Some Effects of Lysergic Acid Diethylamide on Visual Discrimination in Pigeons Daniel I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inclusion of People of Color in Psychedelic-Assisted Psychotherapy

Michaels et al. BMC Psychiatry (2018) 18:245 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1824-6 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Inclusion of people of color in psychedelic- assisted psychotherapy: a review of the literature Timothy I. Michaels1* , Jennifer Purdon1,2, Alexis Collins1 and Monnica T. Williams1,2 Abstract Background: Despite renewed interest in studying the safety and efficacy of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy for the treatment of psychological disorders, the enrollment of racially diverse participants and the unique presentation of psychopathology in this population has not been a focus of this potentially ground-breaking area of research. In 1993, the United States National Institutes of Health issued a mandate that funded research must include participants of color and proposals must include methods for achieving diverse samples. Methods: A methodological search of psychedelic studies from 1993 to 2017 was conducted to evaluate ethnoracial differences in inclusion and effective methods of recruiting peopple of color. Results: Of the 18 studies that met full criteria (n = 282 participants), 82.3% of the participants were non-Hispanic White, 2.5% were African-American, 2.1% were of Latino origin, 1.8% were of Asian origin, 4.6% were of indigenous origin, 4.6% were of mixed race, 1.8% identified their race as “other,” and the ethnicity of 8.2% of participants was unknown. There were no significant differences in recruitment methodologies between those studies that had higher (> 20%) rates of inclusion. Conclusions: As minorities are greatly underrepresented in psychedelic medicine studies, reported treatment outcomes may not generalize to all ethnic and cultural groups. -

House Bill No. 1176

FIRST REGULAR SESSION HOUSE BILL NO. 1176 101ST GENERAL ASSEMBLY INTRODUCED BY REPRESENTATIVE DAVIS. 2248H.01I DANA RADEMAN MILLER, Chief Clerk AN ACT To repeal sections 191.480 and 579.015, RSMo, and to enact in lieu thereof two new sections relating to investigational drugs. Be it enacted by the General Assembly of the state of Missouri, as follows: Section A. Sections 191.480 and 579.015, RSMo, are repealed and two new sections 2 enacted in lieu thereof, to be known as sections 191.480 and 579.015, to read as follows: 191.480. 1. For purposes of this section, the following terms shall mean: 2 (1) "Eligible patient", a person who meets all of the following: 3 (a) Has a debilitating, life-threatening, or terminal illness; 4 (b) Has considered all other treatment options currently approved by the United States 5 Food and Drug Administration and all relevant clinical trials conducted in this state; 6 (c) Has received a prescription or recommendation from the person's physician for an 7 investigational drug, biological product, or device; 8 (d) Has given written informed consent which shall be at least as comprehensive as the 9 consent used in clinical trials for the use of the investigational drug, biological product, or device 10 or, if the patient is a minor or lacks the mental capacity to provide informed consent, a parent or 11 legal guardian has given written informed consent on the patient's behalf; and 12 (e) Has documentation from the person's physician that the person has met the 13 requirements of this subdivision; 14 (2) "Investigational drug, biological product, or device", a drug, biological product, or 15 device, any of which are used to treat the patient's debilitating, life-threatening, or terminal 16 illness, that has successfully completed phase one of a clinical trial but has not been approved EXPLANATION — Matter enclosed in bold-faced brackets [thus] in the above bill is not enacted and is intended to be omitted from the law. -

