Feminism and Video: a View from the Village Joan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heretics Proposal.Pdf

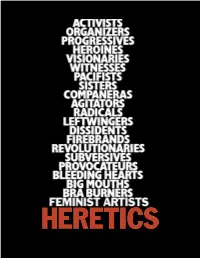

A New Feature Film Directed by Joan Braderman Produced by Crescent Diamond OVERVIEW ry in the first person because, in 1975, when we started meeting, I was one of 21 women who THE HERETICS is a feature-length experimental founded it. We did worldwide outreach through documentary film about the Women’s Art Move- the developing channels of the Women’s Move- ment of the 70’s in the USA, specifically, at the ment, commissioning new art and writing by center of the art world at that time, New York women from Chile to Australia. City. We began production in August of 2006 and expect to finish shooting by the end of June One of the three youngest women in the earliest 2007. The finish date is projected for June incarnation of the HERESIES collective, I remem- 2008. ber the tremendous admiration I had for these accomplished women who gathered every week The Women’s Movement is one of the largest in each others’ lofts and apartments. While the political movement in US history. Why then, founding collective oversaw the journal’s mis- are there still so few strong independent films sion and sustained it financially, a series of rela- about the many specific ways it worked? Why tively autonomous collectives of women created are there so few movies of what the world felt every aspect of each individual themed issue. As like to feminists when the Movement was going a result, hundreds of women were part of the strong? In order to represent both that history HERESIES project. We all learned how to do lay- and that charged emotional experience, we out, paste-ups and mechanicals, assembling the are making a film that will focus on one group magazines on the floors and walls of members’ in one segment of the larger living spaces. -

216631157.Pdf

The Alternative Media Handbook ‘Alternative media’ are media produced by the socially, culturally and politically e xcluded: they are always independently run and often community-focused, ranging from pirate radio to activist publications, from digital video experiments to ra dical work on the Web. The Alternative Media Handbook explores the many and dive rse media forms that these non-mainstream media take. The Alternative Media Hand book gives brief histories of alternative radio, video and lm, press and activity on the Web, then offers an overview of global alternative media work through nu merous case studies, before moving on to provide practical information about alt ernative media production and how to get involved in it. The Alternative Media H andbook includes both theoretical and practical approaches and information, incl uding sections on: • • • • • • • • successful fundraising podcasting blogging publishing pitch g a project radio production culture jamming access to broadcasting. Kate Coyer is an independent radio producer, media activist and post-doctoral re search fellow with the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of P ennsylvania and Central European University in Budapest. Tony Dowmunt has been i nvolved in alternative video and television production since 1975 and is now cou rse tutor on the MA in Screen Documentary at Goldsmiths, University of London. A lan Fountain is currently Chief Executive of European Audiovisual Entrepreneurs (EAVE), a professional development programme for lm and television producers. He was the rst Commissioning Editor for Independent Film and TV at Channel Four, 198 1–94. Media Practice Edited by James Curran, Goldsmiths, University of London The Media Practice hand books are comprehensive resource books for students of media and journalism, and for anyone planning a career as a media professional. -

Artist Writings: Critical Essays, Reception, and Conditions of Production Since the 60S

Artist Writings: Critical Essays, Reception, and Conditions of Production since the 60s by Leanne Katherine Carroll A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy—History of Art Department of Art University of Toronto © Copyright by Leanne Katherine Carroll 2013 Artist Writings: Critical Essays, Reception, and Conditions of Production since the 60s Leanne Carroll Doctor of Philosophy—History of Art Department of Art University of Toronto 2013 Abstract This dissertation uncovers the history of what is today generally accepted in the art world, that artists are also artist-writers. I analyse a shift from writing by artists as an ostensible aberration to artist writing as practice. My structuring methodology is assessing artist writings and their conditions and reception in their moment of production and in their singularity. In Part 1, I argue that, while the Abstract-Expressionist artist-writers were negatively received, a number of AbEx- inflected conditions influenced and made manifest the valuing of artist writings. I demonstrate that Donald Judd conceived of writing as stemming from the same methods and responsibilities of the artist—following the guiding principle that art comes from art, from taking into account developments of the recent past—and as an essayistic means to argumentatively air his extra-art concerns; that writing for Dan Graham was an art world right of entry; and that Robert Smithson treated words as primary substances in a way that complicates meaning in his articles and in his objects and earthworks, in the process introducing a modernist truth to materials that gave the writing cachet while also serving as the basis for its domestication. -

