bucharest and the -

Progresul Tehnic 9

ÎN CINSTEA CONGRESULUI PARTIDULUI Citiți Hunedoara : pagina SENTIMENTUL RAPORT DE ÎNTRECERE a lli-a: MATURIZĂRII !*■................. ...... ............ ....................................... — Proletari din toate țările, uniți-vă 1 OBIECTIV PRINCIPAL: • GALAȚI GALAȚI, (de la corespondentul nostru): — Zilele ffcestea, colectivele de muncitori, tehnicieni și ingi PROGRESUL neri din Întreprinderile industriale ale orașului Galați, au raportat Îndeplinirea angajamentelor luate cinteia In cinstea celui de al IV-lea Congres al partidului. Astfel, de la Începutul anului și pînă în prezent s-a realizat peste sarcina de plan o producție glo bală de 32 172 000 Iei fală de 25 285 000 lei cit pre TEHNIC vedea angajamentul. De asemenea, a fost Îndepli nit angajamentul la producția marfă. Productivitatea muncii a crescut în primele 6 luni din acest an cu Am solicitat tovarășului 3,3 la sută iar economiile la prețul de cost depă șesc 7 000 000 lei. Tot în această perioadă au iost ing. CONSTANTIN NĂCUJÂ tinerelului produse și livrate peste prevederile planului 1 080 tone de tablă subfire, 530 tone sirmă, 166 tone piese turnate din fontă, mari cantități de minereu sortat, adjunct al ministrului industriei construcțiilor de Organ Central al Uniunii Tineretului Muncitor 310 tone uleiuri și grăsimi vegetale și altele. O con mașini, să ne prezinte principalele realizări tribuție de seamă In obținerea acestor succese au :------------------------------------------------------------- adus-o colectivele de muncă de la Uzina Laminorul obținute in ultimii -

Soil Mite Communities (Acari: Mesostigmata) As Indicators of Urban Ecosystems in Bucharest, Romania M

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Soil mite communities (Acari: Mesostigmata) as indicators of urban ecosystems in Bucharest, Romania M. Manu1,5*, R. I. Băncilă2,3,5, C. C. Bîrsan1, O. Mountford4 & M. Onete1 The aim of the present study was to establish the efect of management type and of environmental variables on the structure, abundance and species richness of soil mites (Acari: Mesostigmata) in twelve urban green areas in Bucharest-Romania. Three categories of ecosystem based upon management type were investigated: protected area, managed (metropolitan, municipal and district parks) and unmanaged urban areas. The environmental variables which were analysed were: soil and air temperature, soil moisture and atmospheric humidity, soil pH and soil penetration resistance. In June 2017, 480 soil samples were taken, using MacFadyen soil core. The same number of measures was made for quantifcation of environmental variables. Considering these, we observed that soil temperature, air temperature, air humidity and soil penetration resistance difered signifcantly between all three types of managed urban green area. All investigated environmental variables, especially soil pH, were signifcantly related to community assemblage. Analysing the entire Mesostigmata community, 68 species were identifed, with 790 individuals and 49 immatures. In order to highlight the response of the soil mite communities to the urban conditions, Shannon, dominance, equitability and soil maturity indices were quantifed. With one exception (numerical abundance), these indices recorded higher values in unmanaged green areas compared to managed ecosystems. The same trend was observed between diferent types of managed green areas, with metropolitan parks having a richer acarological fauna than the municipal or district parks. -

