A Modest Plant, Easily Crushed Radio Drama in Blin, Eritrea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Appraisal of the Current Status and Potential of Surface Water in the Upper Anseba Catchment

An Appraisal of the Current Status and Potential of Surface Water in the Upper Anseba Catchment Abraham Daniel Filimon Tesfaslasie Selamawit Tefay 2009 An Appraisal of the Current Status and Potential of Surface Water in the Upper Anseba Catchment Abraham Daniel Filmon Tesfaslasie Selamawit Tesfay 2009 This study and the publication of this report were funded by Eastern and Southern Africa Partnership Programme (ESAPP). Additional financial and logistic support came from CDE (Centre for Development and Environment), Bern, Switzerland within the framework of Sustainable Land Management Programme, Eritrea (SLM Eritrea). ii CONTENTS Tables, Figures and Maps Abbreviations and Acronyms Foreward Acknowledgement Executive Summary 1 BACKGROUND 1 1.1 Maekel Zone 1.2 Description of the study area 1.2.1 Topography 1.2.2 Vegetation 1.2.3 Soils 1.2.4 Geology 1.2.5 Climate 1.2.6 Land use land cover and Land tenure 1.2.7 Water resources 1.2.8 Farmers’ association and extension services 1.3 Problem Statement 1.4 Objectives of the study 1.4.1 Specific Objectives 2 METHODOLOGY 21 2.1 Site Selection 2.2 Literature review and field survey 2.3 Remote Sensing and GIS data analyses 2.4 Estimating actual reservoir capacity and sediment deposition 2.5 Qualitative data collection 2.6 Awareness creation 3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION 27 3.1 Catchment reservoir capacity and current reservated water 3.1.1 Reservoirs 3.1.1.1 Distribution 3.1.1.2 Reservoirs age and implementing agencies 3.1.1.3 Characteristics of Dam bodies 3.1.1.4 Catchment areas 3.1.2 Reservoir capacity -

UNDP ERITREA NEWSLETTER Special Edition ©Undperitrea/Mwaniki

UNDP ERITREA NEWSLETTER Special Edition ©UNDPEritrea/Mwaniki UNDP Staff in Asmara, Eritrea In this Issue 3. New UN Secretary General Cooperation Framework 10. Ground breaking 6. Eritrean Students receive 2017-2015. International Conference 708 bicycles from Qhubeka 8. International Day for the on Eritrean Studies held in Asmara 7. Government of the Eradication of Poaverty State of Eritrea and the marked in Eritrea 11. Fifty years of development, United Nations launch 9. International Youth Day Eritrea celebrates UNDP’s the Strategic Partnership celebration in Eritrea 50th anniversary Message from the Resident Representative elcome to our special edition of the UNDP Eritrea annual newsletter. In this special edition, we shareW with our partners and the public some of our stories from Eritrea. From the beginning of this year, we embarked on a new Country Programme Document (CPD) and a new Strategic Partnership Cooperation Framework (SPCF) between the UN and The Government of the State of Eritrea. Both documents will guide our work until 2021. In February 2017, we partnered with the Ministry of Education, Qhubeka, Eritrea Commission of Culture and Sports and © UNDP Eritrea/Mwaniki the 50 mile Ride for Rwanda to bring 708 bicycles to students in Eritrea. This UNDP Eritrea RR promoting the SDGs to mark the 50th Anniversary initiative is an education empowerment program in Eritrea that has been going Framework (SPCF) 2017 – 2021 between In 2017, I encourage each one of us to on for 2 years. the UN and the Government of the State reflect on our successes and lessons of Eritrea. learned in the previous years. -

