Issue 68, Spring 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018

The Journal of Dress History Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018 Front Cover Image: Textile Detail of an Evening Dress, circa 1950s, Maker Unknown, Middlesex University Fashion Collection, London, England, F2021AB. The Middlesex University Fashion Collection comprises approximately 450 garments for women and men, textiles, accessories including hats, shoes, gloves, and more, plus hundreds of haberdashery items including buttons and trimmings, from the nineteenth century to the present day. Browse the Middlesex University Fashion Collection at https://tinyurl.com/middlesex-fashion. The Journal of Dress History Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018 Editor–in–Chief Jennifer Daley Editor Scott Hughes Myerly Proofreader Georgina Chappell Published by The Association of Dress Historians [email protected] www.dresshistorians.org The Journal of Dress History Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018 [email protected] www.dresshistorians.org Copyright © 2018 The Association of Dress Historians ISSN 2515–0995 Online Computer Library Centre (OCLC) accession #988749854 The Journal of Dress History is the academic publication of The Association of Dress Historians through which scholars can articulate original research in a constructive, interdisciplinary, and peer reviewed environment. The Association of Dress Historians supports and promotes the advancement of public knowledge and education in the history of dress and textiles. The Association of Dress Historians (ADH) is Registered Charity #1014876 of The Charity Commission for England and Wales. The Journal of Dress History is copyrighted by the publisher, The Association of Dress Historians, while each published author within the journal holds the copyright to their individual article. The Journal of Dress History is circulated solely for educational purposes, completely free of charge, and not for sale or profit. -

Kulturminnegrunnlag

KULTURMINNEGRUNNLAG for Forvaltningsplan for Byfjellene Sør Smøråsfjellet, Stendafjellet og Fanafjellet Byantikvaren 2006 Byrådsavdeling for Byutvikling Bergen kommune Kulturminnegrunnlag for Byfjellene Sør 2006 FORORD For forvaltningsplan for Byfjellene Sør Smøråsfjellet, Stendafjellet og Fanafjellet Det foreliggende kulturminnegrunnlaget er en del av Byantikvarens arbeid med å kartfeste og sikre informasjon og kunnskap om det historiske kulturlandskapet i Bergen kommune. Kulturminnegrunnlaget er utarbeidet i forbindelse med forvaltningsplan for Byfjellene, og er ment å gi en sammenfatning av kulturminneverdiene i området. Kulturminnegrunnlagene ser generelt på hovedstrukturene i et område, og fokuserer i mindre grad på enkeltobjekter. For de fleste planer og konsekvensutredninger vil de foreligge et tilsvarende kulturminnegrunnlag med lik disposisjon og innholdsrekkefølge. Kulturminnegrunnlagene utarbeidet av Byantikvaren, Byrådsavdeling for Byutvikling, benyttes som underlagsmateriale for videre planarbeid. Det skal også ligge som vedlegg til disse planene frem til politisk behandling, og vil inngå som grunnlagsmateriale for senere saksbehandling innen planområdet. Byantikvaren benytter kulturminnegrunnlagene som underlag for kulturminneplanlegging og saksbehandling knyttet til vern av kulturminner og kulturmiljø. I dette kulturminnegrunnlaget er det i hovedsak fjellområdene som beskrives. Her har det vært en kraftig gjengroing som skyldes at skoggrensen kryper høyere, men også manglende uthogging. Derfor er mange av kulturminnestrukturene ikke lenger synlige og heller ikke registrert. Samtidig er det i fjellområdene relativt få spor etter menneskelig aktivitet, men likevel finnes der noen historiefortellende strukturer. Dette er ulike kulturminnestrukturer og spor etter menneskelig aktivitet som er avsatt i området, og som er med på å beskrive og forstå ulik bruk gjennom tidene. Disse sporene er en kilde til kunnskap og opplevelse, og er dermed med på å gi området en økt bruksverdi. -

