Peter Finer ANTIQUE ARMS and ARMOUR

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Your Kids, Their Swords, and Surviving It All with Your Sanity Intact

The PARENTS’ FENCING SURVIVAL GUIDE 2015 EDITION This is a bit of a read! It won’t send you to sleep but best to dip in as required Use Ctrl+click on a content heading to jump to that section Contents Why Fencing? ........................................................................................................................... 3 How Will Fencing Benefit My Child? ......................................................................................... 4 Fencing: So Many Flavours to Choose From ............................................................................ 4 Is it Safe? (We are talking about sword fighting) ....................................................................... 5 Right-of-What? A List of Important Terms ................................................................................. 6 Overview of the Three Weapons .............................................................................................. 9 Getting Started: Finding Classes ............................................................................................ 12 The Training Diary .................................................................................................................. 12 Getting Started: Basic Skills and Gear .................................................................................... 13 Basic Equipment: A Little more Detail ..................................................................................... 14 Note: Blade Sizes – 5, 3, 2, 0, What? .................................................................................... -

The Seven Sabre Guards for a Right Handed Fencer

The Seven Sabre Guards for a Right handed fencer. st “Prime” 1 Guard or Parry (Hand in Pronation “Quinte” 5th Guard or parry (Hand in Pronation) “Seconde” 2nd Guard or Parry (Hand in Pronation) “Sixte” 6th Guard or Parry (Hand in half Supination) “Tierce” 3rd Guard or Parry (Hand in Pronation) th “Offensive Defensive position” 7 Guard of Parry (Hand in half Pronation) Supination: Means knuckles of the sword hand pointing down. Half Pronation: Means knuckles pointing towards the sword arm side of the body with the thumb on top of the sword handle. Pronation: Means knuckles of the sword hand pointing th “Quarte” 4 Guard or Parry (hand in Half Pronation) upwards. Copyright © 2000 M.J. Dennis Below is a diagram showing where the Six fencing positions for Sabre are assuming the fencer is right handed (sword arm indicated) the Target has been Quartered to show the High and Low line Guards (note the offensive/defensive position is an adaptation of tierce and quarte). Sixte: (Supinated) To protect the head Head Quinte: (Pronation) To protect the head Cheek Cheek High Outside High Inside Tierce: (½ Pronation) to Prime: (Pronation) to protect the sword arm, protect the inside chest, and chest, and cheek. belly. Seconde: (Pronation) Fencers to protect the belly and Quarte: (½ Pronation) To Sword-arm flank protect chest and cheek Flank Low Outside Low Inside Belly The Sabre target is everything above the waist. This includes the arms, hands and head. Copyright © 2000 M.J. Dennis Fencing Lines. Fencing lines can cause a great deal of confusion, so for ease I shall divide them into four separate categories. -

Swordsmanship and Sabre in Fribourg

Acta Periodica Duellatorum, Hands-on section, articles 103 Hands-on section, articles Sweat and Blood: Swordsmanship and sabre in Fribourg Mathijs Roelofsen, PhD Student, University of Bern [email protected], and Dimitri Zufferey, Independant Researcher, GAFSchola Fribourg, [email protected] Abstract – Following a long mercenary tradition, Switzerland had to build in the 19th century its own military tradition. In Cantons that have provided many officers and soldiers in the European Foreign Service, the French military influence remained strong. This article aims to analyze the development of sabre fencing in the canton of Fribourg (and its French influence) through the manuals of a former mercenary (Joseph Bonivini), a fencing master in the federal troops (Joseph Tinguely), and an officer who became later a gymnastics teacher (Léon Galley). These fencing manuals all address the recourse to fencing as physical training and gymnastic exercise, and not just as a combat system in a warlike context. Keywords – Sabre, Fribourg, Valais, Switzerland, fencing, contre-pointe, bayonet I. INTRODUCTION In military history, the Swiss are known for having offered military service as mercenaries over a long time period. In the 19th century, this system was however progressively abandoned, while the country was creating its own national army from the local militias. The history of 19th century martial practices in Switzerland did not yet get much attention from historians and other researchers. This short essay is thus a first attempt to set some elements about fencing in Switzerland at that time, focusing on some fencing masters from one Swiss Canton (Fribourg) through biographical elements and fencing manuals. -