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome

SPECIAL REPORT FAO/WFP CROP AND FOOD SUPPLY ASSESSMENT MISSION TO ERITREA 18 January 2005 Mission Highlights • Successive years of drought and inadequate rains have seriously undermined crop and livestock production in Eritrea. • In 2004, Azmera rains (March-May), important for land preparation and replenishment of pastures, in key agricultural areas failed and the main Kremti rains (June-September) were late and ended early. • As a result, cereal production in 2004 is forecast at about 85 000 tonnes, less than half the average of the previous 12 years. • Pastoralists were seriously affected by the delayed rains, which resulted in early migration of livestock in parts. Serious feed shortages are expected in early 2005 in several parts of the country. • The cereal import requirement for 2005 is estimated at 422 000 tonnes of which about 80 000 tonnes are anticipated to be imported commercially. • With 80 000 tonnes of food aid pledged and in the pipeline, the uncovered deficit, for which international assistance is needed, is estimated at 262 000 tonnes. • In 2005, an estimated 2.3 million people, about two-thirds of the whole population - including in urban and peri-urban areas - will require food assistance to varying levels. • Timely support to crop and livestock production is urgently needed to revive production capacity in 2005. Short cycle and early maturing cereal seed varieties need to also be made available in case the apparent pattern of late rains in the last several years materialises. 1. OVERVIEW An FAO/WFP Crop and Food Assessment Mission visited Eritrea from 15 November to 3 December 2004 to estimate the 2004 main season harvest, assess the overall food supply situation and forecast import requirements for 2005, including food assistance needs. -

GEF Country Portfolio Evaluation: ERITREA (1992–2012) December 2014 Final Evaluation Report

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized GEF Country Portfolio Evaluation: ERITREA (1992–2012) December 2014 Final Evaluation Report Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Country Portfolio Evaluation: Eritrea Report – December 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword and Acknowledgements ................................................................................................. 4 1. Main Conclusions and Recommendations .................................................................................. 6 1.1 Background 6 1.2 Objectives, Scope and Methodology 7 1.3 Limitations 11 1.4 Conclusions 12 1.5 Recommendations 23 2. Evaluation Framework .............................................................................................................. 25 2.1 The Global Environment Facility 25 2.2 Background 25 2.3 Objectives 26 2.4 Scope 27 2.5 Methodology and Approach 27 2.6 Limitations 29 3. Context of the Evaluation ......................................................................................................... 30 3.1 Eritrea: Country Context 30 3.2 Environmental Resources in Key GEF Support Areas 32 3.3 The Environmental Institutional, Policy and Legal Framework in Eritrea 40 4. The GEF Portfolio in Eritrea .................................................................................................... 52 4.1 Defining the GEF Portfolio 52 4.2 Activities in the GEF Portfolio 53 4.3 GEF Support by Implementing Agency 55 4.4 GEF Support by Focal Area 56 4.5 Small Grants Programme (SGP) 59 -

Eritrea Health Update Issue 3 No

Eritrea Health Update Issue 3 No. 3 10th March – 16th March, 2008 Outbreak Monitoring: Week 11 (10th March – 16th March, 2008) PROFILES ) Eritrea Population: Report on Completeness is maintained at an 3,543,580 - (1997 and Timeliness appreciable level, there is an Projection) unprecedented delay in the ll six Zobas/Regions submission of weekly Number of Zobas submitted reports up reports from the (Regions): 6 Ato week 11. The zoba/regional health offices Southern Red Sea to the central Ministry of Humanitarian and Gash Baka Health. A mechanism Zobas/Regions continue to therefore has to be put in Target population: record the lowest place to facilitate the timely 2.3 Million percentages in terms of submission of reports from timeliness of reporting. the zoba/regional level to Sources of There is a need to work with the central Ministry of humanitarian these two regional health Health. funding: offices to improve the • UN CERF timeliness of reporting. Cerebro-Spinal Meningitis • EU-ECHO (CSM) Although the average To date, there has been no • DFID timeliness of reporting from newly suspected case of the health facilities to the meningitis recorded in 2008 HIGHLIGHTS zoba/regional health offices from any of the zones. Table 1: Average Health facility to Zoba weekly report completeness and Outbreak monitoring timeliness as at week 11(10th – 16th March, 2008) for week 11 Measles and AFP Zoba Total Population Number of HFs Timeliness Completeness Surveillance Anseba 570079 34 Indicators for the First 97.79 100 Quarter in 2008 Debub 942128 60 98.66 99.25 Rapid Assessment Gash Barka 704151 65 57.30 92.70 Mission Report to the Maekel 671941 31 Southern Red Sea 97.66 100 Zone NRS 572546 37 75.42 92.14 SRS 82735 15 38.79 87.88 ERITREA HEALTH Total 3,543,580 242 96.79 80.27 UPDATE Eritrea Health Update c/o WHO, Adi Yakob street N. -