Programme & Abstracts

The 57th Annual Meeting of the International Association of Forensic Toxicologists. 2nd - 6th September 2019 BIRMINGHAM, UK The ICC Birmingham Broad Street, Birmingham B1 2EA Programme & Abstracts 1 Thank You to our Sponsors PlatinUm Gold Silver Bronze 2 3 Contents Welcome message 5 Committees 6 General information 7 iCC maps 8 exhibitors list 10 Exhibition Hall 11 Social Programme 14 opening Ceremony 15 Schedule 16 Oral Programme MONDAY 2 September 19 TUESDAY 3 September 21 THURSDAY 5 September 28 FRIDAY 6 September 35 vendor Seminars 42 Posters 46 oral abstracts 82 Poster abstracts 178 4 Welcome Message It is our great pleasure to welcome you to TIAFT Gala Dinner at the ICC on Friday evening. On the accompanying pages you will see a strong the UK for the 57th Annual Meeting of scientific agenda relevant to modern toxicology and we The International Association of Forensic thank all those who submitted an abstract and the Toxicologists Scientific Committees for making the scientific programme (TIAFT) between 2nd and 6th a success. Starting with a large Young Scientists September 2019. Symposium and Dr Yoo Memorial plenary lecture by Prof Tony Moffat on Monday, there are oral session topics in It has been decades since the Annual Meeting has taken Clinical & Post-Mortem Toxicology on Tuesday, place in the country where TIAFT was founded over 50 years Human Behaviour Toxicology & Drug-Facilitated Crime on ago. The meeting is supported by LTG (London Toxicology Thursday and Toxicology in Sport, New Innovations and Group) and the UKIAFT (UK & Ireland Association of Novel Research & Employment/Occupational Toxicology Forensic Toxicologists) and we thank all our exhibitors and on Friday. -

Adverse Reactions to Hallucinogenic Drugs. 1Rnstttutton National Test

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 034 696 SE 007 743 AUTROP Meyer, Roger E. , Fd. TITLE Adverse Reactions to Hallucinogenic Drugs. 1rNSTTTUTTON National Test. of Mental Health (DHEW), Bethesda, Md. PUB DATP Sep 67 NOTE 118p.; Conference held at the National Institute of Mental Health, Chevy Chase, Maryland, September 29, 1967 AVATLABLE FROM Superintendent of Documents, Government Printing Office, Washington, D. C. 20402 ($1.25). FDPS PRICE FDPS Price MFc0.50 HC Not Available from EDRS. DESCPTPTOPS Conference Reports, *Drug Abuse, Health Education, *Lysergic Acid Diethylamide, *Medical Research, *Mental Health IDENTIFIEPS Hallucinogenic Drugs ABSTPACT This reports a conference of psychologists, psychiatrists, geneticists and others concerned with the biological and psychological effects of lysergic acid diethylamide and other hallucinogenic drugs. Clinical data are presented on adverse drug reactions. The difficulty of determining the causes of adverse reactions is discussed, as are different methods of therapy. Data are also presented on the psychological and physiolcgical effects of L.S.D. given as a treatment under controlled medical conditions. Possible genetic effects of L.S.D. and other drugs are discussed on the basis of data from laboratory animals and humans. Also discussed are needs for futher research. The necessity to aviod scare techniques in disseminating information about drugs is emphasized. An aprentlix includes seven background papers reprinted from professional journals, and a bibliography of current articles on the possible genetic effects of drugs. (EB) National Clearinghouse for Mental Health Information VA-w. Alb alb !bAm I.S. MOMS Of NAM MON tMAN IONE Of NMI 105 NUNN NU IN WINES UAWAS RCM NIN 01 NUN N ONMININI 01011110 0. -

EUROPEAN COMMISSION Brussels, 11.7.2011 SEC(2011)

EUROPEAN COMMISSION Brussels, 11.7.2011 SEC(2011) 912 final COMMISSION STAFF WORKING PAPER on the assessment of the functioning of Council Decision 2005/387/JHA on the information exchange, risk assessment and control of new psychoactive substances Accompanying the document REPORT FROM THE COMMISSION on the assessment of the functioning of Council Decision 2005/387/JHA on the information exchange, risk assessment and control of new psychoactive substances {COM(2011) 430 final} EN EN TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction...................................................................................................................3 2. Methodology.................................................................................................................4 3. Key findings from the 2002 evaluation of the Joint Action on synthetic drugs ...........5 4. Overview of notifications, types of substances and trends at EU level 2005-2010......7 5. Other EU legislation relevant for the regulation of new psychoactive substances.....12 6. Functioning of the Council Decision on new psychoactive substances .....................16 7. Findings of the survey among Member States............................................................17 7.1. Assessment of the Council Decision ..........................................................................17 7.2. Stages in the functioning of the Council Decision .....................................................18 7.3. National responses to new psychoactive substances ..................................................20 -

