Let's Play Goalball

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study on the Changes in the Number of Participating Athletes in the National Disabled Games Between 2008 and 2012, Using the Latent Growth Model

A Study on the Changes in the Number of Participating Athletes in the National Disabled Games between 2008 and 2012, Using the Latent Growth Model Cheng-Lung Wu, Department of Marine Sports and Recreation, National Penghu University of Science and Technology, Taiwan ABSTRACT This study employed the Latent Growth Model (LGM) to analyze changes in the number of participating athletes in the National Disabled Games from all cities and counties in Taiwan between 2008 and 2012. The aim was to examine the changes and dynamic process of the participating athletes at different times. The result of the study indicates that between 2008 and 2012, the initial average of the number of participating athletes in the National Disabled Games is 53.23, and the average growth is 3.93; the respective t values are 6.78 and 2.81, which are both statistically significant (*p<.05). In other words, the average number of participating athletes in the National Disabled Games in 2008 was 53.23, and continued to grow at an average rate of 3.93 persons per year. There was significant growth in the number of participating athletes between 2008 and 2012 in all cities and counties. In addition, there was significant difference in the growth rates among different cities and counties. Keywords: Latent Growth Model (LGM), physical and mental impairments, National Disabled Games INTRODUCTION It has become a global trend to improve the welfare of the physically and mentally challenged. The degree to which a country is capable of providing adequate care and opportunities for its physically and mentally challenged citizens is also an important index in evaluating its overall development. -

Boccia Bean Bags, Koosh Balls, Paper & Tape Balls, Fluff Balls

Using the Activity Cards Sports Ability is an inclusive activities program There may be some differences concerning rules, equipment that adopts a social / environmental approach and technique. However, teachers, coaches and sports leaders to inclusion. This approach concentrates on the working in a physical activity and sport setting can treat young people with a disability in a similar way to any of their other ways in which teachers, coaches and sports athletes or students. The different stages of learning and the leaders can adjust, adapt and modify the way in basic techniques of skill teaching apply equally for young people which an activity is delivered rather than focus with disabilities. A teacher, coach or sports leader can ensure on individual disabilities. their approach is inclusive by applying the TREE principle. TREE stands for: Teaching / coaching style Observing, questioning, applying and reviewing. Example: a flexible approach to communication to ensure that information is shared by all. Rules In competitive and small-sided activities. Example: allowing two bounces of the ball in a tennis activity, or more lives for some players in a tag game. Equipment Vary to provide more options. Example: using a brighter coloured ball or a sound ball to assist players with tracking. Environment Space, surface, weather conditions. Example: enabling players with different abilities to play in different sized spaces. TREE can be used as a practical tool and a mental map to help teachers, coaches and Try the suggestions provided on the back of sports leaders to adapt and modify game each card when modifying the games and situations to be more inclusive of people activities or use the TREE model to develop with wide range of abilities. -

24 August Opening Ceremony

Paralympic Education Program Presented by Tracking the Tokyo 2020 Paralympic Games As you watch the Tokyo 2020 Paralympic Games, fill out the following information to help keep track of the amazing achievements of our Paralympians. 24 August Opening Ceremony Draw or write about your favourite moment from the Tokyo 2020 Paralympic Games Opening Ceremony. 25 August The team sports – Goalball, Wheelchair Basketball and Wheelchair Rugby started today! How did the Australian teams go? Goalball Australia vs Final score Wheelchair Basketball Australia vs Final score Wheelchair Rugby Australia vs Final score 26 August Who was Australia’s first medal winner? What colour medal did they win and for which event? Name Sport Event Place 1st 2nd 3rd 27 August Swimming is in full swing! Who are two athletes who have won medals for swimming? Name Event Place 1st 2nd 3rd Name It’s medal tally check Event time!! Place 1st 2nd 3rd 28 August Medal tally check! How many gold, silver and bronze medals has Australia won and what rank are they on the overall medal tally? Gold Silver Bronze Rank AUS 29 August Find out some information about one of the following sports and complete a sport profile: Boccia Table Tennis Shooting Rowing Sport name How many Australian athletes are competing in Tokyo? How many medals has Australia 1st 2nd 3rd won in this sport so far? What kinds of impairments do the athletes have in this sport? What is the name of one of the Australian athletes in this sport? When did they first compete for Australia? What is one achievement they have accomplished in their sporting career? 30 August Let’s check on our team sports! Goalball and Wheelchair Basketball are still competing. -