Proposal for Eritrea

AFB/PPRC.4/6 March 2, 2011 Adaptation Fund Board Project and Programme Review Committee Fourth Meeting Bonn, March 16, 2011 PROPOSAL FOR ERITREA I. Background 1. The Operational Policies and Guidelines for Parties to Access Resources from the Adaptation Fund, adopted by the Adaptation Fund Board, state in paragraph 41 that regular adaptation project and programme proposals, i.e. those that request funding exceeding US$ 1 million, would undergo either a one-step, or a two-step approval process. In case of the one- step process, the proponent would directly submit a fully-developed project proposal. In the two- step process, the proponent would first submit a brief project concept, which would be reviewed by the Project and Programme Review Committee (PPRC) and would have to receive the approval by the Board. In the second step, the fully-developed project/programme document would be reviewed by the PPRC, and would finally require Board’s approval. 2. The Templates Approved by the Adaptation Fund Board (Operational Policies and Guidelines for Parties to Access Resources from the Adaptation Fund, Annex 3) do not include a separate template for project and programme concepts but provide that these are to be submitted using the project and programme proposal template. The section on Adaptation Fund Project Review Criteria states: For regular projects using the two-step approval process, only the first four criteria will be applied when reviewing the 1st step for regular project concept. In addition, the information provided in the 1st step approval process with respect to the review criteria for the regular project concept could be less detailed than the information in the request for approval template submitted at the 2nd step approval process. -

Irrigation Development in Eritrea: Potentials and Constraints

AEAS / ESAPP / SLM Eritrea Joint Report Irrigation Development in Eritrea: Potentials and Constraints Proceedings of the Workshop of the Association of Eritreans in Agricultural Sciences (AEAS) and the Sustainable Land Management Programme (SLM) Eritrea 14 – 15 August 2003 Asmara, Eritrea Editors: Tadesse Mehari and Bissrat Ghebru 2005 A ESAPP E A S Irrigation Development in Eritrea: Potentials and Constraints Irrigation Development in Eritrea: Potentials and Constraints Proceedings of Workshop of the Association of Eritreans in Agricultural Sciences (AEAS) and the Sustainable Land Management Programme (SLM) Eritrea Editors: Tadesse Mehari and Bissrat Ghebru Publisher: Geographica Bernensia Berne, 2005 Citation: Tadesse Mehari and Bissrat Ghebru (Editors) 2005 Irrigation Development in Eritrea: Potentials and Constraints. Proceedings of the Workshop of the Association of Eritreans in Agricultural Sciences (AEAS) and the Sustainable Land Management Programme (SLM) Eritrea, 14-15 August 2003, Asmara Berne, Geographica Bernensia, 150pp. SLM Eritrea, and ESAPP, Syngenta Foundation for Sustainable Agriculture, and Centre for Development and Environment (CDE), University of Berne, 2005 Publisher: Geographica Bernensia Printed by: Victor Hotz AG, CH-6312 Steinhausen, Switzerland Copyright© 2005 by: Association of Eritreans in Agricultural Sciences (AEAS), and Sustainable Land Management Programme (SLM) Eritrea This publication was prepared with support from: Syngenta Foundation for Sustainable Agriculture, Basle, and Eastern and Southern Africa Partnership Programme (ESAPP) English language editing: Tadesse Mehari and Bissrat Ghebru Layout: Simone Kummer, Centre for Development and Environment (CDE), University of Berne Maps: Brigitta Stillhardt, Kurt Gerber, Centre for Development and Environment (CDE), University of Berne Copies of this report can be obtained from: Association of Eritreans in Agricultural Tel ++291 1 18 10 77 Sciences (AEAS), Fax ++291 1 18 14 15 P.O. -

