Argentinean and Chilean Wines in Sweden Before 1950

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wines of Chile

PREVIEWCOPY Wines of South America: Chile Version 1.0 by David Raezer and Jennifer Raezer © 2012 by Approach Guides (text, images, & illustrations, except those to which specific attribution is given) All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, without permission in writing from the publisher. Further, this book is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This book may not be resold or given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each recipient. Approach Guides and the Approach Guides logo are the property of Approach Guides LLC. Other marks are the prop- erty of their respective owners. Although every effort was made to ensure that the information was as accurate as possible, we accept no responsibility for any loss, damage, injury, or inconvenience sustained by anyone using this guidebook. Approach Guides New York, NY www.approachguides.com PREVIEWISBN: 978-1-936614-36-3COPY This Approach Guide was produced in collaboration with Wines of Chile. Contents Introduction Primary Grape Varieties Map of Winegrowing Regions NORTH Elqui Valley Limarí Valley CENTRAL Aconcagua Valley * Cachapoal Valley Casablanca Valley * Colchagua Valley * Curicó Valley Maipo Valley * Maule Valley San Antonio Valley * SOUTH PREVIEWCOPY Bío Bío Valley * Itata Valley Malleco Valley Vintages About Approach Guides Contact Free Updates and Enhancements More from Approach Guides More from Approach Guides Introduction Previewing this book? Please check out our enhanced preview, which offers a deeper look at this guidebook. The wines of South America continue to garner global recognition, fueled by ongoing quality im- provements and continued attractive price points. -

Nonlinear Hedonic Pricing: a Confirmatory Study of South African Wines

International Journal of Wine Research Dovepress open access to scientific and medical research Open Access Full Text Article ORIGINAL RESEARCH Nonlinear hedonic pricing: a confirmatory study of South African wines David A Priilaid1 Abstract: With a sample of South African red and white wines, this paper investigates the Paul van Rensburg2 relationship between price, value, and value for money. The analysis is derived from a suite of regression models using some 1358 wines drawn from the 2007 period, which, along with red 1School of Management Studies, 2Department of Finance and Tax, and white blends, includes eight cultivars. Using the five-star rating, each wine was rated both University of Cape Town, sighted and blind by respected South African publications. These two ratings were deployed in Republic of South Africa a stripped-down customer-facing hedonic price analysis that confirms (1) the unequal pricing of consecutive increments in star-styled wine quality assessments and (2) that the relationship between value and price can be better estimated by treating successive wine quality increments as dichotomous “dummy” variables. Through the deployment of nonlinear hedonic pricing, For personal use only. fertile areas for bargain hunting can thus be found at the top end of the price continuum as much as at the bottom, thereby assisting retailers and consumers in better identifying wines that offer value for money. Keywords: price, value, wine Introduction Within economics, “hedonics” is defined as the pleasure, utility, or efficacy derived through the consumption of a particular good or service; the hedonic model thereby proposes a market of assorted products with a range of associated price, quality, and characteristic differences and a diverse population of consumers, each with a varying propensity to pay for certain attribute assemblages. -

Wines by the Glass Champagne & Sparkling Chardonnay Sauvignon Blanc Pinot Grigio & Pinot Gris Interesting Whites Caberne