Disability Is the State Pupils May Find Themselves in When the Adjustments Needed to Overcome Their Impairments Don’T Happen

Supporting Secondary Pupils with Physical Disabilities in P.E Disability is the state pupils may find themselves in when the adjustments needed to overcome their impairments don’t happen. (extracted from Games All Children Can Play published by Scope) SEND 0-25 SERVICE Specialist Inclusion Support Service AS MY P.E TEACHER CAN YOU…? Ask me what I like to do in P.E, (in some cases this may mean- both before and after with regards to a medical procedure or an For further infor- mation accident and ask my parents too). please contact :- Don’t be afraid to ask me for ideas on how I can be included. Clare Hope or Jo Walker Always make me feel involved and do not leave me sat on the side -lines, feeling left out or excluded. Sensory and Physical Disabilities Team Try to include as many activities as possible i.e. sports that can be adapted, like basketball or table tennis so I am able to partici- Specialist Inclusion Support Service pate with other pupils. Do a normal P.E lesson, but always adapt it so I can take part. Do Elmwood Place it in such a way that it is not obvious and everyone in the class gets something out of it. 37 Burtons Way If you are doing a team sport or are working in a group make me a Birmingham captain. B36 0UG Be adventurous with your adaptations to an activity. As my P.E teacher, to talk to the school about what they can put in Telephone : 0121 704 6690 place to support me. -

OHSAA Handbook for Match Type)

2021-22 Handbook for Member Schools Grades 7 to 12 CONTENTS About the OHSAA ...............................................................................................................................................................................4 Who to Contact at the OHSAA ...........................................................................................................................................................5 OHSAA Board of Directors .................................................................................................................................................................6 OHSAA Staff .......................................................................................................................................................................................7 OHSAA Board of Directors, Staff and District Athletic Boards Listing .............................................................................................8 OHSAA Association Districts ...........................................................................................................................................................10 OHSAA Affiliated Associations ........................................................................................................................................................11 Coaches Associations’ Proposals Timelines ......................................................................................................................................11 2021-22 OHSAA Ready Reference -

SITTING VOLLEYBALL NATIONAL TEAMS 2020-2021 ATHLETE SELECTION PROCEDURES (Men and Women)

SITTING VOLLEYBALL NATIONAL TEAMS 2020-2021 ATHLETE SELECTION PROCEDURES (Men and Women) ELIGIBILITY FOR SITTING VOLLEYBALL NATIONAL TEAM In order to be eligible for selection to a National Team, all athletes must have a valid Canadian Passport as validation of Canadian Citizenship. Athletes must have a physical impairment that meets the classification standards for sitting volleyball as established by World ParaVolley (WPV). WPV is the international governing body for sitting volleyball. Athletes must meet the minimum eligibility requirements to participate in the Paralympic Games as set by the IPC, including having a confirmed classification status and be in good standing with WPV. Athletes must attend the Selection Camp* in order to be considered for selection to the National Team. An athlete who cannot attend the Selection Camp due to injury may be recommended for selection if he/she had previously been involved in the National Team. The athlete must receive the approval of the coaching staff and have written proof of medical reason for exclusion from the selection camp. Athletes must submit application for approval with medical note to the Para HP Manager or the High Performance Director - Sitting Volleyball prior to the Selection Camp. If an athlete’s injury does not prevent travel, it is expected that the athlete still attends selection camp and participates team off-court sessions. *With current COVID-19 restrictions, athletes will attend selection camp once it is safe to do so, all evaluations will be based on previous performance at camps and competitions SELECTION CRITERIA – NATIONAL TEAM MEMBER Athletes will be selected to a National Team program and rated within Volleyball Canada’s Gold Medal Profile (GMP) for Sitting Volleyball. -

An Investigation of Athletic Buoyancy in Adult Recreational and Sport Club Athletes