Eritrean Agriculture and Its Emergence in Accordance with The

Munich Personal RePEc Archive EMERGING ERITREAN AGRICULTURE IN ACCORDANCE WITH GLOBAL COMPETITION: A CASE STUDY ON ELABERED ESTATE Rena, Ravinder Department of Business and Economics, Eritrea Institute of Technology, Mai Nefhi, Eritrea 25 August 2003 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/10317/ MPRA Paper No. 10317, posted 07 Sep 2008 06:24 UTC Rena, Ravinder (2004) “Emerging Eritrean Agriculture in Accordance with Global Competition: A Case Study on Elabered Estate”, Hyderabad(India): Osmania Journal of Social Sciences, Vol.4, No. 1& 2. pp. 34-44. (A Biannual Journal Published by the Faculty of Social Sciences, Osmania University). EMERGING ERITREAN AGRICULTURE IN ACCORDANCE WITH GLOBAL COMPETITION: A CASE STUDY ON ELABERED ESTATE - RAVINDER RENA∗ I. INTRODUCTION This paper explores the Eritrean agricultural production, land and people. It also provides the Elabered Estate, how it increases agricultural yields through using varieties of grains with greater resistance to disease and pests, together with the use of improved farm management techniques and chemical inputs, such as improved pesticides and fertilizers. Thus present paper covers the success story of Elabered Estate of an important player in Eritrean agriculture sector. The paper deals with the concerted efforts made by the Estate to go with the Global Competition. It also highlights some of the problems and challenges of Eritrean agriculture sector. Agriculture is the key sector in most developing countries. It has a key role to play in enabling them to accomplish developmental goals, including self-reliance, growth and equity. Food production is a fundamental problem is many developing countries including Eritrea. The critical need for increasing food production in developing countries like Eritrea is through modern technology. -

Profile of Internal Displacement : Eritrea

PROFILE OF INTERNAL DISPLACEMENT : ERITREA Compilation of the information available in the Global IDP Database of the Norwegian Refugee Council (as of 19 October, 2001) Also available at http://www.idpproject.org Users of this document are welcome to credit the Global IDP Database for the collection of information. The opinions expressed here are those of the sources and are not necessarily shared by the Global IDP Project or NRC Norwegian Refugee Council/Global IDP Project Chemin Moïse Duboule, 59 1209 Geneva - Switzerland Tel: + 41 22 788 80 85 Fax: + 41 22 788 80 86 E-mail : [email protected] CONTENTS CONTENTS 1 PROFILE SUMMARY 6 SUMMARY 6 SUMMARY 6 CAUSES AND BACKGROUND OF DISPLACEMENT 9 MAIN CAUSES FOR DISPLACEMENT 9 ARMED CONFLICT BETWEEN ERITREA AND ETHIOPIA CAUSED SUBSTANTIAL INTERNAL DISPLACEMENT (MAY 1998 - JUNE 2000) 9 BACKGROUND OF THE CONFLICT 10 BACKGROUND TO THE BORDER DISPUTE (1999) 10 CHRONOLOGY OF THE MILITARY CONFRONTATIONS IN BORDER AREAS BETWEEN ERITREA AND ETHIOPIA (MAY 1998 – JUNE 2000) 11 END OF WAR AFTER SIGNING OF CEASE-FIRE IN JUNE 2000 AND PEACE AGREEMENT IN DECEMBER 2000 13 THE UNITED NATIONS MISSION IN ETHIOPIA AND ERITREA (UNMEE) AND THE TEMPORARY SECURITY ZONE (TSZ) 16 POPULATION PROFILE AND FIGURES 19 TOTAL NATIONAL FIGURES 19 BETWEEN 50,000-70,000 PEOPLE REMAINED INTERNALLY DISPLACED BY MID-2001 19 AVAILABLE FIGURES SUGGEST THAT 308,000 REMAINED INTERNALLY DISPLACED BY END-2000 20 APPROXIMATELY 900,000 ERITREANS INTERNALLY DISPLACED BY MID-2000 21 THE IDP POPULATION ESTIMATED TO AMOUNT TO 266,200 BY THE -

They Are Making Us Into Slaves, Not Educating Us” How Indefinite Conscription Restricts Young People’S Rights, Access to Education in Eritrea

