Downloaded From

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spatial Dimensions of Conflict-Induced Internally Displaced Population in the Puttalam District of Sri Lanka from 1980 to 2012 Deepthi Lekani Waidyasekera

University of North Dakota UND Scholarly Commons Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Senior Projects 12-1-2012 Spatial Dimensions of Conflict-Induced Internally Displaced Population in the Puttalam District of Sri Lanka from 1980 to 2012 Deepthi Lekani Waidyasekera Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/theses Recommended Citation Waidyasekera, Deepthi Lekani, "Spatial Dimensions of Conflict-Induced Internally Displaced Population in the Puttalam District of Sri Lanka from 1980 to 2012" (2012). Theses and Dissertations. 668. https://commons.und.edu/theses/668 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, and Senior Projects at UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SPATIAL DIMENSIONS OF CONFLICT-INDUCED INTERNALLY DISPLACED POPULATION IN THE PUTTALAM DISTRICT OF SRI LANKA FROM 1980 TO 2012 by Deepthi Lekani Waidyasekera Bachelor of Arts, University of Sri Jayawardanapura,, Sri Lanka, 1986 Master of Science, University of Moratuwa, Sri Lanka, 2001 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of North Dakota In partial fulfilment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Arts Grand Forks, North Dakota December 2012 Copyright 2012 Deepthi Lekani Waidyasekera ii PERMISSION Title Spatial Dimensions of Conflict-Induced Internally Displaced Population in the Puttalam District of Sri Lanka from 1980 to 2012 Department Geography Degree Master of Arts In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a graduate degree from the University of North Dakota, I agree that the library of the University shall make it freely available for inspection. -

World Bank Document

Document of The World Bank FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Public Disclosure Authorized Report No: 3 8 147 - LK PROJECT APPRAISAL DOCUMENT ON A Public Disclosure Authorized PROPOSED CREDIT IN THE AMOUNT OF SDR 21.7 MILLION (US$32 MILLION EQUIVALENT) TO THE DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA FOR A PUTTALAM HOUSING PROJECT Public Disclosure Authorized JANUARY 24,2007 Sustainable Development South Asia Region Public Disclosure Authorized This document has a restricted distribution and may be used by recipients only in the performance of their official duties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosed without World Bank authorization. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective December 13,2006) Currency Unit = Sri Lankan Rupee 108 Rupees (Rs.) = US$1 US$1.50609 = SDR 1 FISCAL YEAR January 1 - December 31 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ADB Asian Development Bank LTF Land Task Force AG Auditor General LTTE Liberation Tigers ofTamil Eelam CAS Country Assistance Strategy NCB National Competitive Bidding CEB Ceylon Electricity Board NGO Non Governmental Organization CFAA Country Financial Accountability Assessment NEIAP North East Irrigated Agriculture Project CQS Selection Cased on Consultants Qualifications NEHRP North East Housing Reconstruction Program CSIA Continuous Social Impact Assessment NPA National Procurement Agency CSP Camp Social Profile NPV Not Present Value CWSSP Community Water Supply and Sanitation NWPEA North Western Provincial Environmental Act Project DMC District Monitoring Committees NWPRD NorthWest Provincial Roads Department -

Fisheries and Environmental Profile of Chilaw Estuary

REGIONAL FISHERIES LIVELIHOODS PROGRAMME FOR SOUTH AND SOUTHEAST ASIA (RFLP) --------------------------------------------------------- Fisheries and environmental profile of Chilaw lagoon: a literature review (Activity 1.3.1 Prepare fisheries and environmental profile of Chilaw lagoon using secondary data and survey reports) For the Regional Fisheries Livelihoods Programme for South and Southeast Asia Prepared by Leslie Joseph Co-management consultant June 2011 DISCLAIMER AND COPYRIGHT TEXT "This publication has been made with the financial support of the Spanish Agency of International Cooperation for Development (AECID) through an FAO trust-fund project, the Regional Fisheries Livelihoods Programme (RFLP) for South and Southeast Asia. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the opinion of FAO, AECID, or RFLP.” All rights reserved. Reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product for educational and other non-commercial purposes are authorized without any prior written permission from the copyright holders provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of material in this information product for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without written permission of the copyright holders. Applications for such permission should be addressed to: Chief Electronic Publishing Policy and Support Branch Communication Division FAO Viale delle Terme di Caracalla, 00153 Rome, Italy or by e-mail to: [email protected] © FAO 2011 Bibliographic reference For bibliographic purposes, please -

