Oral History Interview with Lucy Lippard, 2011 Mar. 15

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Archived News

Archived News 2007-2008 News articles from 2007-2008 Table of Contents Alumnae Cited for Accomplishments and Sage Salzer ’96................................................. 17 Service................................................................. 5 Porochista Khakpour ’00.................................. 18 Laura Hercher, Human Genetics Faculty............ 7 Marylou Berg ’92 ............................................. 18 Lorayne Carbon, Director of the Early Childhood Meema Spadola ’92.......................................... 18 Center.................................................................. 7 Warren Green ................................................... 18 Hunter Kaczorowski ’07..................................... 7 Debra Winger ................................................... 19 Sara Rudner, Director of the Graduate Program in Dance .............................................................. 7 Melvin Bukiet, Writing Faculty ....................... 19 Rahm Emanuel ’81 ............................................. 8 Anita Brown, Music Faculty ............................ 19 Mikal Shapiro...................................................... 8 Sara Rudner, Dance Faculty ............................. 19 Joan Gill Blank ’49 ............................................. 8 Victoria Hofmo ’81 .......................................... 20 Wayne Sanders, Voice Faculty........................... 8 Students Arrive on Campus.............................. 21 Desi Shelton-Seck MFA ’04............................... 9 Norman -

VIDEO" Nov 6 Sun 8 :00 PM GREY HAIRS + REAL SEVEN Nov 27 Sun 8 :00 PM DAVE OLIVE "RUNNING" Mr

Nov 5 Sat 2 :30 PM WILLIAM WEGMAN Nov 26 Sat 2 :30 PM "SHORT STORY VIDEO" Nov 6 Sun 8 :00 PM GREY HAIRS + REAL SEVEN Nov 27 Sun 8 :00 PM DAVE OLIVE "RUNNING" Mr . Wegman appeared on the Tonite Show last summer . Now he works at home in his Dave Olive lives in North Liberty, Iowa, own color studio . He will be premiering where he teaches elementary school . videotapes produced at his color studio and at WGBH Boston . JOE DEA "Short Stories" Nov 12 Sat 2 :30 PM KIT FITZGERALD Nov 13 Sun 8 :00 PM JOHN SANBORN Mr . Dea is a cartoonist who works in video . N r "EXCHANGE IN THREE PARTS" He lives in Hartford, Connecticut . recently completed at TV Laboratory at WNET 8 Channel 13 and currently showing in the tenth Dec 3 Sat 2 :30 PM JUAN DOWNEY 2W Bienale du Paris . Dec 4 Sun 8 :00 PM "MORE THAN TWO" QQ An experience in audio video stereo perception cc ~ Kit ON Z Fitzgerald and John Sanborn have been artist and an account of a video expedition to a OY in residence at ZBS Media and the TV Lab of WNET primitive tribe in South America : The Yanomany . cc cc Y Channel 13 and are currently involved in the o 0.0 Cn >- s International TV Workshop . Their work will be ]sec 10 Sat 2 :30 PM MARILYN GOLDSTEIN 9 W3(L W V O broadcast this season over Public TV . "Voice of the Handicapped" 0 W "Video Beats Westway" a 0 HZ a a OW Nov 19 Sat 2 :30 PM STEINA a W= W Nov 20 Sun 8 :00 PM "Snowed-in Tape and Other Work - 1977" Dec 11 Sun 8 :00 PM LYNDA BENGLIS / STANTON KAYE a 0 "How's Tricks?" Z c 0>NH . -

A Finding Aid to the Perls Galleries Records, 1937-1997, in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the Perls Galleries Records, 1937-1997, in the Archives of American Art Julie Schweitzer January 15, 2009 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Historical Note.................................................................................................................. 2 Scope and Content Note................................................................................................. 3 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Correspondence, 1937-1995.................................................................... 5 Series 2: Negatives, circa 1937-1995.................................................................. 100 Series 3: Photographs, circa 1937-1995.............................................................. 142 Series 4: Exhibition, Loan, and Sales Records, 1937-1995................................ -

