CL181-Full-Issue.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Building Canadian National Identity Within the State and Through Ice Hockey: a Political Analysis of the Donation of the Stanley Cup, 1888-1893

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 12-9-2015 12:00 AM Building Canadian National Identity within the State and through Ice Hockey: A political analysis of the donation of the Stanley Cup, 1888-1893 Jordan Goldstein The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Robert K. Barney The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Kinesiology A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Jordan Goldstein 2015 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Intellectual History Commons, Political History Commons, Political Theory Commons, and the Sports Studies Commons Recommended Citation Goldstein, Jordan, "Building Canadian National Identity within the State and through Ice Hockey: A political analysis of the donation of the Stanley Cup, 1888-1893" (2015). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 3416. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/3416 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i Stanley’s Political Scaffold Building Canadian National Identity within the State and through Ice Hockey: A political analysis of the donation of the Stanley Cup, 1888-1893 By Jordan Goldstein Graduate Program in Kinesiology A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Jordan Goldstein 2015 ii Abstract The Stanley Cup elicits strong emotions related to Canadian national identity despite its association as a professional ice hockey trophy. -

Annual Report

KENNAN INSTITUTE Annual Report October 1, 2002–September 30, 2003 The Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars One Woodrow Wilson Plaza 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Washington, D.C. 20004-3027 www.wilsoncenter.org KENNAN INSTITUTE Kennan Institute Annual Report October 1, 2002–September 30, 2003 Kennan Institute Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars Kennan Moscow Project One Woodrow Wilson Plaza Galina Levina, Alumni Coordinator 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Ekaterina Alekseeva, Project Manager Washington,DC 20004-3027 Irina Petrova, Office Manager Pavel Korolev, Project Officer (Tel.) 202-691-4100;(Fax) 202-691-4247 www.wilsoncenter.org/kennan Kennan Kyiv Project Yaroslav Pylynskyj, Project Manager Kennan Institute Staff Nataliya Samozvanova, Office Manager Blair A. Ruble, Director Nancy Popson, Deputy Director Research Interns 2002-2003 Margaret Paxson, Senior Associate Anita Ackermann, Jeffrey Barnett, Joseph Bould, Jamey Burho, Bram F.Joseph Dresen, Program Associate Caplan, Sapna Desai, Cristen Duncan, Adam Fuss, Anton Ghosh, Jennifer Giglio, Program Associate Andrew Hay,Chris Hrabe, Olga Levitsky,Edward Marshall, Peter Atiq Sarwari, Program Associate Mattocks, Jamie Merriman, Janet Mikhlin, Curtis Murphy,Mikhail Muhitdin Ahunhodjaev, Financial Management Specialist Osipov,Anna Nikolaevsky,Elyssa Palmer, Irina Papkov, Mark Polyak, Edita Krunkaityte, Program Assistant Rachel Roseberry,Assel Rustemova, David Salvo, Scott Shrum, Erin Trouth, Program Assistant Gregory Shtraks, Maria Sonevytsky,Erin Trouth, Gianfranco Varona, Claudia Roberts, Secretary Kimberly Zenz,Viktor Zikas Also employed at the Kennan Institute during the 2002-03 In honor of the city’s 300th anniversary, all photographs in this report program year: were taken in St. Petersburg, Russia.The photographs were provided by Jodi Koehn-Pike, Program Associate William Craft Brumfield and Vladimir Semenov. -

List of NDT Personnel Currently Certified by Nrcan

List of NDT personnel currently certified by NRCan Last update = August 4, 2015 Welcome to the NRCan National Non-Destructive Testing (NDT) Certification Body’s Directory of NDT Personnel. Please Note - NRCan NDT CB makes all reasonable efforts to ensure candidate applications, examination requests and certification submissions are completed as per service standard targets. Despite these efforts, the occurrence of errors, omissions and delays cannot be completely ruled out and NRCan is not responsible for any direct and indirect costs, expenses or delays which may arise. Please note: All personnel appearing on the Certified Personnel list are currently certified even though they may not have received their updated certification card from NRCan. IT IS RECOMMENDED THAT EMPLOYERS AND CUSTOMERS VERIFY THE CLAIMED CERTIFICATIONS OF THEIR NDT PERSONNEL. Individuals and companies are encouraged to protect themselves from fraud and possible financial and legal entanglements by routinely checking the claimed certification status of individuals against this Internet list of NDT personnel currently certified by NRCan. • Do not accept a facsimile image of a wallet card as proof of certification; directly verify the faxed information against this web site listing. • In order to protect the reputation of CGSB/NRCan certification and to avoid potential legal or financial ramifications, you are requested to alert NRCan to any irregularities that you may perceive in the certification of individuals. This list of NDT personnel, currently certified by NRCan, was produced at NRCan and was accurate on the date shown. Any alteration of this information is strictly prohibited and may be unlawful. Any use of this information for purposes other than intended by NRCan may be unlawful and/or in violation of the Code of Conduct for NDT Personnel. -

