No Child Left Behind and Its Communication Effectiveness in Diverse Communities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Jersey State Plan Draft Proposed February 15, 2017

Every Student Succeeds Act New Jersey State Plan Draft Proposed February 15, 2017 New Jersey DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Table of Contents From the Commissioner ............................................................................................. 3 Introduction ................................................................................................................ 4 Section 1: Long-term Goals ....................................................................................... 8 Section 2: Consultation and Performance Management ..........................................18 2.1 Consultation ................................................................................................................... 18 2.2 System of Performance Management ............................................................................ 24 Section 3: Academic Assessments ...........................................................................36 Section 4: Accountability, Support, and Improvement for Schools ........................40 4.1 Accountability Systems ................................................................................................. 42 4.2 Identification of Schools ................................................................................................ 68 4.3 State Support and Improvement for Low-performing Schools...................................... 72 Section 5: Supporting Excellent Educators .............................................................79 5.1 Educator Development, Retention and Advancement -

Year-Round Program

2 2019 NSPRA Mark of Distinction Submission INTRODUCTION On behalf of the New Jersey School Public Relations Association, I respectfully request your consideration of this entry for a Mark of Distinction award in the category of Professional Development/PR Skill Building. NJSPRA elected officers and members have worked diligently over the last three to five years to provide the most relevant professional development for our members and to attract new members by doing so. A FRESH LOOK In 2015, membership was flat and attendance at workshops was averaging 20 people, at most. We decided to embark upon a rebranding and subsequent website relaunch (www.njspra.com) in 2016. This allowed us to display a visual identity that matched the high-quality professional development and support that we were providing. (Screen shot of homepage is attached.) In working with a professional graphic designer, we developed the logo below which includes the chapter name with an abstract graphic. New Logo launched in 2016: 3 Website Redesign: 4 MEMBERSHIP Over the last three years, we have continued to see a steady increase in membership. In fact, we’ve grown nearly 125% in just the last two years alone! (Membership lists for 2016 through the current year are below.) The growth didn’t come easily. We believe it’s a result of the combined efforts of branding, targeted outreach, school communication awards program and collaboration with other professional associations. For NJSPRA, membership has been a struggle since the early 2000s. At that time New Jersey enacted fiscal accountability regulations that limit how much time a public school employee can spend on traditional public relations. -

New Jersey Districts Using Teachscape Tools Contact Evan Erdberg, Director of North East Sales, for More Information. Email

New Jersey Districts using Teachscape Tools Contact Evan Erdberg, Director of North East Sales, for more information. Email: [email protected] Mobile: 646.260.6931 ATLANTIC Atlantic County Institute of Technology Egg Harbor City Public School District Galloway Township Public Schools Mullica Township School District Richard Stockton College BERGEN Alpine School District Bergen County Special Services School District Bergen County Technical School District Bergenfield Public Schools Carlstadt East Rutherford Regional School District Carlstadt School District Cresskill School District Emerson School District Englewood Cliffs Public Schools Fort Lee Public Schools Glen Rock School District Hasbrouck Heights School District Leonia School District Maywood School District Midland Park School District New Milford School District Sage Day Schools South Bergen Jointure Commission Teaneck School District Tenafly Public Schools Wallington Public Schools Wood Ridge School District BURLINGTON Bass River Township School District Beverly City School District Bordentown Regional School District Delanco Township School District Delran Township School District Edgewater Park Township School District Evesham Township School District Mansfield Township School District Medford Lakes School District Palmyra Public Schools Pemberton Township School District Riverton School District Southampton Township Schools Springfield Township School District Tabernacle School District CAMDEN Camden Diocese Lindenwold School District Voorhees Township School District -

2010-11 MAIT Director's Report

2010-11 MAIT Director’s Report Goals from Academic Year 2010-11 [Use this space to describe any goals your program set and to report results your program measured.] The Master of Arts in Instructional Technology (MAIT) Program faculty worked toward three major goals during the past year. First, we endeavored to continue partnerships with existing cohort groups and establish new partnerships. Secondly, we started to implement the Instructional Technology Leadership Academy (ITLA), and a minor program in Digital Literacy and Multimedia Design that we had developed during the 2009-2010 academic year. Finally, we successfully conducted a five-year program review. During 2010-2011 including Summer 2011, we offered a total of seven different off- campus programs. Eight Burlington cohort group students successfully finished the MAIT program in Fall 2010. Students in Brigantine, Linwood, Camden County Technical School (CCTS), and Millville III continued taking courses. Beginning in Spring 2011, the Southern Regional School District (SRSD) started a new cohort with 16 students. During the Summer 2011, we were able to offer an off-campus MAIT (non-cohort) course at Hammonton High School, and hope to continue offering off-campus courses at Hammonton High. During the Spring 2011, in conjunction with the ITLA, we launched INTC 4610: Advanced Instructional Technology I (2 crs.) with 19 selected pre-service teachers, and each student was placed in a school with a tech-savvy mentor. These students will continue to take INTC 4620: Advanced Instructional Technology II (2 crs.) in the Fall 2011 to advance their leadership and technology skills in K-12 schools. -