The Effects of Low Dose Lysergic Acid Diethylamide Administration in a Rodent Model of Delay Discounting

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Dissertations Graduate College 6-2020 The Effects of Low Dose Lysergic Acid Diethylamide Administration in a Rodent Model of Delay Discounting Robert J. Kohler Western Michigan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations Part of the Biological Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Kohler, Robert J., "The Effects of Low Dose Lysergic Acid Diethylamide Administration in a Rodent Model of Delay Discounting" (2020). Dissertations. 3565. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations/3565 This Dissertation-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE EFFECTS OF LOW DOSE LYSERGIC ACID DIETHYLAMIDE ADMINISTRATION IN A RODENT MODEL OF DELAY DISCOUNTING by Robert J. Kohler A dissertation submitted to the Graduate College In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Psychology Western Michigan University June 2020 Doctoral Committee: Lisa Baker, Ph.D., Chair Anthony DeFulio, Ph.D. Cynthia Pietras, Ph.D. John Spitsbergen, Ph.D. Copyright by Robert J. Kohler 2020 THE EFFECTS OF LOW DOSE LYSERGIC ACID DIETHYLAMIDE ADMINISTRATION IN A RODENT MODEL OF DELAY DISCOUNTING Robert J. Kohler, Ph.D. Western Michigan University, 2020 The resurgence of Lysergic Acid Diethylamide (LSD) as a therapeutic tool requires a revival in research, both basic and clinical, to bridge gaps in knowledge left from a previous generation of work. Currently, no study has been published with the intent of establishing optimal microdose concentrations of LSD in an animal model. -

A General Approach to the Screening and Confirmation of Tryptamines And

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com Talanta 74 (2008) 512–517 A general approach to the screening and confirmation of tryptamines and phenethylamines by mass spectral fragmentation Bo-Hong Chen a, Ju-Tsung Liu b, Wen-Xiong Chen a, Hung-Ming Chen a, Cheng-Huang Lin a,∗ a Department of Chemistry, National Taiwan Normal University, 88 Sec. 4, Tingchow Road, Taipei, Taiwan b Forensic Science Center, Military Police Command, Department of Defense, Taipei, Taiwan Received 6 March 2007; received in revised form 12 June 2007; accepted 13 June 2007 Available online 19 June 2007 Abstract Certain characteristic fragmentations of tryptamines (indoleethylamine) and phenethylamines are described. Based on the GC–EI/MS, LC–ESI/ MS and MALDI/TOFMS, the mass fragmentations of 13 standard compounds, including ␣-methyltryptamine (AMT), N,N-dimethyltryptamine (DMT), 5-methoxy-␣-methyltryptamine (5-MeO-AMT), N,N-diethyltryptamine (DET), N,N-dipropyltryptamine (DPT), N,N-dibutyltryptamine (DBT), N,N-diisopropyltryptamine (DIPT), 5-methoxy-N,N-dimethyltryptamine (5-MeO-DMT), 5-methoxy-N,N-diisopropyltryptamine (5-MeO- DIPT), methamphetamine (MAMP), 3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine (3,4-MDA), 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (3,4-MDMA) and 2- methylamino-1-(3,4-methylenedioxyphenyl)butane (MBDB), were compared. As a result, the parent ions of these analytes were hard to be obtained by GC/MS whereas the protonated molecular ions can be observed clearly by means of ESI/MS and MALDI/TOFMS. Furthermore, two major + + + + characteristic fragmentations, namely and ␣-cleavage ([M +H] → [3-vinylindole] ) and -cleavage ([M +H] → [CH2N RN1RN2]), are produced when the ESI and MALDI modes are used, respectively. In the case of ESI/MS, the fragment obtained from ␣-cleavage is the major process. -

