By Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Theology, Acadia Divinity College

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Academic Calendar 2019-2020

125 1894 - 2019 Academic Calendar 2019-2020 Published by the Office of the Registrar Tyndale University College & Seminary 3377 Bayview Avenue Toronto, Ontario M2M 3S4 Message from the Academic Dean When you study at Tyndale Seminary, you are immersed in a vibrantly diverse community of faith and learning. We hope that being part of this unique and inspiring community will be one of the most transformative experiences of your life. Our programs are designed to stretch you intellectually, invigorate you spiritually and provide you with skills for ministry and service. We invite you to engage wholeheartedly in the Tyndale community as you become equipped for effective and faithful participation in Dr. Janet Clark the mission of God in this world. The faculty and staff of Tyndale count it a privilege to be your companions on this exciting journey of faith and learning. Grace and Peace, Janet L. Clark, PhD Senior Vice President Academic & Dean of the Seminary Academic Calendar 3 Table of Contents Message from the Academic Dean ...................................3 Campus Information . 7 Important Dates ..................................................8 Profile . .10 About Tyndale ...................................................10 Mission Statement . 10 The Tyndale Crest . .10 Statement of Faith . .11 History . .12 Outline of Institutional Heritage . .13 Academic Freedom . .14 Divergent Viewpoints . .16 About Tyndale Seminary ..........................................18 Introduction. .18 Theological Identity . .18 Theological Education . .19 Faculty . .20 Statement on Women and Men in Ministry. 20 Flexible Course Scheduling . .21 Affiliations and Associations . .21 Centres and Continuing Education Resources. 23 Admissions .....................................................25 General Information. 25 Admission Information and Procedures . 28 Special Admission. 32 Application Deadlines. 33 Policies for Specific Programs. -

Uncommon Vision

Uncommon Vision Tyndale in Depth • 2007 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ................................................Page1 Profile ....................................................Page1 Educational Philosophy .......................................Page3 Goals .....................................................Page4 Christian University Education ..................................Page5 Why Tyndale ...............................................Page7 Why Toronto ...............................................Page8 New Programs ..............................................Page9 Academic Planning...........................................Page11 Future Space Requirements ....................................Page13 Enrollment Projections ........................................Page14 Funding ...................................................Page15 Leadership .................................................Page17 Faculty ....................................................Page19 Governance ................................................Page23 INTRODUCTION & PROFILE Introduction Tyndale: A heart to shape the world Tyndale provides graduate programs Tyndale’s Graduates Tyndale History The graduate school—Tyndale Seminary—is among the Tyndale graduates are employed in many sectors of the 1894 – Toronto Bible Training School (TBTS) opened in Tyndale University College & Seminary is an exciting and largest seminaries in North America. With a vision to marketplace, both locally and globally, including church downtown Toronto. innovative centre -

Dr. Keith Churchill and Dr. Dennis Veinotte

Establishing Scholarships in honour of Dr. Keith Churchill and Dr. Dennis Veinotte Clark Commons, Acadia University Wolfville, Nova Scotia Thursday, October 11, 2018 12 noon Scholarships G. Keith Churchill Scholarship of Worship Income from a trust fund established by David and Faye Huestis of Saint John, New Brunswick, in recognition of the outstanding church leadership of Rev. Dr. G. Keith Churchill. First preference to a student who shows evidence of understanding the theology, history, and conduct of worship in its traditional and contemporary forms. Recipients shall demonstrate aptitude, potential, and financial need. Dennis M. Veinotte Scholarship of Pastoral Counselling and Hospital Chaplaincy Income from a trust fund established by David and Faye Huestis of Saint John, New Brunswick, in recognition of the exceptional pastoral care and counselling ministry of Rev. Dr. Dennis M. Veinotte. First preference to a student who shows evidence of commitment to the ministry of pastoral counselling or chaplaincy. Recipients shall demonstrate aptitude, potential, and financial need. 2 Program Welcome and Opening Remarks Rev. Dr. Harry G. Gardner, President, Acadia ’77 Table Grace Rev. Edward (Ted) Britten, Acadia ’61, ’64 Buffet Lunch Welcome to David (Acadia ’63) and Faye Huestis Thomas J. Rice, ADC Board of Trustees, Acadia ’79 Greetings and Purpose of Scholarships David Huestis Remembering Rev. Dr. G. Keith Churchill, Acadia ’61 David Huestis Rev. Dr. Carol Anne Janzen, Acadia ’71, ’95 Response Joan Churchill Appreciation Faye Huestis Special Musical Selection: Be Thou My Vision Barry Snodgrass, Saint John, New Brunswick Accompanist Anne Huestis Scott, Acadia ’67 Remembering Rev. Dr. Dennis M. Veinotte, Acadia ’59, ’62, ’80 David Huestis George Lohnes, Q.C. -

