Language & the Moving Image

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Artist's Voice Since 1981 Bombsite

THE ARTIST’S VOICE SINCE 1981 BOMBSITE Peter Campus by John Hanhardt BOMB 68/Summer 1999, ART Peter Campus. Shadow Projection, 1974, video installation. Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery. My visit with Peter Campus was partially motivated by my desire to see his new work, a set of videotapes entitled Video Ergo Sum that includes Dreams, Steps and Karneval und Jude. These new works proved to be an extraordinary extension of Peter’s earlier engagement with video and marked his renewed commitment to the medium. Along with Vito Acconci, Dara Birnbaum, Gary Hill, Joan Jonas, Bruce Nauman, Nam June Paik, Steina and Woody Vasulka, and Bill Viola, Peter is one of the central artists in the history of the transformation of video into an art form. He holds a distinctive place in contemporary American art through a body of work distinguished by its articulation of a sophisticated poetics of image making dialectically linked to an incisive and subtle exploration of the properties of different media—videotape, video installations, photography, photographic slide installations and digital photography. The video installations and videotapes he created between 1971 and 1978 considered the fashioning of the self through the artist’s and spectator’s relationship to image making. Campus’s investigations into the apparatus of the video system and the relationship of the 1 of 16 camera to the space it occupied were elaborated in a series of installations. In mem [1975], the artist turned the camera onto the body of the specator and then projected the resulting image at an angle onto the gallery wall. -

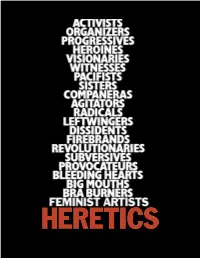

Heretics Proposal.Pdf

A New Feature Film Directed by Joan Braderman Produced by Crescent Diamond OVERVIEW ry in the first person because, in 1975, when we started meeting, I was one of 21 women who THE HERETICS is a feature-length experimental founded it. We did worldwide outreach through documentary film about the Women’s Art Move- the developing channels of the Women’s Move- ment of the 70’s in the USA, specifically, at the ment, commissioning new art and writing by center of the art world at that time, New York women from Chile to Australia. City. We began production in August of 2006 and expect to finish shooting by the end of June One of the three youngest women in the earliest 2007. The finish date is projected for June incarnation of the HERESIES collective, I remem- 2008. ber the tremendous admiration I had for these accomplished women who gathered every week The Women’s Movement is one of the largest in each others’ lofts and apartments. While the political movement in US history. Why then, founding collective oversaw the journal’s mis- are there still so few strong independent films sion and sustained it financially, a series of rela- about the many specific ways it worked? Why tively autonomous collectives of women created are there so few movies of what the world felt every aspect of each individual themed issue. As like to feminists when the Movement was going a result, hundreds of women were part of the strong? In order to represent both that history HERESIES project. We all learned how to do lay- and that charged emotional experience, we out, paste-ups and mechanicals, assembling the are making a film that will focus on one group magazines on the floors and walls of members’ in one segment of the larger living spaces. -

Press Release

Contact: Mark Linga 617.452.3586 [email protected] N E W S R E L E A S E The Media Test Wall Presents Video Trajectories (Redux): Selections from the MIT List Visual Arts Center New Media Collection featuring works by Bruce Nauman, Dara Birnbaum, Bill Viola, Nam June Paik and Gary Hill Viewing Hours: Daily 24 Hours Cambridge, MA – September 2008. The MIT List Visual Arts Center’s Media Test Wall presents Video Trajectories (Redux): Selections from the MIT List Visual Arts Center New Media Collection. This five-part exhibition series features selections from the List Center’s exhibition Video Trajectories (October 12-December 30, 2007) which was originally organized by MIT Professor Caroline A. Jones. The five selections in Video Trajectories (Redux), considered masterworks from video art history were acquired to become part of the MIT List Center’s New Media Collection. This exhibition re-introduces these works to a broader public: September 12-October 10 Bruce Nauman Slow Angle Walk (Beckett Walk), 1968 Video, black-and-white, sound, 60 minutes © 2008 Bruce Nauman/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, NY For Bruce Nauman, the video camera is an indispensable studio tool and witness. Barely edited, a characteristic Nauman tape from the late '60s shows the artist laconically following some absurd set of directions for an extended amount of time within the vague purview of a video camera mounted at a seemingly random angle in relation to the action. Slow Angle Walk is a classic of the genre, reflecting the artist's interest in Irish playwright Samuel Beckett, whose characters announce, "Let's go!" while the stage directions read, "No one moves." October 13-November 14 Dara Birnbaum Technology/Transformation: Wonder Woman, 1978-79 Video, color, sound, 5 minutes 50 seconds Courtesy of Electronic Arts Intermix Trained in architecture and painting, Birnbaum early on understood the estranging power of repetition. -