Regionallst PAINTING and AMERICAN STUDIES Regionalism

REGiONALlST PAINTING AND AMERICAN STUDIES KENNETH J. LABUDDE Regionalism in American painting brings to mind immediately the period of the 1930's when the Middlewesterners JohnSteuart Curry, Grant Wood and Thomas Hart Benton enjoyed great reputation as the_ painters of Ameri can art. Curry, the Kansan; Benton, the Missourian; and Wood, the Iowan, each wandered off to New York, to Paris, to the great world of art, but each came home again to Kansas City, Cedar Rapids and Madison, Wisconsin. Only one of the three, Benton, is still living. At the recent dedication of his "Independence and the Opening of the West" in the Truman Library the ar tist declared it was his last big work, for scaffold painting takes too great a toll on a man now 72. Upon this occasion he enjoyed the acclaim of those gathered, but as a shrewdly intelligent, even intellectual man, he may have reflected that Wood and Curry, both dead foi* close to twenty years now, are slipping into obscur ity except in the region of the United States which they celebrated. Collec tors, whether institutional or private, who have the means and the interests to be a part of the great world have gone on to other painters. There are those who will say so much the worse for them, but I am content not to dwell on that issue but to speculate instead about art in our culture and the uses of art in cultural studies. I will explain that I am not convinced by those who hold with the conspir acy theory of art history, whether it be a Thomas Craven of yesterday or a John Canaday of today. -

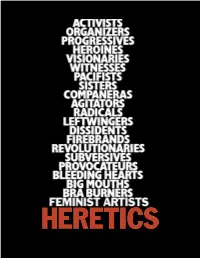

Heretics Proposal.Pdf

A New Feature Film Directed by Joan Braderman Produced by Crescent Diamond OVERVIEW ry in the first person because, in 1975, when we started meeting, I was one of 21 women who THE HERETICS is a feature-length experimental founded it. We did worldwide outreach through documentary film about the Women’s Art Move- the developing channels of the Women’s Move- ment of the 70’s in the USA, specifically, at the ment, commissioning new art and writing by center of the art world at that time, New York women from Chile to Australia. City. We began production in August of 2006 and expect to finish shooting by the end of June One of the three youngest women in the earliest 2007. The finish date is projected for June incarnation of the HERESIES collective, I remem- 2008. ber the tremendous admiration I had for these accomplished women who gathered every week The Women’s Movement is one of the largest in each others’ lofts and apartments. While the political movement in US history. Why then, founding collective oversaw the journal’s mis- are there still so few strong independent films sion and sustained it financially, a series of rela- about the many specific ways it worked? Why tively autonomous collectives of women created are there so few movies of what the world felt every aspect of each individual themed issue. As like to feminists when the Movement was going a result, hundreds of women were part of the strong? In order to represent both that history HERESIES project. We all learned how to do lay- and that charged emotional experience, we out, paste-ups and mechanicals, assembling the are making a film that will focus on one group magazines on the floors and walls of members’ in one segment of the larger living spaces. -

Feminist Art, the Women's Movement, and History

Working Women’s Menu, Women in Their Workplaces Conference, Los Angeles, CA. Pictured l to r: Anne Mavor, Jerri Allyn, Chutney Gunderson, Arlene Raven; photo credit: The Waitresses 70 THE WAITRESSES UNPEELED In the Name of Love: Feminist Art, the Women’s Movement and History By Michelle Moravec This linking of past and future, through the mediation of an artist/historian striving for change in the name of love, is one sort of “radical limit” for history. 1 The above quote comes from an exchange between the documentary videomaker, film producer, and professor Alexandra Juhasz and the critic Antoinette Burton. This incredibly poignant article, itself a collaboration in the form of a conversation about the idea of women’s collaborative art, neatly joins the strands I want to braid together in this piece about The Waitresses. Juhasz and Burton’s conversation is at once a meditation of the function of political art, the role of history in documenting, sustaining and perhaps transforming those movements, and the influence gender has on these constructions. Both women are acutely aware of the limitations of a socially engaged history, particularly one that seeks to create change both in the writing of history, but also in society itself. In the case of Juhasz’s work on communities around AIDS, the limitation she references in the above quote is that the movement cannot forestall the inevitable death of many of its members. In this piece, I want to explore the “radical limit” that exists within the historiography of the women’s movement, although in its case it is a moribund narrative that threatens to trap the women’s movement, fixed forever like an insect under amber. -

Studio International Magazine: Tales from Peter Townsend’S Editorial Papers 1965-1975