Innovators, Disruptors, & Entrepreneurs

WEBBMAGAZINE Summer 2012 Innovators, Disruptors, & Entrepreneurs Webb Alumni Shaping the 21st Century Those ideas form the crux of Holland’s past and current work, time behind the camera. “It’s always a balancing act,” she says, and it’s what has pushed him to change the status quo. between the creative impulse and business practicalities. At UX-FLO, he currently is working for a client, Maxon, that “The path, particularly for documentary filmmakers, is coming makes 3D animation software called Cinema 4D. up with an idea and seeing if there’s a market for it.” Even within design, Holland points out that a multifaceted background is more important than ever for career success —specifically, software programming skills and design talent. “This type of multidisciplinary person is incredibly valuable to corporations, because so few of them exist,” he points out. It’s those people—people who can bring diverse skills, abilities and interests to their careers—who are redefining the paradigm for career and personal success. It’s a new paradigm, but it’s based on an old concept: the concept of the well-rounded individual, a concept that The Webb Schools have been instilling in their students since 1922. “We are always trying to push the boundaries while paradoxically maintaining a sense of balance. We believe that present and future paradigms are a balance of appropriate crafting of progressive ideas, and sometimes that means maintaining conservative traditions. We really just try to pay attention to what will hold real value—this is the key. If we can do this, we will create timeless value in the marketplace, and this type of design will never go out of style.” Spanning decades, Holland’s career blends entrepreneurship, 6 innovation and disruption. -

Women's Experimental Cinema

FILM STUDIES/WOMEN’S STUDIES BLAETZ, Women’s Experimental Cinema provides lively introductions to the work of fifteen avant- ROBIN BLAETZ, garde women filmmakers, some of whom worked as early as the 1950s and many of whom editor editor are still working today. In each essay in this collection, a leading film scholar considers a single filmmaker, supplying biographical information, analyzing various influences on her Experimental Cinema Women’s work, examining the development of her corpus, and interpreting a significant number of individual films. The essays rescue the work of critically neglected but influential women filmmakers for teaching, further study, and, hopefully, restoration and preservation. Just as importantly, they enrich the understanding of feminism in cinema and expand the ter- rain of film history, particularly the history of the American avant-garde. The essays highlight the diversity in these filmmakers’ forms and methods, covering topics such as how Marie Menken used film as a way to rethink the transition from ab- stract expressionism to Pop Art in the 1950s and 1960s, how Barbara Rubin both objecti- fied the body and investigated the filmic apparatus that enabled that objectification in her film Christmas on Earth (1963), and how Cheryl Dunye uses film to explore her own identity as a black lesbian artist. At the same time, the essays reveal commonalities, in- cluding a tendency toward documentary rather than fiction and a commitment to nonhi- erarchical, collaborative production practices. The volume’s final essay focuses explicitly on teaching women’s experimental films, addressing logistical concerns (how to acquire the films and secure proper viewing spaces) and extending the range of the book by sug- gesting alternative films for classroom use. -