Updated NJ Rankings.Xlsx

New Jersey School Relative Efficiency Rankings ‐ Outcome = Student Growth 2012, 2013, 2014 (deviations from other schools in same county, controlling for staffing expenditure per pupil, economies of scale, grade range & student populations) 3 Year Panel Separate Yearly Model (Time Models (5yr Avg. Varying School School District School Grade Span Characteristics) Ranking 1 Characteristics) Ranking 2 ESSEX FELLS SCHOOL DISTRICT Essex Fells Elementary School PK‐06 2.92 23.44 1 Upper Township Upper Township Elementary School 03‐05 3.00 12.94 2 Millburn Township Schools Glenwood School KG‐05 2.19 62.69 3 Hopewell Valley Regional School District Toll Gate Grammar School KG‐05 2.09 10 2.66 4 Verona Public Schools Brookdale Avenue School KG‐04 2.33 42.66 5 Parsippany‐Troy Hills Township Schools Northvail Elementary School KG‐05 2.35 32.56 6 Fort Lee Public Schools School No. 1PK‐06 2.03 12 2.50 7 Ridgewood Public Schools Orchard Elementary School KG‐05 1.88 17 2.43 8 Discovery Charter School DISCOVERY CS 04‐08 0.89 213 2.42 9 Princeton Public Schools Community Park School KG‐05 1.70 32 2.35 10 Hopewell Valley Regional School District Hopewell Elementary School PK‐05 1.65 37 2.35 11 Cresskill Public School District Merritt Memorial PK‐05 1.69 33 2.33 12 West Orange Public Schools REDWOOD ELEMENTARY SCHOOL KG‐05 1.81 21 2.28 13 Millburn Township Schools South Mountain School PK‐05 1.93 14 2.25 14 THE NEWARK PUBLIC SCHOOLS ELLIOTT STREET ELEMENTARY SCHOOL PK‐04 2.15 82.25 15 PATERSON PUBLIC SCHOOLS SCHOOL 19 KG‐04 1.95 13 2.24 16 GALLOWAY TOWNSHIP -

New Jersey Consortia for Excellence Through Equity-South

NEW JERSEY CONSORTIA FOR EXCELLENCE THROUGH EQUITY-SOUTH 2018-19 SCHEDULE OF ACTIVITIES In 2017 the Penn Center for Educational Leadership in the Graduate School of Education at the University of Pennsylvania collaborated with the New Jersey Association of School Administrators, NJASA, to continue to develop an evolving regional consortium of school districts in Southern New Jersey that are committed to work together to support and nurture the school success of ALL of their students. The New Jersey Consortia for Excellence Through Equity- in the South, Central and North- are driven by a mission to positively transform the lives of each and every one of their students by preparing them for success in post-secondary education and in life – especially the diverse children and youth who may have traditionally struggled academically in their systems, or who might likely be the first in their family to attend and graduate from college. We are partners and a strong collective voice who can help gather the resources, thought and energy needed to create and sustain meaningful educational change to the benefit each and every one of the children we serve locally and state-wide. The Consortia serve as valuable resources where the best of what we know of research and informed practice percolate- ideas and strategies that help district leaders effectively address their critical local challenges of securing and sustaining high level student achievement for and ultimately equity in attainment and life success for all students. Gerri Carrol, Consortium Co-Director Dr. Robert L. Jarvis 609-685-0476 Director Equity Leadership Initiatives [email protected] Catalyst@Penn GSE University of Pennsylvania 3440 Market Street Room 560-60 Philadelphia, PA 19104-3325 215.746.7375 or 215.990.5788 [email protected] Dr. -