Wine Feature Mohua Sauvignon Blanc, Marlborough, 2015 Ripe and juicy tropical fruits, rich stone fruit and fresh cut lime combined with notes of fresh picked summer herbs. glass 12 bottle 47 champagne & sparkling cabernet sauvignon & blends Veuve Clicquot Ponsardin, Brut Reims NV 120 Caymus Vineyards Napa Valley 2013 150 Domaine Chandon, Blanc de Noirs Carneros NV 50 Alexander Valley Vineyards Alexander Valley 2013 55 Moët & Chandon, Imperial Épernay NV 105 Jordan Alexander Valley 2012 119 Moët & Chandon, Dom Pérignon Épernay 2003 275 Silver Oak Alexander Valley 2011 149 Santa Margherita, Prosecco Brut Italy NV 54 Caymus, Special Selection Napa Valley 2013 250 Taittinger Comtes de Champagne France 2000 395 Nickel & Nickel, Sullenger Vineyard Oakville 2013 165 Cakebread Cellars Napa Valley 2012 149 chardonnay William Hill Napa Valley 2012 80 Jordan Russian River Valley 2013 75 Estancia Meritage Paso Robles 2013 72 Sonoma-Cutrer Russian River Valley 2014 59 Red Diamond California 2012 31 Ferrari-Carano Alexander Valley 2014 70 Quintessa Rutherford 2011 205 Grgich Hills Napa Valley 2012 110 Opus One Napa Valley 2012 295 Lindeman’s Bin 65 Australia 2015 27 Hogue Cellars Columbia Valley 2014 28 Cakebread Cellars Napa Valley 2013 95 Louis M. Martini Napa Valley 2012 52 Far Niente Napa Valley 2014 120 J. Lohr Hilltop Vineyard Paso Robles 2013 70 Kistler ‘Les Noisetiers’ Sonoma County 2014 145 Cryptic Red California 2012 39 Stags’ Leap Winery Stags Leap District 2013 72 Louis Latour Meursault 2013 115 J. Lohr ‘Seven Oaks’ Paso Robles 2013 43 Louis Latour Puligny-Montrachet 2013 125 Murphy-Goode ‘Homefront Red’ Blend California 2012 39 Casa Lapostolle Casablanca Vineyard 2013 39 Concha Y Toro ‘Gran Reserva’ Chile 2013 43 Chateau Ste. -

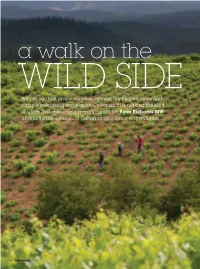

Peter Richards MW on Chile for Imbibe

a walk on the WILD SIDE With its oddball grape varieties, ancient dry-farmed vines and funky winemaking techniques, Chile’s south is making the kind of wines that restaurants are crying out for. Peter Richards MW abandons the comforts of Cabernet Sauvignon to investigate 64 imbibe.com Chile2.indd 64 4/23/2015 4:15:29 PM SOUTHERN CHILE MAIN & ABOVE: EXPLORING THE VINEYARDS OF ITATA. FAR RIGHT: HARVEST TIME AT GARCIA + SCHWADERER s Chile really worth the effort? It’s out via Carmenère, Pinot Noir and Syrah. host of other (often unidentifi ed) varieties a question – often expressed as a Yet still, the perception persists of a grew on granite soils amid rolling hills Iresigned reaction – that is fairly country that delivers solid, maybe ever- and a milder, more temperate climate widespread in the on-trade. Perhaps improving wines but which neither make than warmer areas to the north. it’s understandable, given how many the fi nest partners for food, nor have the The hills around the port city of brilliant wines from all over the globe capacity to get people excited – be they Concepción are considered Chile’s longest vie for attention in our bustling and sommeliers or diners. established vineyard, and it’s a sobering colourful marketplace, including tried This, of course, begs the question: thought that, given it was fi rst developed and tested favourites. what does get people excited when it in the mid- to late-16th century by Jesuit But it’s also based on a missionaries, this area has more conception of Chile as somewhat winemaking history than the predictable and limited in both great estates of the Médoc. -

1000 Best Wine Secrets Contains All the Information Novice and Experienced Wine Drinkers Need to Feel at Home Best in Any Restaurant, Home Or Vineyard