Fjaler Kyrkjeblad Desember 2014

2 Kyrkjelydsblad for Fjaler Lyset skin i mørkret Den kjende målaren Rembrandt har laga eit bilete av stallen i mørke er at vi har mist kontakten med skaparen. Den Vonde Betlehem som har gjort eit sterkt inntrykk på meg. Biletet viser har fått oss til å tru at vi lever best når vi er våre eigne herrar, eit svært fattigsleg rom der det ikkje kjem inn lys utanfrå. Lyset utan Gud. Difor vert mørkret avslørt når skaparen sjølv stig som gjer at det er råd å skilja personane på biletet, kjem frå inn i vår verd. barnet som ligg i krubba og lyser. Maria og Josef, hyrdin- gane og dyra i stallen, får alle sitt lys frå barnet. “Han kom til sitt eige, og hans eigne tok ikkje i mot han”. Slik var det den fyrste julenatt. Juleevangeliet seier det slik: “Det var ikkje husrom for dei.” Men det store underet, som vi aldri vert ferdige med å undra oss over og gle oss over, er at han kom likevel. Han let seg ikkje stogga av våre stengde dører. Julenatt ligg han der i krubba og kastar sitt lys over oss, ved at han kjem sjølv inn i vår mørke verd som eit hjelpelaust menneskebarn. Han lyser for oss som frelsaren. Dette lyset opplevde mange sjuke, hjelpelause og utstøytte menneske som seinare møtte Jesus. Og det same lyset strålar frå Golgata, der Jesus andar ut på krossen med orda “Det er fullført” på leppene sine. Fyrst der anar vi den djupaste grunnen til at han kom. Han kom for å ta det store oppgjerd med vårt fråfall som ingen av oss er i stand til å ta. -

Odda 2-Dagars 2017 Resultat 3-Kamp

Odda 2-dagars 2017 Resultat 3-kamp Plass Namn Klubb Løype 1 Løype 2 Løype 3 Totaltid B-Open Løype 1 Løype 2 Løype 3 Totaltid 1 Ylva Svanberg Helle TIF Viking 02:42 03:20 02:49 08:51 2 Bjørg Kocbach Bergens TF 03:12 04:39 03:45 11:36 3 Kjetil Hjelle Fitjar IL 03:01 03:50 05:16 12:07 4 Trude Kyrkjebø TIF Viking 03:42 04:17 04:23 12:22 5 Kari Secher Bergens TF 04:17 05:54 04:47 14:58 6 Torild Myrli TIF Viking 07:35 05:19 04:16 17:10 C-Open Løype 1 Løype 2 Løype 3 Totaltid 1 Lisa Bakkejord IL Gular 01:57 02:22 02:26 06:45 2 Mette Fitjar Fitjar IL 02:02 03:00 03:38 08:40 3 Olve Hekland IL Gular 02:53 06:21 04:06 13:20 4 Ingrid Roll Fana IL 04:38 07:35 05:25 17:38 D11-12 Løype 1 Løype 2 Løype 3 Totaltid 1 Idun Hekland IL Gular 02:23 04:45 04:01 11:09 2 Karina Solheim Øyre Odda OL 05:00 05:02 02:44 12:46 D13-14 Løype 1 Løype 2 Løype 3 Totaltid 1 Marie Roll-Tørnquist Fana IL 02:11 02:50 03:33 08:34 2 Kristine Bog Vikane Fana IL 03:06 03:30 03:52 10:28 3 Oda Kjellevold Malde IL Gular 02:49 05:17 03:22 11:28 4 Guro Femsteinevik Varegg Fleridrett 02:29 03:08 06:09 11:46 D15-16 Løype 1 Løype 2 Løype 3 Totaltid 1 Mari Fjellbirkeland Johannesen IL Gular 02:18 03:03 03:24 08:45 2 Tora Aasheim Nymark TIF Viking 05:09 03:20 03:36 12:05 3 Ida Solheim Eide Odda OL 03:35 04:32 04:36 12:43 4 Tiril Olausen Haugesund IL 06:25 05:04 05:47 17:16 D17 Løype 1 Løype 2 Løype 3 Totaltid 1 Anne Kari Vikingstad Torvastad IL 02:18 02:43 02:47 07:48 2 Ingvild Paulsen Vie Haugesund IL 02:09 02:39 03:02 07:50 3 Kristina Voll Haugesund IL 02:12 02:47 02:53 07:52 4 Tonje -

