President Truman and the Steel Seizure Case: a 50-Year Retrospective - Transcript of Proceedings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Montgomery Ward Case, WTCN Radio Broadcast, May 5, 1944

MONTGOMERY --WARD CASE Broadcast by H. H. Humphrey, Jr. W.T.C.N. May 5, 1944. Montgomery Ward 1 s highly controversial quarrel with the admini- stration got a helping hand from Congress today. The House gave overwhelming approval to a resolution authorizing an investigation of the government's seizure of Montgomery Ward's Chicago plant. The legislators approved the investigation by a vote of three hundred to sixty. The House probe will run concurrently with the Senate inves- tigation already underway. Only the staunchest administration supporters opposed the House resolution calling for a seven-man eo~ttee to decide whether the President exceeded bi s a uthority in ordering the seizure. Adminis- tration stalwarts say the seizure was in accordance with provisions of the Smith-Connally Anti-Strike Law. I wish to take the liberty tonight to give an analysis of this extremely interesting episode in war-time controls by cur government. There seems ~ be an unusually great interest in the government's seizure of the Montgomery Ward plant in Chicago. The s]i8ctacle of Mr. Avery, manager of Ward's, being carried from his office by American soldiers is a milestone in the battle between the Company and the Government. Congress, or some members of Congress, is up in arms. The wildest sort of charges have been hurled at President Roosevelt and Attorney General Biddle. There is plenty o:f smoke and heat, but how about the f'acts. What is the 'record behind the government's seizure? What is Mr. Avery's record in industrial relations? After considerable research and investigation, I have found suf- ficient information to be worthy of presentation. -

Fortress of Liberty: the Rise and Fall of the Draft and the Remaking of American Law

Fortress of Liberty: The Rise and Fall of the Draft and the Remaking of American Law Jeremy K. Kessler∗ Introduction: Civil Liberty in a Conscripted Age Between 1917 and 1973, the United States fought its wars with drafted soldiers. These conscript wars were also, however, civil libertarian wars. Waged against the “militaristic” or “totalitarian” enemies of civil liberty, each war embodied expanding notions of individual freedom in its execution. At the moment of their country’s rise to global dominance, American citizens accepted conscription as a fact of life. But they also embraced civil liberties law – the protections of freedom of speech, religion, press, assembly, and procedural due process – as the distinguishing feature of American society, and the ultimate justification for American military power. Fortress of Liberty tries to make sense of this puzzling synthesis of mass coercion and individual freedom that once defined American law and politics. It also argues that the collapse of that synthesis during the Cold War continues to haunt our contemporary legal order. Chapter 1: The World War I Draft Chapter One identifies the WWI draft as a civil libertarian institution – a legal and political apparatus that not only constrained but created new forms of expressive freedom. Several progressive War Department officials were also early civil libertarian innovators, and they built a system of conscientious objection that allowed for the expression of individual difference and dissent within the draft. These officials, including future Supreme Court Justices Felix Frankfurter and Harlan Fiske Stone, believed that a powerful, centralized government was essential to the creation of a civil libertarian nation – a nation shaped and strengthened by its diverse, engaged citizenry. -

A Counterintelligence Reader, Volume 2 Chapter 1, CI in World

CI in World War II 113 CHAPTER 1 Counterintelligence In World War II Introduction President Franklin Roosevelts confidential directive, issued on 26 June 1939, established lines of responsibility for domestic counterintelligence, but failed to clearly define areas of accountability for overseas counterintelligence operations" The pressing need for a decision in this field grew more evident in the early months of 1940" This resulted in consultations between the President, FBI Director J" Edgar Hoover, Director of Army Intelligence Sherman Miles, Director of Naval Intelligence Rear Admiral W"S" Anderson, and Assistant Secretary of State Adolf A" Berle" Following these discussions, Berle issued a report, which expressed the Presidents wish that the FBI assume the responsibility for foreign intelligence matters in the Western Hemisphere, with the existing military and naval intelligence branches covering the rest of the world as the necessity arose" With this decision of authority, the three agencies worked out the details of an agreement, which, roughly, charged the Navy with the responsibility for intelligence coverage in the Pacific" The Army was entrusted with the coverage in Europe, Africa, and the Canal Zone" The FBI was given the responsibility for the Western Hemisphere, including Canada and Central and South America, except Panama" The meetings in this formative period led to a proposal for the organization within the FBI of a Special Intelligence Service (SIS) for overseas operations" Agreement was reached that the SIS would act -