COLD ARMS Zoran Markov Dragutin Petrović

COLD ARMS Zoran Markov Dragutin Petrović MUZEUL BANATULUI TIMIŞOARA 2012 PREFACE Authors of the catalog and exhibition: Zoran Markov, Curator, Banat Museum of Timisoara Dragutin Petrović, Museum - Consultant, The City Museum of Vršac Associates at the exhibition: Vesna Stankov, Etnologist, Senior Curator Dragana Lepir, Historian Reviewer: “Regional Centre for the Heritage of Banat — Concordia” is set adopted a draft strategy for long-term research, protection and pro- Eng. Branko Bogdanović up with funds provided by the EU and the Municipality of Vršac, motion of the cultural heritage of Banat, where Banat means a ge- Catalog design: as a cross-border cooperation project between the City Museum ographical region, which politically belongs to Romania, Hungary Javor Rašajski of Vršac (CMV) and Banat Museum in Timisoara (MBT). In im- and Serbia. Photos: plementation of this project, the reconstruction of the building of All the parts of the Banat region have been inextricably linked Milan Šepecan Concordia has a fundamental role. It will house the Regional Centre by cultural relations since the earliest prehistoric times. Owing to Ivan Kalnak and also be a place for the permanent museum exhibition. its specific geographical position, distinctive features and the criss- Technical editor: The main objective of establishing the Regional Centre in crossing rivers Tisza, Tamis and Karas, as the ways used for spread- Ivan Kalnak Concordia is cross-border cooperation between all institutions of ing influence by a number of different cultures, identified in archae- COLD ARMS culture and science in the task of production of a strategic plan ological research, the area of Banat represents today an inexhaust- and creation of best conditions for the preservation and presenta- ible source of information about cultural and historic ties. -

Introduction to Rapier

INTRODUCTION TO RAPIER Based on the teachings of Ridolfo Capo Ferro, in his treatise first published in 1610. A WORKBOOK By Nick Thomas Instructor and co-founder of the © 2016 Academy of Historical Fencing Version 1 Introduction The rapier is the iconic sword of the renaissance, but it is often misunderstood due to poor representation in popular culture. The reality of the rapier is that it was a brutal and efficient killer. So much so that in Britain it was often considered a bullies or murderers weapon. Because to use a rapier against a person is to attempt to kill them, and not just defend oneself. A result of the heavy emphasis on point work and the horrendous internal damage that such thrust work inflicts. Rapier teachings were first brought to Britain in the 1570’s, and soon became the dominant weapon for civilian wear. Of course many weapons that were not so different were also used in the military, featuring the same guards and slightly lighter and broader blades. The rapier was very commonly used with offhand weapons, and Capo Ferro covers a range of them. However for this work book, we will focus on single sword, which is the foundation of the system. This class is brought to you by the Academy of Historical Fencing (UK) www.historicalfencing.co.uk If you have any questions about the class or fencing practice in general, feel free to contact us – [email protected] Overview of the weapon The First thing to accept as someone who already studies one form or another of European swordsmanship, is that you should not treat the rapier as something alien to you. -

PDF Download Sword and Scimitar Pdf Free Download

SWORD AND SCIMITAR PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Simon Scarrow | 592 pages | 25 Apr 2013 | Headline Publishing Group | 9781472201904 | English | London, United Kingdom Sword and Scimitar PDF Book In Chicago, based on what I hear in sermons, my impression is that Cardinal Cupich has mandated this line of speech. Hwandudaedo Seven- Branched Sword. Thank you for signing up! To view it, click here. Type of Sword. Thank you. Loading Related Books. Reproduction of the original sword from Topkapi Museum, Istanbul. Thus, the Crusaders took the fight across the Mediterranean, a thousand miles away, and mostly prevailed over the Muslim occupiers of territory that Christianity had originally gained by conversion. Richard F. Aug 07, Laura rated it liked it. The Shamshir or sometimes referred to as the Mameluke Sword belongs to the collection of swords of the Seljuk empire, and later on adopted the name Shamshir when the weapon was taken to Persia in the twelfth century. Skip to main content. The stories are told through the eyes of two centurions, Macro and Cato. All of that said it is certainly correct that white slaves were the most prized and again as sex-slaves in the hareems of wealthy Mussalmen; but in terms of sheer numbers the Muslim black slave trade was about an order of magnitude greater than the white one. For other uses, see Scimitar disambiguation. It's against this backdrop that Sir Thomas Barrett, an English knight who had left the Order due to a scandal, finds himself called back into service. Edition Description A sweeping history of the often-violent conflict between Islam and the West, shedding a revealing light on current hostilities The West and Islam--the sword and scimitar--have clashed since the mid-seventh century, when, according to Muslim tradition, the Roman emperor rejected Prophet Muhammad's order to abandon Christianity and convert to Islam, unleashing a centuries-long jihad on Christendom. -