LSD), Which Produces Illicit Market in the USA

DEPENDENCE LIABILITY OF "NON-NARCOTIC 9 DRUGS 81 INDOLES The prototype drug in this subgroup (Table XVI) potentials. Ibogaine (S 212) has appeared in the is compound S 219, lysergide (LSD), which produces illicit market in the USA. dependence of the hallucinogen (LSD) type (see above). A tremendous literature on LSD exists which documents fully the dangers of abuse, which REFERENCES is now widespread in the USA, Canada, the United 304. Sandoz Pharmaceuticals Bibliography on Psychoto- Kingdom, Australia and many western European mimetics (1943-1966). Reprinted by the US countries (for references see Table XVI). LSD must Department of Health, Education, & Welfare, be judged as a very dangerous substance which has National Institute of Mental Health, Washington, no established therapeutic use. D.C. 305. Cerletti, A. (1958) In: Heim, R. & Wasson, G. R., Substances S 200-S 203, S 206, S 208, S 213-S 218 ed., Les champignons hallucinogenes du Mexique, and S 220-S 222 are isomers or congeners of LSD. pp. 268-271, Museum national d'Histoire natu- A number of these are much less potent than LSD in relle, Paris (Etude pharmacologique de la hallucinogenic effect or are not hallucinogenic at all psilocybine) (compounds S 203, S 213, S 216, S 217, S 220 and 306. Cohen, S. (1965) The beyond within. The LSD S 222) and accordingly carry a lesser degree of risk story. Atheneum, New York than LSD. None of these weak hallucinogens has 307. Cohen, S. & Ditman, K. S. (1963) Arch. gen. been abused. Other compounds are all sufficiently Psychiat., 8, 475 (Prolonged adverse reactions to potent to make it likely that they would be abused if lysergic acid diethylamide) 308. -

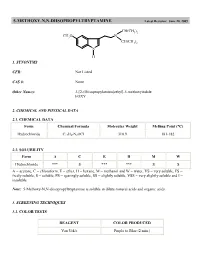

5-METHOXY-N,N-DIISOPROPYLTRYPTAMINE Latest Revision: June 20, 2005

5-METHOXY-N,N-DIISOPROPYLTRYPTAMINE Latest Revision: June 20, 2005 CH(CH3)2 CH3O N CH(CH3)2 N H 1. SYNONYMS CFR: Not Listed CAS #: None Other Names: 3-[2-(Diisopropylamino)ethyl]-5-methoxyindole FOXY 2. CHEMICAL AND PHYSICAL DATA 2.1. CHEMICAL DATA Form Chemical Formula Molecular Weight Melting Point (°C) Hydrochloride C17H27N2OCl 310.9 181-182 2.2. SOLUBILITY Form A C E H M W Hydrochloride *** S *** *** S S A = acetone, C = chloroform, E = ether, H = hexane, M = methanol and W = water, VS = very soluble, FS = freely soluble, S = soluble, PS = sparingly soluble, SS = slightly soluble, VSS = very slightly soluble and I = insoluble Note: 5-Methoxy-N,N-diisopropyltryptamine is soluble in dilute mineral acids and organic acids. 3. SCREENING TECHNIQUES 3.1. COLOR TESTS REAGENT COLOR PRODUCED Van Urk's Purple to Blue (2 min.) 3.2. THIN LAYER CHROMATOGRAPHY Visualization Van Urk's reagent Relative R COMPOUND f System TLC 18 dimethyltryptamine 0.32 diethyltryptamine 0.89 5-methoxy- -methyltryptamine 0.70 5-methoxydiisopropyltryptamine 1.0 (8.05 cm) 3.3. GAS CHROMATOGRAPHY Method DMT-GCS1 Instrument: Gas chromatograph operated in split mode with FID Column: J&W DB-1 15 m x 0.32 mm x 0.25 µm film thickness Carrier gas: Helium at 1.3 mL/min Temperatures: Injector: 275°C Detector: 280°C Oven program: 190°C for 10 min Injection Parameters: Split Ratio = 60:1, 1 µL injected Samples are to be dissolved in chloroform, washed with dilute sodium carbonate and filtered. COMPOUND RRT COMPOUND RRT indole 0.12 DET 0.37 MDA 0.15 C-4 phthalate 0.38 MDMA 0.17 5-MeO-AMT 0.42 tryptamine 0.23 5-MeODMT 0.46 AMT 0.24 DIPT 0.58 DMT 0.26 C-5 phthalate 0.65 caffeine 0.28 5-MeODIPT 1.00 (7.14 min) 4. -