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School May 2020 An Investigation of Athletic Buoyancy in Adult Recreational and Sport Club Athletes Jackie Rae Victoriano Calhoun Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Kinesiology Commons, Other Psychology Commons, and the Sports Studies Commons Recommended Citation Calhoun, Jackie Rae Victoriano, "An Investigation of Athletic Buoyancy in Adult Recreational and Sport Club Athletes" (2020). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 5265. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/5265 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. AN INVESTIGATION OF ATHLETIC BUOYANCY IN ADULT RECREATIONAL AND SPORT CLUB ATHLETES A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The School of Kinesiology by Jackie V. Calhoun B.A., Louisiana State University, 2013 M.S., Louisiana State University, 2016 August 2020 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would first like to thank Dr. Alex Garn for your endless patience and thoughtful guidance. I am so thankful that you were willing to hear my interests and give me the opportunity to pursue them. I will forever be grateful for the time that you spent teaching me statistics and research methods, and for the support you provided me through my entire time as a graduate student. -

Should Video Gaming Be a School Sport? Video Gaming Has Pro Teams, Star Players, and Millions of Fans

DEBATE IT! We Write It, You Decide Should Video Gaming Be a School Sport? Video gaming has pro teams, star players, and millions of fans. But should it be considered a sport, like basketball or track? JANUARY 6, 2020 By Anna Starecheski & Kathy Wilmore Illustration by James Yamasaki Excitement builds as a huge crowd waits for the tournament to begin. The bleachers are filled with friends and family wearing school colors and holding signs. When the teams enter and take their places, the crowd goes wild, stomping their feet and shouting out the names of their favorite players. But this isn’t a varsity football or basketball game—and the players aren’t on a field or a court. They’re teams of students sitting in front of computer monitors, clicking mice and tapping away at keyboards. At a growing number of schools around the country, video gaming has become a varsity team sport. From 2018 to 2019, the number of schools participating in the High School Esports League grew from about 200 to more than 1,200. Video game competitions, known as esports (for electronic sports), are even bigger on the world stage. Nearly 100 million people around the globe watched the 2018 League of Legends World Championship finals. That’s about the same number of people as watched the 2018 Super Bowl. As esports have become more popular, some people are pushing for gaming to be considered a school sport. After all, they say, games like Fortnite, Counter-Strike: Global Offensive, and NBA 2K20 require skills and focus and can be intensely competitive. -

Sports N Spokes-July-2020.Pdf

The Magazine for Wheelchair Sports and Recreation Vol. 46 No. 4 July 2020 ADAPTIVE TRAINING Athletes modify workouts during pandemic MIND GAMES Adjusting to Paralympic postponement En Garde! The art of wheelchair fencing Inside SPORTS ’N SPOKES Features 16 Mental Shift Following the postponement of the 2020 Tokyo Paralympics until 2021 because of the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, some hopeful athletes have had to refocus. by Shelly Anderson 22 Parafencing Prowess Team USA Parafencers say there’s an art to the sport — which involves blades, instinct and timing. As they prepare for the Tokyo Paralympics, they want to get others involved, too. by Jonathan Gold 28 Staying Strong With the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic shutting sports events and gyms down across the country, some Paralympians found ways to adapt and still practice their training — albeit differently. by John Groth 28 on sportsnspokes.com Scan This! Digital Highlights Or go to JUNIOR ATHLETE OF THE YEAR WHEELCHAIR SOFTBALL TOURNEY sportsnspokes.com SPORTS ’N SPOKES will announce The Kansas City Royals Wheelchair Softball Club is hosting a its Junior Athlete of the Year wheelchair softball tournament July 11 at Pleasant Valley Park in award winner later this summer, Kansas City, Mo., and SPORTS ’N SPOKES will be there. Interested so visit the website to find out players can sign up at softball.registerKC.com. Check out our who received the honor. Facebook page and the website for photo and video coverage. July 2020 | SPORTS ’N SPOKES 3 Inside SPORTS ’N SPOKES 6 MY OPINION Digital Change by Tom Fjerstad 14 THE EXTRA POINT Making A Major Move by John Groth 33 PEOPLE You Can Still Be An Athlete by Bill Huber 16 36 OUTDOORS Working Outside The Box by Shelly Anderson Also in This Issue 8 In The Game 13 Spokes Stars 27 Sports Associations 38 On The Sidelines 41 Classifieds 41 ProShop 42 Final Frame 22 On the cover: Four-time SPORTS ’N SPOKES (ISSN 0161-6706). -