Nietzsche's Beyond Good and Evil.Pdf

Leo Strauss Nietzsche’s Beyond Good and Evil A course offered in 1971–1972 St. John’s College, Annapolis, Maryland Edited and with an introduction by Mark Blitz With the assistance of Jay Michael Hoffpauir and Gayle McKeen With the generous support of Douglas Mayer Mark Blitz is Fletcher Jones Professor of Political Philosophy at Claremont McKenna College. He is author of several books on political philosophy, including Heidegger’s Being and Time and the Possibility of Political Philosophy (Cornell University Press, 1981) and Plato’s Political Philosophy (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010), and many articles, including “Nietzsche and Political Science: The Problem of Politics,” “Heidegger’s Nietzsche (Part I),” “Heidegger’s Nietzsche (Part II),” “Strauss’s Laws, Government Practice and the School of Strauss,” and “Leo Strauss’s Understanding of Modernity.” © 1976 Estate of Leo Strauss © 2014 Estate of Leo Strauss. All Rights Reserved Table of Contents Editor’s Introduction i–viii Note on the Leo Strauss Transcript Project ix–xi Editorial Headnote xi–xii Session 1: Introduction (Use and Abuse of History; Zarathustra) 1–19 Session 2: Beyond Good and Evil, Aphorisms 1–9 20–39 Session 3: BGE, Aphorisms 10–16 40–56 Session 4: BGE, Aphorisms 17–23 57–75 Session 5: BGE, Aphorisms 24–30 76–94 Session 6: BGE, Aphorisms 31–35 95–114 Session 7: BGE, Aphorisms 36–40 115–134 Session 8: BGE, Aphorisms 41–50 135–152 Session 9: BGE, Aphorisms 51–55 153–164 Session 10: BGE, Aphorisms 56–76 (and selections) 165–185 Session 11: BGE, Aphorisms 186–190 186–192 Session 12: BGE, Aphorisms 204–213 193–209 Session 13 (unrecorded) 210 Session 14: BGE, Aphorism 230; Zarathustra 211–222 Nietzsche, 1971–72 i Nietzsche’s Beyond Good and Evil Mark Blitz Leo Strauss offered this seminar on Nietzsche’s Beyond Good and Evil at St John’s College in Annapolis Maryland. -

Weather Images in Canadian Short Prose 1945-2000 Phd Dissertation

But a Few Acres of Snow? − Weather Images in Canadian Short Prose 1945-2000 PhD Dissertation Judit Nagy Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to express my sincere and heartfelt thanks to my advisor and director of the Modern English and American Literature, Dr. Aladár Sarbu for his professional support, valuable insights and informative courses, which all markedly prompted the completion of my dissertation. I would also thank Dr. Anna Jakabfi for her assistance with the Canadian content of the dissertation, the cornucopia of short stories she has provided me with, and for her painstaking endeavours to continually update the Canadian Studies section of the ELTE-SEAS library with books that were indispensable for my research. I am also grateful to Dr. Istán Géher, Dr. Géza Kállay, Dr. Péter Dávidházi and Dr. Judit Friedrich, whose courses inspired many of the ideas put forward in the second chapter of the dissertation (“Short Story Text and Weather Image”). I would also like to express my gratitude to the Central European Association of Canadian Studies for the conference grant that made it possible for me to deliver a presentation in the topic of my dissertation at the 2nd IASA Congress and Conference in Ottawa in 2005, to the Embassy of Canada in Hungary, especially Robert Hage, Pierre Guimond, Agnes Pust, Yvon Turcotte, Katalin Csoma and Enikő Lantos, for their on-going support, to the Royal Canadian Geographic Society and Environment Canada for providing me with materials and information regarding the geographical-climatological findings included in my dissertation, and, last but not least, to the chief organisers of the “Canada in the European Mind” series of conferences, Dr. -