THE HERETICS 95 Min. NTSC, Color/ B/W, 2009, Original Music

THE HERETICS 95 min. NTSC, color/ Contact: Crescent Diamond, Producer B/W, 2009, (510) 604-1060, [email protected] uncovers the inside story of the Second Wave of For more information, to see a trailer and to view the Women’s Movement for the first time in a the digital archive of all 27 issues of HERESIES, feature film. Joan Braderman, director and visit THE HERETICS’ website: narrator, follows her dream of becoming a www.heresiesfilmproject.org filmmaker to New York City in 1971. By lucky chance, she joins a feminist art collective at the Writer, Producer, Director: Joan Braderman epicenter of the 1970’s art world in lower Manhattan. In this first person account, THE Producer: Crescent Diamond HERETICS charts the history of a feminist THE HERETICS was shot in 24p mini-dv video. collective from the inside out. Principal Cinematography: Lily Henderson The Heresies Collective published HERESIES; Editors: Kathy Schermerhorn & Scott Hancock A Feminist Publication on Art and Politics from 1977-1992. The group included: writers such as Original Score: June Millington & Lee Madeloni Lucy Lippard and Elizabeth Hess; architect, Art Design & Direction: Joan Braderman & Molly Susana Torre; Creative Director of the New York McLeod Times and Real Simple Magazines, Janet Digital Graphics & 3-D Animation: Froelich; Curator of Film at the Museum of the Molly McLeod, Sarah Clark & Jeff Striker American Indian, Elizabeth Weatherford and filmmaker, Su Friedrich; as well as such prolific Principal B/W NTC & 70’s photography: and renowned artists: Joan Snyder, Pat Steir, Ida Jerry Kearns and Mary Beth Edelson Applebroog, Miriam Schapiro, Cecilia Vicuna, May Stevens, Harmony Hammond, Emma Amos, LOCATIONS: Carboneras, Spain; Santa Fe, New Michelle Stuart, Joyce Kozloff, Mary Miss, Amy Mexico; Northampton, Massachusetts; Portland, Sillman and Mary Beth Edelson. -

TOGETHER, AGAIN Women’S Collaborative Art + Community

TOGETHER, AGAIN Women’s Collaborative Art + Community BY CAREY LOVELACE We are developing the ability to work collectively and politically rather than privately and personally. From these will be built the values of the new society. —Roxanne Dunbar 1 “Female Liberation as the Basis for Social Liberation,” 1970 Cheri Gaulke (Feminist Art Workers member) has developed a theory of performance: “One plus one equals three.” —KMC Minns 2 “Moving Out Part Two: The Artists Speak,” 1979 3 “All for one and one for all” was the cheer of the Little Rascals (including token female Darla). Our Gang movies, with their ragtag children-heroes, were filmed during the Depression. This was an age of the collective spirit, fostering the idea that common folk banding together could defeat powerful interests. (Après moi, Walmart!) Front Range, Front Range Women Artists, Boulder , CO, 1984 (Jerry R. West, Model). Photo courtesy of Meridel Rubinstein. The artists and groups in Making It Together: Women’s Collaborative Art and Community come from the 1970s, another era believing in communal potential. This exhibition covers a period stretching 4 roughly from 1969 through 1985, and those featured here engaged in social action—inspiringly, 1 In Robin Morgan, Sisterhood Is Powerful: An Anthology of Writings from the Women’s Liberation Movement (New York: Vintage Books, 1970), 492. 2 “Moving Out Part Two: The Artists Speak,” Spinning Off, May 1979. 3 Echoing the Three Muskateers. 4 As points of historical reference: NOW was formed in 1966, the first radical Women’s Liberation groups emerged in 1967. The 1970s saw a range of breakthroughs: In 1971, the Supreme Court decision Roe v. -

Express Night out | Arts & Events

Express Night Out | Arts & Events | Art Expansion: Joan Braderman on 'The Heretics' 11/2/09 2:47 PM Search: Local events newsletter 'Glee' Weezer Christian Siriano Dane Cook ARTS & EVENTS Post an Ad Jobs Cars Merchandise Top Stops Art Expansion: Joan Braderman on 'The Heretics' Rentals Homes Services What's going on tonight? Post This | Like (0) | Comments (0) ShareThis | Print Tickets Pets Personals Sound Bets Music with a local flavor Dine & Dash Comments (16) | Archive D.C. eats in quick bites Should MLB use replay to review all questionable calls? Life & Stuff Little stories we tell Yes Johnny Zeitgeist No Something to talk about Your Station: Select Your Station Baggage Check Ask Dr. Andrea Bonior advertisement http://www.expressnightout.com/content/2009/10/joan-braderman-american-university.php Page 1 of 3 Express Night Out | Arts & Events | Art Expansion: Joan Braderman on 'The Heretics' 11/2/09 2:47 PM Swengali Sports talk with attitude AWARD-WINNING VIDEO artist and writer Joan Braderman chronicles the feminist influence in art and life in her latest film, "The Heretics," an insider's look into the New York artists' collective that produced "Heresies: A Feminist Publication on Art and Politics" in the mid-1970s. Beginning with Braderman's transition from aspiring filmmaker to collective co-founder, the film tracks the group's response to the transformative social changes brought about by the civil rights movement and second-wave feminism. A Washington, D.C., native, Braderman is currently a professor of media arts at Hampshire College in Amherst, Mass. She will appear Friday at American University's Katzen Arts Center to show and discuss the film. -