Performance Report 2014 (A Brief Performance Report of the Key Sections and the Provincial Offices Belong to the Department of Archaeology)

Performance Report 2014 (A brief performance report of the key sections and the provincial offices belong to The Department of Archaeology) Project Monitoring & Evaluation Division (Planning Division) Department of Archaeology Colombo - 07 Table of contents Page number Department of Archaeology (Vision, Mission, Objectives) 157 - 160 Exploration and Documentation Division 161 - 166 Excavation Division 167 - 171 Museum Services Division 172 - 174 Architectural Conservation Division 175 - 185 Chemical Preservation Division 186 - 190 Epigraphy and Numismatics Division 191 - 193 Maintenance Division 194 - 204 Promotional Division 205 - 207 Accounts Division 208 - 209 Administration Division 210 - 214 Project Monitoring & Evaluation Division 215 - 219 Legal Division 220 - 229 Performance Report - 2014 157 Department of Archaeology Vision The vision of the Department of Archaeology of Sri Lanka is to promote proper management of Sri Lanka‟s archeological heritage. Mission The mission of the Department of Archaeology of Sri Lanka is to function as Sri Lanka‟s apex institution and chief regulatory body for the management of its archaeological heritage. Objectives In order to fulfill its mission, the objectives of the Department of Archaeology of Sri Lanka are; 1) Development of resources (i.) Human (ii.) Institutional 2) Protection of the total archaeological heritage of Sri Lanka 3) Inventorisation of the archaeological heritage of Sri Lanka (i.) Archaeological sites and Monuments (ii.) Movable antiquities 4) Enhancement of public awareness -

Download PDF 638 KB

Working Paper 58 Developing Effective Institutions for Water Resources Management : A Case Study in the Deduru Oya Basin, Sri Lanka P. G. Somaratne K. Jinapala L. R. Perera B. R. Ariyaratne, D. J. Bandaragoda and Ian Makin International Water Management Institute i IWMI receives its principal funding from 58 governments, private foundations, and international and regional organizations known as the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR). Support is also given by the Governments of Ghana, Pakistan, South Africa, Sri Lanka and Thailand. The authors: P.G. Somaratne, L. R. Perera, and B. R. Ariyaratne are Senior Research Officers; K. Jinapala is a Research Associate; D. J. Bandaragoda is a Principal Researcher, and Ian Makin is the Regional Director, Southeast Asia, all of the International Water Management Institute. Somaratne, P. G.; Jinapala, K.; Perera, L. R.; Ariyaratne, B. R.; Bandaragaoda, D. J.; Makin, I. 2003. Developing effective institutions for water resources management: A case study in the Deduru Oya Basin, Sri Lanka. Colombo, Sri Lanka: International Water Management Institute. / river basins / water resource management / irrigation systems / groundwater / water resources development / farming / agricultural development / rivers / fish farming / irrigation programs / poverty / irrigated farming / water shortage / pumps / ecology / reservoirs / water distribution / institutions / environment / natural resources / water supply / drought / land use / water scarcity / cropping systems / agricultural production -