1000bestwine_fullcover 9/5/06 3:11 PM Page 1 1000 THE ESSENTIAL 1000 GUIDE FOR WINE LOVERS 10001000 Are you unsure about the appropriate way to taste wine at a restaurant? Or confused about which wine to order with best catfish? 1000 Best Wine Secrets contains all the information novice and experienced wine drinkers need to feel at home best in any restaurant, home or vineyard. wine An essential addition to any wine lover’s shelf! wine SECRETS INCLUDE: * Buying the perfect bottle of wine * Serving wine like a pro secrets * Wine tips from around the globe Become a Wine Connoisseur * Choosing the right bottle of wine for any occasion * Secrets to buying great wine secrets * Detecting faulty wine and sending it back * Insider secrets about * Understanding wine labels wines from around the world If you are tired of not know- * Serve and taste wine is a wine writer Carolyn Hammond ing the proper wine etiquette, like a pro and founder of the Wine Tribune. 1000 Best Wine Secrets is the She holds a diploma in Wine and * Pairing food and wine Spirits from the internationally rec- only book you will need to ognized Wine and Spirit Education become a wine connoisseur. Trust. As well as her expertise as a wine professional, Ms. Hammond is a seasoned journalist who has written for a number of major daily Cookbooks/ newspapers. She has contributed Bartending $12.95 U.S. UPC to Decanter, Decanter.com and $16.95 CAN Wine & Spirit International. hammond ISBN-13: 978-1-4022-0808-9 ISBN-10: 1-4022-0808-1 Carolyn EAN www.sourcebooks.com Hammond 1000WineFINAL_INT 8/24/06 2:21 PM Page i 1000 Best Wine Secrets 1000WineFINAL_INT 8/24/06 2:21 PM Page ii 1000WineFINAL_INT 8/24/06 2:21 PM Page iii 1000 Best Wine Secrets CAROLYN HAMMOND 1000WineFINAL_INT 8/24/06 2:21 PM Page iv Copyright © 2006 by Carolyn Hammond Cover and internal design © 2006 by Sourcebooks, Inc. -

First Virtual 2020 ACR Conference Program October 1-4, 2020

First Virtual 2020 ACR Conference Program October 1-4, 2020 Can Brands be Sarcastic Conference Registration - https://www.acrwebsite.org/go/ACR2020Register Conference Agenda Access - Whova 2020 ACR Conference Access Info.pdf Wednesday, September 30, 2020 Advancing Diversity, Equity, 10:00 am - 12:00 pm (EDT) and Inclusion in Consumer Research Thursday, October 1, 2020 Early Career Workshop 9:00 am - 10:00 am (EDT) 10:00 am - 11:00 am (EDT) 8:00 pm - 9:00 pm (EDT) 9:00 pm - 10:00 pm (EDT) JACR Special Issue Workshop- by invitation only 10:30 am - 1:30 pm (EDT) This was set up by JACR so it only appears on the website for information, there’s not a live link to it as it is by Invitation Only. ACR-Sheth Doctoral Symposium 12:00 pm - 3:00 pm (EDT) Virtual Opening Reception 7:00 pm New York (EDT) 7:00 pm Paris (Paris Time) 7:00 pm (Sydney time for Asia/Australia) Friday, October 2, 2020 The Keith Hunt Newcomers’ Meet and Greet 9:30 am - 10:00 am (EDT) Eileen Fischer - President’s Address 10:00 am - 10:30 am (EDT) Business Meeting/Awards Ceremony 10:30 am - 11:30 am (EDT) Knowledge Forums 12:00 pm - 1:15 pm (EDT) Virtual Happy Hour 7:00 pm New York (EDT) 7:00 pm Paris (Paris Time) 7:00 pm (Sydney time for Asia/Australia) Saturday, October 3, 2020 Knowledge Forums 9:30 am - 10:45 am (EDT) 11:00 am - 12:15 pm (EDT) Virtual Closing Night Reception 7:00 pm New York (EDT)) 7:00 pm Paris (Paris Time) 7:00 pm (Sydney time for Asia/Australia) 1 First Virtual 2020 ACR Conference Program October 1-4, 2020 Friday & Saturday, October 2 & 3, 2020 The following -