Women Make Movies

Women Make Movies 2015/16 Catalog NEW RELEASES CLOSING NIGHT DOCUMENTARY COMPETITION CLOSING NIGHT GALA FUSION CENTERPIECE WOMEN OF THE WORLD SEATTLE INTERNATIONAL INSIDE OUT OUTFEST FESTIVAL (WOW) LONDON FILM FESTIVAL FILM FESTIVAL TORONTO LOS ANGELES LGBT FILM FESTIVAL Alice Walker: Beauty in Truth A film by Pratibha Parmar US, 2013 | 84 min | Sale $395 | Rental $150 | # L15116 3 ALICE WALKER: BEAUTY IN TRUTH tells the compelling story of an extraordinary woman. Alice Walker made history as the first black woman to win the Pulitzer Prize for fiction for her ground- breaking novel, The Color Purple. Her early life unfolded in the midst of violent racism and poverty during some of the most turbulent years of profound social and political changes in North American history during the Civil Rights Movement. Mixing powerful archival footage with moving testimoni- als from friends and colleagues such as Howard Zinn, Angela Y. Davis, Gloria Steinem, Beverly “An intimate, exquisitely Guy-Sheftall, Quincy Jones, Steven Spielberg and rendered portrait of one of Danny Glover, ALICE WALKER: BEAUTY IN TRUTH the great artists of our time.” offers audiences a penetrating look at the life Ava DuVernay, Filmmaker & Founder of AAFRM and art of an artist, intellectual, self-confessed renegade and human rights activist. “Parmar’s powerful new film… masterfully presents Alice Walker’s revolutionary story as • Napa Valley Film Festival, Jury Prize for Best Documentary integral to American history.” • Qfest Philadelphia, Jury Prize for Best Documentary Heidi Hutner, Prof. of English & • QReel, Audience Award for Best Documentary Dir. of Environmental Humanities • African Diaspora Int’l Film Festival, Public Award for Best Film Directed by a Woman of Color Program, Stonybrook Univ. -

Contact: Crescent Diamond, Producer (510) 604-1060, [email protected]

Contact: Crescent Diamond, Producer (510) 604-1060, [email protected] http://www.heresiesfilmproject.org FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE - August, 2009, NYC. World Premiere of award-winning documentary, THE HERETICS opens October 9th, 2009 at New York MoMA for six-night run. The World Premiere of the award-winning documentary feature, THE HERETICS, written and directed by Joan Braderman and produced by Crescent Diamond. Opens Friday, October 9th, 2009 at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. The feature film runs 95 minutes and will be shown Friday, October 9, 7:00; Saturday, October 10, 7:30; Sunday, October 11, 2:00; Monday, October 12, 4:00; Wednesday, October 14, 4:00; Thursday, October 15, 7:00. Tickets can be purchased at the box office. MoMA, 11 West 53 St. New York, NY 10019 (212) 708-9400. Organized by Sally Berger, Assistant Curator, Department of Film. THE HERETICS uncovers the inside story of the Second Wave of the Women’s Movement for the first time in a feature film. Joan Braderman, director and narrator, follows her dream of becoming a filmmaker to New York City in 1971. By lucky chance, she joins a feminist art collective at the epicenter of the 1970’s art world in lower Manhattan. In this first person account, THE HERETICS charts the history of a feminist collective from the inside out. The Heresies Collective published HERESIES; A Feminist Publication on Art and Politics from 1977- 1992. The group included: writers such as Lucy Lippard and Elizabeth Hess; architect, Susana Torre; Creative Director of the New York Times and Real Simple Magazines, Janet Froelich; Curator of Film at the Museum of the American Indian, Elizabeth Weatherford and filmmaker, Su Friedrich; as well as such prolific and renown artists: Joan Snyder, Pat Steir, Ida Applebroog, Miriam Schapiro, Cecilia Vicuna, May Stevens, Harmony Hammond, Emma Amos, Michelle Stuart, Joyce Kozloff, Mary Miss, Amy Sillman and Marybeth Edelson. -