Virginia Viking May 2019

May 2019 Volume 42 No. 14 VIRGINIA VIKING SONS OF NORWAY HAMPTON ROADS LODGE NO. 3-522 President: Leonard Zingarelli Vice President: Mike Solhaug Secretary: June Cooper Treasurer: Ragnhild Zingler The President’s Corner MAY 16, 2019 Membership Meeting at Bayside We are quickly approaching another summer season. Since so Presbyterian Church at 7:30 pm. many of us are away or doing outside activities during the The program is “the First Shot – Norwegians sink the German summer, we always change up our lodge’s routine a little to Heavy Cruiser SMS Bucher. accommodate. For example, we do not hold any business lodge meetings during the summer and suspend our Virginia May 17, 2019 Viking newsletter. Lay Flowers at Forest Lawn Both will resume in September. We do however continue to hold monthly Cemetery at 10:45 am. Membership Lunch at noon at Board meetings that are opened to the general membership. These board Freemason Abbey Restaurant in meeting dates and times can be found on our lodge’s schedule of events. With Norfolk. only a few weeks left in this spring season, the lodge does have several events that you would enjoy. Starting with the Laying of the Flowers at the Forest Lawn May 23, 2019 Cemetery in Norfolk. A remarkable story and how we honor two Norwegian Norwegian National Day Celebration at the Princess Anne sailors that died and buried in Norfolk back during World War Two. We are also Country Club in Virginia Beach. invited to attend the celebration of the Norwegian National Day at Princess Hosted by the Norwegian Nato Anne Country Club. -

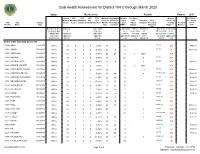

District 104 C.Pdf

Club Health Assessment for District 104 C through March 2020 Status Membership Reports Finance LCIF Current YTD YTD YTD YTD Member Avg. length Months Yrs. Since Months Donations Member Members Members Net Net Count 12 of service Since Last President Vice Since Last for current Club Club Charter Count Added Dropped Growth Growth% Months for dropped Last Officer Rotation President Activity Account Fiscal Number Name Date Ago members MMR *** Report Reported Report *** Balance Year **** Number of times If below If net loss If no report When Number Notes the If no report on status quo 15 is greater in 3 more than of officers that in 12 within last members than 20% months one year repeat do not have months two years appears appears appears in appears in terms an active appears in in brackets in red in red red red indicated Email red Clubs more than two years old 19560 ARNA 11/13/1970 Active 10 0 0 0 0.00% 10 14 MC,SC N/R $400.65 19562 ASKØY 03/08/1967 Active 37 0 2 -2 -5.13% 38 7 4 MC,SC 24+ $1531.86 31071 AUSTEVOLL 07/01/1975 Active 51 1 3 -2 -3.77% 52 27 0 1 None N/R 19565 BERGEN 05/23/1951 Active 15 0 0 0 0.00% 15 16 7 MC,SC N/R 19561 BERGEN ÅSANE 07/01/1966 Active 24 1 2 -1 -4.00% 26 4 2 2 MC,SC N/R $328.86 88725 BERGEN STUDENT 06/23/2005 Active 2 0 0 0 0.00% 2 20 3 None N/R 19566 BERGEN/BERGENHUS 09/14/1966 Active 25 0 0 0 0.00% 26 9 13 MC,SC N/R $5683.62 31166 BERGEN/BJØRGVIN 09/10/1975 Active 18 0 1 -1 -5.26% 19 44 0 4 M,VP,MC,SC N/R $121.80 28228 BERGEN/LØVSTAKKEN 03/22/1974 Active 21 0 1 -1 -4.55% 22 30 5 MC,SC N/R $164.43 19567 BERGEN/ULRIKEN -