Autobuze.Pdf

OTOPENI 780 783 OSTRATU R441 OTOPENI R442 PERIS R443 PISCU R444 GRUIU R446 R447 MICSUNESTII MARI R447B MOARA VLASIEI R448 SITARU 477 GREENFIELD STRAULESTI 204 304 203 204 Aleea PrivighetorilorJOLIE VILLE BANEASA 301 301 301 GREENFIELD 204 BUFTEA R436 PIATA PRESEI 304 131 Str. Jandarmeriei261 304 STRAULESTI Sos. Gh. Ionescu COMPLEX 261 BANEASA RETEAUA DE AUTOBUZE 204 205 304 Sisesti 205 131 261 335 BUFTEA GRADISTEA SITARU R402 R402 261 205 R402 R436 Bd. OaspetilorStr. Campinita 361 605 112 205 261 COMPLEX 131 261301 Sos. Bucuresti Ploiesti COMERCIAL CARTIER 231 Sos. Chitilei Bd. Bucu Sos. Straulesti R447 R447B R448 R477 COLOSSEUM 203 335 361 605 780 783 Bd.R441 R442 R443 R444HENRI R446 COANDA 231 112 Aerogarii R402 605 231 112 112 CARTIER 112 301 112 restii Noi DAMAROAIA 131 R436 335 231 Sos. Chitilei R402 331 R436 CFR 112 CONSTANTA CARTIER MERII PETCHII R409 112 Str. N. Caramfil R402 Bd. Laminorului AUTOBAZA ANDRONACHE 331 112 135 243 Str. Jiului Bd. NORDULUI112 301 382 Sos. Chitilei 605 Sos. 112Pipera 135 Poligrafiei 231 243 Str. Peris 780 783 331 PIATA Str.Oi 243 382 Sos. Bucuresti Ploiesti 243 382 R447PRESEI R447BR448 R477 112 231 243 243 131 203 205 261 304 135 343 105 203 231 tuz CARTIER 261 304 330 361 605 231R441 361 R442 783 R443 R444 R446 Bd. Marasti GIULESTI-SARBI 162 R441 R442 R443 r a lo c i s Bd. Expozitiei231 330 r o a dronache 162 163 105 780 R444 R446t e R409 243 343 Str. Sportului a r 105 i CLABUCET R447 o v l F 381 R448 A . -

Ingineria Aeronautica Romaneasca Si Principalele Contributii Ale Acesteia La Progresul Aviatiei

“Putine natii din lume se pot mandri ca au contribuit la progresul aviatiei , cat a reusit natia romana…” Henri Coanda Ingineria aeronautica romaneasca si principalele contributii ale acesteia la progresul aviatiei de Atomei Adrian ? Cuprins: Prefata 1. Zborul-ispita, legenda, realitate 2. Inceputul aviatiei romanesti cu Vuia, Vlaicu si Coanda? 3. Nasterea industriei aeronautice romanesti(perioada dintre cele doua razboaie) 4. Industria romaneasca-postbelica de aviatie 5. Alte contributii romanesti de marca in aviatie Bibliografie ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? Prefata Lucrarea de fata nu se vrea a fi un studiu riguros in ceea ce priveste istoria ingineriei aeronautice romanesti si a contributiilor sale in progresul aviatiei romanesti si internationale totodata, fiindca orice ar spune “gurile rele” Romania va ramane incontestabil una dintre putinele tari care au avut o contributie majora la “inceputul aviatiei”.Aceasta afirmatie nu este o exagerare cum ar fi unii tentati sa creada si nici o “frustare a unui roman ce are credinta ca lumea ignora, pe nedrept, contributiile precursorilor” asa cum mi-a fost dat sa citesc in una din cartile ce le-am avut drept suport pentru lucrarea de fata. Cel mai simplu mod, de a-mi sustine scurta pledoarie ar fi cuvintele lui Elie Carafoli, care spunea: ”Poporul roman se numara printre primele popoare care au participat la aceasta manifestare a geniului omenesc ce avea sa duca in numai jumatate de secol, la o dezvoltare uluitoare a navigatiei aeriene.” Binenteles, Elie Carafoli se -

Leadership Strategies in Promoting the Image of the Mayors on the Web- Sites of Sector Town Halls and of Bucharest City Hall

LEADERSHIP STRATEGIES IN PROMOTING THE IMAGE OF THE MAYORS ON THE WEB- SITES OF SECTOR TOWN HALLS AND OF BUCHAREST CITY HALL Viorica PĂUŞ Viorica PĂUŞ Professor, Department of Cultural Anthropology and Communication, Faculty of Journalism and Mass Communication, University of Bucharest, Bucharest, Romania Tel.: 004-021-318.15.15 E-mail: [email protected] Abstract The research deals with the leadership strategies used by the mayors of the six sectors and the General Mayor of Bucharest in order to represent and promote the organizational image and their own image. The success, performance and competitiveness of sector town halls and Bu- charest City Hall also depend on the quality of leadership and the leaders’ ability to use appro- priate, attractive and customized online commu- nication strategies in order to inform the citizens and achieve their electoral goals. This research has the following objectives: (a) to identify the online strategies used by the seven mayors-leaders; (b) to identify the sa- lience of tactics used by the seven mayors; (c) to identify the ethos categories within the mayors’ online messages. Keywords: local public administration, may- or, open leadership, communication, information, website, effi ciency. Transylvanian Review of Administrative Sciences, No. 47 E/2016, pp. 146-163 146 1. Introduction Leadership should not be strictly associated with multinational corporations and it should not exclusively refer to the employer-employee relationship. Mayors are a special category of leaders. Besides their internal communication within the city or town halls, they are elected by citizens and thus they should build solid relationships with the inhabitants as well. -