New Digital Art Space Revealed in the Santa Fe Railyard Art Vault at the Thoma Foundation Opens April 30 •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• •

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: April 21, 2021 Media Contact: Nicole Danti [email protected] New Digital Art Space Revealed in the Santa Fe Railyard Art Vault at the Thoma Foundation opens April 30 •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• • Santa Fe, New Mexico: The Carl & Marilynn Thoma Foundation announces the opening of a new 3,500 square-foot space for experiencing contemporary art in the Santa Fe Railyard District. Art Vault is dedicated to sharing the Foundation’s world-class collection of digital, electronic, virtual, and new media artworks, curated in thematic exhibitions. Art Vault at 540 South Guadalupe Street is the only digital art collection open to the public in the Southwest, and one of very few in the United States. Artworks from the Thoma Foundation collection are on view year-round, rotating seasonally. There is no admission fee, and school and group tours are available by appointment. Featured exhibitions will include emerging and mid-career artists alongside internationally renowned pioneers of video sculpture, self-taught computer artists, and influential digital time- based media artists. Large-scale digital and video installations invite viewers to broaden their understanding of technology with innovative perspectives on the human experience. Art Vault will take the place of The Thoma Foundation’s Art House, at 231 Delgado Street in Santa Fe, which will transition to the Foundation’s main office location. Founder Carl Thoma’s vision to bring larger, more accessible works of digital and media art to the international art hub of Santa Fe has been realized. “We are thrilled to increase our cultural contribution to the vibrant visual arts scene in Santa Fe. -

We Let the Quiet out from Below Its Curtain

Seattle City Council Public Safety, Government Relations, and Arts Committee Meeting Tuesday, 2:00 PM, August 15, 2006 Words’ Worth The Poetry Program of the Seattle City Council Curated by Jeannette Allée Today’s poet is Gary Hill Gary Hill was born in Santa Monica, CA and currently lives in Seattle. Originally a sculptor, Hill began working with sound, text, and video in the early 1970’s and has produced a large body of both single-channel video works and mixed-media installations. His video, installation and performance work has been presented at museums and institutions throughout the world, including solo exhibitions at the Musée national d'art moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris; Guggenheim Museum SoHo, NY; Museum für Gegenwartskunst, Öffentliche Kunstsammlung, Basel; Museu d’Art Contemporani, Barcelona; and Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg, among others. Hill has received fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Rockefeller and Guggenheim Foundations, and has been the recipient of numerous awards and honors, most notably the Leone d’Oro Prize for Sculpture at the Venice Biennale in 1995 and a John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation “Genuis” Grant in 1998. Site Recite (a prologue) by Gary Hill Nothing seems to have ever been moved. There is something of every description which can only be a trap. Maybe it all moves proportionately cancelling out change and the estrangement of judgement. No, an other order pervades. It's happening all at once, I'm just a disturbance wrapped up in myself, a kind of ghost vampirically passing through the forest passing through the trees. -

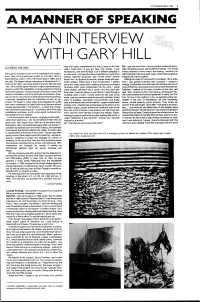

A Manner of Speaking : an Interview with Gary Hill

AFTERIMAGE/March 1983 9 A MANNER OF SPEAKING AN INTERVIEW WITH GARY HILL thing that really overwhelmed me was a show at the Met GH: I got into sound first. I discovered the sculptures gener- LUCINDA FURLONG called "1940-1970 ." It was the New York School. I was ated interesting sounds, lots of different timbres. The overall knocked out, and went through a lot of different attitudes in texture seemed to mirror what I was seeing. I worked a lot Although he is better known for his videotapes and installa- my own work. I still used the same materials, but I went from with loops and multi-trackaudio tapes, which later became an tions, Gary Hill has also been prolific as a sculptor. Born in making cage-like structures with human forms-almost integral part of the sculpture. Santa Monica, Calif. in 1951, Hill moved east in 1969, and in Bosch-like-to abstract biomorphic shapes mixed with geo- Getting into video isn't so smooth in retrospect. I think atthe the early '70s began making videotapes at Woodstock (N.Y.) metric shapes. Pretty soon it was all geometric. I started time I was getting frustrated with sculpture. I needed a Community Video. Like many artists in the late '60s and early using wire mesh, spray paint, welding armatures for shaped change . I was drawn more and more into working with sound. 70s, Hill's earliest tapes reflected a highly experimental ap- canvases which were incorporated into the work. I would Around thattime, WoodstockCommunityVideo had been es- proach in which the capabilities of various electronic imaging make shapes, pile them into a corner, and then work with tablished. -