Clifton Truman Daniel's Visit to Oak Ridge and Y‐12, Part 2

Clifton Truman Daniel’s visit to Oak Ridge and Y‐12, part 2 President Harry S. Truman’s grandson, Clifton Truman Daniel, after visiting Japan to attend an anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, recently visited Oak Ridge to learn the history of the place where the uranium 235 was separated for Little Boy, the world’s first atomic bomb used in warfare, and the world’s first uranium reactor to produce plutonium. He also wanted to understand the history of Oak Ridge since the Manhattan Project. It was this uranium 235 and the plutonium from Hanford, WA, that resulted in President Truman’s decision to use atomic bombs to end World War II. This momentous decision accepted as necessary to stop the horrible killing of World War II by Truman has been called the most controversial decision in history. Clifton was six years old before he realized that his “grandpa” had actually been president of the United States and was only 15 years old when former President Harry S. Truman died. Yet, he has taken an active role in the Harry S. Truman Library and Museum as honorary Chair of the Board of Directors. It is an important function that he says he is proud to fulfill. He has also written two books about his famous grandfather and now has accepted a grant to write another book that goes well beyond President Truman’s life to the study of the long‐term impact of his decision to use atomic bombs to end World War II. This project is what brought him to Oak Ridge and will take him to other Manhattan Project sites as well as other visits to Japan where he will seek survivors of the atomic bombs or their families and seek to understand their stories. -

19856492.Pdf

The Harry S. Truman Library Institute, a 501(c)(3) organization, is dedicated to the preservation, advancement, and outreach activities of the Harry S. Truman Library and Museum, one of our nation’s 12 presidential libraries overseen by the National Archives and Records Administration. Together with its public partner, the Truman Library Institute preserves the enduring legacy of America’s 33rd president to enrich the public’s understanding of history, the presidency, public policy, and citizenship. || executive message DEAR COLLEAGUES AND FRIENDS, Harry Truman’s legacy of decisive and principled leadership was frequently in the national spotlight during 2008 as the nation noted the 60th anniversaries of some of President Truman’s most historic acts, including the recognition of Israel, his executive order to desegregate the U.S. Armed Forces, the Berlin Airlift, and the 1948 Whistle Stop campaign. We are pleased to share highlights of the past year, all made possible by your generous support of the Truman Library Institute and our mission to advance the Harry S. Truman Library and Museum. • On February 15, the Truman Library opened a new exhibit on Truman’s decision to recognize the state of Israel. Truman and Israel: Inside the Decision was made possible by The Sosland Foundation and The Jacob & Frances O. Brown Family Fund. A traveling version of the exhibit currently is on display at the Harry S. Truman Institute for the Advancement of Peace, The Hebrew University, Jerusalem, Israel. • The nation bade a sad farewell to Margaret Truman Daniel earlier this year. A public memorial The Harry S. Truman service was held at the Truman Library on February 23, 2008; she and her husband, Clifton Daniel, were laid to rest in the Courtyard near the President and First Lady. -

Harry S. Truman and the Fight Against Racial Discrimination

“Everything in My Power”: Harry S. Truman and the Fight Against Racial Discrimination by Joseph Pierro Thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in History Peter Wallenstein, Chairman Crandall Shifflett Daniel B. Thorp 3 May 2004 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: civil rights, discrimination, equality, race, segregation, Truman “Everything in My Power”: Harry S. Truman and the Fight Against Racial Discrimination by Joseph Pierro Abstract Any attempt to tell the story of federal involvement in the dismantling of America’s formalized systems of racial discrimination that positions the judiciary as the first branch of government to engage in this effort, identifies the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision as the beginning of the civil rights movement, or fails to recognize the centrality of President Harry S. Truman in the narrative of racial equality is in error. Driven by an ever-increasing recognition of the injustices of racial discrimination, Truman offered a comprehensive civil rights program to Congress on 2 February 1948. When his legislative proposals were rejected, he employed a unilateral policy of action despite grave political risk, and freed subsequent presidential nominees of the Democratic party from its southern segregationist bloc by winning re-election despite the States’ Rights challenge of Strom Thurmond. The remainder of his administration witnessed a multi-faceted attack on prejudice involving vetoes, executive orders, public pronouncements, changes in enforcement policies, and amicus briefs submitted by his Department of Justice. The southern Democrat responsible for actualizing the promises of America’s ideals of freedom for its black citizens is Harry Truman, not Lyndon Johnson. -