HUMAN “They Are Making Us into Slaves, RIGHTS Not Educating Us” WATCH How Indefinite Conscription Restricts Young People’s Rights, Access to Education in Eritrea “They Are Making Us into Slaves, Not Educating Us” How Indefinite Conscription Restricts Young People’s Rights, Access to Education in Eritrea Copyright © 2019 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-37526 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org AUGUST 2019 ISBN: 978-1-6231-37526 “They Are Making Us into Slaves, Not Educating Us” How Indefinite Conscription Restricts Young People’s Rights, Access to Education in Eritrea Summary ......................................................................................................................... 1 “Sawa” as a Recruitment Channel ............................................................................................. -

GIEWS Country Brief Eritrea

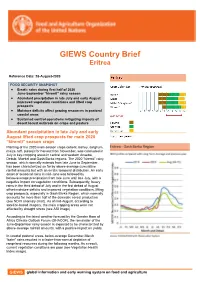

GIEWS Country Brief Eritrea Reference Date: 28-August-2020 FOOD SECURITY SNAPSHOT Erratic rains during first half of 2020 June-September “kiremti” rainy season Abundant precipitation in late July and early August improved vegetation conditions and lifted crop prospects Moisture deficits affect grazing resources in pastoral coastal areas Sustained control operations mitigating impacts of desert locust outbreak on crops and pasture Abundant precipitation in late July and early August lifted crop prospects for main 2020 “kiremti” season crops Planting of the 2020 main season crops (wheat, barley, sorghum, maize, teff, pulses) for harvest from November, was concluded in July in key-cropping areas in central and western Anseba, Debub, Maekel and Gash Barka regions. The 2020 “kiremti” rainy season, which normally extends from late June to September, has been characterized so far by above-average cumulative rainfall amounts but with an erratic temporal distribution. An early onset of seasonal rains in mid-June was followed by below-average precipitation from late June until late July, with a negative impact on vegetation conditions. Subsequently, heavy rains in the third dekad of July and in the first dekad of August offset moisture deficits and improved vegetation conditions, lifting crop prospects, especially in Gash Barka Region, which normally accounts for more than half of the domestic cereal production (see NDVI anomaly chart). As of mid-August, according to satellite-based imagery, the main cropping areas were not affected by drought stress (see ASI image). According to the latest weather forecast by the Greater Horn of Africa Climate Outlook Forum (GHACOF), the remainder of the June-September rainy season is expected to be characterized by above-average rainfall amounts, with a positive impact on yields. -

Where Are They? Eritrea’S Disappeared Page | 2

Eritrea’s Disappeared Page | 1 Where Are They? Eritrea’s Disappeared Page | 2 Political Prisoners, Prisoners of Conscience and Other Forcibly Disappeared Citizens in Eritrea August 2020 Revised Eritrea’s Disappeared Eritrea’s Disappeared Page | 1 Remembering is an act of defiance Eritrea’s Disappeared Page | 1 Disappearances in 1991 On 17 July 1991, barely seven weeks after liberation day, state security arrested Mohammed Maranet and took him to an undisclosed location, not to be heard from again. Thus began the plight of one family in Keren for which the dark side of our post- Disappeared Independence reality unfolded much sooner than in 1991 for many of us. Nearly 30 years on, his children, now grown up men and women, and their bereaved mother, are still waiting for answers. Mohammed Maranet, born on the banks of Anseba river in a village north of Keren, was a teacher at Keren Ma’had, the Islamic school Mohammed Maranet –– attached to the main mosque, from 1970 to 1985. Thereafter, and up Teacher, judge. Abducted by to the day of his disappearance, he served as a judge (qadi) in Keren, the Isaias regime on Ghindae and Agordat. 17/07/1991 and still missing Maranet was not new to incarceration. In 1969, in his final year as a student, he was arrested at the main bus station in Keren, moments THE FIRST ERITREAN PRISONER OF CONSCIENCE after receiving a letter from the Eritrean Liberation Front (ELF) secretly AFTER INDEPENDENCE delivered to him. He was subsequently sentenced to 1 year in prison which he spent at ‘Karsheli’ in Asmara.