Dmin Self-Study Church Or Ministry

15 University Avenue Wolfville, Nova Scotia Canada B4P 2R6 Telephone: (902) 585-2210 Fax: (902) 585-2233 www.acadiadiv.ca DMIN SELF-STUDY CHURCH OR MINISTRY We are currently considering an application from _________________________ to the Acadia Doctor of Ministry program. The Doctor of Ministry degree is an “in-ministry” degree that is designed to benefit both the applicant and the church or ministry they serve. The Acadia D.Min. program is a select, limited admission program designed for effective vocational ministry leaders. A key component to evaluating an application is the self- study completed by the church or ministry. Please carefully answer each of the following questions in 500 words or less, using single spacing, 12 point, Times New Roman font. 1. Does the applicant have the support of the leadership of your church or ministry for undertaking the Doctor of Ministry program? How do you see the four years of study benefiting your church or ministry? 2. Comment on the applicant’s leadership style and ability, ministry gifts, and fit within your church or ministry, and how his or her leadership has helped advance this ministry. 3. Comment on the following qualities as they relate to the applicant: ability to work with others, willingness to take direction, ability to communicate, organizational ability, sense of responsibility, personal initiative, and emotional stability. Respondent’s name: Ministry or church name: Your position in this ministry or church: Your phone number: Your email address: Confidential: Do not return to the applicant. Please return the completed form to: Acadia Divinity College The Registrar’s Office 15 University Ave. -

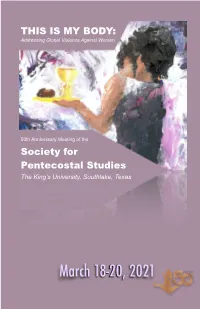

2021 Program

THIS IS MY BODY: Addressing Global Violence Against Women 50th Anniversary Meeting of the Society for Pentecostal Studies The King’s University, Southlake, Texas March 18-20, 2021 INFORMATION AT A GLANCE H OTEL Hyatt Place Dallas/Grapevine 2220 W. Grapevine Mills Circle Grapevine, TX 76051 Phone: 972-691-1199 R EGISTRATION Kim Roebuck Assistant to the SPS Executive Director [email protected] M EMBERSHIP INFORMATION Jesse Heath Secretary/Treasurer [email protected] G ENERAL PROGRAM INFORMATION Adrian Hinkle Executive Director [email protected] F IRST AID In the event that you need minor medical assistance while enjoying the conference, please contact an Interest Group Leader or member of the SPS Executive Committee for assistance. Anyone involved in or observing a major medical need should immediately call 911. TKU’s address is 2121 E. Southlake Blvd. Southlake, TX 76092 SPS | 2021 ANNUAL MEETING 1 W IFI ACCESS Complimentary wifi is available on TKU’s campus during the conference. In order to connect, select “TKU Campus WiFi” P URCHASE SPS PAPERS Interest Group papers are available for purchase. The purchase price of the papers is $35 which will include a pre-conference online access and a cd of papers to be sent in June. Papers received post conference will also be added to the online access and are available beginning May 3, 2021; purchasers will be given a username and password in order to access the papers via this link: www.sps-usa.org/meetings/papers21. C OPYRIGHT NOTICE All papers are copyrighted 2021 by their authors with all rights reserved to the authors. -