SFG1866 Public Disclosure Authorized

JAELA TO PUTTALAM SECTION i SFG1866 Public Disclosure Authorized Social Impact Assessment For TRANSPORT CONNECTIVITY AND ASSET MANAGEMENT PROJECT Public Disclosure Authorized JaEla to Puttalam Section of Peliyagoda - Puttalam Road (A03) Public Disclosure Authorized Road Development Authority Public Disclosure Authorized MINISTRY OF HIGHER EDUCATION AND HIGHWAYS 2016 Resources Development Consultants (Pvt) Ltd. JAELA TO PUTTALAM SECTION ii TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................................................................................ ii TABLE OF FIGURES ............................................................................................................. v TABLES .................................................................................................................................... v ACRONYMS .......................................................................................................................... vii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................................... 1 CHAPTER 01: PROJECT BACKGROUND ........................................................................ 3 1.1 The Project ....................................................................................................................... 3 1.2 Description of the project ................................................................................................. 3 CHAPTER 02: OBJECTIVES AND METHODOLOGY................................................... -

Lanka Government Network 2.0

Lanka Government Network 2.0 Bandwidth Utilization Report Report for PSC – June 19th 2018 May April March Criteria Criteria 3 BW BW Site Value Criteria 2 Site Name 1 (Max- (BW Allocated Group (Rs.)**** Avg Max Avg Max Avg Max (Avg-C)** (Mbps) (Mbps) (Mbps) (Mbps) (Mbps) (Mbps) C)* Upgrade)*** Addalachchenai Divisional Secretariat 2 Mbps E 83,650.95 0.43 1.98 0.34 1.56 0.43 1.97 N/A N/A No Agalawatta Divisional Secretariat 2 Mbps E 83,650.95 0.59 1.99 0.34 1.99 0.28 1.92 N/A N/A No Agunukolapalassa Prison 2 Mbps E - 0.05 0.16 0.04 0.06 0.05 0.11 N/A N/A No Akkaraipattu Divisional Secretariat 2 Mbps E 78,460.95 0.13 1.82 0.04 0.19 0.05 0.45 N/A N/A No Akkaraipattu Zonal Education Office 2 Mbps E 81,860.95 0.08 1.05 0.05 0.14 0.05 0.20 N/A N/A No Akurana Divisional Secretariat 2 Mbps E 87,230.95 0.40 1.69 0.33 1.97 0.31 1.85 N/A N/A No Akuressa Divisional Secretariat 2 Mbps E 88,840.95 0.99 1.99 0.46 1.99 0.89 1.99 N/A N/A No Akuressa Pradeshiya Sabha 2 Mbps E 78,460.95 0.14 1.22 0.07 0.39 0.07 0.15 N/A N/A No Alawwa Divisional Secretariat 2 Mbps E 78,280.95 0.30 1.56 0.31 1.83 0.20 1.73 N/A N/A No Alayadivembu Divisional Secretariat 2 Mbps E 78,460.95 0.62 1.95 0.48 1.74 0.49 1.74 N/A N/A No Ambagamuwa Koralaya Divisional Secretariat 2 Mbps E 87,230.95 0.19 1.16 0.07 0.32 0.04 0.55 N/A N/A No Ambalangoda Divisional Secretariat 2 Mbps E 92,600.95 0.31 1.91 0.36 1.98 0.19 1.46 N/A N/A No Ambalangoda Zonal Education Office 2 Mbps E 78,280.95 0.22 1.81 0.09 1.17 0.23 1.93 N/A N/A No Ambangangakorale Divisional Secretariat 2 Mbps E 81,860.95 -