Talking About Wine 11

11 Talking about wine 1 Put the conversation in the correct order. a 1 waiter: Would you like to order some wine with your meal? b woman: Yes, a glass of Pinot Grigio, please. c waiter: The Chardonnay is sweeter than the Sauvignon Blanc. d man: We’d like two glasses of red to go with our main course. Which is smoother, the Chianti or the Bordeaux? e waiter: Well, they are both excellent wines. I recommend the Bordeaux. It’s more full-bodied than the Chianti and it isn’t as expensive. f man: Yes, please. Which is sweeter, the Chardonnay or the Sauvignon Blanc? g man: Right. I’ll have a glass of Chardonnay, then. Sarah, you prefer something drier, don’t you? h man: OK then, let’s have the Bordeaux. i waiter: Certainly, madam. And what would you like with your main course? j woman: Yes, a bottle of sparkling water, please. k waiter: Thank you, sir. Would you like some mineral water? l 12 waiter: OK, so that’s a glass of Chardonnay, a glass of Pinot Grigio, two glasses of Bordeaux and a bottle of sparkling mineral water. 2 Find the mistakes in each sentence and correct them. 1 The Chilean Merlot is not more as expensive as the French. 2 The Riesling is sweet than the Chardonnay. 3 The Pinot Grigio is drier as the Sauvignon Blanc. 4 Chilean wine is most popular than Spanish. 5 A Chianti is no as full-bodied as a good Bordeaux. 6 Champagne is more famous the sherry. -

WINE LIST Gl / Btl HOUSE Canyon Road / Vista Point - Chardonnay, Pinot Grigio, Pinot Noir, Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot 6 / 20

WINE LIST gl / btl HOUSE Canyon Road / Vista Point - Chardonnay, Pinot Grigio, Pinot Noir, Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot 6 / 20 BUBBLES gl / btl ROSE gl / btl Lamarca, Prosecco, split, Italy 12 La Vieille Ferme, Rose, Rhone Valley, France 8 / 30 J. Roget, Brut, American Champagne, New York 6 / 20 Chloe, Rose, Central Coast, California 9 / 35 Campo Viejo, Cava Brut Rose, Sparkling Wine, Spain 8 / 30 Del Rio Estate, Grenache Rose, Rogue Valley, Oregon 38 G.H. Mumm, Grand Cordon Brut, Champagne, France 75 Daou, Rose, Paso Robles, California 45 WHITES gl / btl REDS gl / btl William Hill, Chardonnay, Central Coast, California 9 / 35 Cannonball, Cabernet Sauvignon, Healdsburg, California 9 / 35 Acrobat, Chardonnay, Eugene, Oregon 10 / 38 Freak Show, Cabernet Sauvignon, Graton, California 12 / 45 Buehler, Chardonnay, Russian River Valley, California 12 / 45 Del Rio, Cabernet Sauvignon, Rogue Valley, Oregon 50 Annabella, Chardonnay, Napa Valley, California 35 Substance, Cabernet Sauvignon, Benton City, Washington 60 Cave de Lugny, Chardonnay, Macon-Lugny, France 40 Kenwood, Cabernet Sauvignon, Sonoma Mountain, California 75 Walt, Chardonnay, Sonoma Coast, California 75 Arrowood, Cabernet Sauvignon, Knights Valley, Sonoma, California 90 Grounded, Sauvignon Blanc, Hopland, California 9 / 35 Stemmari, Pinot Noir, sustainable, Sicily, Italy 9 / 35 Oyster Bay, Sauvignon Blanc, Marlborough, New Zealand 10 / 38 Meiomi, Pinot Noir, tri-county Coastal, California 12 / 45 Los Cardos, Sauvignon Blanc, Mendoza, Argentina 30 Montinore Estate, Pinot Noir, Willamette -