Recruitment Coordinator

Recruitment Coordinator The position of Recruitment Coordinator calls for an energetic, organized, and outgoing individual who will actively engage in recruiting students for the various degree, diploma, and certificate programs of Acadia Divinity College (ADC). The Recruitment Coordinator will be responsible for developing and executing a recruitment plan under the leadership of the Director of Advancement and in partnership with the Advancement Team. The incumbent will develop and implement strategies that foster relationships with prospective students, churches, and church leaders. This will include dialogue with prospective students about their call to ministry and exploration of how ADC can equip them to fulfill this calling. This will require significant travel including some weekends. In addition, the incumbent will provide leadership to programs and outreach efforts, promoting ADC, and developing a stream of prospective students for all degree, diploma, and certificate programs. Key Responsibilities Work with the Director of Advancement to create a strategic plan for recruiting students for the Bachelor of Theology, Master of Divinity, Master of Arts (Theology), and Doctor of Ministry degree programs, as well as the diploma and certificate programs. Implement and coordinate student recruitment programs and initiatives, with an initial focus in Atlantic Canada. Foster key relationships with pastors, denominational leaders, and churches to raise the awareness of ADC’s theological training and to identify potential students. Represent ADC at targeted events to raise the profile of the College and make first contacts with prospective students. Journey with prospective students to help and encourage them in the application process. Work with the Advancement Team on the production of recruitment materials and promotional products to be used in recruitment. -

Philo's and Paul's Retelling of the Abraham Narrative in De Abrahamo

Philo’s and Paul’s Retelling of the Abraham Narrative in De Abrahamo and Galatians 3–4 and Romans 4 ID # 260575888 Shekari, Elkanah Kuzahyet-Buki Faculty of Religious Studies (FRS), McGill University, Montreal April, 2015 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts in Religious Studies © Copyright Elkanah Kuzahyet-Buki Shekari, 2015 1 ABSTRACT The Abraham narrative found in Genesis 11:26–25:10 has been retold in different ways by both Jews and non-Jews. All the re-tellers wanted to point out the way in which the Abraham narrative impacted people. The history of research on Abraham in the last century, shows little or no interests in the re-tellers of the Abraham narrative. For example, their primary sources, styles of text selection, and arrangement of the selected data in retelling the story of Abraham. Rather, the history of research shows that scholars were more interested on the reliability of the narrative, the religion of Abraham and his role as the ancestor of the Jews and of the non-Jews. My primary focus is on Philo’s and Paul’s retelling of the Abraham narrative, their primary source; their selection from the source; their arrangement of the events, and their goals for retelling the story of Abraham. I used the insights of producing history of Hayden White, a literary critic and philosopher of history. White’s insights show how historians select from their primary sources by means of their plot-structure, in order to retell past events by means of the historians emplotment, argument, ideological implications, and use of figurative language (tropes). -

President of Acadia Divinity College and Dean of Theology

President of Acadia Divinity College and Dean of Theology Acadia Divinity College invites applications for a full-time President of Acadia Divinity College and Dean of Theology. Position Summary The President of Acadia Divinity College (ADC) and Dean of Theology at Acadia University is a spiritually grounded academic and visionary leader who collaboratively guides the College in its mission to “equip Christian leaders for full-time and voluntary ministry in Canada and the world.” The President / Dean serves in an environment that places students at the centre of the educational experience, equipping them to lead with passion, purpose, skills, and knowledge to serve the mission of the Christian church in the reality of ever-changing cultures. The President / Dean ensures that Acadia Divinity College has the financial resources, facilities, equipment, and investments to accomplish its mission and meet its obligations. The President / Dean participates in, and contributes to, the life and mission of the Canadian Baptists of Atlantic Canada. While committed to historic Baptist principles, the President / Dean values diversity and works effectively with a broad spectrum of multi-denominational and non- denominational partners in advancing the work of the College. As Dean of the Faculty of Theology for Acadia University, the President is an academic leader, engaged with the academy, and committed to ensuring academic rigour in ADC faculty and students, as well as works collaboratively with the President and Vice-Chancellor of the University -