Carte Andronic 7 Day 2015.QXP Layout 1

AMOS News * saptezile, Coperta : Jean Vasilescu Tehnoredactare: Cristian Negoi Prelucrare imagini: Ana Ştefania Andronic Descrierea CIP a Bibliotecii Naţionale a României AMOS, News șaptezile / AMOS News - Bucureşti : Semne, 2016 ISBN Toate drepturile şi responsabilităţile asupra conţinutului aparţin Fundaţiei AlegRO Editura SEMNE Str. Barbu Delavrancea nr. 24 Sector 1, Bucureşti Tel./Fax: 021 318 83 44 email: [email protected] web: www.semneartemis.ro Comenzi: Tel: 0724 239 358 [email protected] www.fundatia-aleg.ro Tiparul executat la S.C. SEMNE ‘94 SRL Tel./Fax: 021 667 08 20 Bucureşti, 2016 AMOS News saptezile, stenogramelesăptamânalecomentate aleevenimentelordincelde-al cincisprezeceleaan almileniuluitrei MMXV Fundaţia AlegRO Introducere Douămiicincisprezece Cel de-al treilea volum de stenograme desprinse din actualitatea generală sub genericul „şaptezile” aduce în faţa cititorilor imaginea complexă şi adeseori contra- dictorie a unui an în care s-au întâmplat multe lucruri lipsite de importanţă şi foarte puţine cu consecinţe di- recte asupra evoluţiei spre mai bine a societăţii româneşti. Dincolo de zgomotul de fond afonic al feluritelor dispute se desprinde însă ceea ce a marcat ultima parte a anului: modul în care un incident, precum cel al in- cendiului de la clubul „Colectiv”, s-a repercutat asupra evoluţiilor politice, într-un scenariu desprins parcă din „Scrisoarea pierdută” a lui Caragiale: cum din con- fruntarea dintre PSD-ul aflat la guvernare şi PNL-ul dor- nic să-i ia locul cât mai curând a triumfat acest Dandanache XXI – guvernul Tehnocrat al lui Cioloş. Semnificaţia profundă a evenimentului constă în inca- pacitatea actorilor politici de a determina acele mutaţii pe care societatea le cere şi abandonul laş în faţa imix- tiunilor externe în cursul proceselor interne. -

Removal of Zinc Ions Using Hydroxyapatite and Study of Ultrasound Behavior of Aqueous Media

materials Article Removal of Zinc Ions Using Hydroxyapatite and Study of Ultrasound Behavior of Aqueous Media Simona Liliana Iconaru 1, Mikael Motelica-Heino 2,Régis Guegan 3, Mihai Valentin Predoi 4, Alina Mihaela Prodan 5,6 and Daniela Predoi 1,* 1 National Institute of Materials Physics, Atomistilor Street, No. 405A, P.O. Box MG 07, Magurele 077125, Romania; [email protected] 2 Institut des Sciences de la Terre d’Orléans (ISTO), UMR 7327 CNRS Université d’Orléans, 1A rue de la Férollerie, 45071 Orléans CEDEX 2, France; [email protected] 3 Faculty of Science and Engineering, Global Center for Science and Engineering, Waseda University, 3-4-1, Okubo, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo 169-8555, Japan; [email protected] 4 Department of Mechanics, University Politehnica of Bucharest, BN 002, 313 Splaiul Independentei, Sector 6, Bucharest 060042, Romania; [email protected] 5 Emergency Hospital Floreasca Bucharest, 8 Calea Floreasca, Sector 1, Bucharest 014461, Romania; [email protected] 6 Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy, 8 Eroii Sanitari, Sector 5, Bucharest 050474, Romania * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +40-212418154 Received: 6 June 2018; Accepted: 1 August 2018; Published: 3 August 2018 Abstract: The present study demonstrates the effectiveness of hydroxyapatite nanopowders in the adsorption of zinc in aqueous solutions. The synthesized hydroxyapatites before (HAp) and after the adsorption of zinc (at a concentration of 50 mg/L) in solution (HApD) were characterized using X-ray diffraction (XRD), and scanning and transmission electron microscopy (SEM and TEM, respectively). The effectiveness of hydroxyapatite nanopowders in the adsorption of zinc in aqueous solutions was stressed out through ultrasonic measurements.