Ryan Trecartin: Data Purge

Ryan Trecartin: Data Purge by Jon Davies The young American artist Ryan Trecartin’s vertiginous performance, media and installation practice seeks to give physical form to the abstractions that govern life in the digital age. The structures and motifs of globalized, networked media and communications become characters, narratives and environments in his work. Cyberculture is rewired through the fallible human body, with all its entropic, expressive energies and potential for physical and communicative breakdown. The result is a messy and excessive sensory bombardment that scrambles his viewers’ processors and rewires their comprehension of cinematic storytelling, time and space. Consequently, Trecartin’s work has commanded the art world’s attention in a matter of a few short years. Trecartin was born in 1981 in Webster, Texas, and raised in rural Ohio. He attended the Rhode Island School of Design,1 where he studied video and animation, receiving his bfa in 2004. Relatively cheap to live Ryan Trecartin in, packed with art students and close (but not too close) to New York, P.opular S.ky (section ish), the city of Providence is known for being a hotbed of discipline-crossing 2009, Still from an diy experimentation in terms of culture and community. It was here that HD video. Courtesy the artist and Elizabeth Dee Trecartin found his crew of like-minded creators, dubbed the xppl (New York). (Experimental People Band). Upon graduation, Trecartin and friends 20 Screen Space SWITCH 21 Ryan Trecartin I-Be Area, 2007, Still from a video. Courtesy the artist and Elizabeth Dee (New York). Trecartin’s characters are digital data and they know it. -

Gary Hill | Toward Common Cause

Gary Hill Gary Hill, SELF ( ), 2016, Mixed media. Courtesy bitforms gallery, New York. A narrow room in a gallery with an artwork installation. The gallery has white walls and concrete floors. The art installation included in the image comprises of three white acrylic units mounted to the wall. Each unit has a lens protruding out from the center. An electrical cord dangles from each and these are gathered along the wall to an outlet. Each of the units are in different geometric shapes – a square, triangle, and circle. Gary Hill was one of the first artists to use video technology to do something other than straight recording, and he continues to be an innovator today. During his forty-plus-year career, he has moved well beyond the narrow confines of video into experimental interactive technologies. All of his explorations of myriad novel electronic media, however diverse, are deployed as means to investigate the relationship between mind and body, perception and cognition, language and consciousness. Hill’s earliest work, made in the late 1960s, was metal sculpture. Fascinated more by the sounds the metal could produce than by its appearance, he began to extend his practice to electronic sound, sound synthesizers, video cameras, and eventually to interactive installations. He deconstructed his works as he made them, both literally and figuratively: literally, because we can see wires, cathode tubes, the guts of technology; and figuratively, because he relentlessly probes the tenuous and glitchy nature of the self. In a 2009 interview, Hill said that, in retrospect, he was surprised how often his use of the video camera has nothing to do with looking through the eyepiece. -

Video Installation, Gary Hill: Tall Ships Opens Sept. 26 in the University Art Gallery at UCSD

Video installation, Gary Hill: Tall ships opens Sept. 26 in the University Art Gallery at UCSD September 8, 1997 Media Contact: Kathleen Stoughton, University Art Gallery, (619) 534-0419, or [email protected], or Jan Jennings, (619) 822-1684, or jnjenningsgucsd.edu VIDEO INSTALLATION, GARY HILL: TALL SHIPS OPENS SEPT. 26 IN THE UNIVERSITY ART GALLERY AT UCSD Gary Hill: Tall Ships, an interactive projective video installation, will be on view Sept. 26 through Dec. 13 in the University Art Gallery at the University of California, San Diego. A reception for the artist, open to the public, will be held from 7 to 9 p.m. Sept. 25. The installation consists of a 60-foot long corridor which is completely dark. The movement of a viewer through the corridor triggers the emergence of projected images of people of varying ages, gender and ethnic origin on the walls of the corridor. The light from the projected videos provides a minimal light in the installation space and creates silhouettes of other viewers in the space. "You begin to see the shapes and shadows and light cast by the figures onto people's faces," says Hill. "It's very subtle, but the viewers begin to mix with the projections." For Hill, the choreography of dark space, visions, and silence creates a meditative space for the viewer to interact with the images (both video and reap to connect with them or to feel isolated. Hill's idea is to compel the viewer to explore his or her responses to others. Hill says the title for the installation was inspired by an old photograph taken in Seattle around 1930 of a tall ship: "I associated those huge masts and full sails with people standing...the thought of that kind of ship on the high seas that frontal view of extreme verticality coming towards you. -