Studio International magazine: Tales from Peter Townsend’s editorial papers 1965-1975 Joanna Melvin 49015858 2013 Declaration of authorship I, Joanna Melvin certify that the worK presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this is indicated in the thesis. i Tales from Studio International Magazine: Peter Townsend’s editorial papers, 1965-1975 When Peter Townsend was appointed editor of Studio International in November 1965 it was the longest running British art magazine, founded 1893 as The Studio by Charles Holme with editor Gleeson White. Townsend’s predecessor, GS Whittet adopted the additional International in 1964, devised to stimulate advertising. The change facilitated Townsend’s reinvention of the radical policies of its founder as a magazine for artists with an international outlooK. His decision to appoint an International Advisory Committee as well as a London based Advisory Board show this commitment. Townsend’s editorial in January 1966 declares the magazine’s aim, ‘not to ape’ its ancestor, but ‘rediscover its liveliness.’ He emphasised magazine’s geographical position, poised between Europe and the US, susceptible to the influences of both and wholly committed to neither, it would be alert to what the artists themselves wanted. Townsend’s policy pioneered the magazine’s presentation of new experimental practices and art-for-the-page as well as the magazine as an alternative exhibition site and specially designed artist’s covers. The thesis gives centre stage to a British perspective on international and transatlantic dialogues from 1965-1975, presenting case studies to show the importance of the magazine’s influence achieved through Townsend’s policy of devolving responsibility to artists and Key assistant editors, Charles Harrison, John McEwen, and contributing editor Barbara Reise. -

Mapping Robert Storr

Mapping Robert Storr Author Storr, Robert Date 1994 Publisher The Museum of Modern Art: Distributed by H.N. Abrams ISBN 0870701215, 0810961407 Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/436 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history— from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art bk 99 £ 05?'^ £ t***>rij tuin .' tTTTTl.l-H7—1 gm*: \KN^ ( Ciji rsjn rr &n^ u *Trr» 4 ^ 4 figS w A £ MoMA Mapping Robert Storr THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK DISTRIBUTED BY HARRY N. ABRAMS, INC., NEW YORK (4 refuse Published in conjunction with the exhibition Mappingat The Museum of Modern Art, New York, October 6— tfoti h December 20, 1994, organized by Robert Storr, Curator, Department of Painting and Sculpture The exhibition is supported by AT&TNEW ART/NEW VISIONS. Additional funding is provided by the Contemporary Exhibition Fund of The Museum of Modern Art, established with gifts from Lily Auchincloss, Agnes Gund and Daniel Shapiro, and Mr. and Mrs. Ronald S. Lauder. This publication is supported in part by a grant from The Junior Associates of The Museum of Modern Art. Produced by the Department of Publications The Museum of Modern Art, New York Osa Brown, Director of Publications Edited by Alexandra Bonfante-Warren Designed by Jean Garrett Production by Marc Sapir Printed by Hull Printing Bound by Mueller Trade Bindery Copyright © 1994 by The Museum of Modern Art, New York Certain illustrations are covered by claims to copyright cited in the Photograph Credits. -

Is Marina Abramović the World's Best-Known Living Artist? She Might

Abrams, Amah-Rose. “Marina Abramovic: A Woman’s World.” Sotheby’s. May 10, 2021 Is Marina Abramović the world’s best-known living artist? She might well be. Starting out in the radical performance art scene in the early 1970s, Abramović went on to take the medium to the masses. Working with her collaborator and partner Ulay through the 1980s and beyond, she developed long durational performance art with a focus on the body, human connection and endurance. In The Lovers, 1998, she and Ulay met in the middle of the Great Wall of China and ended their relationship. For Balkan Baroque, 1997, she scrubbed clean a huge number of cow bones, winning the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale for her work. And in The Artist is Present 2010, performed at MoMA in New York, she sat for eight hours a day engaging in prolonged eye contact over three months – it was one of the most popular exhibits in the museum’s history. Since then, she has continued to raise the profile of artists around the world by founding the Marina Abramović Institute, her organisation aimed at expanding the accessibility of time- based work and creating new possibilities for collaboration among thinkers of all fields. MARINA ABRAMOVIĆ / ULAY, THE LOVERS, MARCH–JUNE 1988, A PERFORMANCE THAT TOOK PLACE ACROSS 90 DAYS ON THE GREAT WALL OF CHINA. © MARINA ABRAMOVIĆ AND ULAY, COURTESY: THE MARINA ABRAMOVIĆ ARCHIVES / DACS 2021. Fittingly for someone whose work has long engaged with issues around time, Marina Abramović has got her lockdown routine down. She works out, has a leisurely breakfast, works during the day and in the evening, she watches films. -