Coaching Manual Mark Walker

WHEELCHAIR BASKETBALL COACHING MANUAL MARK WALKER CONTENTS 1. Biography – Mark Walker .......................................... 1 2. Introduction .............................................................. 2 3. Coaching ................................................................... 3 Philosophy ................................................................ 3 The Pyramid of Success ............................................. 4 Coaching Styles ......................................................... 4 Communication ........................................................ 5 Discipline .................................................................. 5 Points of Emphasis/Don’t just run Drills .................... 5 Planning Effective Training Sessions .......................... 6 Basketball training Planning Sheet ............................ 7 Training for Peak Performance .................................. 8 Individual Players Evaluation .................................... 9 Final Thoughts .......................................................... 10 4. Classification of Athletes .......................................... 11 IWBF Guidelines ....................................................... 11-17 5. Equipment ............................................................... 18 Wheelchair Set Up ................................................... 18 Wheelchair set up and strapping by Tim Maloney .... 18 Common Sense Equipment ...................................... 19-20 6. Chair Skills .............................................................. -

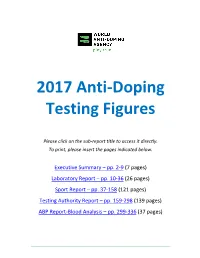

2017 Anti-Doping Testing Figures Report

2017 Anti‐Doping Testing Figures Please click on the sub‐report title to access it directly. To print, please insert the pages indicated below. Executive Summary – pp. 2‐9 (7 pages) Laboratory Report – pp. 10‐36 (26 pages) Sport Report – pp. 37‐158 (121 pages) Testing Authority Report – pp. 159‐298 (139 pages) ABP Report‐Blood Analysis – pp. 299‐336 (37 pages) ____________________________________________________________________________________ 2017 Anti‐Doping Testing Figures Executive Summary ____________________________________________________________________________________ 2017 Anti-Doping Testing Figures Samples Analyzed and Reported by Accredited Laboratories in ADAMS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This Executive Summary is intended to assist stakeholders in navigating the data outlined within the 2017 Anti -Doping Testing Figures Report (2017 Report) and to highlight overall trends. The 2017 Report summarizes the results of all the samples WADA-accredited laboratories analyzed and reported into WADA’s Anti-Doping Administration and Management System (ADAMS) in 2017. This is the third set of global testing results since the revised World Anti-Doping Code (Code) came into effect in January 2015. The 2017 Report – which includes this Executive Summary and sub-reports by Laboratory , Sport, Testing Authority (TA) and Athlete Biological Passport (ABP) Blood Analysis – includes in- and out-of-competition urine samples; blood and ABP blood data; and, the resulting Adverse Analytical Findings (AAFs) and Atypical Findings (ATFs). REPORT HIGHLIGHTS • A analyzed: 300,565 in 2016 to 322,050 in 2017. 7.1 % increase in the overall number of samples • A de crease in the number of AAFs: 1.60% in 2016 (4,822 AAFs from 300,565 samples) to 1.43% in 2017 (4,596 AAFs from 322,050 samples). -

Paralympic Sport Sacramento INDIVIDUAL

CITY OF SACRAMENTO, DEPARTMENT OF PARKS AND RECREATION ACCESS LEISURE, 4623 T Street, ste.B, SACRAMENTO, CA 95819 TELE: (916) 808-6017 FAX: (916) 840-7657 Paralympic Sport Sacramento INDIVIDUAL VOLUNTEER REGISTRATION "Play for Fun" Wheelchair Softball April 28, 2018 Please Type or Print Legibly Name _____________________________________________________________________________________ Mailing Address: _______________________________________________ City___________________ Zip__________ Phone: (Home) _________________ (Work) ________________ (Cell) _________________ (Fax) _________________ E-mail: ________________________________________________ (*Please respond to all emails!) Are you affiliated with a group for this volunteer activity? Yes __ No__. If YES, Group Name: __________________ Please mark which activity: ___ Goalball Season ___ Quad Rugby Season ___ Handcycling & Tandem Club Season ___Archery ___ Goalball Tournaments ___ Quad Rugby Tournaments ___ Wheelchair Basketball / Tournaments Are you a veteran with a disability? Yes ___ No ___ Are you currently on Active Duty? Yes ___ No ___ Branch of Service _________________________________ Is this your first time participating in Access Leisure/Paralympic Sport Sacramento programs? Yes ___ No ___ Have you had any experience with individuals with disabilities? If so, in what capacity? __________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________ Are you volunteering for class credit? YES___ NO ___ School of Attendance: ______________________________