Resisting the Logic of Late Capitalism in the Digital Age

Performative identity in networked spaces: Resisting the logic of late capitalism in the digital age Kerry Doran General Honors Thesis Professor Claire Farago – Thesis Advisor Art History Professor Fred Anderson – General Honors Council Representative Honors Program, History Professor Robert Nauman – Art History Honors Council Representative Art History Professor Mark Amerika – Committee Member Studio Arts Professor Karen S. Jacobs – Committee Member English University of Colorado Boulder April 4, 2012 CONTENTS Abstract Acknowledgements Preface I. Postmodernism, late capitalism, and schizophrenia Jean Baudrillard Frederic Jameson Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari II. The Multifariously Paradoxical Culture Industry The Situationist International, dérive, and détournement Situationist tactics today III. Facebook, or, the virtual embodiment of consumer capitalism Me, myself, and Facebook Why some people “Like” Facebook Capitalism 101: Objectification, alienation, and the fetishism of commodities Every detail counts. “Facebook helps you connect and share with the people in your life” My real (fake) Facebook A note on following pieces IV. Performative identity in networked spaces “Hey! My name’s Ryan! I’m a video kid. Digital.” Editing, fictionalizing, and performing the self Schizophrenic conceptual personae Conclusion: A postmodernism of resistance, or something else? 2 ABSTRACT The technological developments of the twenty-first century, most significantly the commercialization and widespread use of the Internet and its interactive technologies, -

216631157.Pdf

The Alternative Media Handbook ‘Alternative media’ are media produced by the socially, culturally and politically e xcluded: they are always independently run and often community-focused, ranging from pirate radio to activist publications, from digital video experiments to ra dical work on the Web. The Alternative Media Handbook explores the many and dive rse media forms that these non-mainstream media take. The Alternative Media Hand book gives brief histories of alternative radio, video and lm, press and activity on the Web, then offers an overview of global alternative media work through nu merous case studies, before moving on to provide practical information about alt ernative media production and how to get involved in it. The Alternative Media H andbook includes both theoretical and practical approaches and information, incl uding sections on: • • • • • • • • successful fundraising podcasting blogging publishing pitch g a project radio production culture jamming access to broadcasting. Kate Coyer is an independent radio producer, media activist and post-doctoral re search fellow with the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of P ennsylvania and Central European University in Budapest. Tony Dowmunt has been i nvolved in alternative video and television production since 1975 and is now cou rse tutor on the MA in Screen Documentary at Goldsmiths, University of London. A lan Fountain is currently Chief Executive of European Audiovisual Entrepreneurs (EAVE), a professional development programme for lm and television producers. He was the rst Commissioning Editor for Independent Film and TV at Channel Four, 198 1–94. Media Practice Edited by James Curran, Goldsmiths, University of London The Media Practice hand books are comprehensive resource books for students of media and journalism, and for anyone planning a career as a media professional. -

WHITNEY BIENNIAL 2006: DAY for NIGHT to OPEN Signature Survey Measuring the Mood of Contemporary American Art, March 2-May 28, 2006

Press Release Contact: Jan Rothschild, Stephen Soba, Meghan Bullock (212) 570-3633 or [email protected] www.whitney.org/press February 2006 WHITNEY BIENNIAL 2006: DAY FOR NIGHT TO OPEN Signature survey measuring the mood of contemporary American art, March 2-May 28, 2006 Peter Doig, Day for Night, 2005. Private Collection; courtesy Contemporary Fine Arts, Berlin. The curators have announced their selection of artists for the 2006 Whitney Biennial, which opens to the public on March 2, and remains on view at the Whitney Museum of American Art through May 28, 2006. The list of participating artists appears at the end of this release. Whitney Biennial 2006: Day for Night is curated by Chrissie Iles, the Whitney’s Anne & Joel Ehrenkranz Curator, and Philippe Vergne, the Deputy Director and Chief Curator of the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis. The Biennial’s lead sponsor is Altria. "Altria Group, Inc. is proud to continue its forty year relationship with the Whitney Museum of American Art by sponsoring the 2006 Biennial exhibition," remarked Jennifer P. Goodale, Vice President, Contributions, Altria Corporate Services, Inc. "This signature exhibition of some of the most bold and inspired work coming from artists' studios reflects our company's philosophy of supporting innovation, creativity and diversity in the arts." Whitney Biennial 2006: Day for Night takes its title from the 1973 François Truffaut film, whose original French name, La Nuit américaine, denotes the cinematic technique of shooting night scenes artificially during the day, using a special filter. This is the first Whitney Biennial to have a title attached to it.