Joan Braderman Filmography

• FILMS BY whips them off and dishes the dirt: movies meet life, JOAN BRADERMAN • life meets death and romance meets Perdue chicken in this meditation on our illicit VCR pleasures. Watch and eat your heart out. “ PARA NO OLVIDAR (6 min, 2004) a digital video --- B. Ruby Rich, culture critic, author, Chick Flicks collaging images of the streets of Old Havana for use on the website and in the permanent exhibition Selected Shows & Awards of The Office of the Historian of the City of Havana. • Premiere: Video Visions, NY Film Festival, Lincoln Center, 1993 • Europe: British Film Theater, London, 1993 Wexner Center for the Arts, Ohio Bodies in Crisis, Oct. 1993 -Chicago Filmmakers Institute of Contemporary Art - Boston San Francisco International Lesbian & Gay Film/ VIDEO BITES; TRIPTYCH FOR THE TURN OF Video Festival THE CENTURY (1998-1999) Black Maria Film/Video Festival, *Juror's Citation 24 min., D, sound, color Award* Part I – Blow; Part II – Framed Atlanta Film/Video Festival Award, *Best Dramatic Part III – The Flight of Global Capital Criticism* Co-Directed by Dana Master Women in the Director's Chair Festival, Chicago; International House, Our Dinner with Joan, Selected Shows & Awards Philadelphia Independent MassMedia Festival, Zone Art Center, • Premiere: PANDEMONIUM FESTIVAL FOR Springfield, Mass MOVING IMAGES, October 23, 1999, Lux Center, Cicade de Vigo International Festival de Video, London, #2, Audience Choice Award Vigo, Spain Moscow Television Impakt Festival, The Netherlands The American Center, Paris Harvard University, -

Su Friedrich

SU FRIEDRICH 106 Van Buren Street Brooklyn, New York 11221 (718) 599-7601 land, (917) 620-6765 cell [email protected] www.sufriedrich.com ═════════════════════════════════════════════════════════════ FILMOGRAPHY and VIDEOGRAPHY: I Cannot Tell You How I Feel 2016 42 min. video color sound Queen Takes Pawn 2013 6.5 min. video color sound Gut Renovation 2012 81min. video color sound Practice Makes Perfect 2012 11min. video color sound Funkytown 2011 1 min. video color sound Conservation 101 2010 6 min. video color sound From the Ground Up 2008 54 min. video color sound Seeing Red 2005 27 min. video color sound The Head of a Pin 2004 21 min. video color sound The Odds of Recovery 2002 65 min. 16mm color sound Being Cecilia 1999 3 min. video color sound Hide and Seek 1996 65 min. 16mm b&w sound Rules of the Road 1993 31 min. 16mm color sound Lesbian Avengers Eat Fire, Too 1994 60 min. video color sound First Comes Love 1991 22 min. 16mm b&w sound Sink or Swim 1990 48 min. 16mm b&w sound Damned If You Don’t 1987 42 min. 16mm b&w sound The Ties That Bind 1984 55 min. 16mm b&w sound But No One 1982 9 min. 16mm b&w silent Gently Down the Stream 1981 14 min. 16mm b&w silent I Suggest Mine 1980 6 min. 16mm bw&col silent Scar Tissue 1979 6 min. 16mm b&w silent Cool Hands, Warm Heart 1979 16 min. 16mm b&w silent Hot Water 1978 12 min. s-8 b&w sound GRANTS AND AWARDS: 2015 Sink or Swim was one of the 25 films chosen by the Library of Congress to be included in the National Film Registry 2012 Princeton University Committee on Research in the Humanities