Clothing Terms from Around the World

Clothing terms from around the world A Afghan a blanket or shawl of coloured wool knitted or crocheted in strips or squares. Aglet or aiglet is the little plastic or metal cladding on the end of shoelaces that keeps the twine from unravelling. The word comes from the Latin word acus which means needle. In times past, aglets were usually made of metal though some were glass or stone. aiguillette aglet; specifically, a shoulder cord worn by designated military aides. A-line skirt a skirt with panels fitted at the waist and flaring out into a triangular shape. This skirt suits most body types. amice amice a liturgical vestment made of an oblong piece of cloth usually of white linen and worn about the neck and shoulders and partly under the alb. (By the way, if you do not know what an "alb" is, you can find it in this glossary...) alb a full-length white linen ecclesiastical vestment with long sleeves that is gathered at the waist with a cincture aloha shirt Hawaiian shirt angrakha a long robe with an asymmetrical opening in the chest area reaching down to the knees worn by males in India anklet a short sock reaching slightly above the ankle anorak parka anorak apron apron a garment of cloth, plastic, or leather tied around the waist and used to protect clothing or adorn a costume arctic a rubber overshoe reaching to the ankle or above armband a band usually worn around the upper part of a sleeve for identification or in mourning armlet a band, as of cloth or metal, worn around the upper arm armour defensive covering for the body, generally made of metal, used in combat. -

Con!Nui" of Norwegian Tradi!On in #E Pacific Nor#West

Con!nui" of Norwegian Tradi!on in #e Pacific Nor#west Henning K. Sehmsdorf Copyright 2020 S&S Homestead Press Printed by Applied Digital Imaging Inc, Bellingham, WA Cover: 1925 U.S. postage stamp celebrating the centennial of the 54 ft (39 ton) sloop “Restauration” arriving in New York City, carrying 52 mostly Norwegian Quakers from Stavanger, Norway to the New World. Table of Con%nts Preface: 1-41 Immigra!on, Assimila!on & Adapta!on: 5-10 S&ried Tradi!on: 11-281 1 Belief & Story 11- 16 / Ethnic Jokes, Personal Narratives & Sayings 16-21 / Fishing at Røst 21-23 / Chronicats, Memorats & Fabulats 23-28 Ma%rial Culture: 28-96 Dancing 24-37 / Hardanger Fiddle 37-39 / Choral Singing 39-42 / Husflid: Weaving, Knitting, Needlework 42-51 / Bunad 52-611 / Jewelry 62-7111 / Boat Building 71-781 / Food Ways 78-97 Con!nui": 97-10211 Informants: 103-10811 In%rview Ques!onnaire: 109-111111 End No%s: 112-1241111 Preface For the more than three decades I taught Scandinavian studies at the University of Washington in Seattle, I witnessed a lively Norwegian American community celebrating its ethnic heritage, though no more than approximately 1.5% of self-declared Norwegian Americans, a mere fraction of the approximately 280,000 Americans of Norwegian descent living in Washington State today, claim membership in ethnic organizations such as the Sons of Norway. At musical events and dances at Leikarringen and folk dance summer camps; salmon dinners and traditional Christmas celebrations at Leif Ericsson Lodge; cross-country skiing at Trollhaugen near Stampede -