The Museum of Modern Art

The Museum of Modern Art For Immediate Release May 1995 ARTIST'S CHOICE: ELIZABETH MURRAY June 20 - August 22, 1995 An exhibition conceived and installed by American artist Elizabeth Murray is the fifth in The Museum of Modern Art's series of ARTIST'S CHOICE exhibitions. On view from June 20 to August 22, 1995, ARTIST'S CHOICE: ELIZABETH MURRAY presents more than 100 drawings, paintings, prints, and sculptures by approximately seventy women artists. The exhibition involves works created between 1914 and 1973, including those ranging from early modernists Frida Kahlo and Liubov Popova to contemporary artists Nancy Graves and Dorothea Rockburne. Murray focuses particular attention on artists who made their reputations during the 1950s and 1960s, such as Lee Bontecou, Agnes Martin, Joan Mitchell, when Murray herself was studying and forming her style. This exhibition and the accompanying video and panel discussion are made possible by a generous grant from The Charles A. Dana Foundation. Organized in collaboration with Kirk Varnedoe, Chief Curator, Department of Painting and Sculpture, the ARTIST'S CHOICE series invites artists to create an exhibition from the Museum's collection according to a personally chosen theme or principle. "I wanted, for myself, to explore what being a woman in the art world has meant," Murray writes in the exhibition brochure. "I wanted to weave together a sense of the genuine and profound contribution women's work has made to the art of our time." - more - 11 West 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019-5498 Tel: 212-708-9400 Fax: 212-708-9889 2 Installed in the Museum's third-floor contemporary painting and sculpture galleries, the exhibition is arranged in thematic groupings. -

One of a Kind, Unique Artist's Books Heide

ONE OF A KIND ONE OF A KIND Unique Artist’s Books curated by Heide Hatry Pierre Menard Gallery Cambridge, MA 2011 ConTenTS © 2011, Pierre Menard Gallery Foreword 10 Arrow Street, Cambridge, MA 02138 by John Wronoski 6 Paul* M. Kaestner 74 617 868 20033 / www.pierremenardgallery.com Kahn & Selesnick 78 Editing: Heide Hatry Curator’s Statement Ulrich Klieber 66 Design: Heide Hatry, Joanna Seitz by Heide Hatry 7 Bill Knott 82 All images © the artist Bodo Korsig 84 Foreword © 2011 John Wronoski The Artist’s Book: Rich Kostelanetz 88 Curator’s Statement © 2011 Heide Hatry A Matter of Self-Reflection Christina Kruse 90 The Artist’s Book: A Matter of Self-Reflection © 2011 Thyrza Nichols Goodeve by Thyrza Nichols Goodeve 8 Andrea Lange 92 All rights reserved Nick Lawrence 94 No part of this catalogue Jean-Jacques Lebel 96 may be reproduced in any form Roberta Allen 18 Gregg LeFevre 98 by electronic or mechanical means, including photocopying, recording, or information storage retrieval Tatjana Bergelt 20 Annette Lemieux 100 without permission in writing from the publisher Elena Berriolo 24 Stephen Lipman 102 Star Black 26 Larry Miller 104 Christine Bofinger 28 Kate Millett 108 Curator’s Acknowledgements Dianne Bowen 30 Roberta Paul 110 My deepest gratitude belongs to Pierre Menard Gallery, the most generous gallery I’ve ever worked with Ian Boyden 32 Jim Peters 112 Dove Bradshaw 36 Raquel Rabinovich 116 I want to acknowledge the writers who have contributed text for the artist’s books Eli Brown 38 Aviva Rahmani 118 Jorge Accame, Walter Abish, Samuel Beckett, Paul Celan, Max Frisch, Sam Hamill, Friedrich Hoelderin, John Keats, Robert Kelly Inge Bruggeman 40 Osmo Rauhala 120 Andreas Koziol, Stéphane Mallarmé, Herbert Niemann, Johann P. -

Weekly Schedule

ARTH 787: Seminar in Contemporary Art Feminist and Queer Art History, 1971-present Spring 2007 Professor Richard Meyer ([email protected]) Mondays, 2-4:50 p.m. Dept. of Art History, University of Pennsylvania Jaffe 201 Course Description and Requirements This seminar traces the development of a critical literature in feminist and gay/lesbian art history. Beginning with some foundational texts of the 1970s (Linda Nochlin’s "Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?,” James Saslow’s "Closets in the Museum: Homophobia and Art History"), we will examine how art historians, artists, critics, and curators have addressed issues of gender and sexuality over the course of the last three decades. The seminar approaches feminist and queer art history as distinct, if sometimes allied, fields of inquiry. Students will be asked to attend closely to the historical specificity of the texts and critical debates at issue in each case. Students are expected to complete all required reading prior to seminar meetings and to discuss the texts and critical issues at hand during each session. On a rotating basis, each student will prepare a 2-page response to an assigned text which will then be used to initiate discussion in seminar. Toward the end of the semester, students will deliver a 15-minute presentation on their seminar research to date. In consultation with both the professor and the other seminar members, each student will develop his or her oral presentation into a final paper of approximately 20 - 25 pages. Required Texts: For purchase at Penn Book Center: 1. Norma Broude and Mary Garrard, The Power of Feminist Art: The American Movement of the 1970s, History and Impact (New York: Harry N.