The Kennedy Administration's Alliance for Progress and the Burdens Of

The Kennedy Administration’s Alliance for Progress and the Burdens of the Marshall Plan Christopher Hickman Latin America is irrevocably committed to the quest for modernization.1 The Marshall Plan was, and the Alliance is, a joint enterprise undertaken by a group of nations with a common cultural heritage, a common opposition to communism and a strong community of interest in the specific goals of the program.2 History is more a storehouse of caveats than of patented remedies for the ills of mankind.3 The United States and its Marshall Plan (1948–1952), or European Recovery Program (ERP), helped create sturdy Cold War partners through the economic rebuilding of Europe. The Marshall Plan, even as mere symbol and sign of U.S. commitment, had a crucial role in re-vitalizing war-torn Europe and in capturing the allegiance of prospective allies. Instituting and carrying out the European recovery mea- sures involved, as Dean Acheson put it, “ac- tion in truly heroic mold.”4 The Marshall Plan quickly became, in every way, a paradigmatic “counter-force” George Kennan had requested in his influential July 1947 Foreign Affairs ar- President John F. Kennedy announces the ticle. Few historians would disagree with the Alliance for Progress on March 13, 1961. Christopher Hickman is a visiting assistant professor of history at the University of North Florida. I presented an earlier version of this paper at the 2008 Policy History Conference in St. Louis, Missouri. I appreciate the feedback of panel chair and panel commentator Robert McMahon of The Ohio State University. I also benefited from the kind financial assistance of the John F. -

Presidential Leadership and Civil Rights Lawyering in the Era Before Brown

Indiana Law Journal Volume 85 Issue 4 Article 14 Fall 2010 Presidential Leadership and Civil Rights Lawyering in the Era Before Brown Lynda G. Dodd City University of New York Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj Part of the Civil Law Commons, Education Law Commons, and the Law and Politics Commons Recommended Citation Dodd, Lynda G. (2010) "Presidential Leadership and Civil Rights Lawyering in the Era Before Brown," Indiana Law Journal: Vol. 85 : Iss. 4 , Article 14. Available at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj/vol85/iss4/14 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Presidential Leadership and Civil Rights Lawyering in the Era Before Brownt LYNDA G. DODD* INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................1599 I. THE DAWNING OF A NEW CIVIL RIGHTS ERA ...................................................1607 A. WORLD WAR II AND THE MOBILIZATION OF AFRICAN AMERICANS ......1607 B. THE GROWTH OF THE CIVIL RIGHTS INFRASTRUCTURE .........................1609 II. CIVIL RIGHTS ENFORCEMENT CHALLENGES UNDER TRUMAN ........................1610 A. TRUMAN'S FIRST YEAR IN OFFICE .........................................................1610 B. 1946: RACIAL VIOLENCE AND CALLS FOR JUSTICE ................................1612 III. THE PRESIDENT'S COMMITTEE ON CIVIL RIGHTS ...........................................1618 A. UNDER PRESSURE: TRUMAN CREATES A COMMHITEE ...........................1618 B. CIVIL RIGHTS ENFORCEMENT POLICIES: PROPOSALS FOR REFORM .......1625 C. THE REPORT OF THE PRESIDENT'S COMMITTEE ON CIVIL RIGHTS .........1635 IV. REACTION AND REVOLT: TRUMAN'S CIVIL RIGHTS AGENDA ........................1638 A. -

Roosevelt–Truman American Involvement in World War II and Allied Victory in Europe and in Asia

American History wynn w Historical Dictionaries of U.S. Historical Eras, No. 10 w he 1930s were dominated by economic collapse, stagnation, and mass Tunemployment, enabling the Democrats to recapture the White House and w embark on a period of reform unsurpassed until the 1960s. Roosevelt’s New Deal laid the foundations of a welfare system that was further consolidated by roosevelt–truman roosevelt–truman American involvement in World War II and Allied victory in Europe and in Asia. This economic recovery also brought enormous demographic and social changes, HISTORICAL DICTIONARY OF THE OF DICTIONARY HISTORICAL some of which continued after the war had ended. But further political reform was limited because of the impact of the Cold War and America’s new role as the leading superpower in the atomic age. era Historical Dictionary of the Roosevelt–Truman Era examines signifi cant individuals, organizations, and events in American political, economic, social, and cultural history between 1933 and 1953. The turbulent history of this period is told through the book’s chronology, introductory essay, bibliography, and hundreds of cross-referenced dictionary entries on key people, institutions, events, and other important terms. Neil a. wynn is professor of 20th-century American history at the University of Gloucestershire. HISTORICAL DICTIONARY OF THE w roosevelt–truman w w era For orders and information please contact the publisher Scarecrow Press, Inc. A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefi eld Publishing Group, Inc. COVER DESIGN by Allison Nealon 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200 Lanham, Maryland 20706 ISBN-13: 978-0-8108-5616-5 1-800-462-6420 • fax 717-794-3803 ISBN-10: 0-8108-5616-6 www.scarecrowpress.com 90000 COVER IMAGE: Franklin Delano Roosevelt (right) neil a. -