Index to Volume 26 January to December 2016 Compiled by Patricia Coward

THE INTERNATIONAL FILM MAGAZINE Index to Volume 26 January to December 2016 Compiled by Patricia Coward How to use this Index The first number after a title refers to the issue month, and the second and subsequent numbers are the page references. Eg: 8:9, 32 (August, page 9 and page 32). THIS IS A SUPPLEMENT TO SIGHT & SOUND Index 2016_4.indd 1 14/12/2016 17:41 SUBJECT INDEX SUBJECT INDEX After the Storm (2016) 7:25 (magazine) 9:102 7:43; 10:47; 11:41 Orlando 6:112 effect on technological Film review titles are also Agace, Mel 1:15 American Film Institute (AFI) 3:53 Apologies 2:54 Ran 4:7; 6:94-5; 9:111 changes 8:38-43 included and are indicated by age and cinema American Friend, The 8:12 Appropriate Behaviour 1:55 Jacques Rivette 3:38, 39; 4:5, failure to cater for and represent (r) after the reference; growth in older viewers and American Gangster 11:31, 32 Aquarius (2016) 6:7; 7:18, Céline and Julie Go Boating diversity of in 2015 1:55 (b) after reference indicates their preferences 1:16 American Gigolo 4:104 20, 23; 10:13 1:103; 4:8, 56, 57; 5:52, missing older viewers, growth of and A a book review Agostini, Philippe 11:49 American Graffiti 7:53; 11:39 Arabian Nights triptych (2015) films of 1970s 3:94-5, Paris their preferences 1:16 Aguilar, Claire 2:16; 7:7 American Honey 6:7; 7:5, 18; 1:46, 49, 53, 54, 57; 3:5: nous appartient 4:56-7 viewing films in isolation, A Aguirre, Wrath of God 3:9 10:13, 23; 11:66(r) 5:70(r), 71(r); 6:58(r) Eric Rohmer 3:38, 39, 40, pleasure of 4:12; 6:111 Aaaaaaaah! 1:49, 53, 111 Agutter, Jenny 3:7 background -

Nimal Dunuhinga - Poems

Poetry Series nimal dunuhinga - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive nimal dunuhinga(19, April,1951) I was a Seafarer for 15 years, presently wife & myself are residing in the USA and seek a political asylum. I have two daughters, the eldest lives in Austalia and the youngest reside in Massachusettes with her husband and grand son Siluna.I am a free lance of all I must indebted to for opening the gates to this global stage of poets. Finally, I must thank them all, my beloved wife Manel, daughters Tharindu & Thilini, son-in-laws Kelum & Chinthaka, my loving brother Lalith who taught me to read & write and lot of things about the fading the loved ones supply me ingredients to enrich this life's bitter-cake.I am not a scholar, just a sailor, but I learned few things from the last I found Man is not belongs to anybody, any race or to any religion, an independant-nondescript heaviest burden who carries is the Brain. Conclusion, I guess most of my poems, the concepts based on the essence of Buddhist personal belief is the Buddha who was the greatest poet on this planet earth.I always grateful and admire him. My humble regards to all the readers. www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive 1 * I Was Born By The River My scholar friend keeps his late Grandma's diary And a certain page was highlighted in the color of yellow. My old ferryman you never realized that how I deeply loved you? Since in the cradle the word 'depth' I heard several occasions from my parents. -

Core 1..146 Hansard (PRISM::Advent3b2 8.00)