The Case of Sri Lanka A

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Intra-Ethnic Electoral Violence in War-Torn, Divided Societies: The Case of Sri Lanka A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science by Seema Kiran Shah 2012 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Intra-Ethnic Electoral Violence in War-Torn, Divided Societies: The Case of Sri Lanka by Seema Kiran Shah Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science University of California, Los Angeles, 2012 Professor Edmond Keller, Chair What form does electoral violence take in war-torn divided societies, and what explains the variation in this type of violence? Using statistical and historical analyses, this study examines patterns of election-related violence in the war-torn, ethnically divided context of Sri Lanka. This study shows that electoral violence in Sri Lanka is more often the result of inter- party and intra-ethnic competition than it is the result of inter-ethnic rivalries. Since most Sri Lankan districts are ethnically homogeneous and because the Sinhalese constitute the vast majority of the population, most electoral competition occurs between rival Sinhalese parties. Specifically, this dissertation demonstrates the significance of inter-party competition within one ethnic group by showing that there was generally more violence in areas where the vote differences between the top two contenders were smallest, even when both were from the same ethnic group. This holds when comparing violence with the vote difference from the previous ii election cycle as well. When vote differences were small in the previous election, there was more violence in the following election in that district. -

12 Manogaran.Pdf

Ethnic Conflict and Reconciliation in Sri Lanka National Capilal District Boundarl3S * Province Boundaries Q 10 20 30 010;1)304050 Sri Lanka • Ethnic Conflict and Reconciliation in Sri Lanka CHELVADURAIMANOGARAN MW~1 UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII PRESS • HONOLULU - © 1987 University ofHawaii Press All Rights Reserved Manufactured in the United States ofAmerica Library ofCongress Cataloging-in-Publication-Data Manogaran, Chelvadurai, 1935- Ethnic conflict and reconciliation in Sri Lanka. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Sri Lanka-Politics and government. 2. Sri Lanka -Ethnic relations. 3. Tamils-Sri Lanka-Politics and government. I. Title. DS489.8.M36 1987 954.9'303 87-16247 ISBN 0-8248-1116-X • The prosperity ofa nation does not descend from the sky. Nor does it emerge from its own accord from the earth. It depends upon the conduct ofthe people that constitute the nation. We must recognize that the country does not mean just the lifeless soil around us. The country consists ofa conglomeration ofpeople and it is what they make ofit. To rectify the world and put it on proper path, we have to first rec tify ourselves and our conduct.... At the present time, when we see all over the country confusion, fear and anxiety, each one in every home must con ., tribute his share ofcool, calm love to suppress the anger and fury. No governmental authority can sup press it as effectively and as quickly as you can by love and brotherliness. SATHYA SAl BABA - • Contents List ofTables IX List ofFigures Xl Preface X111 Introduction 1 CHAPTER I Sinhalese-Tamil -

Puttalam Lagoon System an Environmental and Fisheries Profile

REGIONAL FISHERIES LIVELIHOODS PROGRAMME FOR SOUTH AND SOUTHEAST ASIA (RFLP) --------------------------------------------------------- An Environmental and Fisheries Profile of the Puttalam Lagoon System (Activity 1.4.1 : Consolidate and finalize reports on physio-chemical, geo-morphological, socio-economic, fisheries, environmental and land use associated with the Puttalam lagoon ecosystem) For the Regional Fisheries Livelihoods Programme for South and Southeast Asia Prepared by Sriyanie Miththapala (compiler) IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature, Sri Lanka Country Office October 2011 REGIONAL FISHERIES LIVELIHOODS PROGRAMME FOR SOUTH AND SOUTHEAST ASIA (RFLP) – SRI LANKA An Environmental and Fisheries Profile of the Puttalam Lagoon System (Activity 1.4.1- Consolidate and finalize reports on physio-chemical, geo-morphological, socio-economic, fisheries, environment and land use associated with Puttalam lagoon ecosystem) For the Regional Fisheries Livelihoods Programme for South and Southeast Asia Prepared by Sriyanie Miththapala (compiler) IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature, Sri Lanka Country Office October 2011 i Disclaimer and copyright text This publication has been made with the financial support of the Spanish Agency of International Cooperation for Development (AECID) through an FAO trust-fund project, the Regional Fisheries Livelihoods Programme (RFLP) for South and Southeast Asia. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the opinion of FAO, AECID, or RFLP. All rights reserved. Reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product for educational and other non-commercial purposes are authorized without any prior written permission from the copyright holders provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of material in this information product for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without written permission of the copyright holders. -