Italian Wine Spanish Wine Chilean Wine

I T A L I A N W I N E Tere Nere Brunello -750ml Ilpumo Primitivo -750ml Tere Di Bio Barbaresco -750ml Casata Parini Montepulciano -750 ml Neirano Barolo -750ml Gorotti Sangiovese Merlot - 750ml Argano Toscana -750ml Primaverina Rosso -750ml Borgo Bella Toscana -750ml Nine 17 Sangiovese -750ml Barone Montalto -750ml Barone Ricasoli Chianti - 750ml Brico Al Sole Montepulciano -750ml Sermann Pinot Grigio -750ml Castorani Montepulciano -750ml Oko Organic Pinot Grigio -750 ml Terranosta Primitivo -750ml S P A N I S H W I N E La Maltida Rioja -750ml Castilo De Fuente Monastrell -750ml Lan Rioja -750ml Broken Ass Red Blend -750ml Sin Complejos Rioja -750ml Gran Vinaio -750ml Terra Unica Tempranillo -750ml Honoro Vera Granacha -750ml Miyone Granacha -750ml Xenys Monastrell -750ml Taja Monastrell -750ml Altos Rosal -750ml Campo Viejo Rioja -750ml Foresta Sauvignon Blanc -750ml C H I L E A N W I N E Toro De Piedra Cabernet Sauvignon 2015 -750ml Casa Del Toro Pinot Noir 2018 -1750 ml & 750ml Casa Del Toro Cabernet Sauvignon 1750 ml & 750ml Lanzur Merlot 2017 -750ml Lanzur Shiraz 2015 -750ml Sassy Chardonnay 2016 -750ml Sassy Merlot 2016 -750ml Layla Merlot 2015 -750ml Don Tony Perez Chardonnay -750ml Layla Chardonnay -750ml Marchigue Gran Reserva -750ml Puerto Viejo Merlot - 750ml F R E N C H W I N E Chateau Bellevue Bordeaux 2018 - 750ml Chateau De Lavagnac Bordeaux 2016 -750ml Cotes Du Rhone Loiseau 2017 -750ml Macon Vilages Mommessin 2013 -750ml Chateauneuf-Du- Pape E. Chambellan 2016 -750ml Guigal Hermitage -750ml Beaujolais- Villages Vieilles Vignes 2019 -750ml Magali Mathray Fleurie 2015 -750ml Cotes -Du _ Rhone Bonpass -750ml Bourgogne Grand Ordinare 2014 -750 ml Beaujolais - Villages Chameroy L. -

Sonoma County Champagne Och Andra Fyrverkerier

Sonoma County Champagne och andra fyrverkerier Port – världsklass till reapris Taylor’s Nr 8 • 2011 Organ för Munskänkarna Årgång 54 • 2011 • 8 Vinprovning Ansvarig utgivare Ylva Sundkvist – för både samvaro och tävling Redaktör VINTERN NÄRMAR SIG i rask takt och jag är nu inne på mitt femte år i styrelsen. Otroligt vad tiden går fort Munskänken/VinJournalen Ulf Jansson, Oxenstiernsgatan 23, när man håller på med nåt som är kul och spännande. Via Munskänkarna har jag haft förmånen att få 115 27 Stockholm träffa många trevliga och engagerade människor. Vinprovning är en hobby som både stimulerar intellektet Tel 08-667 21 42 och skapar trevlig stämning. Det kan också vara roligt att tävla. Att gissa druva hemma i soffan eller att se vem som prickar flest viner i kompisgänget är ju sånt som vi alla tycker är roligt ibland. Nu senast fick jag Annonser chansen att träffa likasinnade från många länder vid vinprovnings-EM i Priorat. Munskänkarna i Sverige Urban Hedborg är en världsunik förening där vi lyckats samla många medlemmar på nationell basis och man ser på oss Tel 08-732 48 50 med stor respekt. Nästa år får vi chansen att visa framfötterna på hemmaplan, både som tävlande och som e-post: [email protected] medarrangörer. Våra vänner i Finland har då också aviserat att ställa upp som ny nation. Att tävla i vinprov- Produktion och ning är alltid mycket spännande och jag tror att vi kan locka både publik och medier till detta arrangemang. Grafisk form Exaktamedia, Malmö NÅGOT SOM DOCK ÄR oroande är att flera av våra sektioner har börjat få problem med lokala handläggare monika.fogelberg@ kring serveringstillstånd. -