Students Aren't Just Data Points, but Numbers Do Count

LUMINAFOUNDATIONL U M I N A F Winter 2008 Lessons Students aren’t just data points, but numbers do count Lessons: on the inside Page 4 ’Equity for All’ at USC 12 Page Chicago’s Harry S Truman College Page 22 Tallahassee Community College Writing: Christopher Connell Editing: David S. Powell Editorial assistance: Gloria Ackerson and Dianna Boyce Photography: Shawn Spence Photography Design: Huffine Design Production assistance: Freedonia Studios Printing: Mossberg & Company, Inc. On the cover: Indonesia-born Kristi Dewanti attends Tallahassee Community College, where a concerted emphasis on outcomes data is boosting student success. PRESIDENT’SMESSAGE Our grantees wield ‘a powerful tool:’ data Having spent most of the last two decades as a higher education researcher and analyst, I’ve developed some appreciation for the importance and value of student-outcomes data for colleges and universities. Such information is used for a variety of purposes, from informing collaborative action planning on campus, to the actual implementation of those plans, to the assessment or benchmarking of results based on the work undertaken. Robust, reliable data are vital for institutional decision mak- ing and accountability. Compelling data can be the driving force in fostering a “culture of evidence,” leading to measur- able impacts on students and lasting campus change. Too often, casual observers might think that a data-driven institution is one that focuses mainly on the processes of collection and analysis. But at Lumina Foundation for Education, we have always considered data a power- ful tool to better meet students’ needs. From the Achieving the Dream initiative – which has done ground- breaking work to support data-driven decision making at community col- leges – to the important results that have been attained at minority-serving institutions under the Building Engagement and Attainment for Minority Stu- dents (BEAMS) project, Lumina’s investments in data-driven campus change have been gratifying. -

Inside Look Inspiration Remember

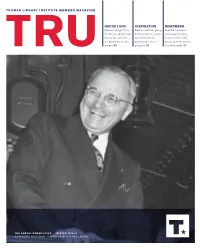

TrumanLibrary.org TRUMAN LIBRARY INSTITUTE INSIDE LOOK INSPIRATION REMEMBER Preview highlights from Meet an ambitious young Read the hometown the Truman Library’s new historian who has grown newspaper’s inspiring Korean War collection up with the Truman memorial to the 33rd in a behind-the-scenes Library’s educational president on the anniver- glimpse. 06 programs. 08 sary of his death. 10 THE ANNUAL DONOR ISSUE WINTER 2018-19 ADVANCING PRESIDENT TRUMAN’S LIBRARY AND LEGACY TRU MAGAZINE THE ANNUAL DONOR ISSUE | WINTER 2018-19 COVER: President Harry S. Truman at the rear of the Ferdinand Magellan train car during Winston Churchill’s visit to Fulton, Missouri, in 1946. Whistle Stop “I’d rather have lasting peace in the world than be president. I wish for peace, I work for peace, and I pray for peace continually.” CONTENTS Highlights 10 12 16 Remembering the 33rd President Harry Truman and Israel Thank You, Donors A look back on Harry Truman’s hometown Dr. Kurt Graham recounts the monumental history A note of gratitude to the generous members and newspaper’s touching memorial of the president. of Truman’s recognition of Israel. donors who are carrying Truman’s legacy forward. TrumanLibraryInstitute.org TRUMAN LIBRARY INSTITUTE 1 MESSAGE FROM EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR 2018 was an auspicious year for Truman anniversaries: 100 years since Captain Truman’s service in World War I and 70 years since some of President Truman’s greatest decisions. These life-changing experiences and pivotal chapters in Truman’s story provided the Harry S. Truman Library and Museum with many meaningful opportunities to examine, contemplate and celebrate the legacy of our nation’s 33rd president. -

Franklin Roosevelt, Thomas Dewey and the Wartime Presidential Campaign of 1944

POLITICS AS USUAL: FRANKLIN ROOSEVELT, THOMAS DEWEY, AND THE WARTIME PRESIDENTIAL CAMPAIGN OF 1944 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. POLITICS AS USUAL: FRANKLIN ROOSEVELT, THOMAS DEWEY AND THE WARTIME PRESIDENTIAL CAMPAIGN OF 1944 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Michael A. Davis, B.A., M.A. University of Central Arkansas, 1993 University of Central Arkansas, 1994 December 2005 University of Arkansas Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the U.S. wartime presidential campaign of 1944. In 1944, the United States was at war with the Axis Powers of World War II, and Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt, already serving an unprecedented third term as President of the United States, was seeking a fourth. Roosevelt was a very able politician and-combined with his successful performance as wartime commander-in-chief-- waged an effective, and ultimately successful, reelection campaign. Republicans, meanwhile, rallied behind New York Governor Thomas E. Dewey. Dewey emerged as leader of the GOP at a critical time. Since the coming of the Great Depression -for which Republicans were blamed-the party had suffered a series of political setbacks. Republicans were demoralized, and by the early 1940s, divided into two general national factions: Robert Taft conservatives and Wendell WiIlkie "liberals." Believing his party's chances of victory over the skilled and wily commander-in-chiefto be slim, Dewey nevertheless committed himself to wage a competent and centrist campaign, to hold the Republican Party together, and to transform it into a relevant alternative within the postwar New Deal political order.