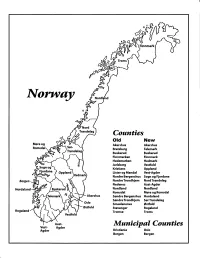

Norway Maps.Pdf

Finnmark lVorwny Trondelag Counties old New Akershus Akershus Bratsberg Telemark Buskerud Buskerud Finnmarken Finnmark Hedemarken Hedmark Jarlsberg Vestfold Kristians Oppland Oppland Lister og Mandal Vest-Agder Nordre Bergenshus Sogn og Fjordane NordreTrondhjem NordTrondelag Nedenes Aust-Agder Nordland Nordland Romsdal Mgre og Romsdal Akershus Sgndre Bergenshus Hordaland SsndreTrondhjem SorTrondelag Oslo Smaalenenes Ostfold Ostfold Stavanger Rogaland Rogaland Tromso Troms Vestfold Aust- Municipal Counties Vest- Agder Agder Kristiania Oslo Bergen Bergen A Feiring ((r Hurdal /\Langset /, \ Alc,ersltus Eidsvoll og Oslo Bjorke \ \\ r- -// Nannestad Heni ,Gi'erdrum Lilliestrom {", {udenes\ ,/\ Aurpkog )Y' ,\ I :' 'lv- '/t:ri \r*r/ t *) I ,I odfltisard l,t Enebakk Nordbv { Frog ) L-[--h il 6- As xrarctaa bak I { ':-\ I Vestby Hvitsten 'ca{a", 'l 4 ,- Holen :\saner Aust-Agder Valle 6rrl-1\ r--- Hylestad l- Austad 7/ Sandes - ,t'r ,'-' aa Gjovdal -.\. '\.-- ! Tovdal ,V-u-/ Vegarshei I *r""i'9^ _t Amli Risor -Ytre ,/ Ssndel Holt vtdestran \ -'ar^/Froland lveland ffi Bergen E- o;l'.t r 'aa*rrra- I t T ]***,,.\ I BYFJORDEN srl ffitt\ --- I 9r Mulen €'r A I t \ t Krohnengen Nordnest Fjellet \ XfC KORSKIRKEN t Nostet "r. I igvono i Leitet I Dokken DOMKIRKEN Dar;sird\ W \ - cyu8npris Lappen LAKSEVAG 'I Uran ,t' \ r-r -,4egry,*T-* \ ilJ]' *.,, Legdene ,rrf\t llruoAs \ o Kirstianborg ,'t? FYLLINGSDALEN {lil};h;h';ltft t)\l/ I t ,a o ff ui Mannasverkl , I t I t /_l-, Fjosanger I ,r-tJ 1r,7" N.fl.nd I r\a ,, , i, I, ,- Buslr,rrud I I N-(f i t\torbo \) l,/ Nes l-t' I J Viker -- l^ -- ---{a - tc')rt"- i Vtre Adal -o-r Uvdal ) Hgnefoss Y':TTS Tryistr-and Sigdal Veggli oJ Rollag ,y Lvnqdal J .--l/Tranbv *\, Frogn6r.tr Flesberg ; \. -

Administrative and Statistical Areas English Version – SOSI Standard 4.0

Administrative and statistical areas English version – SOSI standard 4.0 Administrative and statistical areas Norwegian Mapping Authority [email protected] Norwegian Mapping Authority June 2009 Page 1 of 191 Administrative and statistical areas English version – SOSI standard 4.0 1 Applications schema ......................................................................................................................7 1.1 Administrative units subclassification ....................................................................................7 1.1 Description ...................................................................................................................... 14 1.1.1 CityDistrict ................................................................................................................ 14 1.1.2 CityDistrictBoundary ................................................................................................ 14 1.1.3 SubArea ................................................................................................................... 14 1.1.4 BasicDistrictUnit ....................................................................................................... 15 1.1.5 SchoolDistrict ........................................................................................................... 16 1.1.6 <<DataType>> SchoolDistrictId ............................................................................... 17 1.1.7 SchoolDistrictBoundary ........................................................................................... -