Application for Name Change

3377 Bayview Avenue TEL: 416.226.6620 Toronto, ON www.tyndale.ca M2M 3S4 Application for Name Change Executive Summary Tyndale University College & Seminary was established through an act of legislation in 2003 as a natural progression of over 125 years of history of providing post-secondary education in the province of Ontario. The change in legislation afforded Tyndale the opportunity to provide undergraduate university quality education through a series of Bachelor of Arts (BA) degrees to complement a thriving graduate school (Tyndale Seminary) whose recognition as a tier one graduate school for theological education and counselling psychotherapy was known throughout North America. The undergraduate programs have complemented the graduate school by providing a quality undergraduate university opportunity. Undergraduate student learning outcomes are similar to any BA program in the province; however, the nomenclature University College has proven difficult to explain and market. Tyndale is one of only two independent University Colleges in the province not federated/affiliated with any institutional member of the Council of Ontario Universities. Students and families who are making post-secondary decisions are, therefore, unfamiliar with the term and interpret it to mean something less than a university degree. In jurisdictions outside of Ontario, most of the provinces have moved away from the nomenclature of University College preferring that all of their undergraduate universities are known as Universities. This has created a hardship in our ability to attract students both from within and outside of the province. We strongly believe that a private faith based university in the city of Toronto can attract and grow its enrolment by attracting students from other Canadian jurisdictions while at the same time keeping students in Ontario who are considering our competitors. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Rev. Lee Martin Mcdonald, Ph.D

CURRICULUM VITAE July, 2013 Rev. Lee Martin McDonald, Ph.D. President and Professor of New Testament Studies, Acadia Divinity College (1999-2007) and Dean of the Faculty of Theology, Acadia University, Wolfville, Nova Scotia (1999-2007); Past President, Institute for Biblical Research, (2006-2012); Visiting Professor, Princeton Theological Seminary (June 2007- June 2008) Adjunct Professor of Biblical Studies, Fuller Theological Seminary (1985-1999 and 2008-2010) Adjunct Professor of Biblical Studies, Arizona State University, Tempe, Arizona (2010 to present) EDUCATION B.A., Biola University, La Mirada, California, (Religion) B.D., Talbot Theological Seminary, La Mirada, California (Magna Cum Laude) Th.M., Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts, (Honors). Ph.D., University of Edinburgh, Scotland PERSONAL Married with four children, six grandchildren. Ordination in the American Baptist Churches of the USA, and recognized by the Canadian Baptist Ministries of Canada. CONTINUING EDUCATION University of Heidelberg, Germany, under direction of Günther Bornkamm, 1971-72. Cambridge University, England. 1971 and 1972 under direction of C. F. D. Moule at Clair College. Case Study Institute (Teaching Fellow), Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1976. Weston School of Theology, Cambridge, Massachusetts (Patristics), 1983-85. Harvard University, Cambridge, MA. (Patristic Latin and Theological German), 1980. Presidential Seminar, Cambridge University, Cambridge, England, July 2006. Visiting Scholar and Professor at Princeton Theological Seminary, 2007 and 2008. ACADEMIC AND PROFESSIONAL MEMBERSHIPS AND POSITIONS Institute for Biblical Research, Inc. member 1975-present. President 2006 to present Society of Biblical Literature, member, 1975 to present. Societas Novum Testamentum Studiorum, member 2005 to present. Association of Case Teaching, 1976 – 1996 Association of Theological Schools in Canada and the USA, member 1999 to 2007. -