CANADA House of Commons Debates VOLUME 140 Ï NUMBER 098 Ï 1st SESSION Ï 38th PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Friday, May 13, 2005 Speaker: The Honourable Peter Milliken CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) All parliamentary publications are available on the ``Parliamentary Internet Parlementaire´´ at the following address: http://www.parl.gc.ca 5957 HOUSE OF COMMONS Friday, May 13, 2005 The House met at 10 a.m. Parliament on February 23, 2005, and Bill C-48, an act to authorize the Minister of Finance to make certain payments, shall be disposed of as follows: 1. Any division thereon requested before the expiry of the time for consideration of Government Orders on Thursday, May 19, 2005, shall be deferred to that time; Prayers 2. At the expiry of the time for consideration of Government Orders on Thursday, May 19, 2005, all questions necessary for the disposal of the second reading stage of (1) Bill C-43 and (2) Bill C-48 shall be put and decided forthwith and successively, Ï (1000) without further debate, amendment or deferral. [English] Ï (1010) MESSAGE FROM THE SENATE The Speaker: Does the hon. government House leader have the The Speaker: I have the honour to inform the House that a unanimous consent of the House for this motion? message has been received from the Senate informing this House Some hon. members: Agreed. that the Senate has passed certain bills, to which the concurrence of this House is desired. Some hon. members: No. Mr. Jay Hill (Prince George—Peace River, CPC): Mr. -

Map of Canada, Official Results of the 38Th General Election – PDF Format

2 5 3 2 a CANDIDATES ELECTED / CANDIDATS ÉLUS Se 6 ln ln A nco co C Li in R L E ELECTORAL DISTRICT PARTY ELECTED CANDIDATE ELECTED de ELECTORAL DISTRICT PARTY ELECTED CANDIDATE ELECTED C er O T S M CIRCONSCRIPTION PARTI ÉLU CANDIDAT ÉLU C I bia C D um CIRCONSCRIPTION PARTI ÉLU CANDIDAT ÉLU É ol C A O N C t C A H Aler 35050 Mississauga South / Mississauga-Sud Paul John Mark Szabo N E !( e A N L T 35051 Mississauga--Streetsville Wajid Khan A S E 38th GENERAL ELECTION R B 38 ÉLECTION GÉNÉRALE C I NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR 35052 Nepean--Carleton Pierre Poilievre T A I S Q Phillip TERRE-NEUVE-ET-LABRADOR 35053 Newmarket--Aurora Belinda Stronach U H I s In June 28, 2004 E T L 28 juin, 2004 É 35054 Niagara Falls Hon. / L'hon. Rob Nicholson E - 10001 Avalon Hon. / L'hon. R. John Efford B E 35055 Niagara West--Glanbrook Dean Allison A N 10002 Bonavista--Exploits Scott Simms I Z Niagara-Ouest--Glanbrook E I L R N D 10003 Humber--St. Barbe--Baie Verte Hon. / L'hon. Gerry Byrne a 35056 Nickel Belt Raymond Bonin E A n L N 10004 Labrador Lawrence David O'Brien s 35057 Nipissing--Timiskaming Anthony Rota e N E l n e S A o d E 10005 Random--Burin--St. George's Bill Matthews E n u F D P n d ely E n Gre 35058 Northumberland--Quinte West Paul Macklin e t a s L S i U a R h A E XEL e RÉSULTATS OFFICIELS 10006 St. -

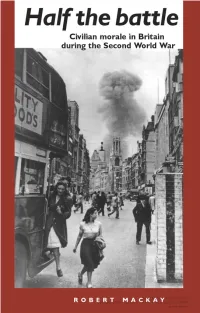

Robert Mackay - 9781526137425 Downloaded from Manchesterhive.Com at 09/24/2021 07:30:30PM Via Free Access HALF the BATTLE

Robert Mackay - 9781526137425 Downloaded from manchesterhive.com at 09/24/2021 07:30:30PM via free access HALF THE BATTLE Robert Mackay - 9781526137425 Downloaded from manchesterhive.com at 09/24/2021 07:30:30PM via free access prelim.p65 1 16/09/02, 09:21 Robert Mackay - 9781526137425 Downloaded from manchesterhive.com at 09/24/2021 07:30:30PM via free access prelim.p65 2 16/09/02, 09:21 HALF THE BATTLE Civilian morale in Britain during the Second World War ROBERT MACKAY Manchester University Press Manchester and New York distributed exclusively in the USA by Palgrave Robert Mackay - 9781526137425 Downloaded from manchesterhive.com at 09/24/2021 07:30:30PM via free access prelim.p65 3 16/09/02, 09:21 Copyright © Robert Mackay 2002 The right of Robert Mackay to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Published by Manchester University Press Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9NR, UK and Room 400, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk Distributed exclusively in the USA by Palgrave, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA Distributed exclusively in Canada by UBC Press, University of British Columbia, 2029 West Mall, Vancouver, BC, Canada V6T 1Z2 British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data applied for ISBN 0 7190 5893 7 hardback 0 7190 5894 5 paperback First published 2002 10 09 08 07 06 05 04 03 02 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Typeset by Freelance Publishing Services, Brinscall, Lancs. -