The Fight Master, October 1978, Vol. 1 Issue 3

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Fight Master Magazine The Society of American Fight Directors 10-1978 The Fight Master, October 1978, Vol. 1 Issue 3 The Society of American Fight Directors Follow this and additional works at: https://mds.marshall.edu/fight Part of the Acting Commons, Other Theatre and Performance Studies Commons, Performance Studies Commons, and the Theatre History Commons Recommended Citation The Society of American Fight Directors, "The Fight Master, October 1978, Vol. 1 Issue 3" (1978). Fight Master Magazine. 3. https://mds.marshall.edu/fight/3 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the The Society of American Fight Directors at Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fight Master Magazine by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. the Property of the ~.ltde±ti .of fi9bt J\mericmt Jlfigl1t Ji}tr£cfon_; rnasteu tbe societiY o,i: ameuican ,i:igbt <liuectons '1 IMlt'I' ------------------------------ REPLICA SWORDS 'rhe· Magazine of the Society of American Fight Directors We carry a wide selection of replica No. 3 October 1978 swords for theatrical and decorative use. Editor - Mike McGraw Lay-out - David L. Boushey RECOMMENDED BY THE ,'1 SOCIETY OF AMERICAN FIGHT DIRECTORS Typed and Duplicated by Mike McGraw I *************************************** ~oci~ty of American Yi£ht Directors The second Society of Fight Directors in the world has been I incorporated in Seattle, Washington. Its founder is David I IIi Boushey, Overseas Affiliate of the Society of British Fight ' Directors. OFFICERS: President - David L. -

The Sword and the Scimitar Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE SWORD AND THE SCIMITAR PDF, EPUB, EBOOK David Ball | 784 pages | 05 Aug 2004 | Cornerstone | 9780099457954 | English | London, United Kingdom The Sword and the Scimitar PDF Book Set within wh A powerful historical masterpiece by an accomplished author, who brings history vividly to life in all its vibrancy and grittiness. Packaging should be the same as what is found in a retail store, unless the item is handmade or was packaged by the manufacturer in non-retail packaging, such as an unprinted box or plastic bag. Sep 13, John Cheeseman rated it really liked it. Flag of Hayreddin Barbarossa. Andree Sanborn added it Mar 30, Download as PDF Printable version. He is best known for his "Eagle" series. Etymology Tolkien uses the term "scimitar" to describe any curved blade existing in Middle-earth. Raymond Chandler Paperback Books. In that case, we can't My only criticism is its somewhat dry style; the book reads like a long-form encyclopedia article. I am constantly in awe of how Simon Scarrow writes such starkly poignant and powerfully dramatic stories that reach out to your inmost core, touching you with authenticity, delicate ambience and realism. You know the saying: There's no time like the present The book is a very detailed account of the many battles between the two Abrahamic faiths. Namespaces Article Talk. How the heck is it possible the Islamic world was the torchbearer of science and knowledge for centuries given the realities shared in the book? Refresh and try again. Daily life in the medieval Islamic world. And I'm not a big "We are all the prisoners of our history. -

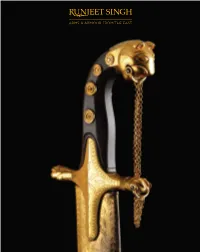

Viewings by Appointment Only 6

+44 (0)7866 424 803 [email protected] runjeetsingh.com CONTENTS Daggers 6 Swords 36 Polearms 62 Firearms 74 Archery 84 Objects 88 Shields 98 Helmets 104 Written by Runjeet Singh Winter 2015 All prices on request Viewings by appointment only 6 1 JAAM-DHAR An important 17th century Indian A third and fourth example are (DEMONS TOOTH) katar (punch dagger) from the published by Elgood 2004, p.162 KATAR Deccan plateau, possibly Golkonda (no.15.39) and Egerton (no.388), (‘shepherd’s hill’), a fort of Southern from Deccan and Lucknow India and capital of the medieval respectively. Both are late 17th DECCAN (SOUTH INDIA) sultanate of the Qutb Shahi dynasty or early 18th century and again 17TH CENTURY (c.1518–1687). follow the design of the katar in this exhibition. OVERALL 460 MM This rare form of Indian katar is the BLADE 280 MM earliest example known from a small The heavy iron hilt has intricate group, examples of which are found piercing and thick silver sheet is in a number of notable collections. applied overall. These piercing, These include no.133 in Islamic suggestive of flower patterns, softens Arms & Armour from Danish private the austerity of the design which Collections, dated to the early 18th can be related to architecture, for century. Probably Deccani in origin, example the flared side bars have the arabesques on the blade have tri-lobed ends. The architectural Shi’ite calligraphy. The features of this theme continues into the lower bar fine katar are closely related to the which connects to the blade; this has katar published here. -