Curriculum Vitae Roger E. Olson Present Position and Address

CURRICULUM VITAE ROGER E. OLSON PRESENT POSITION AND ADDRESS Professor of Theology, George W. Truett Theological Seminary, Baylor University (1999- present); P.O. Box 97126, Waco, TX 76798. BIOGRAPHY AND PERSONAL INFORMATION Born in Des Moines, Iowa February 2, 1952. Raised in Pastor's home. Graduated from High School in Sioux Falls, South Dakota in 1970. Married Becky Jeanne Sandahl in 1973. Two children: Sonja Kristen and Amanda Joy. Interested in geography and current events, amateur photography, bowling, gardening and gospel music. EDUCATION B.A. in Biblical and Theological Studies, Open Bible College, Des Moines, Iowa, 1974 (magna cum laude) M.A. in Religious Studies, North American Baptist Seminary, Sioux Falls, South Dakota, 1978 (magna cum laude) M.A. in Religious Studies, Rice University, Houston, Texas, 1982 ("With Honor") Ph.D. in Religious Studies, Rice University, Houston, Texas, 1984 Courses in German language and culture: University of Houston, Houston, Texas, 1980; Goethe Institute, Munich, West Germany, 1981; University of Munich, 1981 Graduate courses in Theology: SHALOM (Center for Continuing Theological Studies), Sioux Falls, South Dakota, 1975 and 1976; Bethel Theological Seminary, St. Paul, Minnesota, 1985 Research and studies at the Institut für Ökumene und Fundamentaltheologie of the Evangelische Fakultät of the University of Munich (Prof. Dr. Wolfhart Pannenberg, Chairman), Munich, West Germany, 1981-1982 SCHOLARSHIPS, FELLOWSHIPS, AND GRANTS Full Tuition Scholarships and Teaching Assistantships, Rice University, Houston, Texas, 1978-1981 University Fellowship for Overseas Study, Rice University, Houston, Texas, 1981-1982 Faculty Development Grant for research on nineteenth and twentieth century theology, 1988 Alumni Grant for research and development of companion volume of readings for book 1 Roger E. -

Preparing "Workers for the Harvest": Designing A

Preparing "Workers for the Harvest": Designing a Personalized Syllabus for Pre-Ministry Development to Facilitate the Transition from Calling to Effective Ministry in Convention of Atlantic Baptist Churches by Margo Lori MacDougall B.A. (Hon.), Carleton University, 1985 M.A., Winnipeg Theological Seminary, 1987 M.Div., Acadia Divinity College, 1995 Thesis-Project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Ministry Acadia Divinity College, Acadia University Spring Convocation 2008 © by Margo Lori MacDougall 2008 I, Margo Lori MacDougall, grant permission to the University Librarian at Acadia University to reproduce, loan, or distrubute copies of my thesis in microform, paper or electronic formats on a non-profit basis. I, however, retain the copyright in my thesis. Signature of Author Date This thesis by Margo Lori MacDougall was defended successfully in an oral examination on 24 March 2008. The examining committee for the thesis was: Dr. Andrew MacRae, Director/Chair Dr. Allison Trites, External Examiner Dr. Ida Armstrong-Whitehouse, External Examiner Dr. Carol Anne Janzen, Faculty Reader Dr. Bruce Fawcett, Supervisor Dr. Harry Gardner, President This thesis is accepted in its present form by Acadia Divinity College, the Faculty of Theology of Acadia University, as satisfying the thesis requirements for the Doctor of Ministry degree. CONTENTS List of Tables vi Abstract vii List of Abbreviations viii Acknowledgement and Dedication ix Chapter Introduction 1 1. Why Christians Prepare for Leadership in the Ministry: Biblical, Historical, and Theological Foundations 4 Hebrew Leadership in the Old Testament Brief History, Etymology, and Practices of the Old Testament Priest Brief History, Etymology, and Practices of the Old Testament Levite Brief History, Etymology, and Practices of the Old Testament Prophet Spiritual Leadership in the New Testament Brief History, Etymology, and Practices of the Ministry in the Gospels Brief History, Etymology, and Practices of the Ministry in the Acts and Epistles 2.