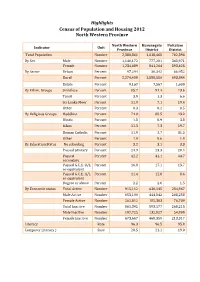

Sabaragamuwa Province Final Data

Highlights Census of Population and Housing 2012 North Western Province North Western Kurunegala Puttalam Indicator Unit Province District District Total Population Number 2,380,861 1,618,465 762,396 By Sex Male Number 1,146,172 777,201 368,971 Female Number 1,234,689 841,264 393,425 By Sector Urban Percent 97,294 30,342 66,952 Rural Percent 2,274,400 1,580,556 693,844 Estate Percent 9,167 7,567 1,600 By Ethnic Groups Sinhalese Percent 85.7 91.4 73.6 Tamil Percent 3.0 1.3 6.6 Sri Lanka Moor Percent 11.0 7.1 19.4 Other Percent 0.3 0.2 0.5 By Religious Groups Buddhist Percent 74.0 88.5 43.2 Hindu Percent 1.8 0.9 3.8 Islam Percent 11.3 7.3 19.7 Roman Catholic Percent 11.9 2.7 31.5 Other Percent 1.0 0.6 1.8 By Education Status No schooling Percent 3.2 3.1 3.3 Passed primary Percent 24.9 23.3 28.4 Passed Percent 42.2 41.1 44.7 secondary Passed G.C.E. O/L Percent 16.0 17.1 13.7 or equivalent Passed G.C.E. A/L Percent 11.4 12.8 8.4 or equivalent Degree or above Percent 2.2 2.6 1.5 By Economic status Total Active Number 915,112 630,145 284,967 Male Active Number 653,100 444,842 208,258 Female Active Number 262,012 185,303 76,709 Total Inactive Number 861,392 593,177 268,215 Male Inactive Number 187,725 132,827 54,898 Female Inactive Number 673,667 460,350 213,317 Literacy Rate 96.3 96.5 95.8 Computer Literacy ) Rate 20.5 21.1 19.0 Census of Population and Housing 2012 North Western Province 1.0 Introduction The Department of Census and Statistics provided through softcopies in CD’s. -

Map of Sri Lanka

MINISTRY OF HEALTH, NUTRITION & WELFARE, THE DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA (MOH) JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY (JICA) MASTER PLAN STUDY FOR STRENGTHENING HEALTH SYSTEM IN THE DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA SUPPORTING DOCUMENT III MAPS HEALTHY & SHINING ISLAND IN THE 21ST CENTURY FINAL REPORT NOVEMBER 2003 PACIFIC CONSULTANTS INTERNATIONAL The following foreign exchange rate is applied in the study: US$ 1.00 = 95 Sri Lanka Rupees (as of November 2003) November 2003 Mr. Kazuhisa MATSUOKA Vice President Japan International Cooperation Agency Tokyo, Japan Message from Vice President, Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) Letter of Transmittal Dear Sir, We are pleased to formally submit herewith the Final Report of “The Master Plan Study In response to a request from the Government of the Democratic Socialist Republic of for Strengthening Health System in the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka.” Sri Lanka, the Government of Japan decided to provide technical cooperation for This report compiles the results of the Study which was conducted from March 2002 establishing of a health master plan which will be effective for the next decade for the through November 2003 by the Study Team organized by Pacific Consultants improvement of the health system in Sri Lanka. JICA selected and dispatched the International under the contract with JICA. study team headed by Dr. Katsuhide Nagayama of Pacific Consultants International to The report compiles the Sri Lanka Health Master Plan covering both reform and Sri Lanka between March 2002 and November 2003. development of the health sector in Sri Lanka. The plan consists of 1) vision, goals and objectives; 2) overall basic strategies; 3) frameworks for health sector reform and I am pleased that the Health Master Plan, presented herewith by Ministry of Health, development; and 4) priority programmes.