HLSR Rodeouncorked 2014 International Wine Competition Results

HLSR RodeoUncorked 2014 International Wine Competition Results AWARD Wine Name Class Medal Region Grand Champion Best of Show, Marchesi Antinori Srl Guado al Tasso, Bolgheri DOC Superiore, 2009 Old World Bordeaux-Blend Red Double-Gold Italy Class Champion Reserve Grand Champion, Class Sonoma-Cutrer Vineyards Estate Bottled Pinot Noir, Russian River New World Pinot Noir ($23-$35) Double-Gold U.S. Champion Valley, 2010 Top Texas, Class Champion, Bending Branch Winery Estate Grown Tannat, Texas Hill Country, 2011 Tannat Double-Gold Texas Texas Class Champion Top Chilean, Class Champion, Chilean Cabernet Sauvignon ($16 and La Playa Vineyards Axel Cabernet Sauvignon, Colchagua Valley, 2011 Double-Gold Chile Chile Class Champion higher) Top Red, Class Champion Fess Parker Winery The Big Easy, Santa Barbara County, 2011 Other Rhone-Style Varietals/Blends Double-Gold U.S. Top White, Class Champion Sheldrake Point Riesling, Finger Lakes, 2011 Riesling - Semi-Dry Double-Gold U.S. Top Sparkling, Class Champion Sophora Sparkling Rose, New Zealand, NV Sparkling Rose Double-Gold New Zealand Top Sweet, Class Champion Sheldrake Point Riesling Ice Wine, Finger Lakes, 2010 Riesling-Sweet Double-Gold U.S. Top Value, Class Champion Vigilance Red Blend " Cimarron", Red Hills Lake County, 2011 Cab-Syrah/Syrah-Cab Blends Double-Gold U.S. Top Winery Michael David Winery Top Wine Outfit Trinchero Family Estates Top Chilean Wine Outfit Concha Y Toro AWARD Wine Name Class Medal Region 10 Span Chardonnay, Central Coast, California, 2012 Chardonnay wooded ($10 -$12) Silver U.S. 10 Span Pinot Gris, Monterey, California, 2012 Pinot Gris/Pinot Grigio ($11-$15) Silver U.S. -

Duval's Retail Wines

Duval’s Retail Wines Exceptional Value Whites Veuve du Vernay – Split - Brut Sparkling – France 6 Valdo – Split - Brut Prosecco – Italy 5 Beringer White Zinfandel – CA 8 Vie Vité Rosé – Côtes de Provence, France 19 Essence Riesling – Mosel, Germany 17 Moonlight White Blend – Tuscany, Italy 17 Benvolio Pinot Grigio – Friuli, Italy 10 La Crema Pinot Gris – Monterey, CA 10 Justin Sauvignon Blanc – Paso Robles, CA 14 Dog Point Vineyard Sauvignon Blanc – Marlborough, New Zealand 17 Parducci Chardonnay – Mendocino, CA 11 Cambria “Benchbreak Vineyard” Chardonnay – Santa Maria Valley, CA 13.5 Trefethen Chardonnay – Oak Knoll, Napa Valley, CA 19 Exceptional Value Reds Steelhead Pinot Noir – Sonoma, CA 13 Acrobat Pinot Noir – Oregon 18 Meiomi Pinot Noir – Sonoma, CA 16.5 Collina Chianti – Tuscany, Italy 10 Santa Ema Merlot – Chile 17.5 Michel Torino “Colección” Malbec – Calchaquí Valley, Argentina 17 Brazin “Old Vine” Zinfandel – Lodi, CA 13.5 Trapiche “Broquel” Malbec – Mendoza, Argentina 15 Wente S. Hill Cabernet Sauvignon – Livermore Valley, CA 14 One Hope Cabernet Sauvignon - CA 13 Uppercut Cabernet Sauvignon – California 19 Robert Mondavi Cabernet Sauvignon – Napa Valley, CA 23.5 Champagne & Sparkling Wines Valdo Brut DOC Prosecco – Valdobiaddene, Italy 16 Segura Viudas Brut Reserva Cava – Spain 14 Roederer Estate Brut Rosé Sparkling – Anderson Valley, CA 33 Argyle Brut Sparkling – Willamette Valley, Oregon 23 Veuve Cliquot “Yellow Label” Brut – Champagne, France 76.5 Laurent-Perrier Brut Cuvée Rosé – Champagne, France 63 Light To Medium-Bodied