The New Jersey Department of Education

The New Jersey Department of Education Representatives from the following organizations have engaged in conversations with the NJDOE about New Jersey’s ESSA State Plan and related policies: Abbott Leadership Institute Diocese of Trenton NJ Association for the Education of NJ Parent Teacher Association Advocates for Children of NJ (ACNJ) Education Law Center Young Children (NJPTA) Aging Out Project Educational Services Commission NJ Association of Colleges for NJ Principals and Supervisors Agudath Israel of America NJ Office of NJ Teacher Education Association (NJPSA) AIM Institute for Learning and Essex County Juvenile Detention NJ Association of Federal Program NJ School Age Care Coalition Research Center Administrators (NJAFPA) NJ School Boards Association Alliance for Newark Public Schools Essex County Local Education NJ Association of Independent (NJSBA) American Federation of Teachers – Agency Schools NJ School-Age Care Coalition (NJ NJ Chapter Foreign Language Educators of NJ NJ Association of School SACC) American Heart Association Garden State Coalition of Schools Psychologists (NJASP) NJ Special Parent Advocacy Group ARC of NJ Great Schools NJ NJ Association of State Colleges NJ State Board of Education Archway Programs Guttenburg and Universities (NJASCU) NJ State School Nurses Association Association of Independent Junior Achievement of NJ NJ Association of Student Councils (NJSSNA) Colleges and Universities in NJ Junior League NJ Association of Supervision and NJ Statewide Parent Advocacy Association of Language Arts Juvenile -

Every Student Succeeds Act New Jersey State Plan Draft

Every Student Succeeds Act New Jersey State Plan Draft Proposed February 15, 2017 New Jersey DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Table of Contents From the Commissioner .............................................................................................3 Introduction ................................................................................................................4 Section 1: Long-term Goals .......................................................................................8 Section 2: Consultation and Performance Management ..........................................18 2.1 Consultation ................................................................................................................... 18 2.2 System of Performance Management ............................................................................ 24 Section 3: Academic Assessments ...........................................................................36 Section 4: Accountability, Support, and Improvement for Schools ........................40 4.1 Accountability Systems ................................................................................................. 42 4.2 Identification of Schools ................................................................................................ 68 4.3 State Support and Improvement for Low-performing Schools...................................... 72 Section 5: Supporting Excellent Educators .............................................................79 5.1 Educator Development, Retention and Advancement -

New Jesey Network Tyo Close the Achievement Gaps

NEW JERSEY CONSORTIA FOR EXCELLENCE THROUGH EQUITY-SOUTH 2019-20 SCHEDULE OF ACTIVITIES In 2017 the Penn Center for Educational Leadership in the Graduate School of Education at the University of Pennsylvania collaborated with the New Jersey Association of School Administrators, NJASA, to continue to develop an evolving regional consortium of school districts in Central New Jersey that are committed to work together to support and nurture the school and life success of ALL of their students. The New Jersey Consortia for Excellence Through Equity in the South, Central and North are driven by a mission to positively transform the lives of each and every one of their students by preparing them for success in post-secondary education and in life – especially the diverse children and youth who may have traditionally struggled academically in their systems, or who might likely be the first in their family to attend and graduate from college. We are partners and a strong collective voice who can help gather the resources, thought and energy needed to create and sustain meaningful educational change to the benefit each and every of the children we serve locally and state-wide. The Consortia serve as valuable resources where the best of what we know of research and informed practice percolate- ideas and strategies that help district leaders effectively address their critical local challenges of securing and sustaining high level student achievement and ultimately equity in attainment and life success for all students. Gerri Carroll, Co-Director Dr. Robert L. Jarvis 909.685.0476 Director of the Penn Coalition for Educational Equity [email protected] Catalyst @Penn GSE University of Pennsylvania 3440 Market Street Room 560-30 Philadelphia, PA 19104-3325 215.746.7375 or 215.990.5788 [email protected] Dr. -