The Song of the Prairie Land 101 Pauline Johnson

CONTENTS PAGE A TOAST TO BEAUTY 17 PRELUDE 18 TIrE CRY OF THE SONG CHILDREN 20 A SONG TO CANADA 24 A POET STOOD FORLORN 27 SONG OF THE SNOWSHOE TRAMP 34 ADVERSITY. 40 WHOM SHALL MY HEART CONDEMN? • 42 FIRST SONG WITHOUT A NAME 49 THE WHIP-POOR-WILL 51 TRAPPER ONE AND TRAPPER Two; OR, THE GHOST OF UNGAVA. 57 REED SONGS 69 A SONG OF BROTHERHOOD 74 BARBARY 78 To THE UNCROWNED KINGS 80 I FEEL NOR UNDERSTAND 83 AT THE PIANO 85 THE WAKING THOUGHT 87 OTUS AND RISMEL (A BALLADE OF THE LONG SEA LANES) PAG! THE SONG OF THE PRAIRIE LAND 101 PAULINE JOHNSON. 107 THE HAUNT OF A LoST LoVE. 108 AT THE FORD • 109 THE ROSE AND THE WILDFLOWER 112 SECOND SONG WITHOUT A NAME 116 BRITISH COLUMBIA. 117 A SONG TO THE SINGERS. 119 ALONE 120 A SONG OF BETTER UNDERSTANDING 121 THE MONGREL. 126 WHIST-WHEE 132 THIRD SONG WITHOUT A NAME. 134 THE CONVICT MARCH. 135 MARY MAHONE. 137 SAINT ELIAS 141 AT BROOKSIDE MANOR. 144 SOMEWHERE, SOMETIME THE GLORY. 146 FRANCE • 148 GIFTS 149 By HOWE SOUND 150 PEACE 152 6 Prelude PRELUDE wo jugs upon a table stood; 1 am Caneo; T One ample of girth and sweet of cavern, And my skin is brown from the comrade sun. But a shapeless bit of homely wood And my heart is a cluster of grapes; each one That .you would scorn in the poorest tavern; I ip and ready to flow together The other traced and interlaced In the channel sweet of a purple song. -

Swedish Film Magazine #1 2008

SWEDISH FILM NO.1/08 BERLIN PREMIERES:HEAVEN’S HEART LEO CIAO BELLA SPENDING THE NIGHT TOMMY MY UNCLE LOVED THE COLOUR YELLOW www.swedishfi lm.orgXX XX XX SWEDISH FILM NO. 1 2008 FOREWORD A NEW SPRING FOR SWEDISH FILM Director International Pia Lundberg On one of last summer’s sunniest days we received the news that Ingmar Bergman Department Phone +46 70 692 79 80 pia.lundberg@sfi .se had passed away at his home on Fårö at the age of 89. The stream of condolences that Festivals, features Gunnar Almér poured in from all over the world reminded us Swedes just how great Bergman truly was. Im- Phone +46 70 640 46 56 gunnar.almer@sfi .se mediately the question was being asked as to who would inherit Bergman’s mantle. The answer Features, special Petter Mattsson projects Phone +46 70 607 11 34 is nobody. Or lots of people. Because in the new Swedish fi lms that are emerging, one can de- petter.mattsson@sfi .se tect a strong measure of personal expression and the re-emergence of the auteur tradition. Festivals, Sara Yamashita Rüster documentaries Phone +46 76 117 26 78 An impressive year of Swedish fi lms awaits us. Many of our most successful, award- sara.ruster@sfi .se winning and internationally-acclaimed directors will be presenting new fi lms this year. They Festivals, short fi lms Andreas Fock Phone +46 70 519 59 66 include Lukas Moodysson (Show Me Love, Together, Lilya 4-ever) whose fi rst major interna- andreas.fock@sfi .se tional collaboration, Mammoth, will star Gael Garcia Bernal and Michelle Williams in the Press Offi cer Jan Göransson Phone +46 70 603 03 62 leading roles.