Lagsblad for Leikanger Skyttarlag • Desember 2020 Meir Fart, Meir Moro! 2

LAGSBLAD FOR LEIKANGER SKYTTARLAG • DESEMBER 2020 MEIR FART, MEIR MORO! 2 FIBERNETT på arbeid, heime og hytta Kontakt oss for meir informasjon: sognenett.no | [email protected] | 9519 2222 SKYTELAPPEN LAGSBLAD FOR LEIKANGER SKYTTARLAG 2020 Leikanger skyttarlag sender også i år lagsbladet sitt Skytelappen til alle innbyggarar i gamle Leikanger kommune. Gjennom eit slikt blad får me orientera om tilboda og aktiviteten vår, og dei ulike ANSVARLEG UTGIVAR. årgangane kan vera gode å ha om me vil Leikanger skyttarlag v/styret. Postadresse: 6863 Leikanger sjå tilbake på tidlegare hendingar, bilete og * resultat. BANK: Sparebanken Sogn og Fjordane Konto nr.: 3781.07.31045 Første utgåve av Skytelappen kom i 1984, Heimeside: www.dfs.no/leikanger så dette blir vel 37. årgang. e-post: [email protected] SATS, MONTASJE OG TRYKK: INGVALD HUSABØ PRENTEVERK, LEIKANGER De finn alle blada på laget si heimeside www.dfs.no/leikanger under fana Klasseførde «Om Leikanger». skyttarar i 2021 Skyttarlaget rettar stor takk til Ingvald Tala i klamme gjeld klassesetting for 15 meter innandørs. Husabø Prenteverk for støtte, deira Klasse 5 Arnhild Eiken, Svein Kåre Furre profesjonelle hjelp gjer det muleg å få eit Klasse 4 Vidar Skarsbø Dale, Stine Njøs Eikeland (5), Gaute blad med så høg teknisk kvalitet. Eliassen Hamre, Oliver Karelius Prøven, Eivind Yttri. Klasse 3 Jomar Skarsbø Dale, Atle Henning Lunde (4), Helena Sæbø Nes (4), Malin Sæbø Nes, Janne Humlestøl Njøs (4), Trine Humlestøl Njøs (4), Ørjan Næss, Redaksjonen ynskjer alle ei god jul Jostein Odd, Gabriel Skjulhaug Yttri, Torbjørn Aase. Klasse 2 og eit godt nytt år! Janne Marita Bergheim (3), Gunnar Hamre, Steinar 3 Husabø, Ivar Husum, Linda Furre Lunde, Eirik Håland Moen (3), Håkon Nesse, Camilla Njøs, Jørn Njøs (3), Kjell Nornes, Linn Marita Næss, Yngve Næss, Helsing Leif Arne Stadheim, Odd Rune Våge, Arve Yttri, Siv Kristin Laberg Yttri, Frode Ølmheim, Nils Olav Øy. -

SPECIAL ANNUAL YEARBOOK EDITION Featuring Bilateral Highlights of 27 Countries Including M FABRICS M FASHIONS M NATIONAL DRESS

Published by Issue 57 December 2019 www.indiplomacy.com SPECIAL ANNUAL YEARBOOK EDITION Featuring Bilateral Highlights of 27 Countries including m FABRICS m FASHIONS m NATIONAL DRESS PLUS: SPECIAL COUNTRY SUPPLEMENT Historic Singapore President’s First State Visit to the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia CONTENTS www.indiplomacy.com PUBLISHER’S NOTE Ringing in 2020 on a Positive Note 2 PUBLISHER Sun Media Pte Ltd EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Nomita Dhar YEARBOOK SECTION EDITORIAL Ranee Sahaney, Syed Jaafar Alkaff, Nishka Rao Participating foreign missions share their highlights DESIGN & LAYOUT Syed Jaafar Alkaff, Dilip Kumar, of the year and what their countries are famous for 4 - 56 Roshen Singh PHOTO CONTRIBUTOR Michael Ozaki ADVERTISING & MARKETING Swati Singh PRINTING Times Printers Print Pte Ltd SPECIAL COUNTRY SUPPLEMENT A note about Page 46 PHOTO SOURCES & CONTRIBUTORS Sun Media would like to thank - Ministry of Communications & Information, Singapore. Singapore President’s - Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Singapore. - All the foreign missions for use of their photos. Where ever possible we have tried to credit usage Historic First State Visit and individual photographers. to Saudi Arabia PUBLISHING OFFICE Sun Media Pte Ltd, 20 Kramat Lane #01-02 United House, Singapore 228773 Tel: (65) 6735 2972 / 6735 1907 / 6735 2986 Fax: (65) 6735 3114 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.indiplomacy.com MICA (P) 071/08/2019 © Copyright 2020 by Sun Media Pte Ltd. The opinions, pronouncements or views expressed or implied in this publication are those of contributors or authors. They do not necessarily reflect the official stance of the Indonesian authorities nor their agents and representatives.