Appendix V Date Issued: 5/2015

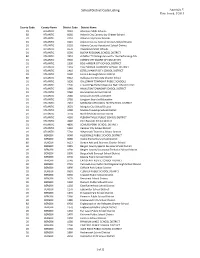

School District Code Listing Appendix V Date Issued: 5/2015 County Code County Name District Code District Name 01 ATLANTIC 0010 Absecon Public Schools 80 ATLANTIC 6060 Atlantic City Community Charter School 01 ATLANTIC 0110 Atlantic City Public Schools 01 ATLANTIC 0125 Atlantic County Special Services School District 01 ATLANTIC 0120 Atlantic County Vocational School District 01 ATLANTIC 0570 Brigantine Public Schools 01 ATLANTIC 0590 BUENA REGIONAL SCHOOL DISTRICT 80 ATLANTIC 7410 chARTer~TECH High School for the Performing Arts 01 ATLANTIC 0960 CORBIN CITY BOARD OF EDUCATION 01 ATLANTIC 1300 EGG HARBOR CITY SCHOOL DISTRICT 01 ATLANTIC 1310 EGG HARBOR TOWNSHIP SCHOOL DISTRICT 01 ATLANTIC 1410 ESTELL MANOR CITY SCHOOL DISTRICT 01 ATLANTIC 1540 Folsom Borough School District 80 ATLANTIC 6612 Galloway Community Charter School 01 ATLANTIC 1690 GALLOWAY TOWNSHIP PUBLIC SCHOOLS 01 ATLANTIC 1790 Greater Egg Harbor Regional High School District 01 ATLANTIC 1940 HAMILTON TOWNSHIP SCHOOL DISTRICT 01 ATLANTIC 1960 Hammonton School District 01 ATLANTIC 2680 Linwood City School District 01 ATLANTIC 2780 Longport Board of Education 01 ATLANTIC 2910 MAINLAND REGIONAL HIGH SCHOOL DISTRICT 01 ATLANTIC 3020 Margate City School District 01 ATLANTIC 3480 Mullica Township School District 01 ATLANTIC 3720 Northfield City School District 01 ATLANTIC 4180 PLEASANTVILLE PUBLIC SCHOOL DISTRICT 01 ATLANTIC 4240 Port Republic School District 01 ATLANTIC 4800 SOMERS POINT SCHOOL DISTRICT 01 ATLANTIC 5350 Ventnor City School District 01 ATLANTIC 5760 Weymouth Township -

Appendix B DEFENDANTS SCHOOL DISTRICTS in the UNITED STATES

Case 1:20-cv-05878-CM Document 1-1 Filed 07/28/20 Page 1 of 119 Appendix B DEFENDANTS SCHOOL DISTRICTS IN THE UNITED STATES (Abbreviations: S.D. = School District, I.S.D. = Independent School District, Unified School District = U.S.D., Consolidated School District = C.S.D., Elementary School District = E.S.D., School District = S.D.) Alabama Alabaster City Enterprise City Montgomery County Albertville City Escambia County Morgan County Alexander City Etowah County Mountain Brook City Andalusia City Eufaula City Muscle Shoals City Anniston City Fairfield City Oneonta City Arab City Fayette County Opelika City Attalla City Florence City Opp City Athens City Fort Payne City Oxford City Auburn City Fort Rucker Ozark City Autauga County Franklin County Pelham City Schools Baldwin County Gadsden City Pell City Barbour County Geneva City Perry County Bessemer City Geneva County Phenix City Bibb County Greene County Pickens County Birmingham City Guntersville City Piedmont City Blount County Hale County Pike County Boaz City Haleyville City Randolph County Brewton City Hartselle City Roanoke City Bullock County Henry County Russell County Butler County Homewood City Russellville City Calhoun County Hoover City Saint Clair County Chambers County Houston County Saraland Cherokee County Huntsville City Scottsboro City Chilton County Jackson County Selma City Choctaw County Jacksonville City Sheffield City Clarke County Jasper City Shelby County Clay County Jefferson County Sumter County Cleburne County Lamar County Sylacauga City Coffee County Lanett -

A Study of Overrepresentation of Minorities in Special Education in Southern New Jersey Public Schools

Rowan University Rowan Digital Works Theses and Dissertations 5-19-2004 A study of overrepresentation of minorities in special education in southern New Jersey public schools Carol Phister Rowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://rdw.rowan.edu/etd Part of the Special Education and Teaching Commons Recommended Citation Phister, Carol, "A study of overrepresentation of minorities in special education in southern New Jersey public schools" (2004). Theses and Dissertations. 1213. https://rdw.rowan.edu/etd/1213 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Rowan Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Rowan Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A STUDY OF OVERREPRESENTATION OF MINORORITIES IN SPECIAL EDUCATION IN SOUTHERN NEW JERSEY PUBLIC SCHOOLS By Carol Phister A Thesis Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts Degree of The Graduate School at Rowan University May 18, 2004 Approved by Date Approved 4//// ABSTRACT Carol Phister A STUDY OF OVERREPRESENTATION OF MINORORITIES IN SPECIAL EDUCATION IN SOUTHERN NEW JERSEY PUBLIC SCHOOLS 2003/04 Dr. Steven Crites Master of Arts in Special Education The purpose of this study was to determine if there is an overrepresentation of minority students in special education in southern New Jersey Public Schools. Data was disaggregated to the district level for 25 randomly chosen public school districts in southern New Jersey. Data were reported on the total school population and the total number of students classified as eligible for special education.