Psychedelic Gospels

The Psychedelic Gospels The Psychedelic Gospels The Secret History of Hallucinogens in Christianity Jerry B. Brown, Ph.D., and Julie M. Brown, M.A. Park Street Press Rochester, Vermont • Toronto, Canada Park Street Press One Park Street Rochester, Vermont 05767 www.ParkStPress.com Park Street Press is a division of Inner Traditions International Copyright © 2016 by Jerry B. Brown and Julie M. Brown All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Note to the Reader: The information provided in this book is for educational, historical, and cultural interest only and should not be construed in any way as advocacy for the use of hallucinogens. Neither the authors nor the publishers assume any responsibility for physical, psychological, legal, or any other consequences arising from these substances. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data [cip to come] Printed and bound in XXXXX 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Text design and layout by Priscilla Baker This book was typeset in Garamond Premier Pro with Albertus and Myriad Pro used as display typefaces All Bible quotations are from the King James Bible Online. A portion of proceeds from the sale of this book will support the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS). Founded in 1986, MAPS is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit research and educational organization that develops medical, legal, and cultural contexts for people to benefit from the careful uses of psychedelics and marijuana. -

Hallucinogens: an Update

National Institute on Drug Abuse RESEARCH MONOGRAPH SERIES Hallucinogens: An Update 146 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services • Public Health Service • National Institutes of Health Hallucinogens: An Update Editors: Geraline C. Lin, Ph.D. National Institute on Drug Abuse Richard A. Glennon, Ph.D. Virginia Commonwealth University NIDA Research Monograph 146 1994 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES Public Health Service National Institutes of Health National Institute on Drug Abuse 5600 Fishers Lane Rockville, MD 20857 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT This monograph is based on the papers from a technical review on “Hallucinogens: An Update” held on July 13-14, 1992. The review meeting was sponsored by the National Institute on Drug Abuse. COPYRIGHT STATUS The National Institute on Drug Abuse has obtained permission from the copyright holders to reproduce certain previously published material as noted in the text. Further reproduction of this copyrighted material is permitted only as part of a reprinting of the entire publication or chapter. For any other use, the copyright holder’s permission is required. All other material in this volume except quoted passages from copyrighted sources is in the public domain and may be used or reproduced without permission from the Institute or the authors. Citation of the source is appreciated. Opinions expressed in this volume are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or official policy of the National Institute on Drug Abuse or any other part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The U.S. Government does not endorse or favor any specific commercial product or company. -

Update of the Generic Definition for Tryptamines

ACMD Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs Chair: Professor Les Iversen Secretary: Zahi Sulaiman 2nd Floor (NW), Seacole Building 2 Marsham Street London SW1P 4DF Tel: 020 7035 1121 [email protected] Norman Baker MP, Minister for Crime Prevention Home Office 2 Marsham Street London SW1P 4DF 10 June 2014 Dear Minister, In December 2013, you commissioned the ACMD to begin a regular review of generic definitions under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971, with the aim of capturing emerging new psychoactive substances. These drugs are variants of controlled drugs and fall outside the existing scope of the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971. The ACMD has considered evidence available on tryptamines in the context of the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 and I enclose the Advisory Council’s advice and an expanded definition for tryptamine compounds with this letter. The ACMD’s NPS Committee has firstly reviewed previous research and existing controls to identify those tryptamines now seen to evade the existing controls. The ACMD has also reviewed data provided by the Home Office’s early warning systems and networks, clinical toxicology, prevalence and neuropharmacology in arriving at the expanded generic definition. This expanded generic definition will bring drugs such as alpha-methyltryptamine (AMT) as well as 5-MeO-DALT within the scope of the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971. These are highly potent hallucinogens which act on the 5HT2A receptor, in the same way as LSD. The ACMD therefore recommends that the tryptamines covered by the proposed expanded generic definition in this report, are controlled under the Misuse of Drugs Act (1971) as Class A substances.