The Use of the Saber in the Army of Napoleon

Acta Periodica Duellatorum, Scholarly Volume, Articles 103 DOI 10.1515/apd-2016-0004 The use of the saber in the army of Napoleon Bert Gevaert Katholieke Universiteit Leuven (Belgium) Hallebardiers / Sint Michielsgilde Brugge (Belgium) [email protected] Abstract – Though Napoleonic warfare is usually associated with guns and cannons, edged weapons still played an important role on the battlefield. Swords and sabers could dominate battles and this was certainly the case in the hands of experienced cavalrymen. In contrast to gunshot wounds, wounds caused by the saber could be treated quite easily and caused fewer casualties. In 18th and 19th century France, not only manuals about the use of foil and epee were published, but also some important works on the military saber: de Saint Martin, Alexandre Muller… The saber was not only used in individual fights against the enemy, but also as a duelling weapon in the French army. Keywords – saber; Napoleonic warfare; Napoleon; duelling; Material culture; Historical European Martial Arts (HEMA); History “The sword is the weapon in which you should have most confidence, because it rarely fails you by breaking in your hands. Its blows are the more certain, accordingly as you direct them coolly; and hold it properly.” Antoine Fortuné de Brack, Light Cavalry Exercises, 18761 I. INTRODUCTION Though Napoleon (1769-1821) started his own military career as an artillery officer and achieved several victories by clever use of cannons, edged weapons still played an important role on the Napoleonic battlefield. Swords and sabers could dominate battles and this was certainly the case in the hands of experienced cavalrymen. -

Western Hemisphere Swords)

53_78_weatherly 12/30/05 9:45 AM Page 53 Swords of the Americas (Western Hemisphere Swords) George E. Weatherly Figure 1. Flags of the Americas. nomenclature of a sword and the unique terminology used to I have been a member of this organization for 25 years, describe it, since these terms will be used throughout this some of you I have known longer than that . It has been presentation. The word sword is commonly used as a generic my privilege to have hosted two meetings, served as term applied to all types of long blade weapons. However, Secretary-treasurer, Vice President, and President of A.S.A.C Webster’s Dictionary defines: . I still have one obligation to fulfill and that is my pur- pose in being here today; to deliver this paper . At this time I would like to introduce you to some of my contributors. (Figures 2 and 3) I am sure that many, if not most of you, know more about swords than I do. But for the few who are unfamiliar with these edged weapons, I would like to briefly review the Figure 3. Emiliano Zapata, Mexican Revolutionary, c1915. Proudly Figure 2. A group of Mexican rurales (local police). holding his lion head sword and Winchester. Reprinted from the American Society of Arms Collectors Bulletin 92:53-78 92/53 Additional articles available at http://americansocietyofarmscollectors.org/resources/articles/ 53_78_weatherly 12/30/05 9:45 AM Page 54 “Patton” model (Figure 5). General George S. Patton was credited with the design. The use of ceremonial swords continues today, i.e., parades and affairs of state. -

Cold Steel: a Practical Treatise on the Sabre

COLD STEEL: A PRACTICAL TREATISE ON THE SABRE. BASED ON THE OLD ENGLISH BACKSWORD PLAY OF THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY COMBINED WITH THE METHOD OF THE MODERN ITALIAN SCHOOL. ASLO ON VARIOUS OTHER WEAPONS OF THE PRESENT DAY, INCLUDING THE SHORT SWORD-BAYONET AND THE CONSTABLE‘S TRUNCHEON BY ALFRED HUTTON LATE CAPT. KING‘S DRAGOON GUARDS; AUTHOR OF ”SWORDSMANSHIP,‘ ”BAYONET-FENCING AND SWORD PRACTICE,‘ ETC. Looxvwudwhg zlwk qxphurxv Iljxuhv0 AND ALSO WITH REPRODUCTIONS OF ENGRAVINGS FROM MASTERS OF BYGONE YEARS. LONDON WILLIAM CLOWES AND SONS, LIMITED 13, CHARING CROSS. 1889. 1 TO P | Iulhqg EGERTON CASTLE, F.S.A. 2 Table of Contents COLD STEEL: A PRACTICAL TREATISE ON THE SABRE.....................................1 Table of Contents...........................................................................................................3 List of Plates ..................................................................................................................6 THE SABRE..................................................................................................................7 THE SABRE..................................................................................................................7 INTRODUCTION. ....................................................................................................7 THE PARTS OF THE SABRE..................................................................................7 HOW TO HOLD THE SABRE.............................................................................7 GUARD. ................................................................................................................8